In the history of mankind, the recurring custom of creating figurines is found in different eras and cultures, and has been used for different purposes.

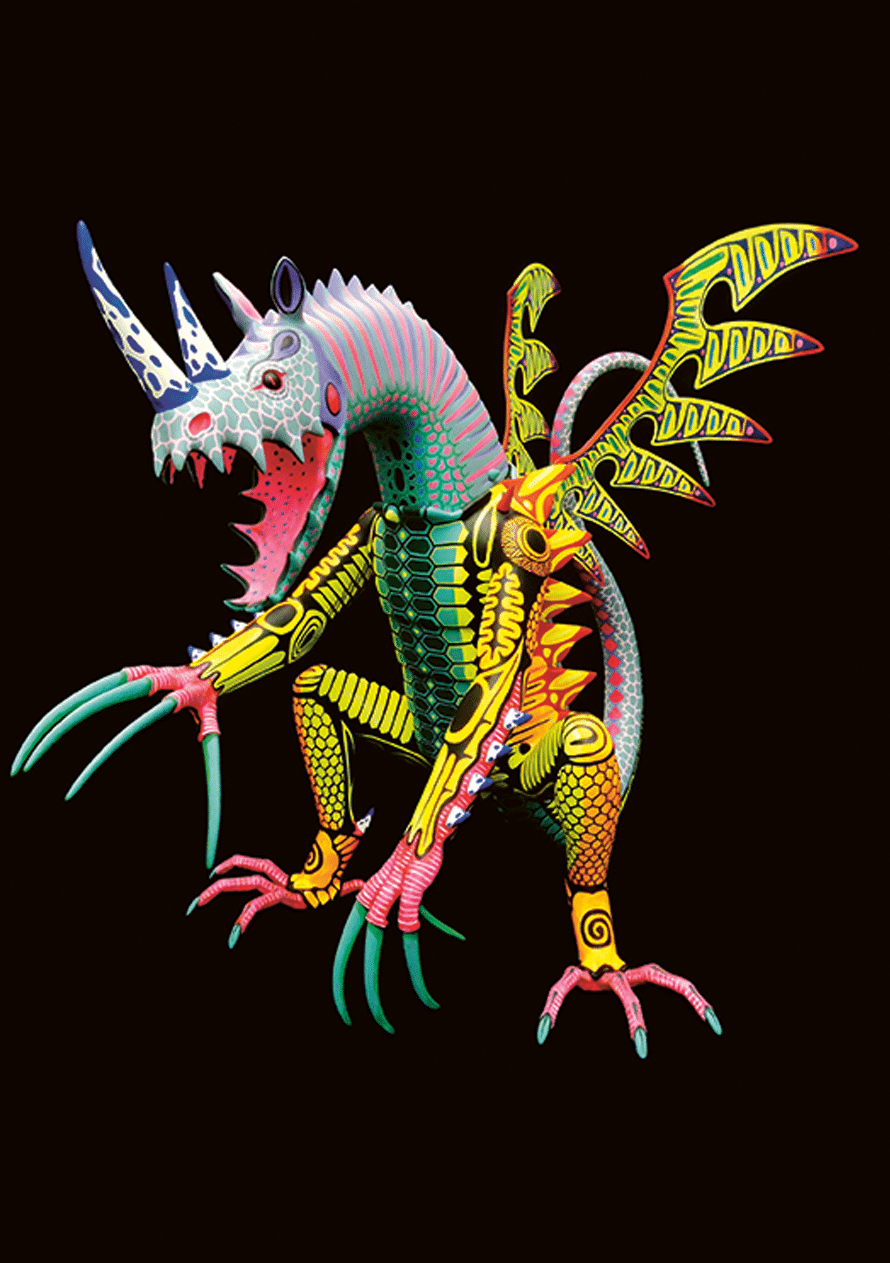

In Mesoamerica, Quetzalcóatl may well be the precedent of alebrijes, the colorful and mythical creatures that came to Mexico to protect the life and death of those who dream.

From 1927, Don Manuel Jiménez in Arrazola, in Oaxaca, and in the 1940s, Don Pedro Linares, in Mexico City, used these figures and forged a milestone in Mexican folk art history, making them from wood and cardboard, respectively.

Today, thanks to an impressive acceptance, alebrijes have become a reference of folk art.

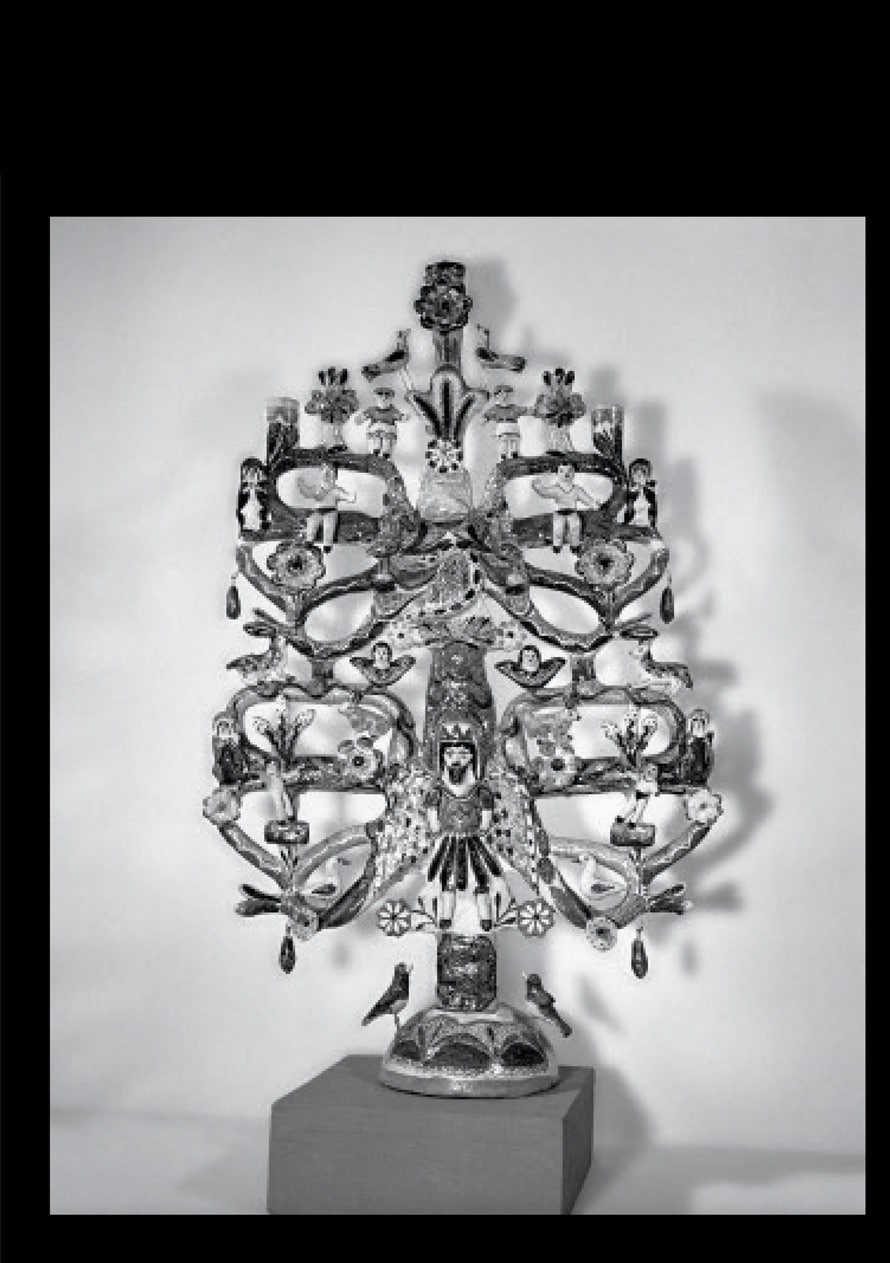

The tree of life is one of the most renowned Mexican handicrafts worldwide. Its origin dates back to pre-Hispanic times, when the Teotihuacan, Otomi, Matlatzinca and Mexica peoples used clay to make ceramics for ceremonial uses and utensils for everyday life.

During the spiritual conquest, in the colonial era, clay deities were replaced by a tree of life —a representation of the biblical creationist theory— as an instrument of evangelization. Over time, indigenous artisans appropriated the allegory transforming it from a religious object to a folkloric representation accounting for the worldview of each craftsman.

Trees of life are produced in Izúcar de Matamoros, Puebla; in Acatlán, Puebla; and especially in Metepec, State of Mexico. They have been exhibited in museums in Europe, Asia and North America as valuable artistic objects.

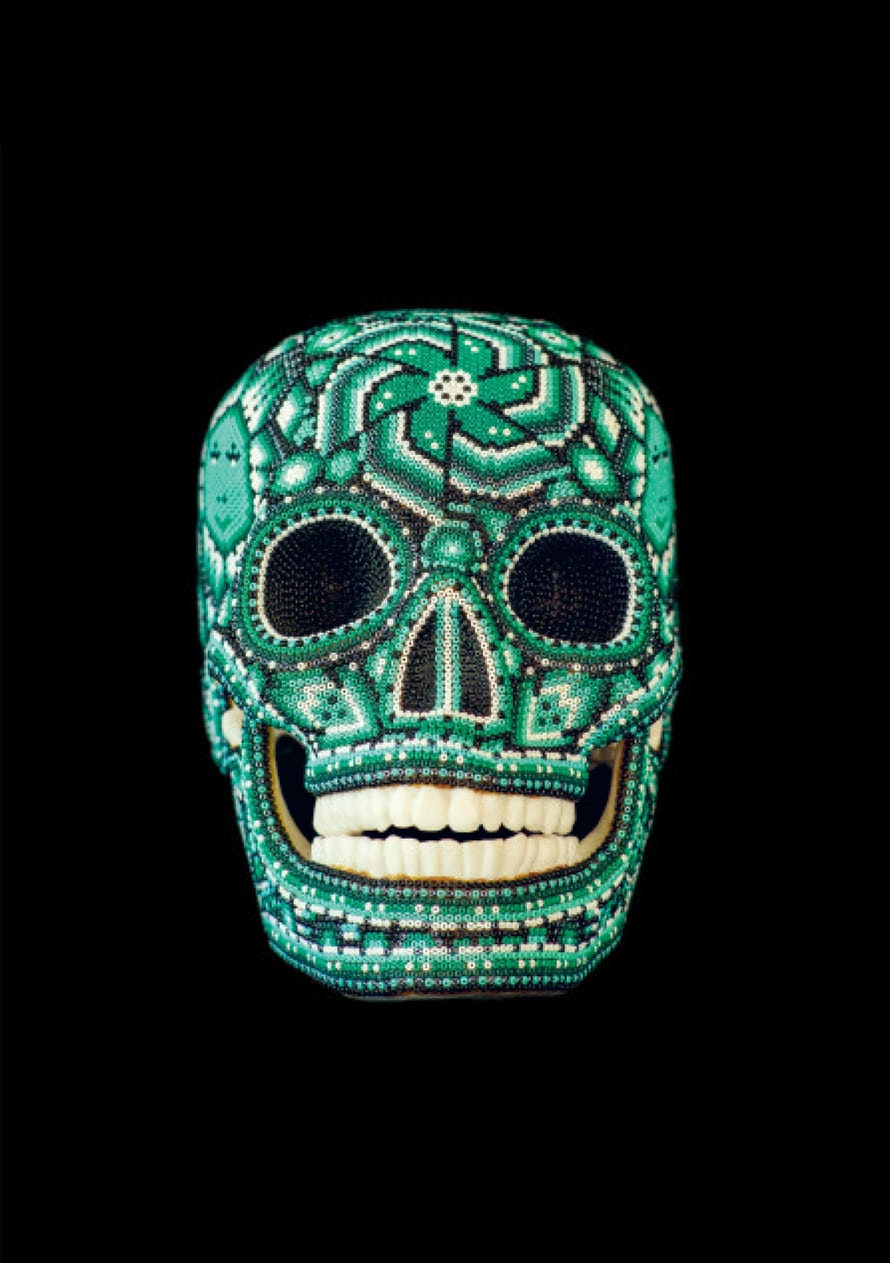

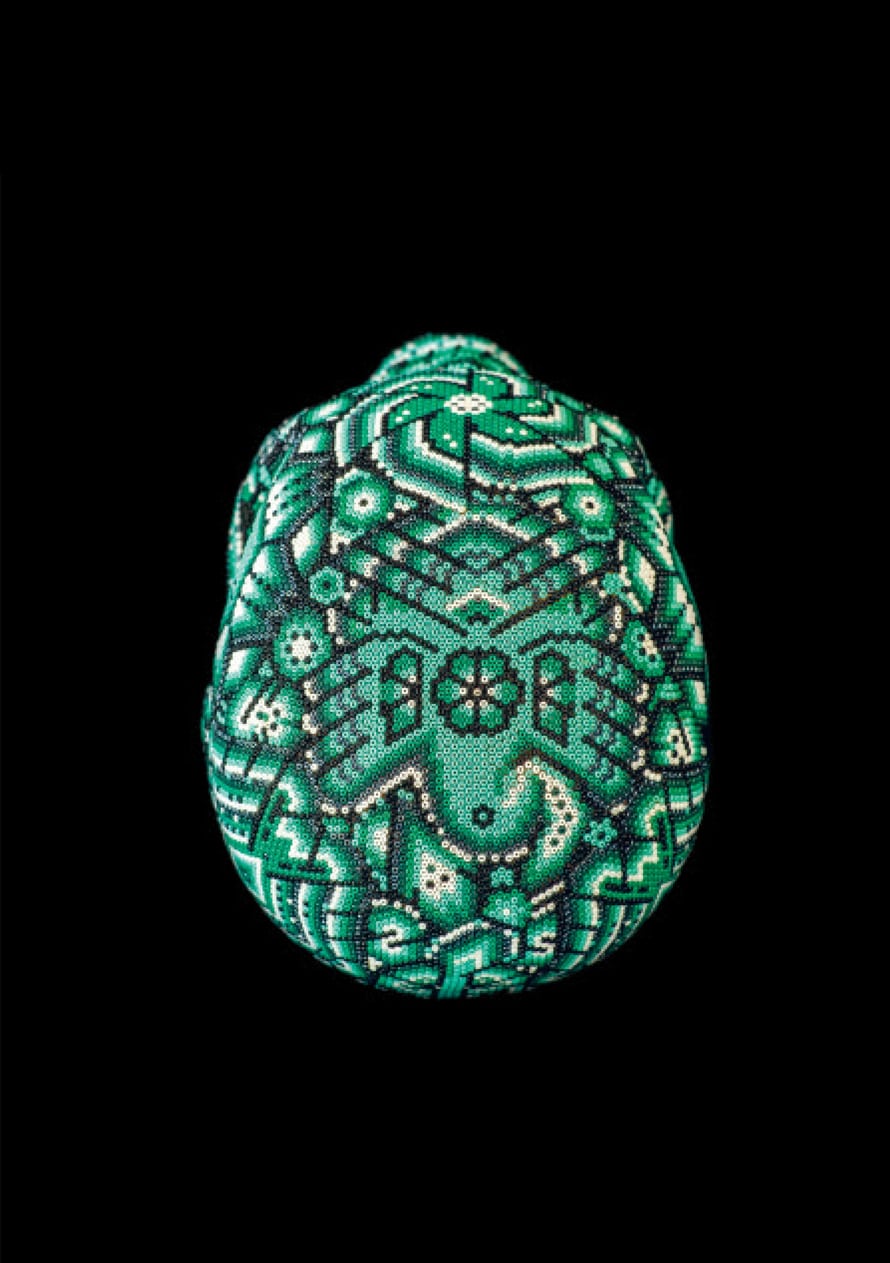

Appreciated throughout the world, Huichol art was born as an offering to the gods. It is created by the hands of an ethnic group that lives in the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range of Mexico, which includes the states of Jalisco, Nayarit, Durango and Zacatecas.

