A seasoning, marinade and color source. Annatto is an essential condiment in southeastern Mexico’s kitchens, thanks to which we have two national gastronomical glories: cochinita pibil and tacos al pastor, among many other dishes.

In pre-Hispanic Mexico it was considered a sacred plant and was used mainly as a pigment. The process to obtain annatto paste by decan-ting the powder found in seeds is a highly refined mayan technique.

After the discovery of America it was taken to Europe where it was used to dye everything from leather, wool, silk and cotton, to cheese, butter and smoked fish. It grows in southern Mexico, especially in Yucatán and Campeche; although currently it is also grown in countries such as Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.

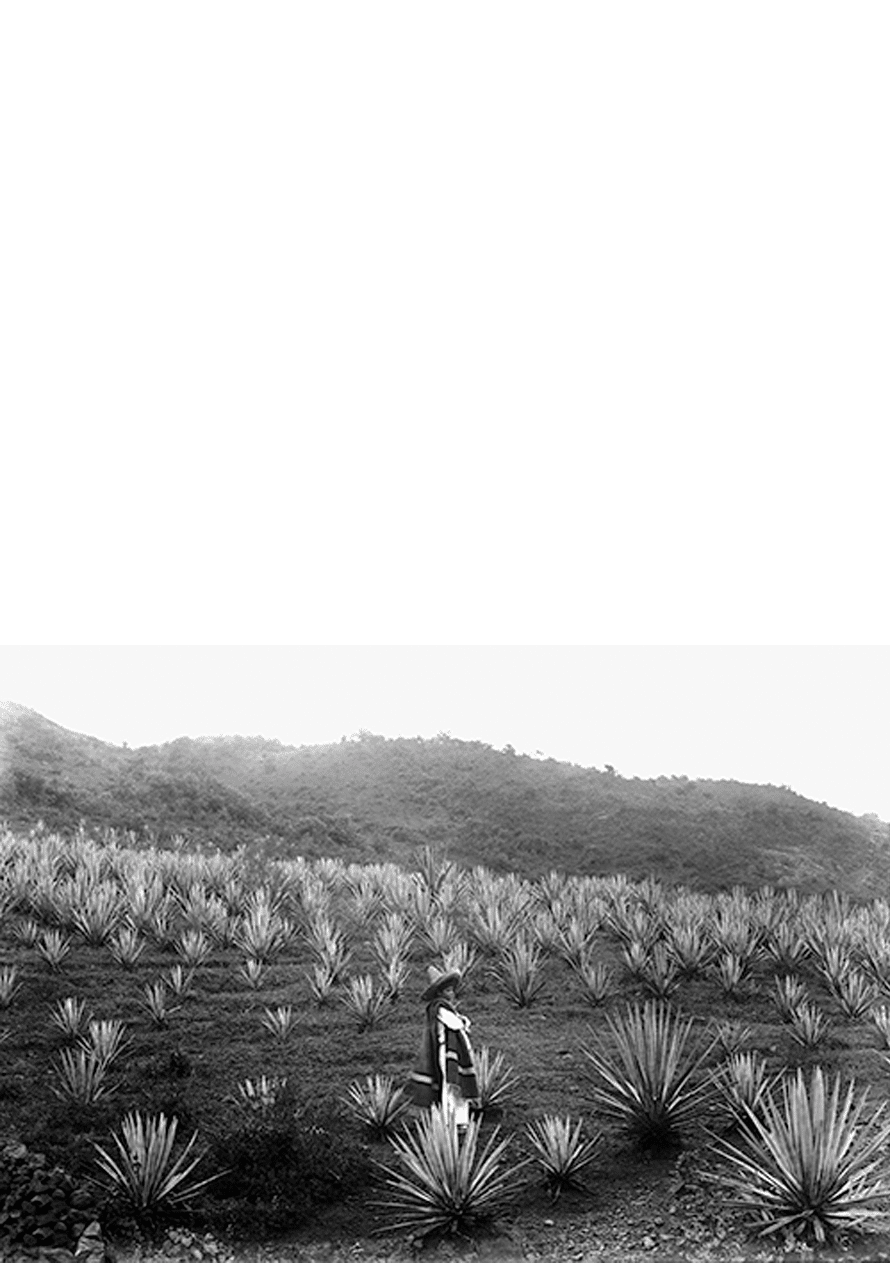

“There is a plant in this country that is both a tree and a thistle. Its leaves are thick as a knee and longer than an arm [...]. When mature, the indigenous people cut the base of the shoot, which produces a liqueur that they mix with the bark of a particular tree [...]. This tree is of the greatest use because it produces spirits, vinegar, honey and a concoction similar to the juice of a cooked grape”,1 this is how the Spaniards described maguey, a plant that attracted their attention when they arrived in the New World.

The indigenous people called it metl or mexcametl. When fermenting its mucilage they produced pulque, and took advantage of its fleshy leaves to extract a fiber with which they wove dresses, sandals and ropes, among other objects.

It was the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus who gave it the scientific name of Agave —which in Greek means “admirable”—, to name all plants of its genus. Of the over 285 varieties of agave that have been described in the world, 200 are found within Mexican territory. In addition to its importance for the production of the most representative drinks in the country, its cultivation helps stop soil erosion, its stem is used to build huts, and its roots are employed to make brushes and brooms.

Amongst Mexico’s gastronomic contributions to the world, avocado is the crown jewel. Its name comes from the Nahuatl word ahuacatl that means “tree testicles”. One of the first references about its consumption dates from 1519 and appears in the book Suma de geografía by Martín Fernández de Enciso: “Inside it is like butter, and of marvelous flavor, and leaving such a good and delicate taste that it is quite wonderful”.2

Mexico is the main supplier in the international market of this fruit of which flavor, texture and properties are so highly regarded that it is considered as “green gold”.

Its nutrients are also used in cosmetic formulas for the preparation of lotions, soaps, creams and hair products.

This microscopic blue-green algae was known in pre-Hispanic times as tecuitlat, which means “stone excrement”. Mexicas harvested it in the surroundings of Lake Texcoco to make a paste that the Spaniards named “earth cheese”.

Nowadays, it is known as a superfood because it provides a much more digestible protein intake than red meat, in addition to a large amount of vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, chlorophyll and a wide range of phytochemicals. It is one of the most appreciated food supplements in the world, chosen by NASA to enrich the diet of astronauts in space missions.

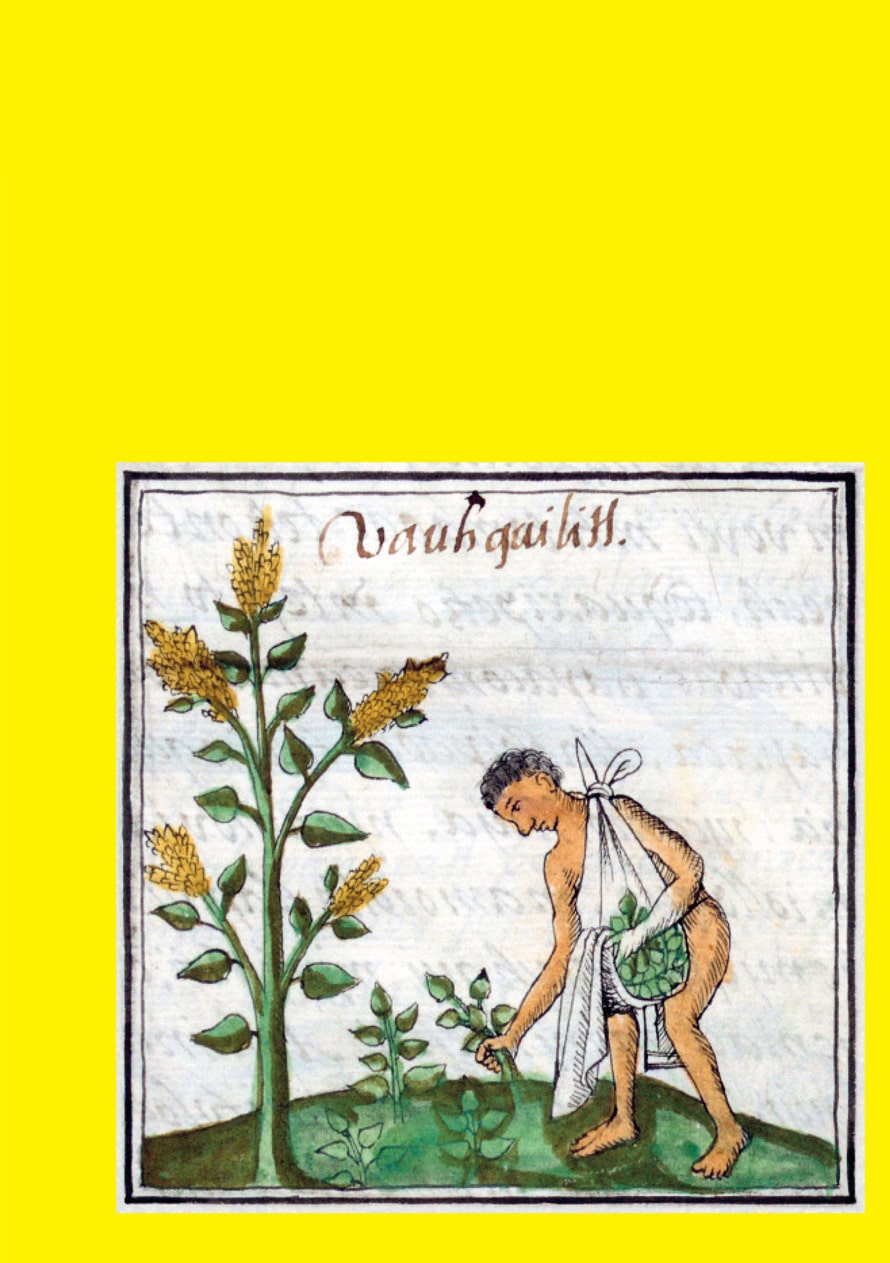

The four essential foods in the diet of ancient Mexicans were maize, beans, chili and amaranth. Aztecs considered amaranth as the food of gods. The ritual use of its seed gave body to the deities and its dust, like pinolli, was a fundamental provision that gave vitality to the mortal body of travelers.