Like a sacred script that protects history and tradition, Wirraritari artists use colors, symbols and geometric figures, combined with everyday forms to make their creations on beaded sculptures, yarn pictures and jewelry, which become representations of their worldview. More than work, for these artists each of their pieces means the opportunity to communicate with the creator.

For the Huichol, nierika is the gift of seeing, a mirror where their shaman, the marakame, can observe images stemmed from a magical world, which can be entered with peyote cactus; it is an ancestral tech- nique through which artists find different ways to materialize the messages of divinity.

Although now they use plastic beads and yarn —stuck with beeswax and pine resin—, these works were originally made with seeds, shells, small stones and feather filaments. The production of each piece takes an average of 50 hours, during which the artists pray to restore harmony that should exist between all beings that inhabit earth.

Black clay —also known as black ceramic— is a pottery style, iconic of Oaxaca. Its origins go back to the archaeological remains of domestic crockery made by Zapotec and Mixtec peoples of the Central Valleys.

Until the first decades of the 20th century, craftsmen of the village of San Bartolo Coyotepec made various rustic utensils of matte and grayish clay for daily use: jugs, amphoras, owl figures used as mezcal bottles, apaxtle bowls to store water, flutes, whistles and toys, among others.

In 1950, Mrs. Rosa Real Mateo de Nieto, successor of the pottery artisans, experimented in her workshop until she discovered that the color and brightness of the pieces could be changed by polishing and cooking them at a slightly lower temperature. Thus black clay was created, the most popular pottery among Mexican crafts collectors.

There are beautiful garbanceras,

wearing corsets and high heels,

but they must be calaveras,

just like all the others in the pile.

José Guadalupe Posada

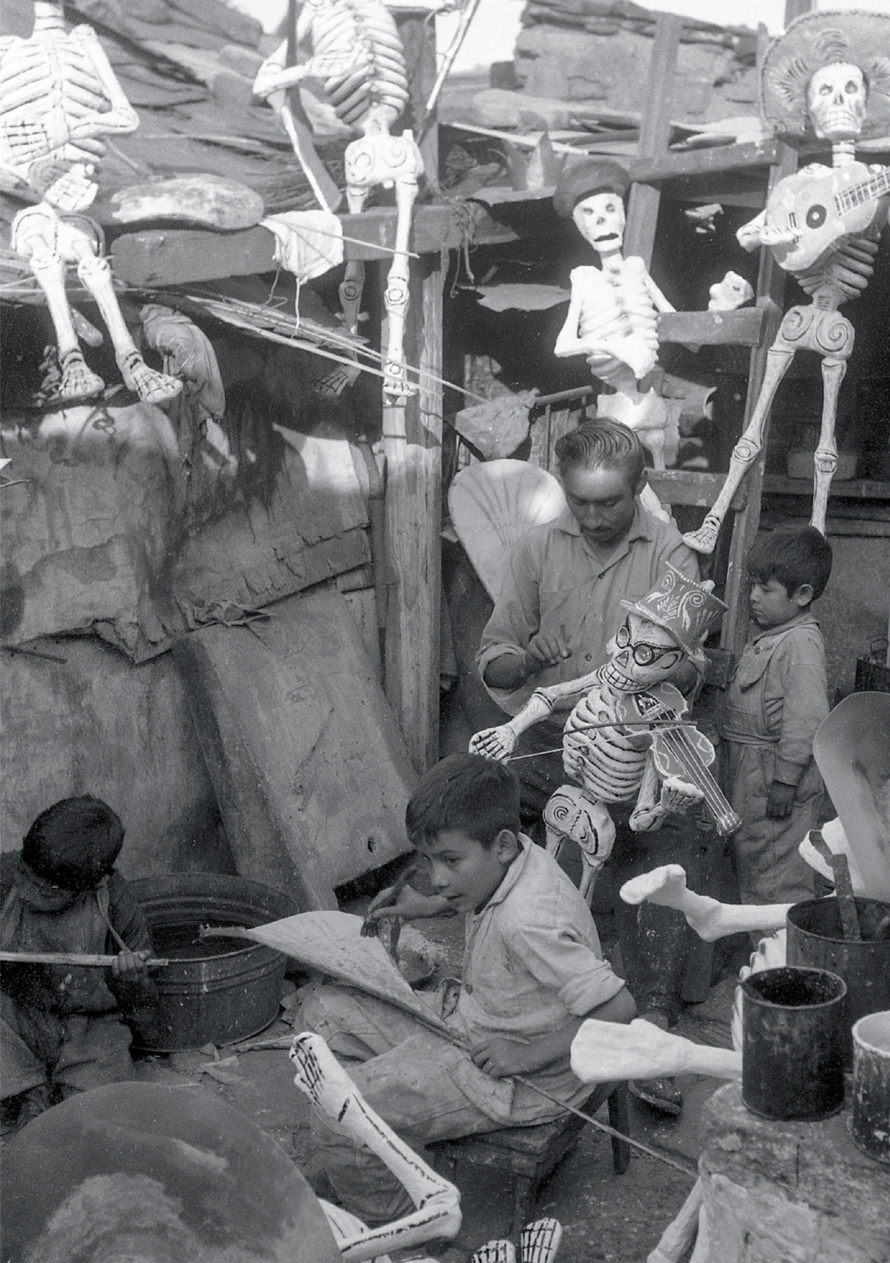

La Catrina, icon of the celebration of the Day of the Dead, was born in hands of José Guadalupe Posada. The engraver, illustrator and cartoonist, originally from Aguascalientes, was born in 1852 and dedicated his life to portraying costumbrist, folkloric and social critic scenes that he published in printed media such as La Patria Ilustrada, Revista de México and El Ahuizote, among others.

Posada is considered a universal Mexican artist, whose work gave an account of the great contrasts of the revolutionary era: the marginalization, pain, death and discontent of the people, inevitably merged with life, pleasure and joy.

The image of the “Calavera garbancera” began to circulate in November 1913 —eleven months after Posada’s death— and together with the other skeletons and literary calaveras he illustrated a tradition that continued to live far beyond the death of its creator.

It was muralist Diego Rivera who took the garbancera from the pile and dressed her in an elegant gown and a feather stole to appear in the Dream of a Sunday afternoon in Alameda Park mural in 1947, and named her “Catrina”.

Ever since the first pre-Hispanic cultures in Mesoamerica, shamans have been present in indigenous communities playing a role in finding solutions to social, physical and spiritual issues. They are custodians of words and safeguard ancestral knowledge.

One of the cradles of this tradition in Mexico was the lineage of graniceros, lightning ritualists, who were former servants of Tláloc, god of rain.

Shamans have different specialties: there are bone healers, midwives, fright-scarers or autochthonous psychologists dedicated to psychological disorders, among others; as well as the nahuales, considered guides. For many indigenous communities they serve as leaders, wise men, judges and teachers who practice and teach the invisible.

Many are known for distancing themselves from allopathic methods to rescue traditional healing, since they know plants, honor them and use them as a remedy for body and soul.

Shamanism lives in the memory of ancestors, whose knowledge is passed on orally, preserved in tales, myths, legends and traditions rooted in the native peoples that have survived westernization in our country such as the Nahua, Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec, Huichol, Otomi, Chontal, Yaqui and Tarahumara, to mention a few.

In this context, the figure of the shaman is configured as part of history and it is said that he brings together two realities or two worlds.

Considered the national sport, charrería is a set of equestrian skills typical of jockeys —charros— that take place in a ring known as the lienzo charro.

The origin of this practice dates back to the 16th century, in gatherings between members of different estates during the boom of cattle ranches. That is why the Mexican equestrian tradition highlights the handling of livestock while riding horses, as well as the use of saddle and rope.

Charros, dressed in their elegant suits, show off their cowboy skills with risky luck during charrerias, including the “Step of Death”; while escaramuzas, their female counterparts, combine riding with dance and perform synchronized choreographies dressed as female revolutionary soldiers known as Adelitas.

In 2016, UNESCO registered charreria in the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. In Mexico there are approximately two thousand events a year of this sport, which is also practiced in the United States, Canada, France, Panama, Cuba and Japan.

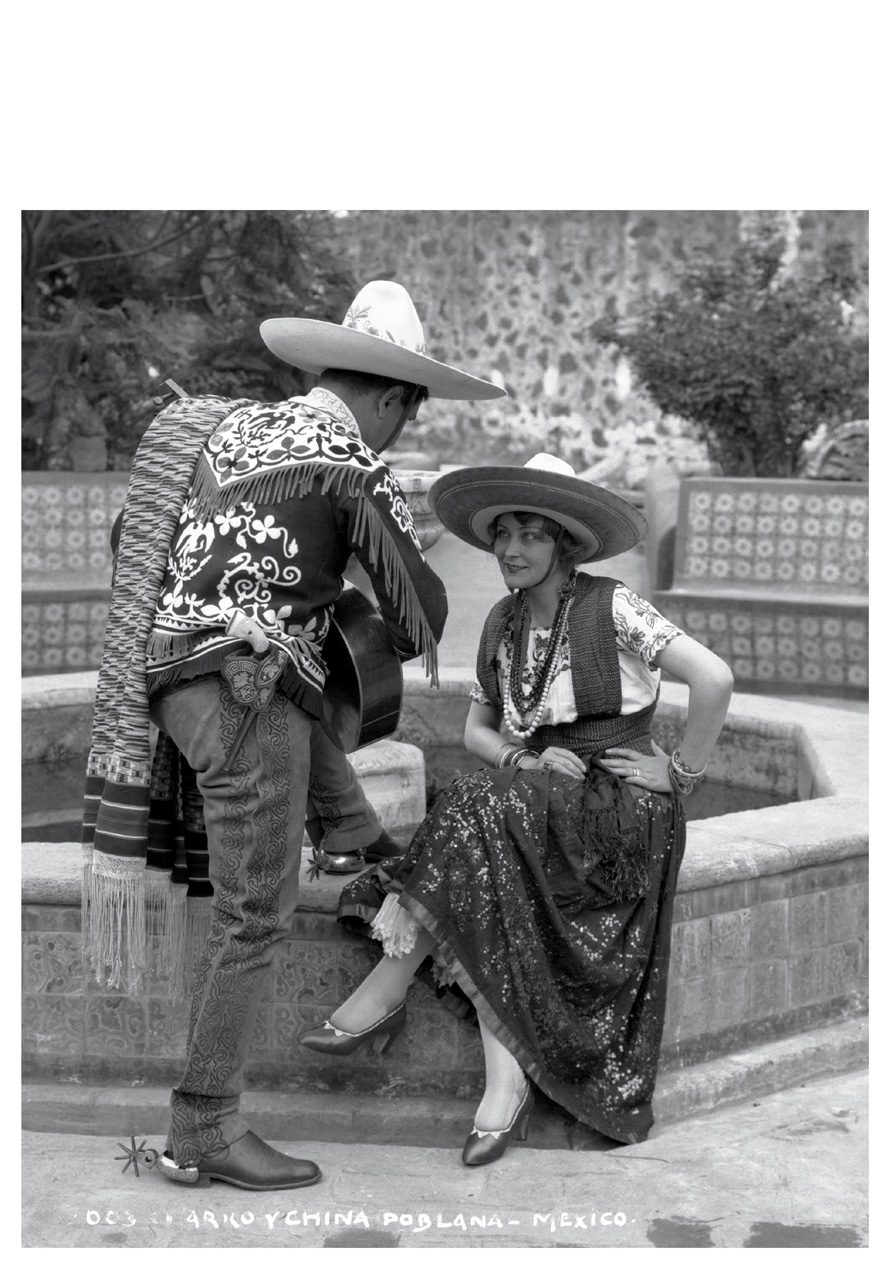

A woman with fiery and expressive eyes, olive complexion, black and fine hair, small feet, flexible waist [...], who could read, sew and cook in the style of the country, who tapped her feet to jarabes and other sones at the fandangos.16

Manuel Payno

The China Poblana is one of the symbols of Mexican identity most reproduced in history. Thousands of paintings, prints and photographs show her luxurious costume: a cloth skirt or petticoat decorated with the colors of the flag and the national eagle embroidered with sequins, a blouse with embroidered flowers, a shawl and red shoes. Always combed with braids interlaced with colored ribbons and sometimes wearing a charro hat.

The image of la China has its origins in a type of women that gained popularity in the mid-19th century. They were independent Mexican mixed race women, with very little attachment to the social and love conventions of the colonial era, captivating foreigners with their attitude and provocative and carefree dress style.

In 1919 the famous dancer Ana Pavlova visited Mexico and, in her eagerness to rediscover the country’s dance roots, she created the show Fantasía mexicana, where the Russian ballerina danced the Mexican Hat Dance in pointe shoes, dressed as China Poblana, accompanied by dancer Alexandre Volinine dressed as a charro. From then on, the image of la China was adopted by the most nationalist official dictates to represent the graces and virtues of Mexican women.

Sculptor, designer, illustrator and surrealist painter Pedro Friedeberg was born in Florence, Italy, in 1936, but he claims to have known no other country than Mexico. He disembarked in this country when he was barely three years old and grew up in a rickety house in the San Rafael neighborhood of Mexico City. Later he studied architecture, but while he was being taught angles and functional theories, he dreamed of Gaudí’s sacred geometry and fantastic organic architecture.

He worked for a while with Mathias Goeritz; however, he left the modern movement to join the rebellion of surrealism along with Remedios Varo, Edward James, Wolfgang Paalen and other artists; although only he and Frida Kahlo were acknowledged by André Bretón as part of the surrealist movement.19

In 1962 he created the hand chair, which is both a sculpture and a curious piece of design, originally made of wood finished in gold leaf, recognized and admired worldwide.

He does not remember for sure if the inspiration for this piece came to him through the fragments of a dream or from a Roman statue he saw on the Capitoline Hill, but from that same place other objects arose including tables, lamps, armchairs and countless paintings and artistic pieces in which eyes, hands, feet and psychedelic visions of his creative universe are mixed, full of humor and symbolism.

His exhibitions are innumerable and his “unauthorized” memoirs have been immortalized in the book that he dictated to poet José Miguel Cervantes, titled De vacaciones por la vida.

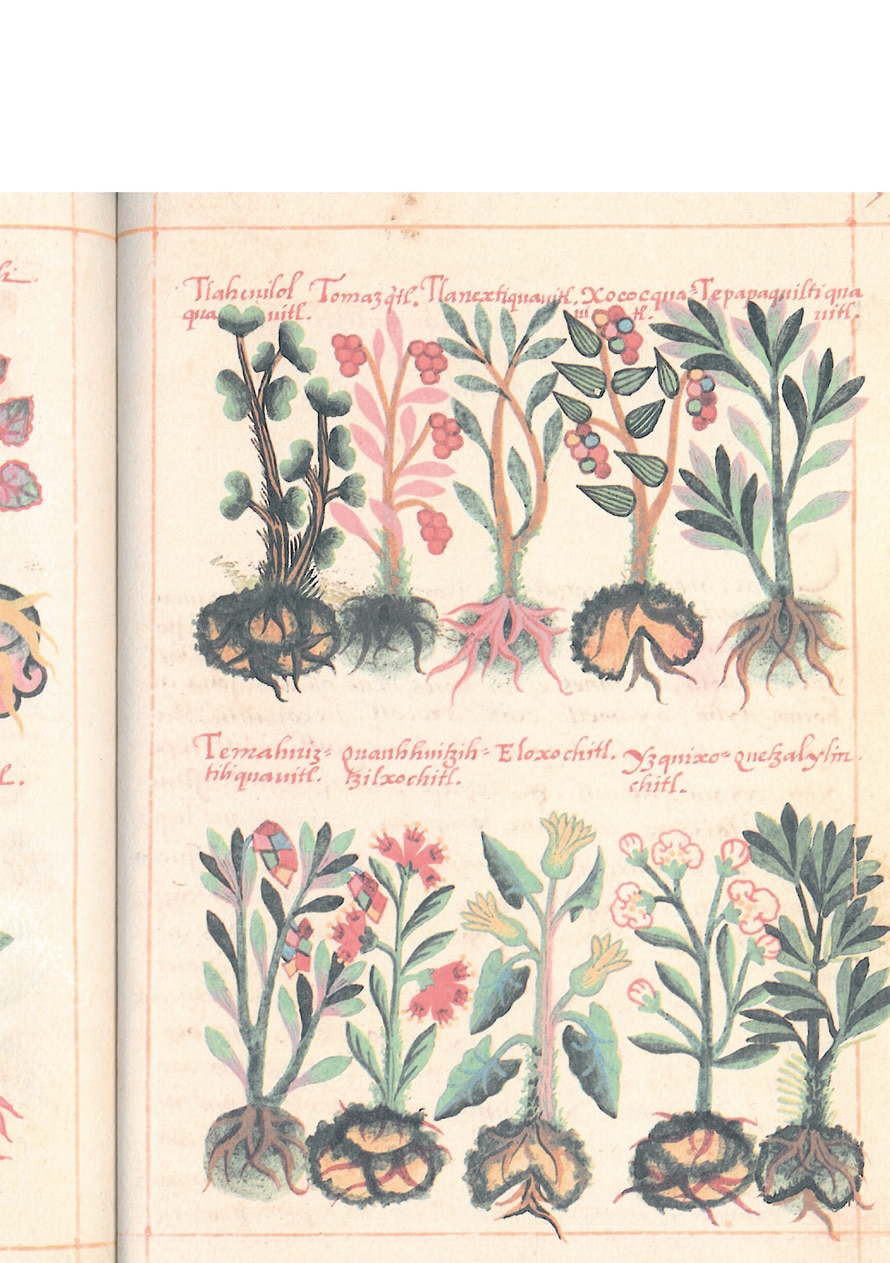

In comparison to the set of information, resources and practices that make up traditional medicine, herbal medicine is one of the most important cultural assets of our ancestral peoples that survives thanks to the efforts of shamans, healers, herbalists and grandmothers, the main keepers of this legacy.

In our country, this knowledge dates from the pre-Hispanic era. King Acolmiztli Nezahualcóyotl founded the first cultivation and research center for medicinal plants on the hill of Tecutzingo, in Texcoco.

The mural of Tepantitla, in Teotihuacán, which reproduces plants and remedies known in pre-Hispanic times, can also be seen as a vestige of this legacy, along with the Mexica sculpture of Xochipilli —prince of flowers— found in Tlalmanalco, State of Mexico, where we can observe sacred mushrooms, the tobacco flower —used by the Aztecs to attack tumors—, the morning glory flower —powerful against syphilis— and the shrubby yellowcrest —useful for the relief of bronchitis, dysentery and dermatitis.

The syncretism that came with miscegenation enriched this heritage and made it one of the largest: Mexico ranks second in the world in taxonomic richness of medicinal plants —after China— with 4,500 species.

Mexican musical instruments are those of indigenous or mestizo origin, either completely original or modified foreign instruments that evolved in our country to produce the peculiar notes of traditional Mexican music.

An example of this are mariachi’s distinctive instruments, such as the Mexican vihuela, a relative of the Spanish vihuela made of mahogany and known for its bulging shape; or the guitarrón, which replaces the double bass. Both instruments were invented in Cocula, Jalisco.

A distinguished member among the list of Mexican musical engineering is undoubtedly the requinto guitar, the essential sound in trio music. Popular all over the world, this small high-pitched guitar was invented in 1943 by Alfredo Gil, member of Los Panchos trio. A professional lute player was entrusted to carry out the order of the interpreter and composer, who was looking for an instrument of similar size to the Colombian tiple, but with more frets and the possibility of a more acute tuning, as well as an alteration that would make playing the notes easier.

Other instruments such as the jaranas —from La Huasteca and from Veracruz—, the Mexican psaltery, the chapareque, the Aztec flute, the pre-Hispanic drums, the Aztec jingles and the marimbula, are just some of the members of the immeasurable Mexican sonorous universe.