Due to the strong link between amaranth and indigenous religious rituals, Christian missionaries almost eradicated its cultivation; fortunately, amaranth grew wild and its use continued. “Alegrías” —sweets made from amaranth and maguey honey— survived and have continued to nourish Mexican people to this day. At the end of the 20th century, the enormous nutritional value of amaranth was rediscovered, and it has even been suggested as a possible resource against world hunger.

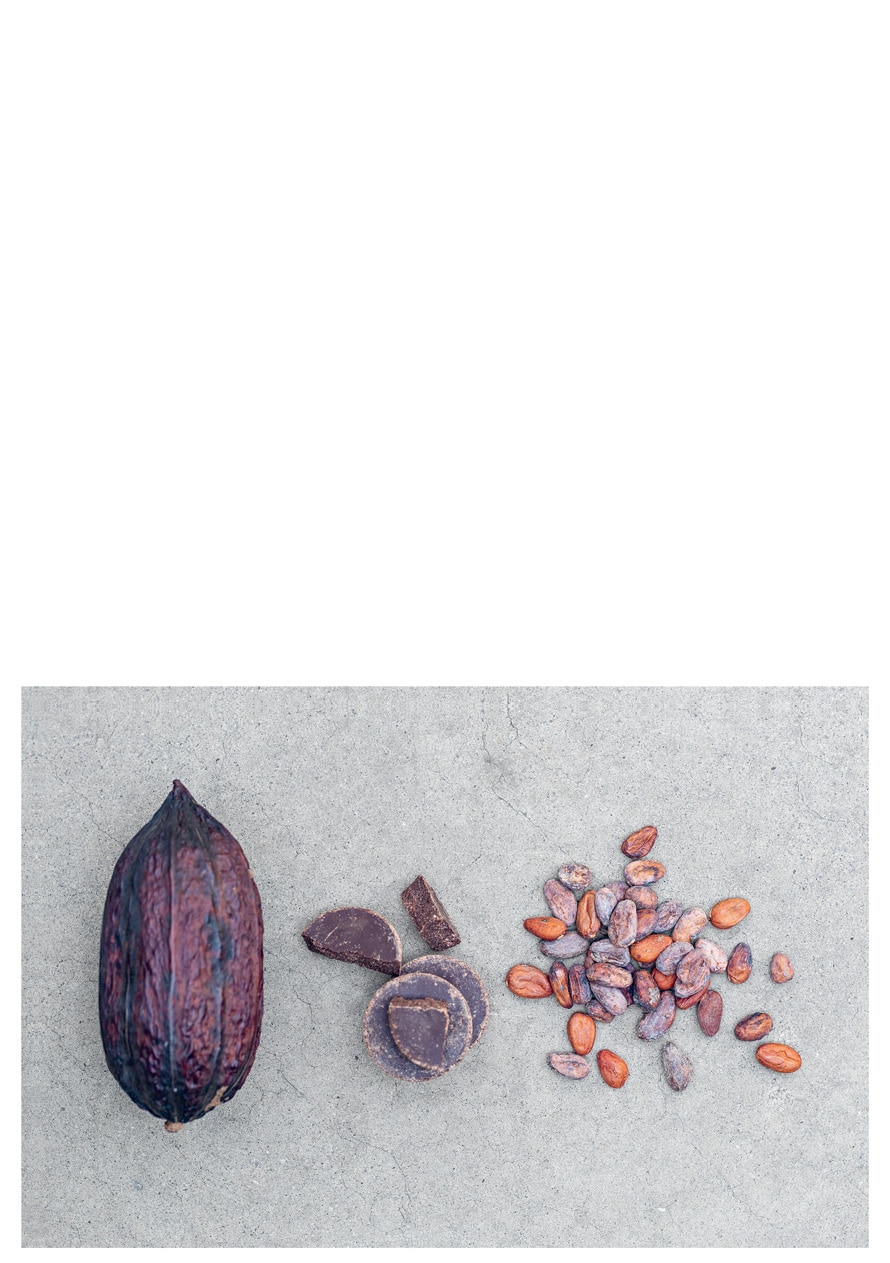

The main benefit of cacao is a beverage they make and call chocolate [...]. It is a precious drink, wherewith they feast noble men who come or pass through their lands [...]. They use spices and much chili, they also make paste and say it is pectoral and for the stomach and against catarrh.8

José de Acosta, The Natural and Moral History of the Indies, 1590

Legend has it that Quetzalcóatl, god of air and winds, presented the Toltecs with a cacao tree and taught the women how to toast its seeds and grind them into a dough, to which they afterwards added water and flowers to make cacahuatl, a scented drink reserved only for its most beloved creatures.

Cacao is one of the greatest treasures that Mesoamerica bequeathed to the world. It arrived in Europe with the Spaniards, who after the conquest returned to the Peninsula loaded with the “food of the gods”. It was so important in the New World that it was used by the Aztecs as currency, food and drink.