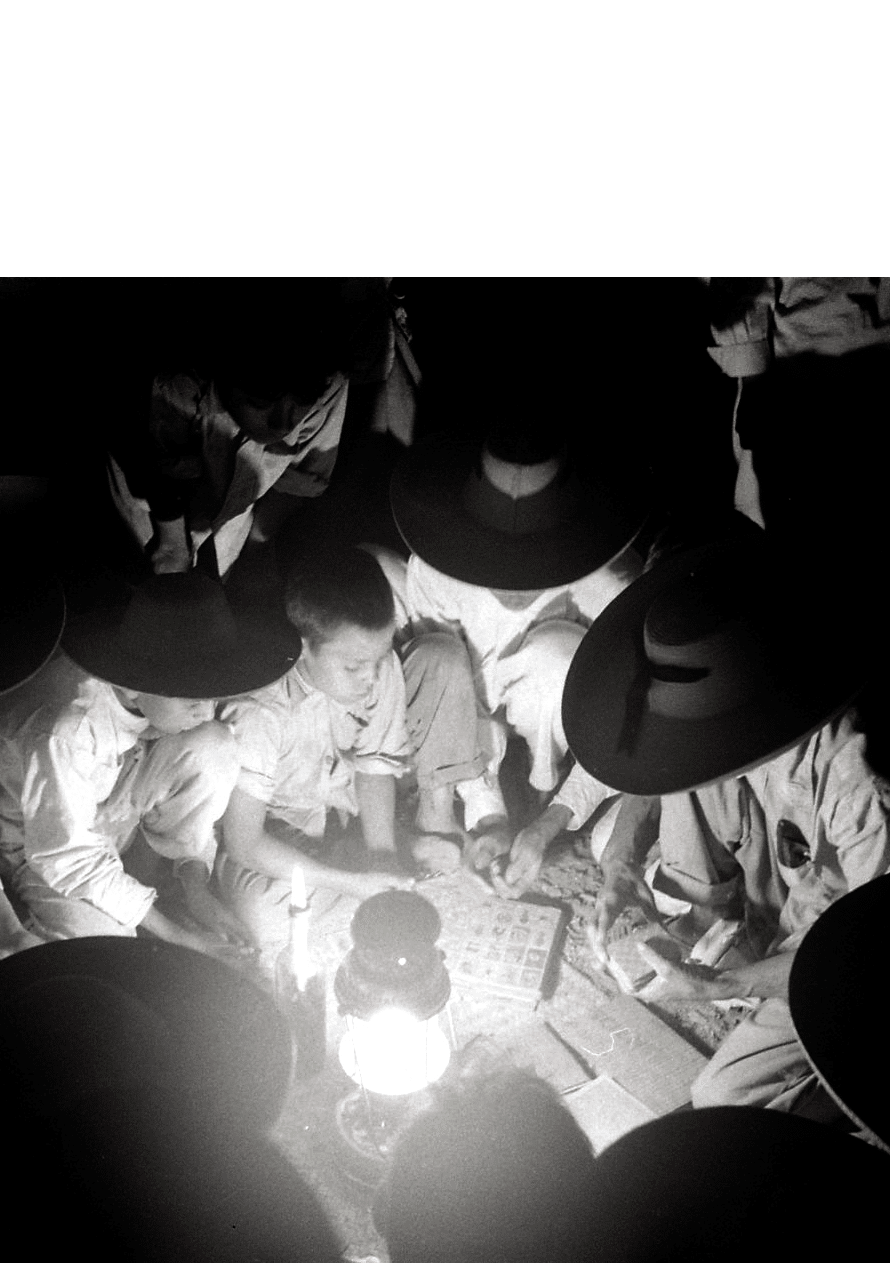

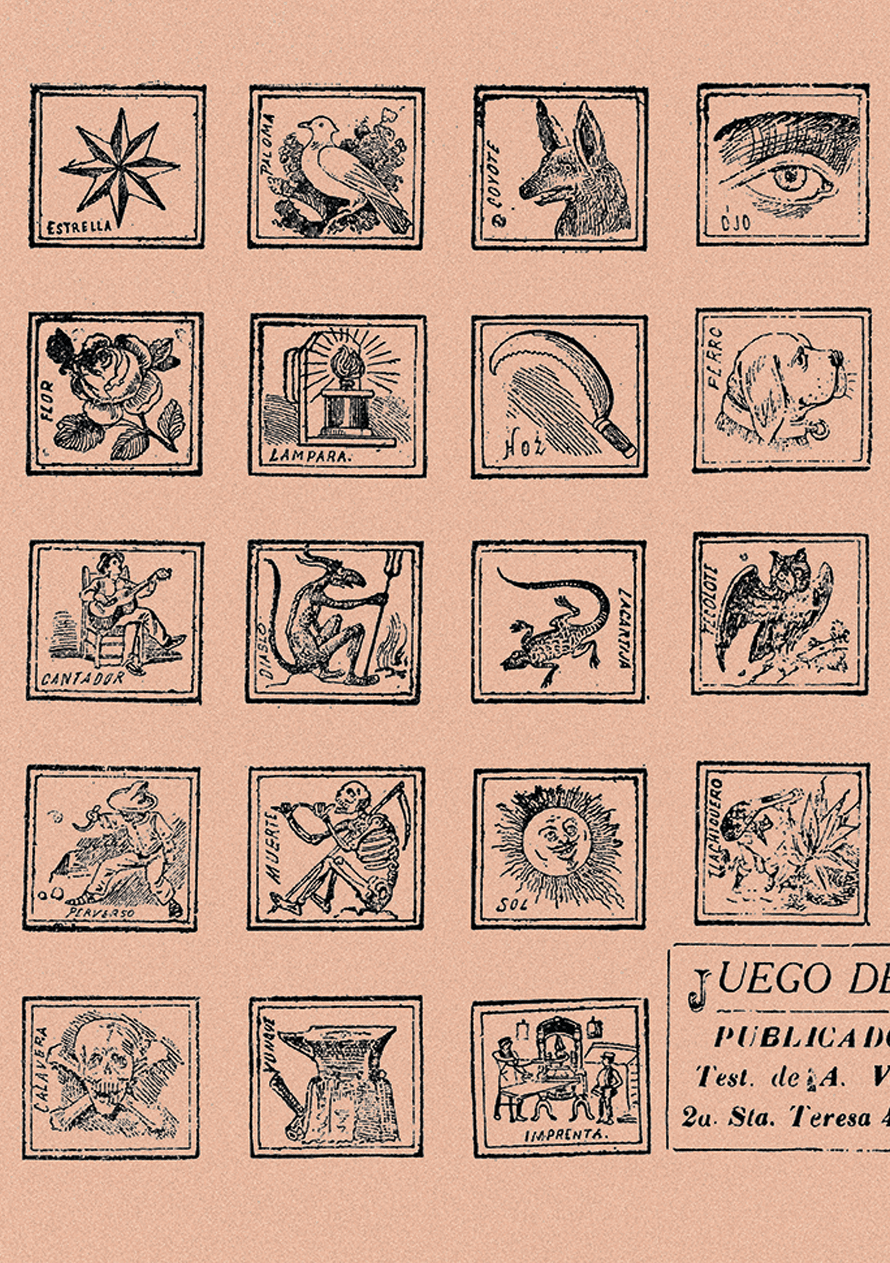

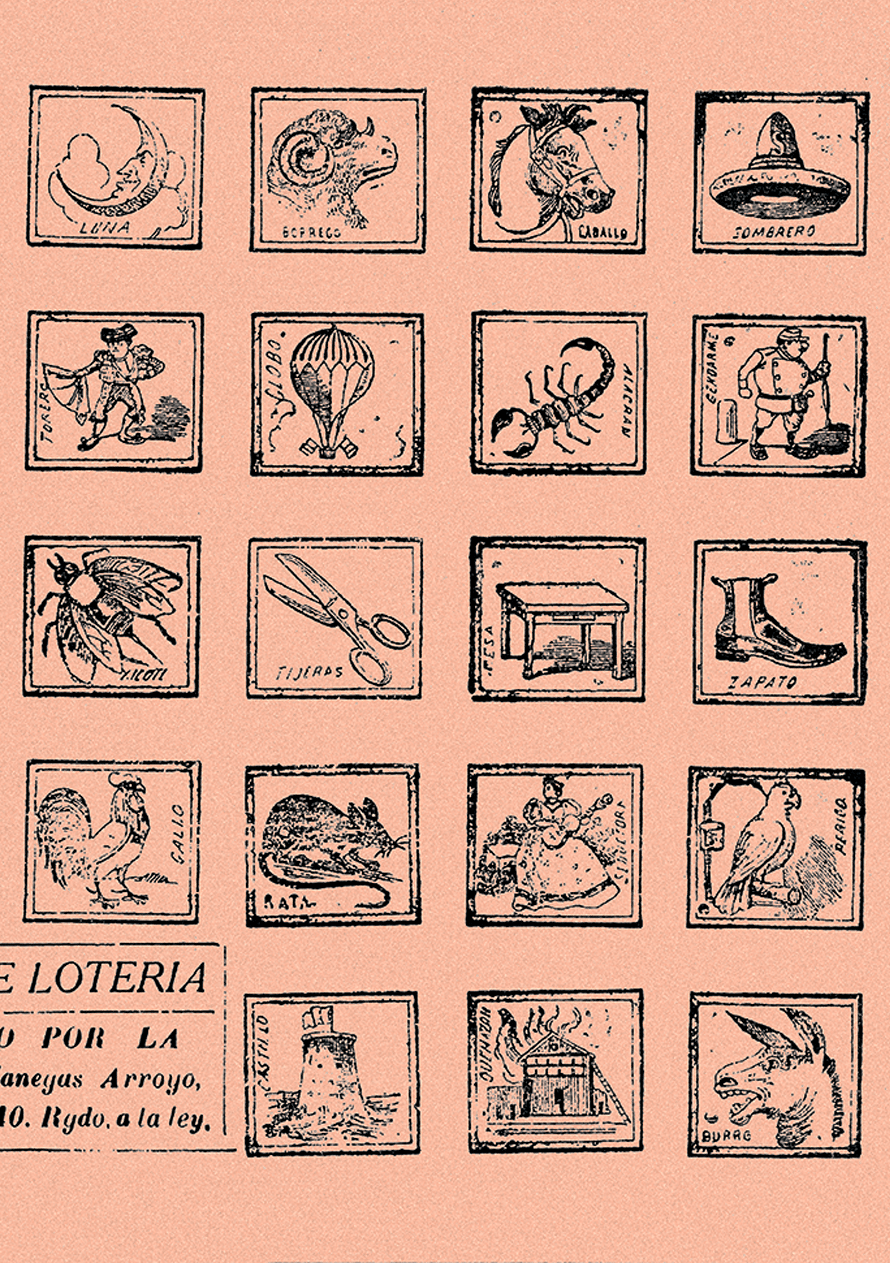

Through its traditional invitation heard on the streets to play lottery, it became one of the most representative traditional games in the country, and an essential element within the symbolic discourse of Mexican identity.

Word has it that the picture lottery was born in Italy and arrived in New Spain along with the conquerors. Later, in times of the struggle for independence, it became the favorite pastime of military troops. Of all the versions that exist, the one known as the “authentic Mexican lottery” is that one created in the 19th century by Pasatiempos Gallo, property of Clemente Jacques. It was the first industrialized lottery that was commercialized in the country and exported to other countries.

The game consists of a deck with 54 cards, each one illustrated with a traditional Mexican stamp, and with several boards or cardboard sheets with 16 random figures, which are marked with beans as each image is sung by a caller, who improvises verses and sayings to present each figure.

Pretty May 5th, the national ensign: the flag. The help of San Luis, which they call the cactus: the paddle cactus. Stay still, Valentín, do not go to fight: the brave one. Everything fits in a little jar, when you know how to place it: the jug.30

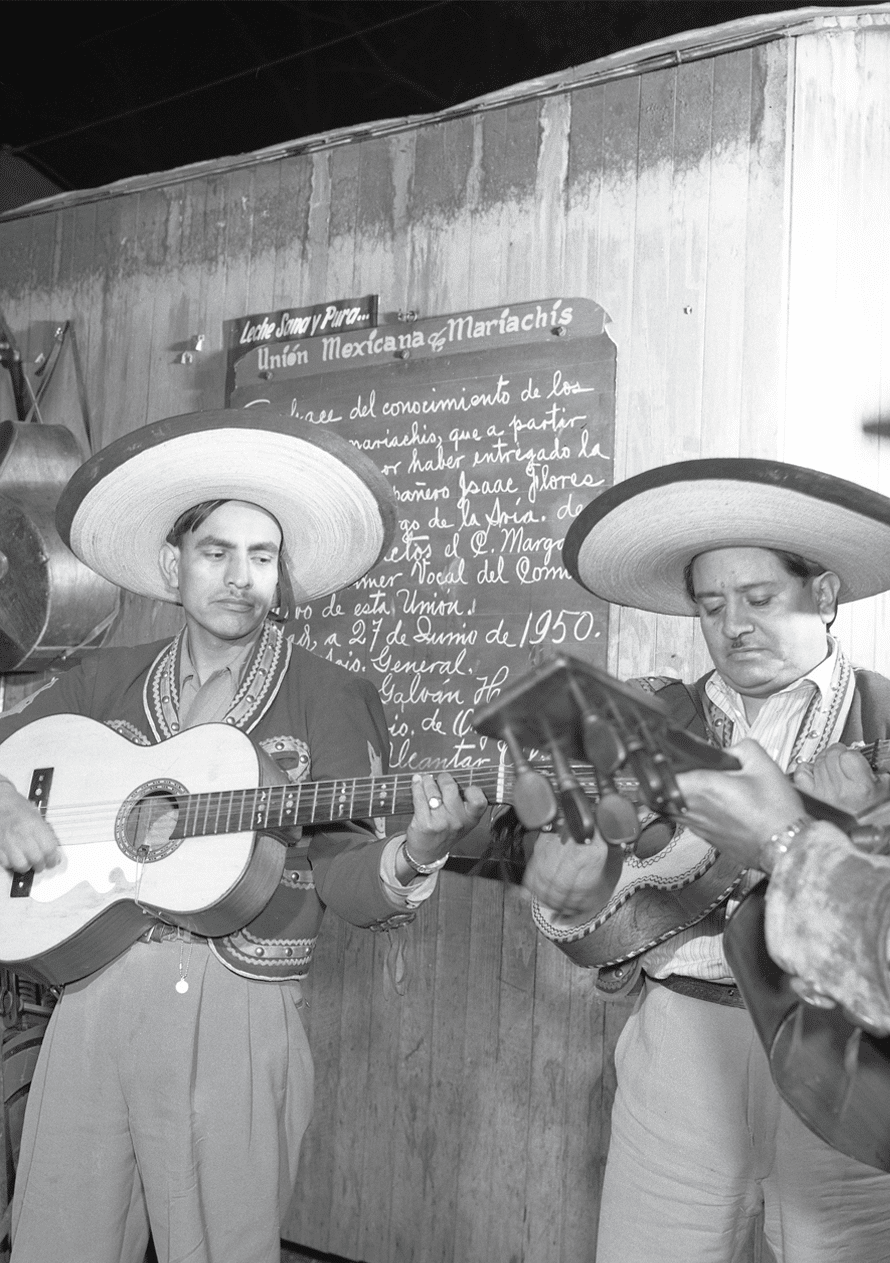

If you ask a foreigner to define Mexico, the answer will surely be that it is the land of tequila and mariachi. Considered Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO since 2011, mariachi is an essential element not only of our musical tradition, but of our culture.

Cocula, Jalisco, is the cradle of this genre that dates back to the viceregal era and mixes indigenous, European and African elements, combining the sounds of the violin, guitar, Mexican guitarron, vihuela, harp and trumpet. The latter is currently the flagship instrument of mariachi, but was not part of the original orchestration.

It was in 1941 when Miguel Martínez became the father of the mariachi trumpet when he first played this instrument with the Mariachi Vargas group in the XEW. Its inclusion was a suggestion of Emilio Azcárraga Vidaurreta, owner of the broadcasting company, in an attempt to face up to the impact of American music, plagued by wind brass instruments.

There are various theories about its name. Some claim that it is of Mayan origin, derived from the word mariamchi, that is, “those who have the same blood”, and another version attributes its origin to the French word mariage, which means “wedding” that began to be used in the 19th century when these groups provided entertainment at these events in the Highlands of Jalisco. Although it is very popular, mariachi history scholars reject the version of the French name because at that time, mariachi music was actually despised by the rancid Mexican aristocracy, which preferred European waltzes.

It all changed in 1936, when the Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán accompanied Lázaro Cárdenas during his presidential campaign tour. This enhanced the image of the mariachi and paved their way to the Golden Age of mexican film. Since then, its music has reached unexpected places, and crossed the language barrier. In Japan, for example, there is the popular Mariachi Samurai that performs songs both in Spanish and Japanese.

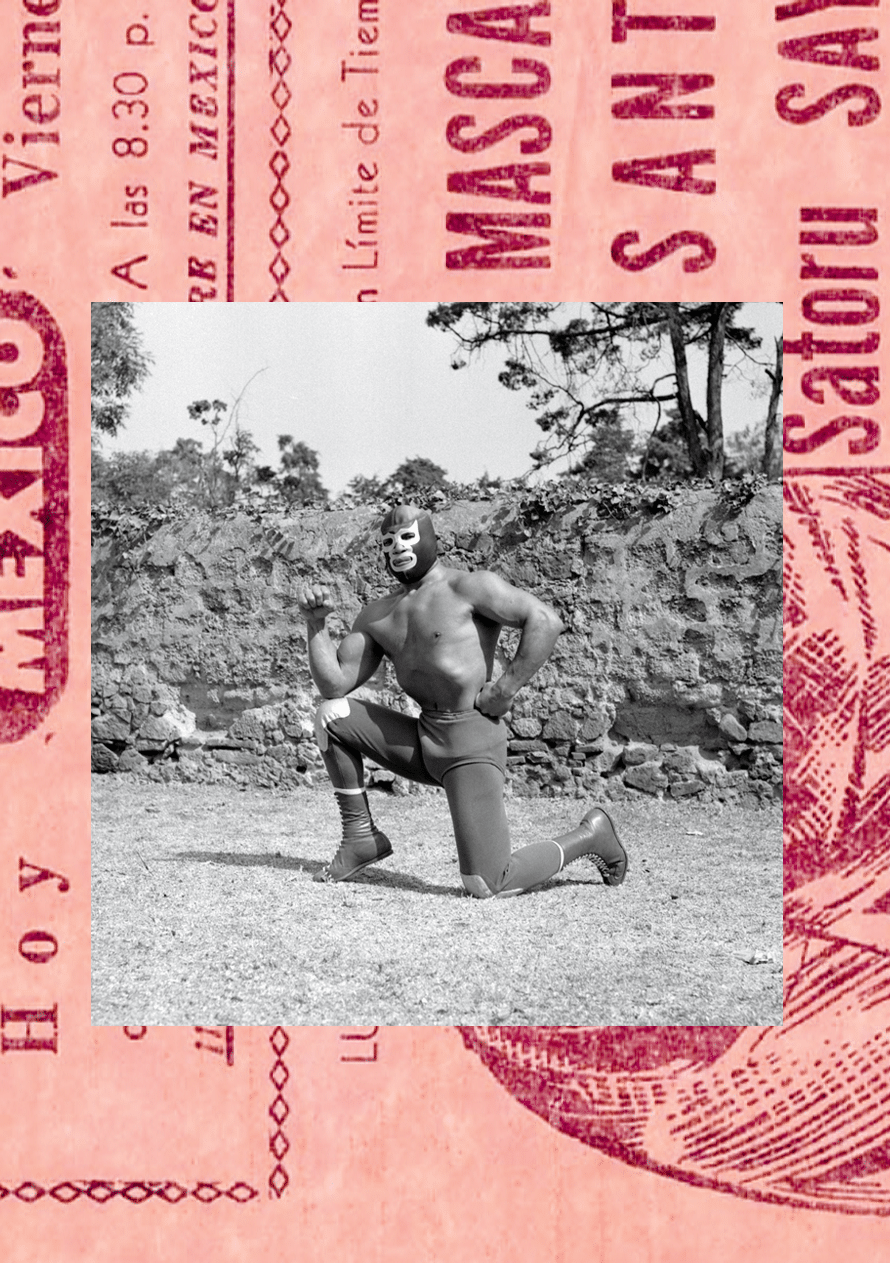

Lucha libre is a version of Olympic wrestling that is practiced in several Latin American countries. However, one of its essential elements is purely Mexican: the mask.

The first wrestler who created a character hiding behind a mask to protect his identity was Ciclón McKey. It was the 1930s and the wrestler went to Antonio H. Martínez, a shoemaker from León who lived in Mexico City, to have him design an accessory that would cover his face. Ciclón McKey appeared in the ring using a four-hole goatskin mask, and he was so successful that he changed his name to “La Maravilla Enmascarada” [Masked Wonder].

The power of the mask captivated the audience and other wrestlers began to use it: Black Shadow, Rayo de Jalisco, Blue Demon and the legendary Santo, “The Silver Masked”, among many others. They were no longer men but legends, whose masks became cultural symbols that have influenced art, film and international advertising.

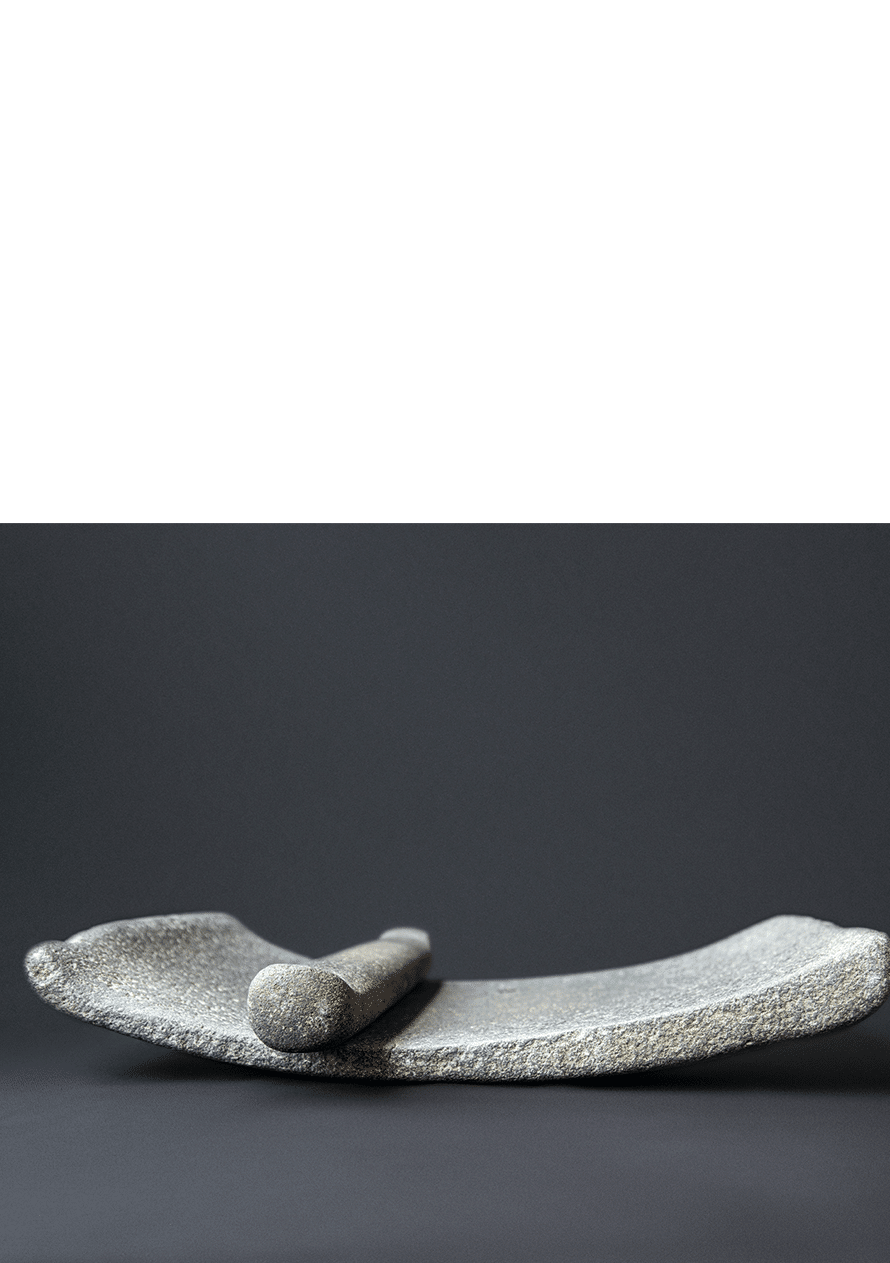

The grinding stone or metate is a traditional utensil made with a rectangular volcanic rock, which is used for grinding ingredients with the help of a cylindrical rock known as metlapil or metate hand. It is believed that its invention promoted the increase in seed consumption in pre-Columbian Mexico, a fact linked to the development of maize domestication.

Its use represents one of the most important gastronomic rituals in the country. Metates are used to grind ingredients, mainly maize and cacao, although it is also used to extract mineral and vegetable pigments.

This plump doll —made of rag, yarn, and colored ribbons that bind its braids or crown its head— is a traditional craft practice, inherited from the Mazahua culture.

Its origin dates back to the time of the Conquest and is located in the region of Michoacán and the State of Mexico. It is believed that its earlier versions included materials such as clay, palm and maize “hairs”. The first name it became known as, was “María”, in honor of the Mazahua artisans who used to sell them on the streets of the Mexican capital.

The legacy of its production is preserved thanks to artisans of Amealco, Querétaro, where it was adopted by the Otomi communities. There it is know as “Lele” and they make her together with “Dönxu”, the traditional Otomi doll.

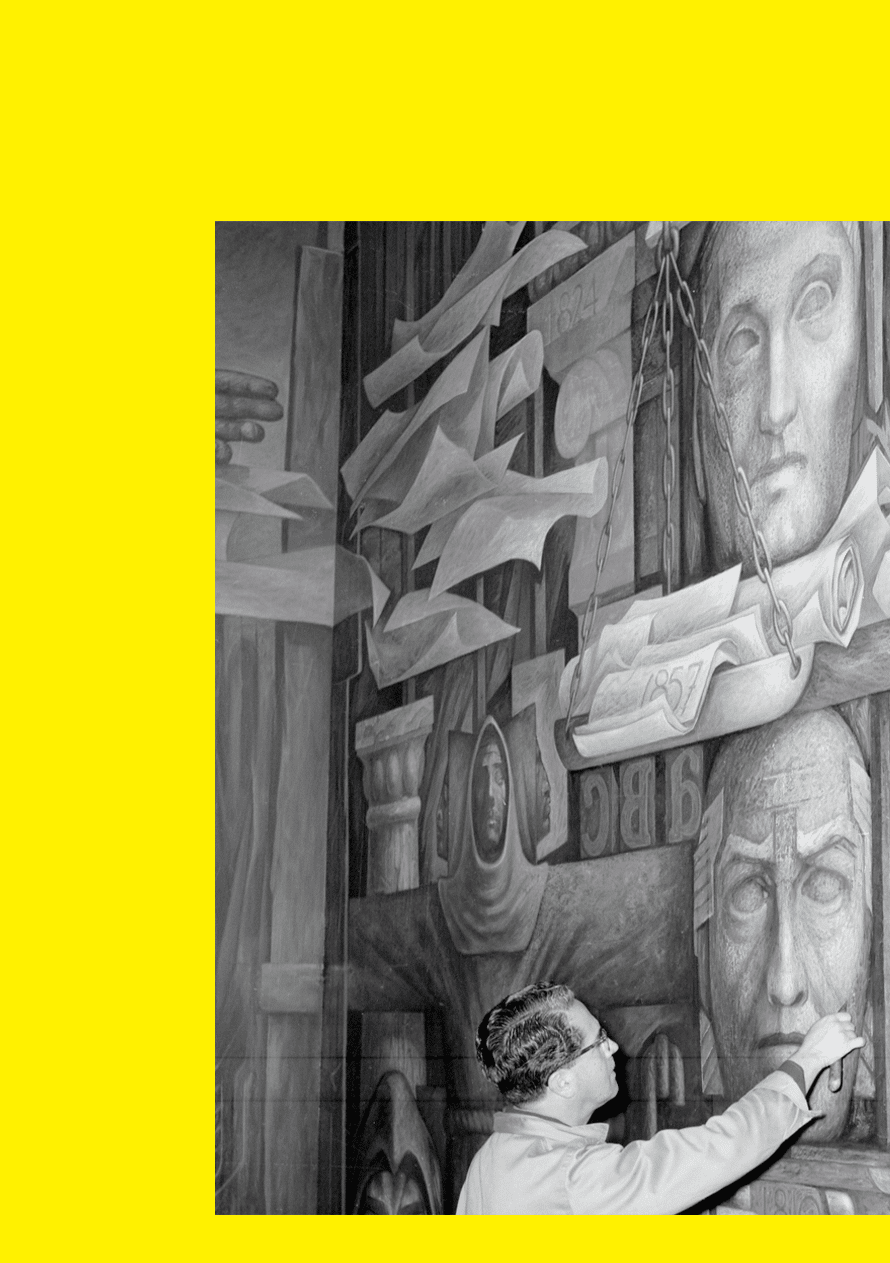

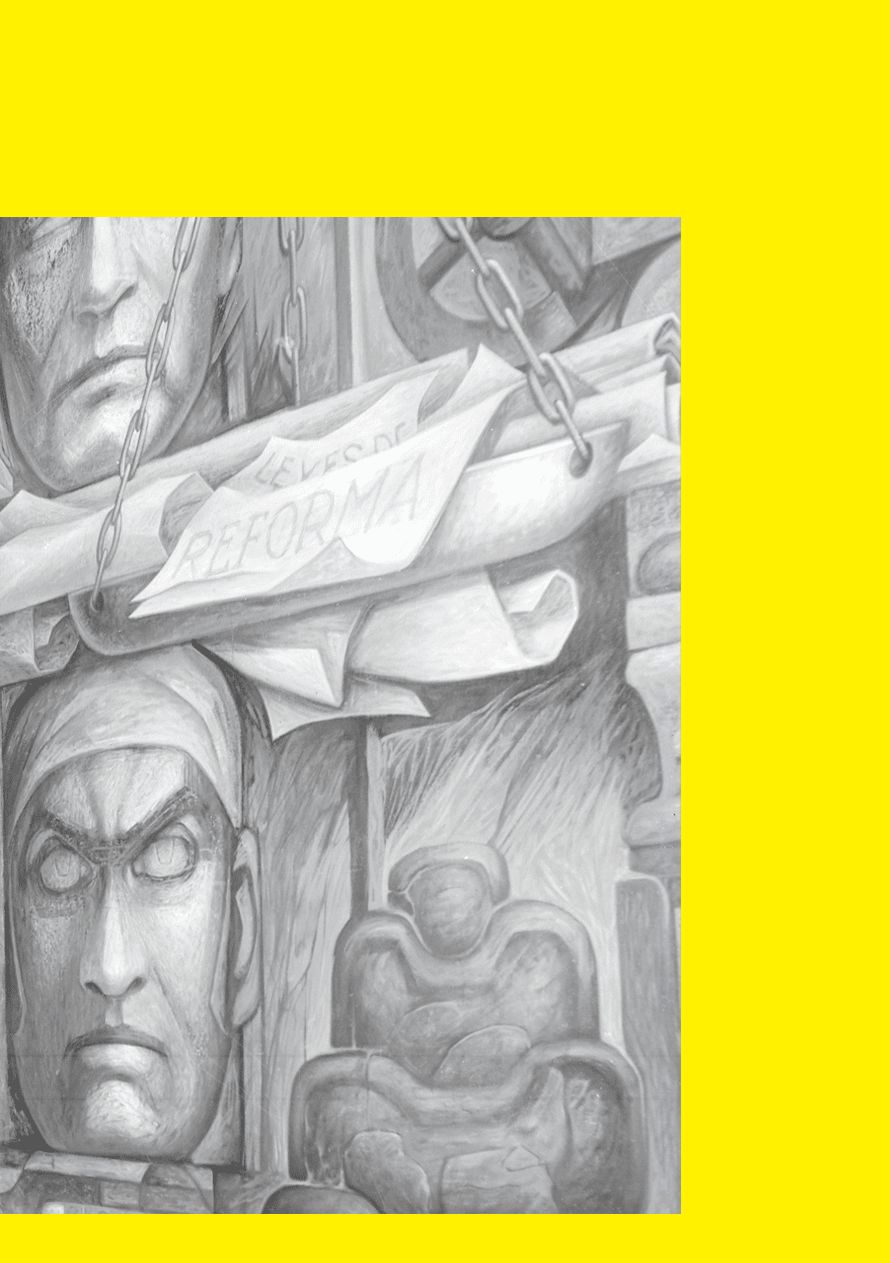

Muralism is a pictorial movement that emerged in the first decades of the 20th century to tell and document the history of the nation after revolutionary events. This aesthetic tradition became the hallmark of Mexican art and its influence extended to countries such as Cuba, Nicaragua, Argentina, Japan, Germany, Italy, Ireland, Spain and Iran, and others that experienced periods of oppression.

Far from European artistic trends, muralists sought to develop their own style, which would reflect national identity through revaluation of indigenous and mestizo roots, and vindicate the political and social function of art, as a resource for ideological propaganda and bring attention to social inequality.

By choosing walls as a medium of expression, Mexican muralists committed themselves to creating a permanent artistic corpus, of public access, made by the people for the people and, therefore, uncollectable.

Thus, artists such as David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, Gerardo Murillo “Dr. Atl”, Rufino Tamayo, Roberto Montenegro, Federico Cantú, Juan O’Gorman, Pablo O’Higgins and Ernesto Ríos Rocha, left an invaluable legacy through their works.