Hernán Cortés recognized the great nutritional value of the cacao- based drink and distributed it among his soldiers. He wrote in his Letters of Relation: “A single cup of this drink gives the soldier enough strength to walk for an entire day without eating anything else”9. Cortés invited his countrymen to drink it with plenty of foam, in the style of the natives, but sweetened with sugar and then with milk.

The taste of chocolate conquered Europe and its energetic virtues were highly appreciated by students and religious people. The chocolate ritual became so popular that it turned into a palatial custom known as “warm reception”, which consisted in guests being offered a cup of chocolate with sweet rolls.

Each country experimented with chocolate, giving it new uses, and recipes. In the 17th century in England it was used for the first time in the preparation of a cake; and by the middle of the 19th century, in the Netherlands, the hydraulic press was used for the extraction of cacao butter, the raw material that revolutionized confectionery by opening the possibility to obtain solid chocolate, in order to create endless shapes and combinations.

Along with maize and beans, squash was one of the main ingredients in the milpa, the most important Mesoamerican crop-growing system. In An Account of the Things of Yucatán, Diego de Landa described the versatility of the uses of squash during the 16th century: “The seeds of some are good for making stews, others for eating roasted, and others for making vessels for their use”.11 This vine plant is one of the few of which fruits, flowers, seeds and guides can be used entirely.

The nutritional composition of squash, rich in magnesium and zinc, strengthens the immune, cardiovascular and nervous systems; it prevents chronic fatigue and depression, and optimizes learning in children. Its consumption also contributes to skin, bone and teeth health.

Sweet potato is among the main tuber crops in the world. Its name in Spanish comes from the Nahuatl word camohtli, which means “edible root”.

Historian Cristina Barros tells the story of how this tubercle saved millions of Chinese from starvation in the 1960s, explaining why its cultivation is sought and respected in China.

Due to its high content of carbohydrates, fiber, antioxidants, beta-carotenes, vitamins and minerals, sweet potato’s nutritional value is greater than that of potatoes, a great reinforcement in cases of malnutrition. For this reason, in some regions of Africa they refer to it as the “protector of children”. In fact, in Mexico there is a program dedicated to promoting the use of sweet potato in baby food.

The variety of wild sweet potato, which grows around Lake Chapala, Jalisco, has been attributed with medicinal properties, especially as a hormonal regulator in climacteric states.

Its name comes from the Nahuatl word chiactic, which means “thing full of oil”. It is an herbaceous plant of the Lamiaceae family that contains a high concentration —even greater than that of salmon— of alpha-linolenic omega-3 fatty acid.

The Maya and Aztecs considered it the ideal food for warriors, a source of energy for long journeys. The Tarahumara, called “the people born to run”, are nourished with izkiate, an energy drink made from chia seeds.

Chia is becoming one of the most popular superfoods thanks to its nutritional properties.