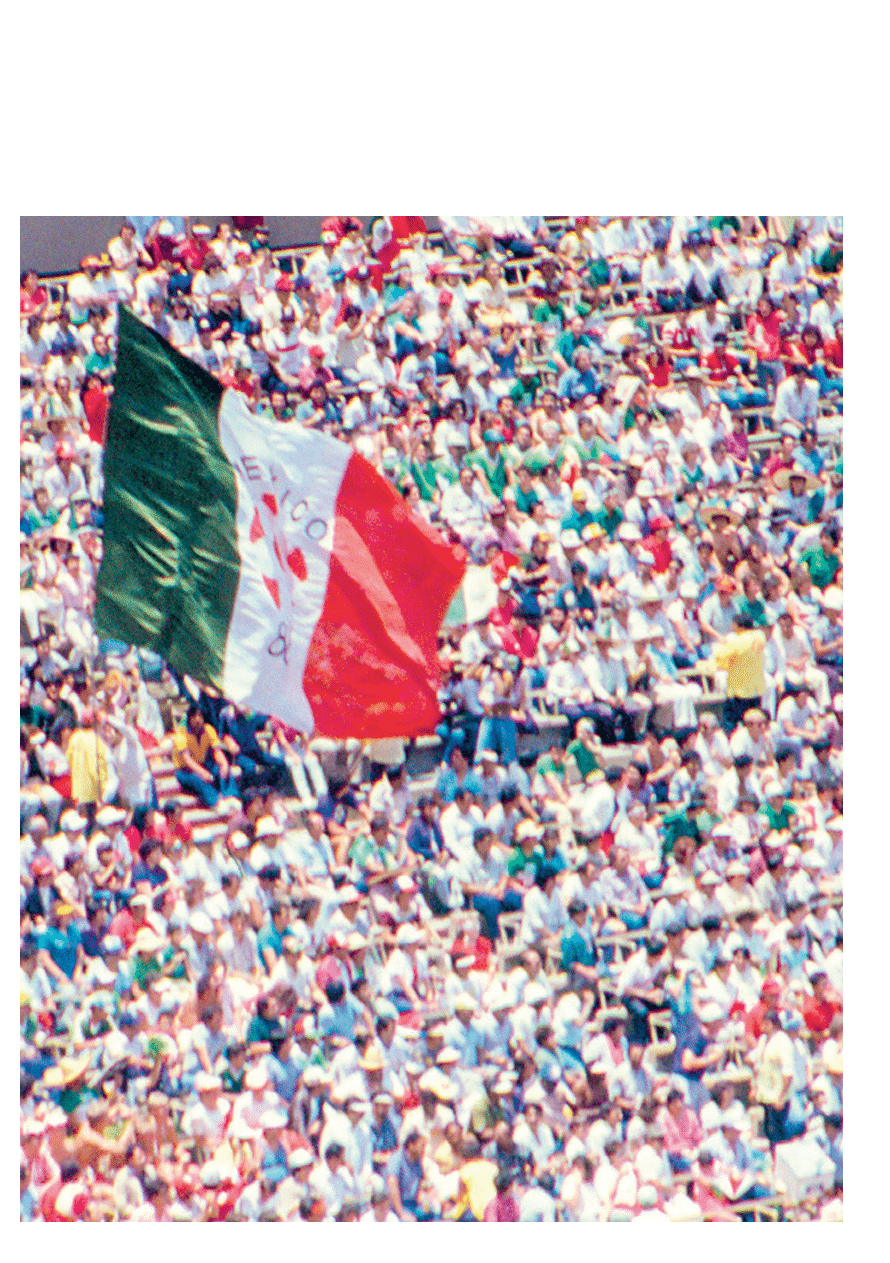

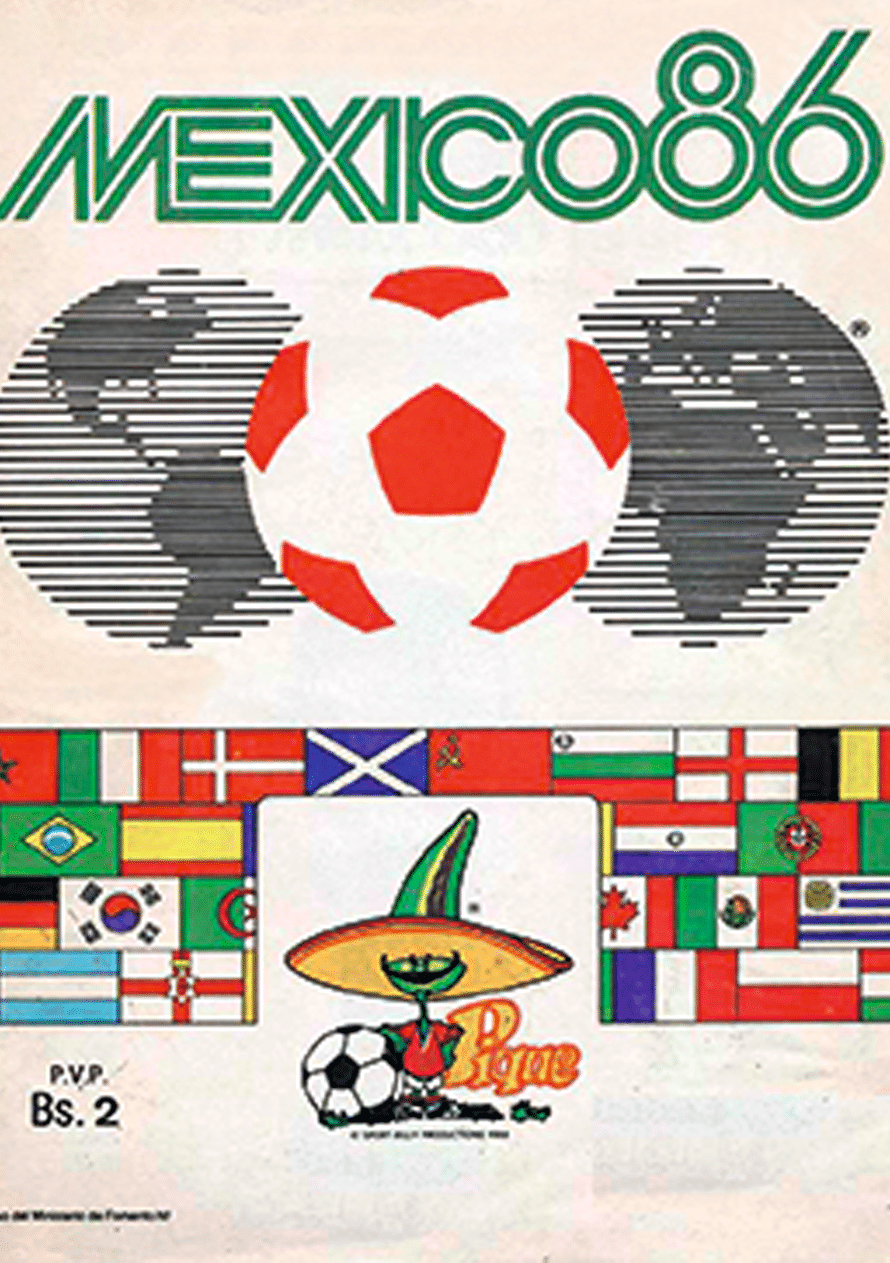

The stadium wave is a coordinated and lively phenomenon that occurs in the stands, among those attending sports or mass events; it is known as “the Mexican wave”, since it rose to fame during a 1986 World Cup game in Mexico. An excited crowd watch-ing a match at the Monterrey University Stadium un-leashed the impulse that triggered the wave, which was seen by millions of spectators.

More than 30 years later, the Mexican wave is a classic celebration that takes place in stadiums around the world and that the Oxford Dictionary defines as “an effect resembling a moving wave produced by successive sections of the crowd in a stadium standing up, raising their arms, lowering them, and sitting down again”.37

With fame came controversy as several countries claimed the invention of the wave. Cheerleader “Krazy” George Henderson proved to have started the first wave of history in Oakland, during a baseball game in 1981. However, he acknowledged “the 1986 World Cup was its great showcase. It was done with every game, and I watched on TV and saw pictures of the impact it had. Stadiums as majestic as the Azteca served as its home. The wave there took on dimensions that I couldn’t imagine in my wildest dreams”.38

Padel is a sport invented by businessman Enrique Corcuera, which is played in pairs with a wooden racket and a ball in a walled-in court.

It was 1969 and Don Enrique decided to adapt a plot of his house in Las Brisas, Acapulco, to play. The land was approximately 20 meters long and 10 meters wide —not big enough for a tennis court— to which he built surrounding walls to prevent vegetation from invading it.

In the middle of that court of unusual features, he placed a tennis net and began to try out a game that he then practiced with a racket and a paddle tennis ball. The sport evolved to have its own rules and elements, and gained popularity among tourists visiting the port. Prince Alfonso of Hohenlohe took it to Costa del Sol in Spain in 1974.

The Padel Pro Tour (PPT) is the most important professional circuit of this sport worldwide. Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Uruguay, Chile, United Kingdom, Spain and Portugal are countries where padel has had a great development. In 1991, the Mexican Padel Federation was founded to promote this sport in the country.

Mexico is a country of celebration and color. The calendar has countless dates in which each state enhances its traditions through dance, handicrafts, gastronomy and ceremonies in honor of some saint, a sacred food or simply for the joy of life or death.

From Baja California to Quintana Roo one could take a tour of the folklore of Mexican festivities. In 2010 one of these celebrations was inscribed in the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity: the Parachicos.

Known as the Fiesta grande of Chiapa de Corzo, in Chiapas, this celebration is held during January and is dedicated to Our Lord of Esquipulas, Saint Anthony Abbot and Saint Sebastian. One of its most representative manifestations are the dances of the Parachicos, considered a communal offering to the venerated saints.

The dancers wearing serapes, embroidered shawls, multicolored ribbons and a fiber headdress, hide behind carved cedar wood masks —whose features resemble those of the Spaniards of the time of the Colony— and go along the streets carrying holy images, while playing tin maracas called chinchines. They are led by a character that carries a guitar and flute and, accompanied by drummers, sings prayers that are answered by the Parachicos.

The chants, costumes and the mask-making technique survive having been passed from generation to generation, for over 300 years.

Pearl trade in Mexico dates from the pre-Columbian era. Maya and Aztec merchants roamed the limits of their empires in search of these gems with which they made jewels to honor royalty and the gods.

In 1535, Hernán Cortés embarked in search of the treasures of the New World and found a source of wealth, known since then as the “Sea of Cortez”. In these waters the “black pearl” was formed and soon became the star product of Mexican export known as the “Queen among gems, the gem of queens”, since its use became fashionable among European nobility. This reign lasted until the end of the 19th century, when pearls almost became extinct due to overfishing. They survived thanks to Gastón Vives, creator of the first oyster farm in the world that worked successfully from 1902 to 1914.

It took several decades for the revival of pearler activity in the Gulf of California, which happened in 1993 spearheaded by Enrique Arizmendi, Manuel Nava and Douglas McLaurin Moreno, creators of an aquaculture project in which the species Pteria sterna was cultivated, and thanks to which Mexican pearl farming has resumed its position as one of the most exclusive productions in the world.

The origins of the traditional Mexican piñata date back to the 17th century when Franciscan missionaries arrived in the New World from Spain. This Order can be traced to the town of Assisi, in Italy, where expeditionary Marco Polo brought a paper colored object from his many trips to China in the 13th century.

There are indications that the ancient Aztecs had a custom for which they adorned hollow clay figures with feathers, and filled them with beads to honor the god Huitzilopochtli. That container along with some games practiced by the Maya represented the perfect opportunity to create an evangelistic resource.

The clay figure became a pot covered with colored paper —a reflection of world’s vanity— of which seven points came out, each one representing a deadly sin. These temptations are overcome with the blows of a stick that represent the force with which faith and obedience defeat evil.

Once envy, sloth, gluttony, wrath, lust, pride and greed are overthrown, a shower of rewards falls on the believer, who performed this battle blindfolded, representing the blind faith in God. The piñata ritual became an essential part of posadas during Christmas celebrations in Mexico.

With the passage of time, Mexican piñata makers evolved the papier-mâché technique until they turned piñatas into an object of the most varied forms used in all kinds of celebrations and irrevocably alluding to Mexican culture.

Pirekua is a traditional type of music among the P’urhépecha indigenous communities of the state of Michoacán. In 2015, it was inscribed in UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage List.

This genre arose from the syncretism of music and religious chants of Spanish evangelizers and pre-Hispanic songs and African influences, inheritted from the slaves who arrived to Mexico from those lands.

Pirekua means “song” in the P’urhépecha language and can be performed in a solo, duet, trio, choir and orchestra, by both men and women who are known as pirériechas. Traditionally it is sung in native language, but there are some pieces in Spanish and others are instrumental.

Pirériechas are very respected, since they are social mediators using songs to express sentiments and communicate events of importance to the communities. Songs and techniques are passed from generation to generation and constitute a pillar within their traditions.

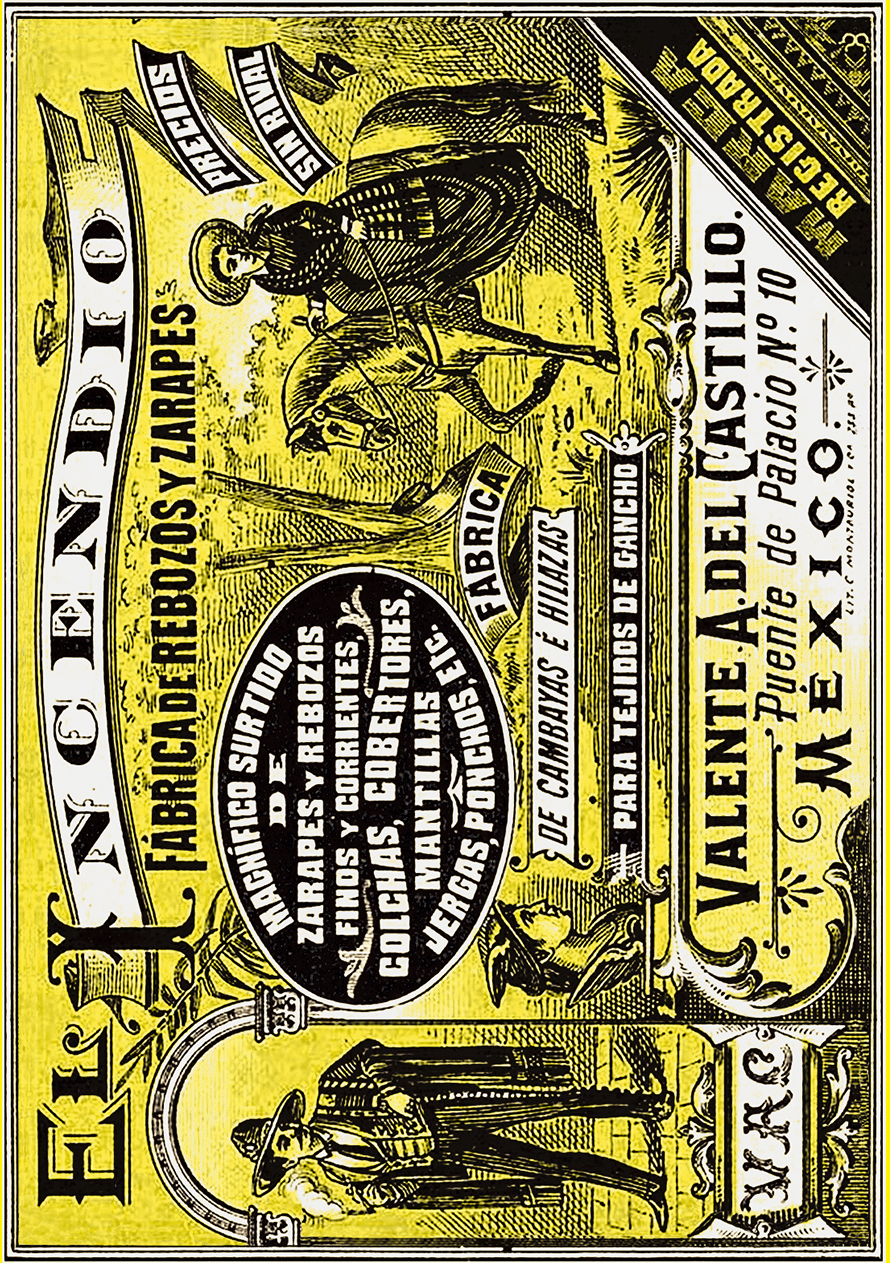

This traditional mestizo garment —originally for men’s use— blends in its warp the Mesoamerican textile tradition with European fabric. Although there is no exact data on its origin, it is believed that it is an evolution of the blanket known as tilma, used by the natives, merged with the Andalusian and Valencian capes brought by the Spaniards in the 16th century.

This garment is made in various regions of the country, where it is known by names such as: tilma, gabán, chamarro, jorongo, cotón, cobija and frazada. But the classic serape, symbolic of the country, is the one made by artisans in Saltillo, Coahuila.

In the last century, it was an inseparable garment of pawns, horsemen, charros and village people. In the 19th century it was used by insurgents, chinacos and bandits known as Los Plateados.

The serape from Saltillo is hand-woven on a treadle loom, with wool dyed with natural colors. The classic design has a degradation of eight shades of colors, which they call “shadows” —inspired by the sunrises or sunsets of the town— combined with a fringe, and the figure of a diamond at the center, symbolizing wealth.

The Acapulco chair is one of the most renowned designs of the 20th century. It was created by artisans of the port that gave the chair its name in the 1950s, back in the day when Acapulco was the favorite refuge of great Hollywood stars.

It consists of an iron frame over which rubber cords in various bright colors are interwoven entirely by hand, resulting in a concave and comfortable seat, whose weave allows the wind to pass through its crevices, counteracting the summer heat.

Its simple and peculiar style has generated countless versions, the most popular is the “Hornitos”, small and oval; but there is also the “Condesa” design, with armrests; the “Pichilingue”, with a more rounded back and similar to a small bench; and the “Hornos” type, large and oval. They were all named in honor of Acapulco beaches.

Its use has extended to reach beach destinations in the United States, South America, Asia and Europe, where they even present it as the “Ibiza chair”, but one must not confuse the port; this design is entirely Mexican.