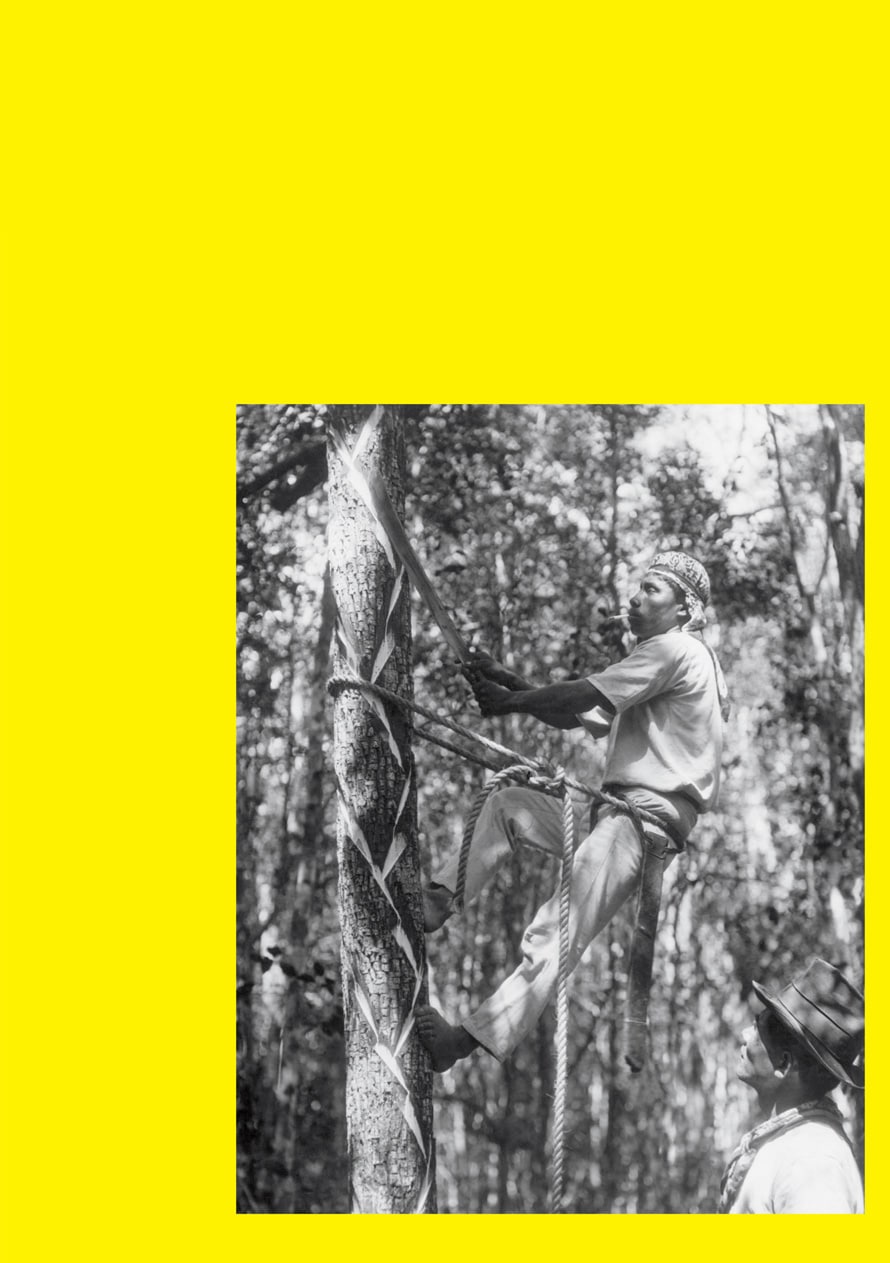

The Maya obtained tzictli from the resin extracted from the bark of the sapodilla tree —also known as the “chicle tree”— and used it for chewing, to clean their teeth, and as a distraction from hunger and thirst.

The industrial development of chewing gum, as we now know it, began in the United States at the end of the 19th century. The story tells that General Antonio López de Santa Anna offered a ton of tzictli resin to inventor Thomas Adams, who, without much success, tried to use it to manufacture tires. Upon knowing its use as a masticatory, Mr. Adams experimented by mixing it with paraffin and thus invented a chewable product that he began to market in 1869. Years later, flavor was added to the mixture and company Adams New York Gum took off.

Chili is the king of Mexican cuisine as it provides smell, color and flavor to all our dishes. Red, green, yellow, orange or black, those that are hot and those that are not... it is estimated that there are between two and three thousand types of chili in the world.

Its origin is Capsicum annum, whose oldest evidence are the seeds in the Coxcatlán cave, in the region of Tehuacán, Puebla, dating from between 6900 B.C. and 5000 B.C.15

It is one of the ingredients of the New World that sparked the most curiosity in Spaniards, since indigenous people paid tribute to Tlatlauhqui cihuatl ichilzintli, the “respectable lady of the red little chili”.

In addition, it was commonly used for its medicinal properties: cavity disconfort was cured by pressing a hot chili with salt against the infected tooth, chili accelerated labor, it was a remedy for constipation, and even served against the “evil eye”.

“Yellow beans, red, white and the smaller ones, those that are marbled, others of very diverse colors, and those that are very big like broad beans, which are referred to in their language as ayecotli”,20 is how Bernardino de Sahagún describes the great variety of beans found in the New Spain.

Beans are a symbol of our national identity and a pillar for the country’s economy; together with chili and maize, they constitute the great Mexican gastronomic triad.

Currently over 150 varieties of beans are known in the world. In France, all types of beans are called haricot, referring to ayecotli.

Beans have been consumed since pre-Hispanic times, taking advantage of all the life cycles of the plant: seedlings eaten as pigweed, green beans —immature pods— and the cooked mature grain.

With over 549 species, Mexico is a world leader in edible insects. Entomophagy is the legacy of ancient Mexicans who consumed very little meat in their diet, since insects represented their main source of protein.

In the Florentine Codex, 96 species of insects are described; the favorites in the pre-Hispanic diet were the honeypot ants (necuázcatl), ant eggs (azcatlmolli), maguey worms (meoculli) and grasshoppers (chapolin).

Currently, mosquitoes and arthropods are still part of the diet of Mexicans: scorpions, stink bugs, larvae, ahuautles (hemipteran insect eggs), leaf-cutter ants, cuchamá worms, crickets, flies, termites... And many more are the perfect appetizer, seasoned with lime juice, chili, garlic and onion. In addition to their high protein content they are rich in iron and other nutrients, making their consumption very healthy.

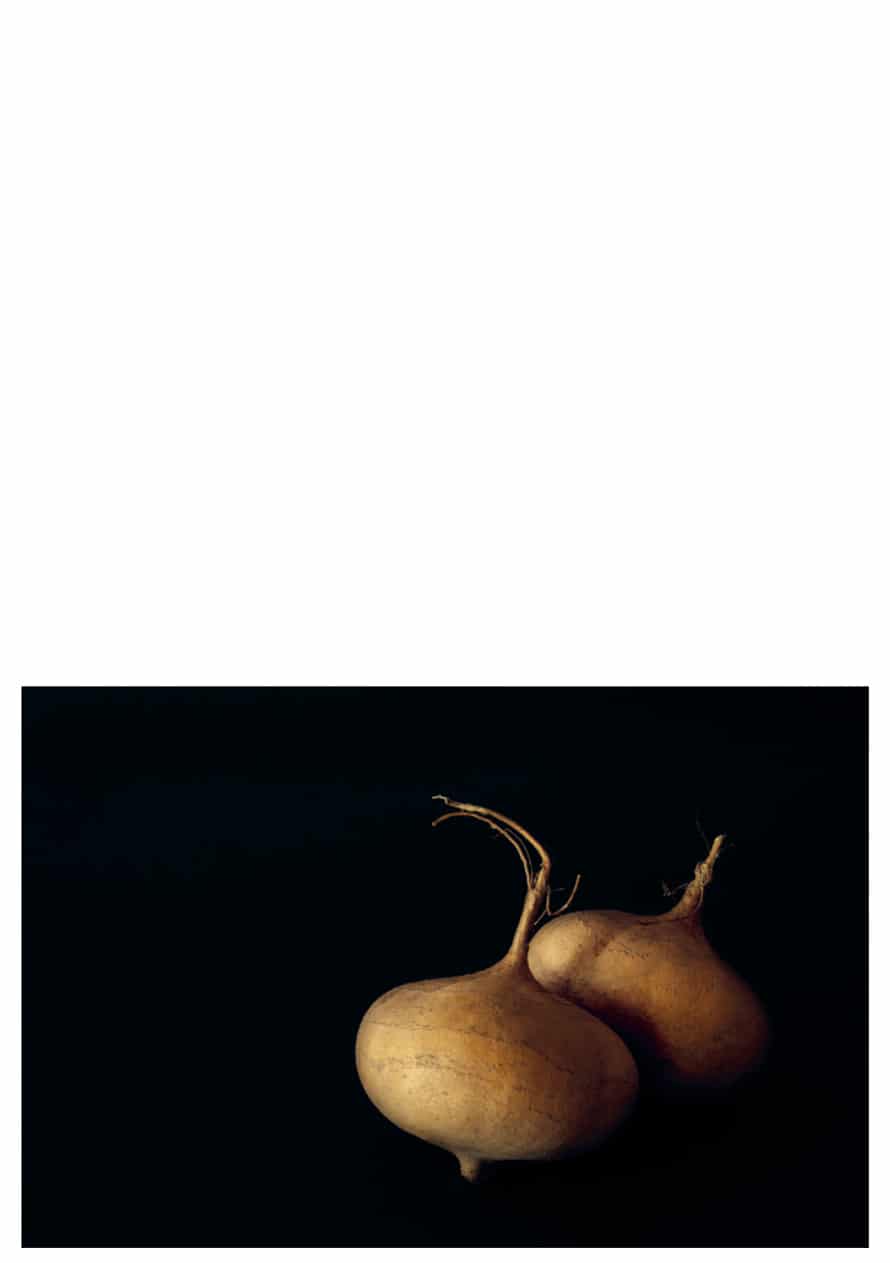

The name of this tuber comes from the Nahuatl word xicamatl, which means “root that gushes juice”. The fleshy and fresh features of its texture made it one of the desserts preferred by the Maya as a means to deal with the heat.

In Natural History of New Spain, Francisco Hernández describes the properties of jícama: “They quench thirst, combat heat and the dryness of the tongue, provide a food very appropriate for those persons who have a fever, and nourish the body [...]. I have heard it is said that these roots have been transported to Spain, preserved with sugar or covered with sand”.26

The Spanish conquerors took this watery root to the Philippine Islands, extending later to many parts of Asia, where it was adopted as an ingredient in several traditional recipes.

Xiltómatl, a Mesoamerican ingredient, of which the Nahuatl root means “navel”, was domesticated by the Aztecs, who offered the best examples of this fruit, accompanied by flowers and copalli, to Tlazotéotl, goddess of passion and lust.

From Mexico it traveled to the Old World in the hands of Hernán Cortés. In Spain, for a long time its use was reduced to an ornamental plant, because they believed it was poisonous.

It was in Italy where they discovered its quality to adapt and mix with other ingredients, so they named it pomodoro, that is “golden apple”, and perfected its cultivation until it became an increasingly large, juicy, strong fruit of multiple and voluptuous shapes. Presently, over two thousand tomato varieties are known and it is considered one of the most important ingredients on the planet. The current Mediterranean diet and innumerable Mexican dishes would be inconceivable without it.

According to the Popol Vuh poem when the gods gave rise to the Earth they decided to create man and to make him out of mud, but it lacked strength, so they later experimented with maize and thanks to the divine grain, man had the strength and sufficient intelligence to populate the world.

Maize is the greatest gift that Mexico has given the world. Thanks to its social, economic and cultural importance, it is the most representative crop in the country and its consumption is closely linked to Mexican history, traditions and gastronomy, both for its high nutritional value, and for its versatility and important healing properties.