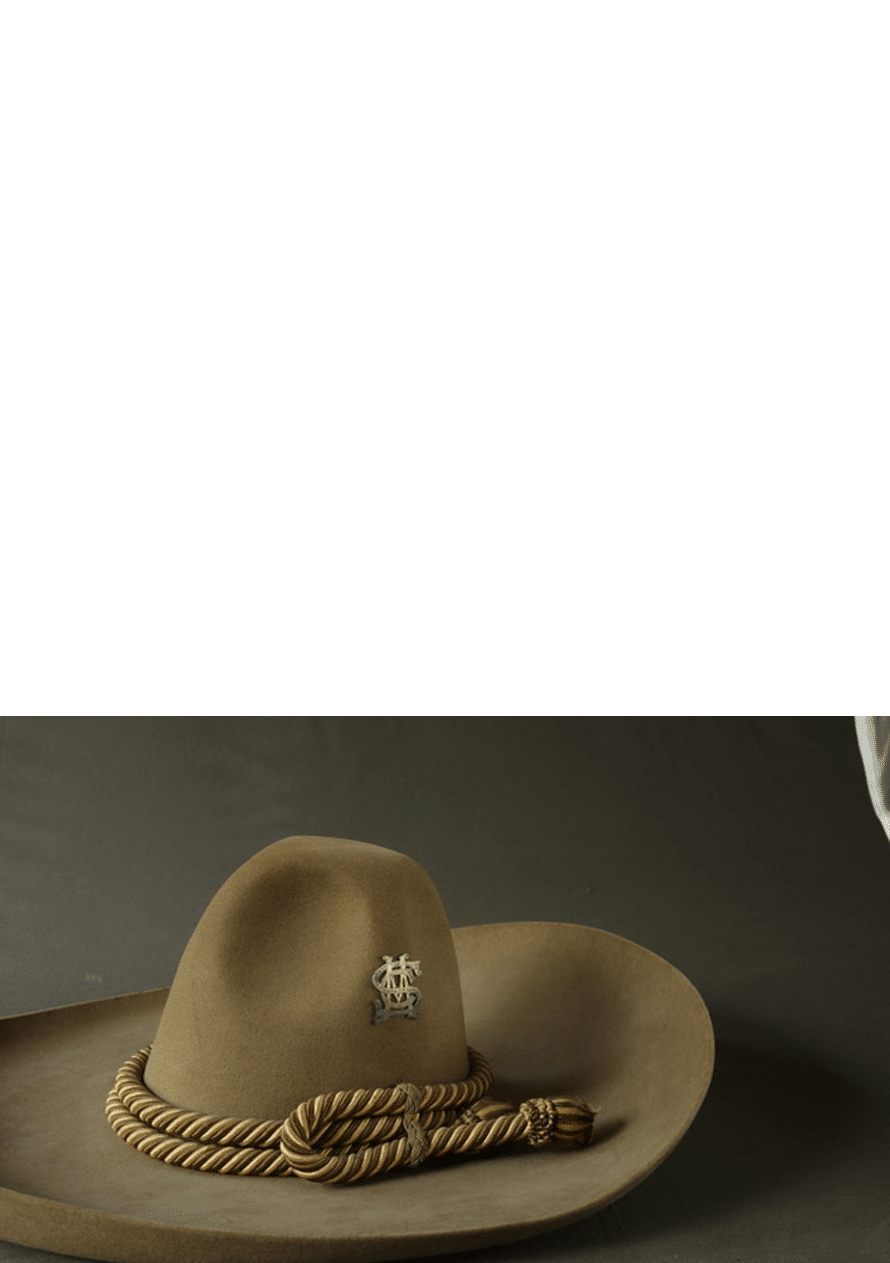

The charro hat and suit are emblems that define our country’s identity. In 1931, former president Pascual Ortiz Rubio decreed that the charro suit would be the official attire and a symbol of our nationality.

The origin of this mestizo garment dates back to colonial times with the appearance of chinacos, horsemen dedicated to farming tasks, who later became famous for their bravery when they aided the army, first in the War of Reform —Maximilian of Habsburg is credited with the modification of charro trousers at this stage— and later against the French intervention in Mexico.

Gradually the charro image gained popularity thanks to the characters of the Golden Age films where they would always appear dressed in a wide-brimmed hat, trousers with chaps and a jacket with attractive buttons.

In 1936, when Lázaro Cárdenas was accompanied by mariachis on his presidential campaign tour, he demanded that they wear the national attire and thereafter both symbols became intertwined.

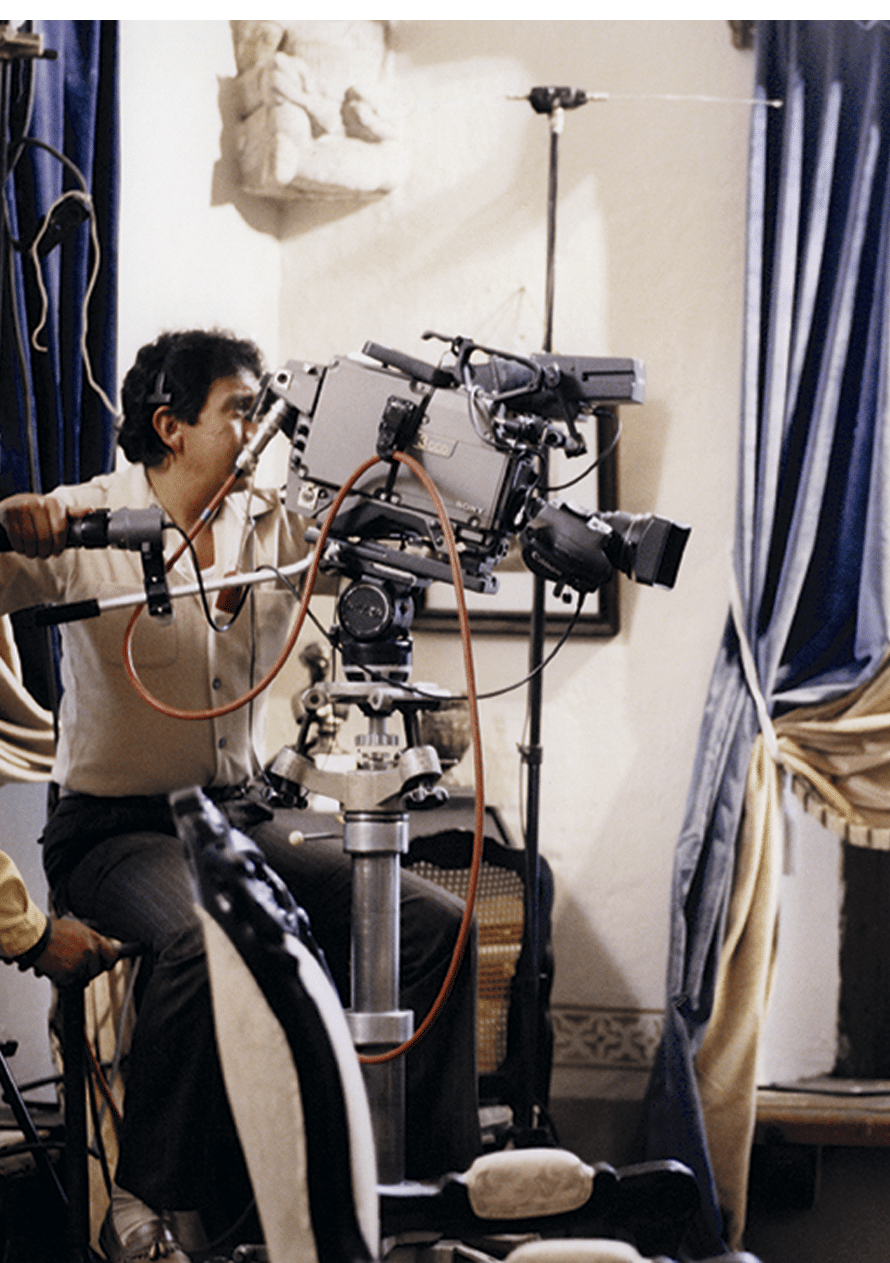

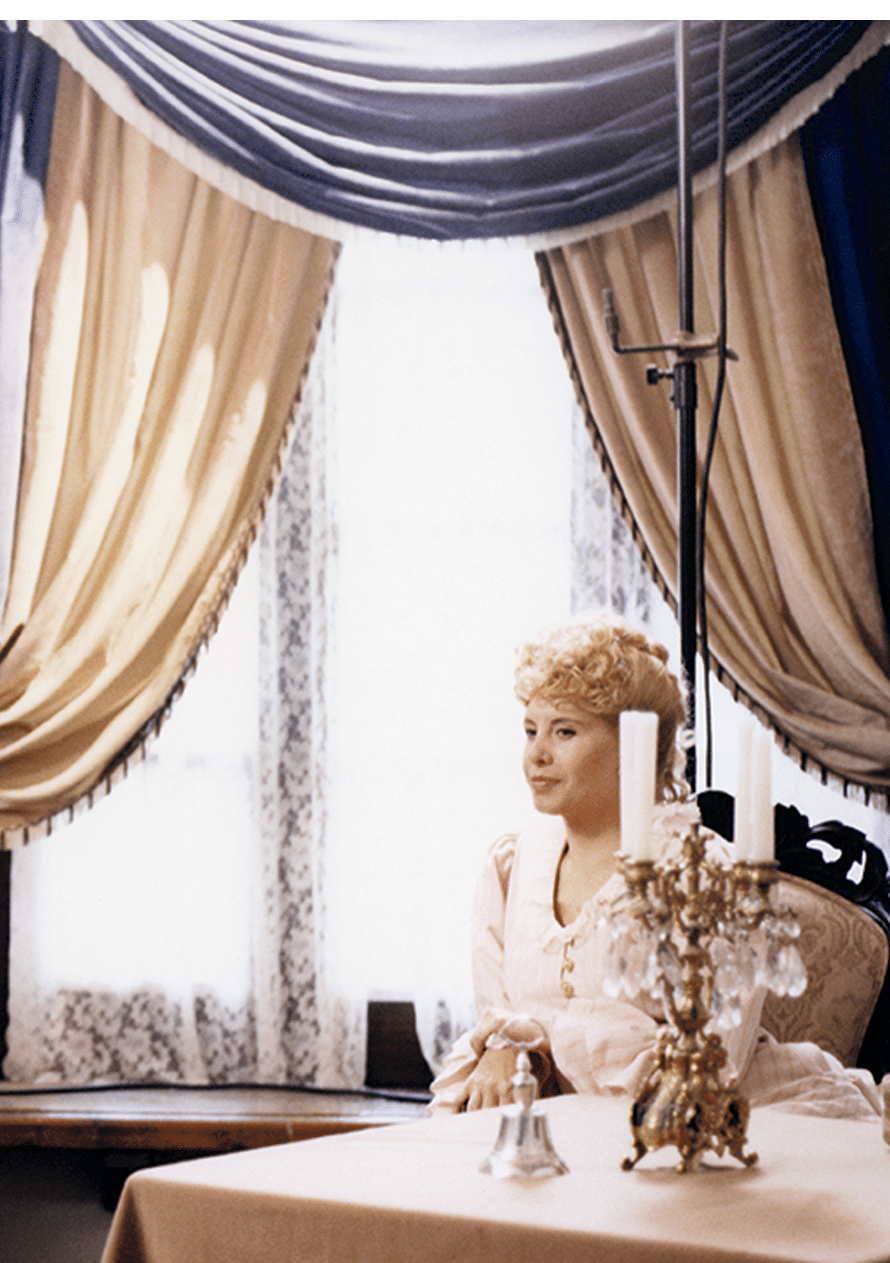

The origin of this television genre dates back to the French feuilleton serial stories of the 19th century, which resulted in romantic comedy and later found voice and musical background in the radio soap operas. When the use of television became popular, the stories searched for a space within the small screen.

The first prototype of a weekly serial plot on television, with the romantic halo of European feuilletons, was created in Cuba in 1951. That same year, “Ángeles de la calle” was released in Mexico. The format we know today did not begin until 1958, the year in which “Senda prohibida” was broadcasted in our country.

The global reach of these serials took place in 1978, when “Los ricos también lloran” was taken to Russia, China, the United States and the Middle East. It was so successful that its protagonist, Verónica Castro, was appointed Ambassador of Peace in Russia, and soap operas became the most exported product by media company Televisa, forefather of the genre.

The melodramas’ route garnered audiences in the most unexpected places and their protagonists —such as Victoria Ruffo, Edith González and Thalía— were received as heroines both in Turkey and Uzbekistan, the Philippines, Armenia and Indonesia. The impact of soap operas has been the subject of countless analyzes and criticisms, but it has also been explored as a teaching resource.

In 1984, Miguel Sabido, creator of the educational soap opera, received an invitation from Indira Gandhi to develop in India a plot that promoted harmony between castes and a critique of arranged marriages in this country. Thanks to UNESCO, these types of productions known as the “Sabido model” enjoyed great success in countries such as Ethiopia, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Malawi, Burkina-Faso, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sudan and Swaziland, providing information on topics such as family planning and gender equity.

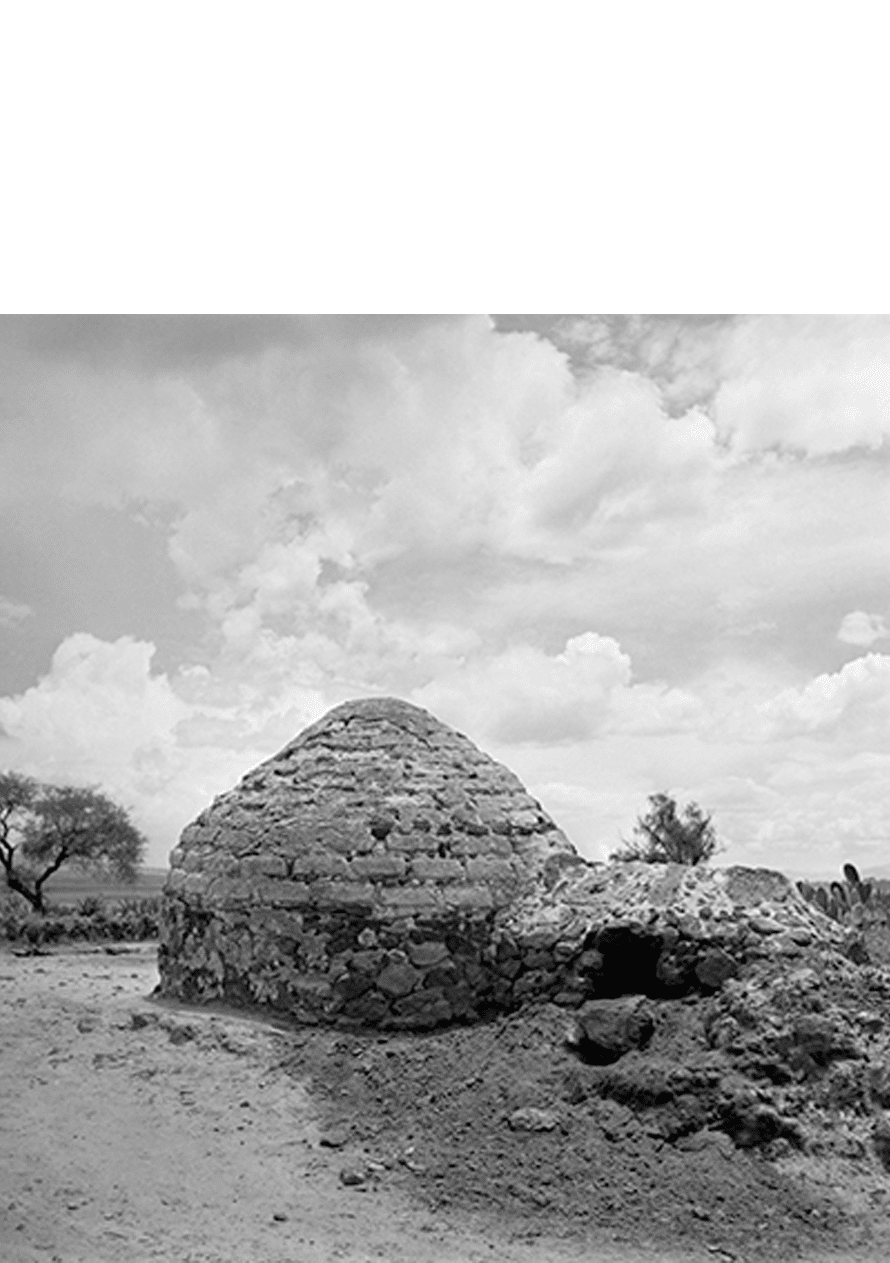

The word temazcal comes from the Nahuatl temazcalli, which means “bath house”. It is a powerful pre-Hispanic steam bath, based on hot volcanic stones and healing plants, which is used for therapeutic, hygienic and ritual purposes.