It all started with teocintle, the wild maize seed that was domesticated about eight thousand years ago and the oldest vestiges of which were found in Tehuacán, Puebla. In Latin America alone, approximately 220 races of maize have been classified, of which 64 are produced in Mexico and 59 are exclusive to the country.

The variants of its use and consumption are countless: you can eat the cob (cooked or roasted); threshed, as esquites or in dishes such as pozole or maize soup, made with cacahuazintle maize. The dough from which tortillas, soups and other variants are produced is made from the ground grain.

The fungus that grows in maize is known as huitlacoche, “delicacy of the gods”. The ear is used to make atole andtamales —which are wrapped in maize leaves or totomoxtle. Maize “hair” has medicinal properties, especially useful to fight kidney diseases. The dried grains are considered “wise”, that is why they are used in ceremonial rites and serve in foretelling the future.

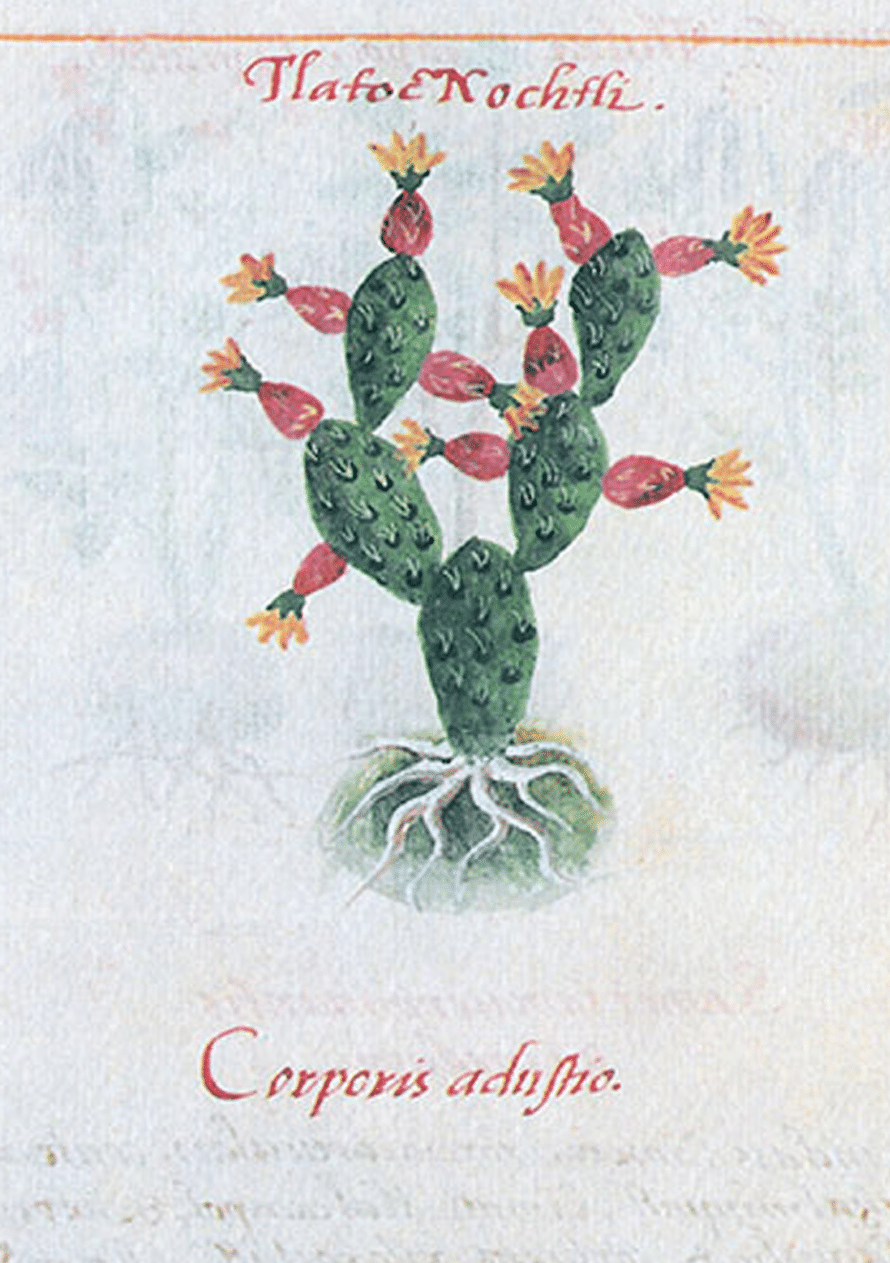

In the description of his discoveries in New Spain, Friar Bernardino de Sahagún speaks of a variety of “monstrous” trees, of which the edible leaves and fruits are part of the natives’ diet. He refers to nopalli, a plant of the cacti family, sacred to the Aztecs because they considered that its roots connected with the underworld, and the prickly pears, also called “sacred hearts”, with heaven.

This ancestral ingredient is an icon of our identity, an essential element of Mexican cuisine and landscape, immortalized in the national emblem by the myth of Mexico-Tenochtitlan's founding, where the Aztecs witnessed the eagle devouring the snake standing on a paddle cactus.

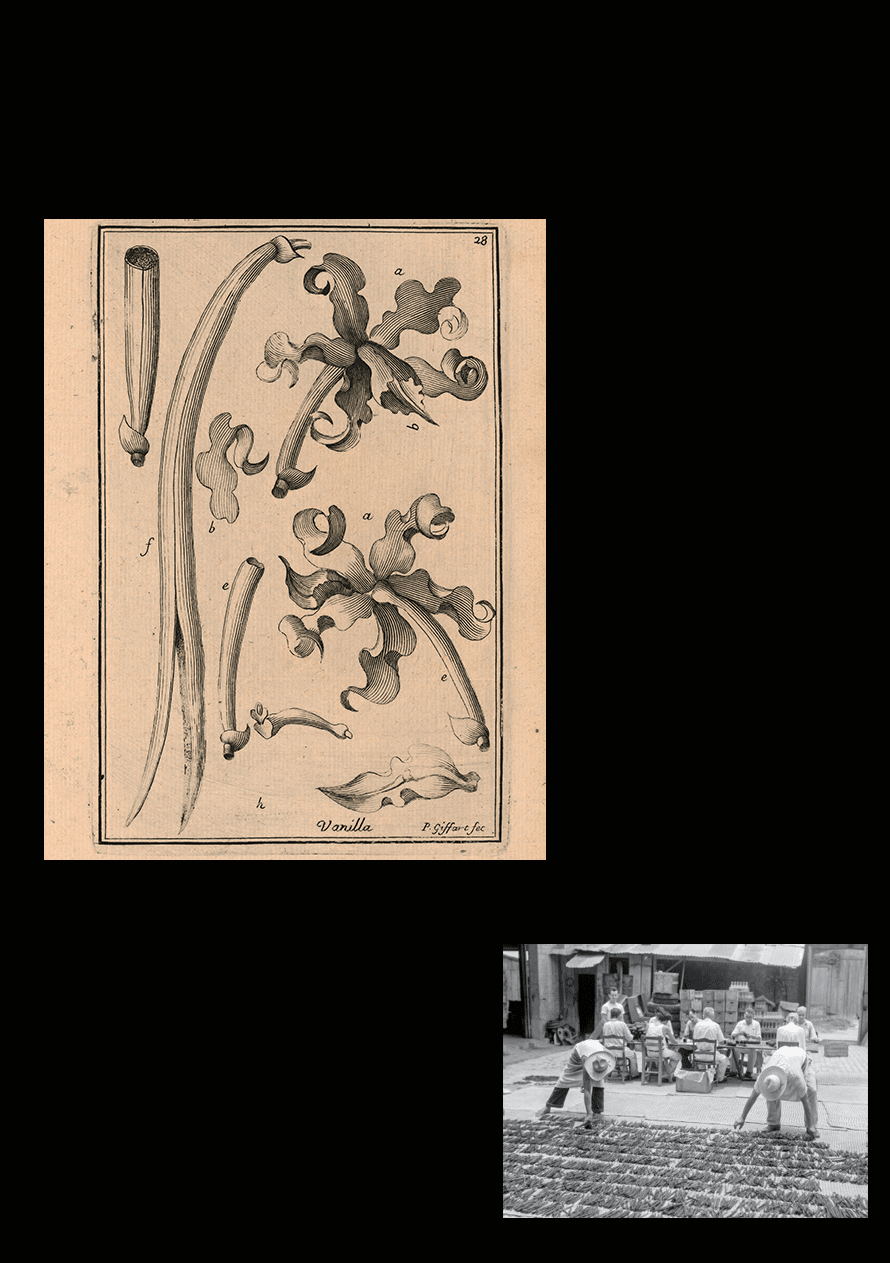

The pod of this orchid was much appreciated by the Aztecs, who mixed it with cacáotl to give it fragrance and flavor; they consumed it dissolved in water as nourishment for the brain or as a remedy against venom and bites of poisonous animals. Its name in Nahuatl is tlilxóchitl, which means “black flower”.

After the conquest it was taken to Spain to make perfumes and add scent to chocolate. In his Universal Dictionary of Natural History, Valmont de Bomare stated that among its benefits, “vanilla fortifies the stomach, helps digestion, dispels flatulence, promotes periods and urination, facilitates birth, and the English specifically appreciate it for banishing the effects of melancholy”.56

In France it was not only used in perfumery and medicine, but also for baking. Kitchens all over the world have been flooded by the enveloping aroma of vanilla, considered one of the most used flavorings on the planet.

The legend of its origin is pre-Hispanic from Totonac mythology, and tells how Tzacopontziza —“bright star of dawn”— daughter of king Tenitztli the third, had taken chastity vows, consecrated by her father to the service of Tonacayohua, the goddess of sowing and food, but fell madly in love with prince Zkotan Oxga —“young deer”. The young lovers fled, a sacrilegious act that had to be punished with death, so they were persecuted, imprisoned and their throats were slit. Their hearts in love were offered to Tonacayohua, and an orchid of exquisite aroma grew on the site of the sacrifice.