According to Aztec cosmogony, the temazcal tradition symbolizes a reconnection with the mother’s womb, a place for cleansing and rebirth, protected by Temazcaltoci —mother of the gods, grandmother of Earth— so it not only purifies the body but also the soul. Despite the efforts of the Spanish conquerors to eradicate it, the temazcal practice is still in force and is attracting more and more adepts.

Benefits of this millenary technique include ac-celeration of the healing process, especially injuries, broken bones, contusions and skin problems, as it stimulates skin renewal. It also helps fight the flu, bronchitis, asthma, sinusitis and other diseases, in combination with medicinal plants; also, traditional midwives use it to prevent pregnancy discomfort, and during delivery and postpartum care.

Mexican textile tradition is not only a lively and constantly changing artisanal practice, but it also represents a language through which our ancestral cultures show their identity and immortalize their customs and cosmogony.

In all indigenous communities of the country there are textile artists, weavers and embroiderers who have protected techniques and symbolisms. As has been stated by the Museum of Popular Art these “miraculous hands turn needs and fears into spirit, popular works of art arising from the biodiversity that comprises their natural habitat”.

The wealth of this heritage begins with the pre-paration and dyeing of fibers and threads with natural pigments, and it culminates with designs and the execution.

In Oaxaca this wisdom is preserved in the hands of the Mazatec, the Chinanteco, the Mixes and the Zapotec peoples. The latter, inhabitants of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, work one of the most well-known embroideries in the world over dark velvet garments: large colorful flowers and a border of pleated silk on the edge of the skirt, known as the Tehuana costume. Other communities are the Maya, in Yucatán; the Purepecha and Otomi, in Michoacán; the Teneek (or Huastec), in San Luis Potosí; the Totonac, in Veracruz; the Mazahua, in the State of Mexico; the Amuzgo, in Guerrero; the Tzotzil, Tzeltal and Zoque, in Chiapas; the Rarámuri-Tarahumara, in Chihuahua; and the Huichol-Wixarikari, in Nayarit.

The beauty of the artisanal textile work of these cultures is so great that, unfortunately, there have been multiple cases in which international designers and companies simply appropriate these designs and market them without acknowledging their cultural importance and the sometimes sacred character of this iconography.

Poet Carlos Pellicer stated that “Mexican people have two obsessions: a liking for death and a love of flowers”. There is a date in the spiritual calendar of Mexicans in which these two elements concur: the Day of the Dead.

It is a celebration without comparison that has its roots in the commemoration of mortuary rituals of pre-Hispanic times in syncretism with the Catholic religious rituals brought by the Spaniards.

In the indigenous worldview it involves a transitory return of souls, who return home to the world of the living to spend time with family members and feed on the essence of food offered to them on altars placed in their honor.

The souls that come back to Earth are guided by mexican marigold petals —especially Mexican marigolds— that families place next to candles and offerings along a path that goes from the cemetery to their house. The deceased’s favorite dishes are carefully prepared and placed around the family altar and grave, amongst flowers, cut tissue paper, sugar skulls and incense smokers burning copal.

In its most authentic expression, it is an intimate act, a rite of domestic simplicity and deep love for those absent, who not in vain are called the faithful departed. Even in the humblest home, the ceremonial act of liberating the family table from its daily use is fulfilled and, for a short time, turned into an altar, decorated with cut tissue paper of the most festive colors. Mole is prepared, as well as pulque, sweets and bread that the dead person being honored enjoyed the most in life, and whose portraits preside over the celebration.

This tradition, passed on from generation to generation, acquires different dimensions according to the community in which it is carried out. In the Maya, Nahua, Zapotec or Mixtec regions this celebration has great relevance. Touching, mysterious, cheerful, ancestral and unique, our Day of the Dead is today a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

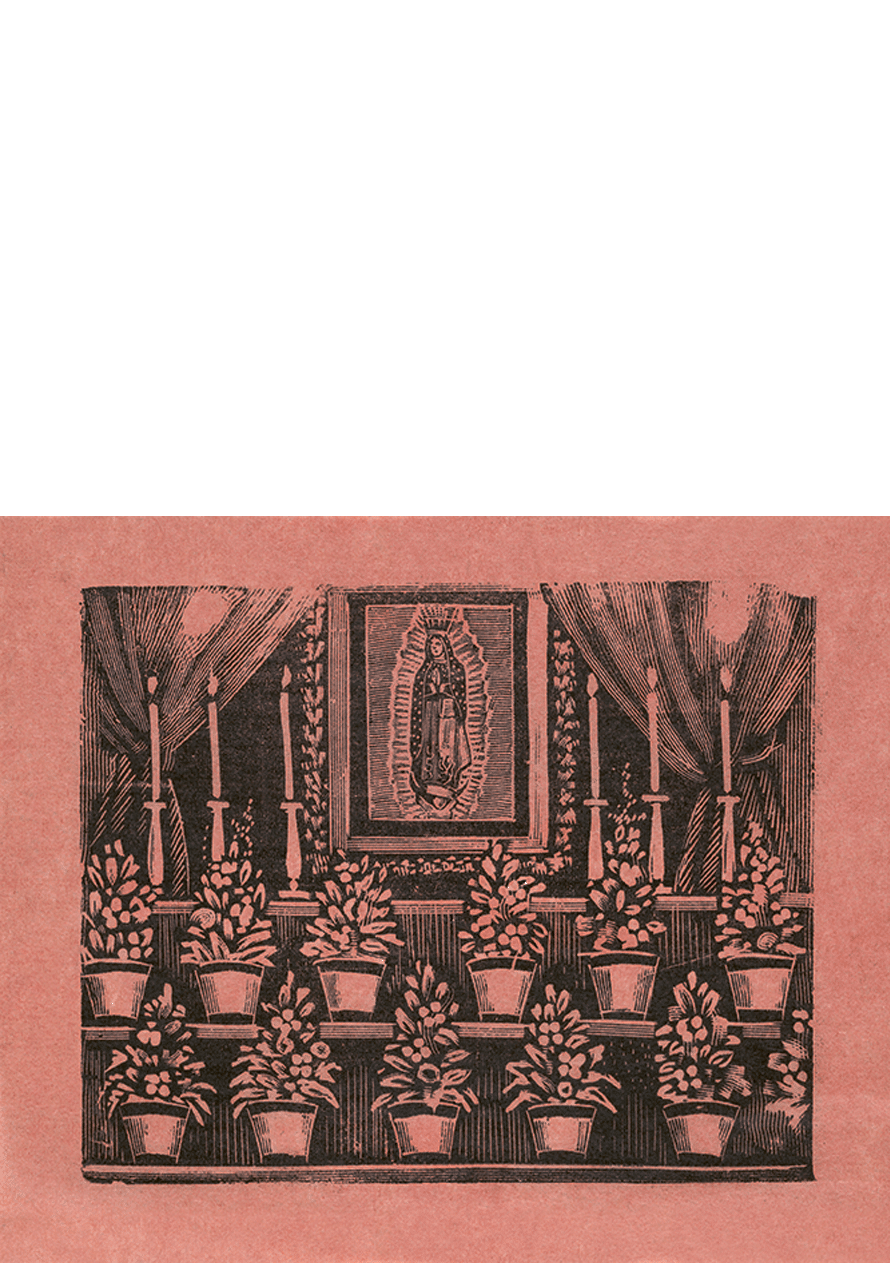

According to the Catholic faith, the dark-skinned Virgin appeared on the Tepeyac Hill before Juan Diego on four occasions. On the last one she asked him to visit Friar Juan de Zumárraga and left her image imprinted on his tilma or cloak in which the indigenous man carried flowers to offer to the first bishop of Mexico.

The story of these events was recorded on the Nican Mopohua, a document originally written in Nahuatl in 1556, currently protected in the New York Public Library.

But beyond religious belief, the dark-skinned Virgin, known today as the Virgin of Guadalupe, became a national symbol, linked to Mexico from its most intimate roots. From colonial times, passing through independent Mexico until our present time, she has been the banner of the army that sought the country’s independence, a miracle doer and an omnipresent image in Mexican homes.

In 1737, the Virgin of Guadalupe was proclaimed as patron of Mexico and December 12 was established as a holy day and national holiday. In 1754, pope Benedict XIV appointed her patron of New Spain —from Arizona to Costa Rica— and in 1945 pope Pius XII named her Empress of the Americas.

Although the Basilica in Mexico City is the main center of guadalupana devotion, receiving approximately six million pilgrims from all over the country and abroad every December 12, the Virgin’s image is also venerated in many churches, cathedrals and chapels around the world, including St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York and Notre-Dame in Paris.

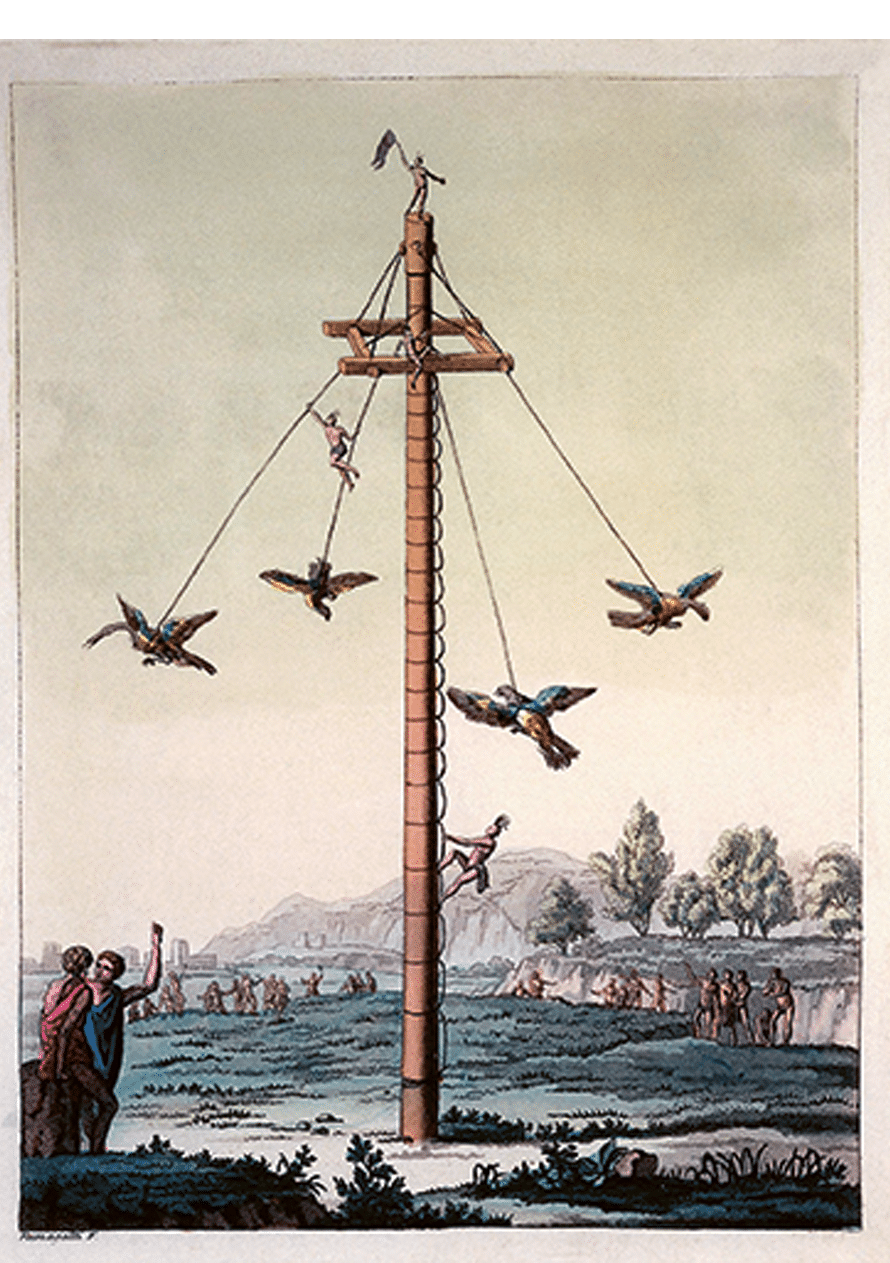

The Papantla Flyers ritual ceremony of pre-Hispanic origin is performmed by the Totonacs, Teenek, Nahuas, Ñañhus and Maya. With this fertiliy dance they seek to communicate with their gods and revive the myth of the universe. It conveys their cosmogony and community values.

During the ceremony, four young men climb up a pole of 18 to 40 meters high, made from the trunk of a tree recently cut in the forest —after having begged for forgiveness to the mountain god. A fifth man sits on the platform on the top of the pole, who is known as “the foreman” and plays melodies in honor of the Sun with a flute and drum.

After invoking the king star and all the elements, the four dancers fling themselves into the void from the platform, to which they are tied with long ropes that unroll as they rotate imitating the circular flight of birds, and gradually descend until they reach the ground.

The representative and emblematic value of this dance is most evident in the region of Totonacapan, in the state of Veracruz. There, over 500 flyers have been identified, distributed in different groups —more than 30 officially registered—. Nowadays there are three schools that teach children the ritual in its original form, along with the profound value of its meaning. In 2009 it was inscribed on the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.