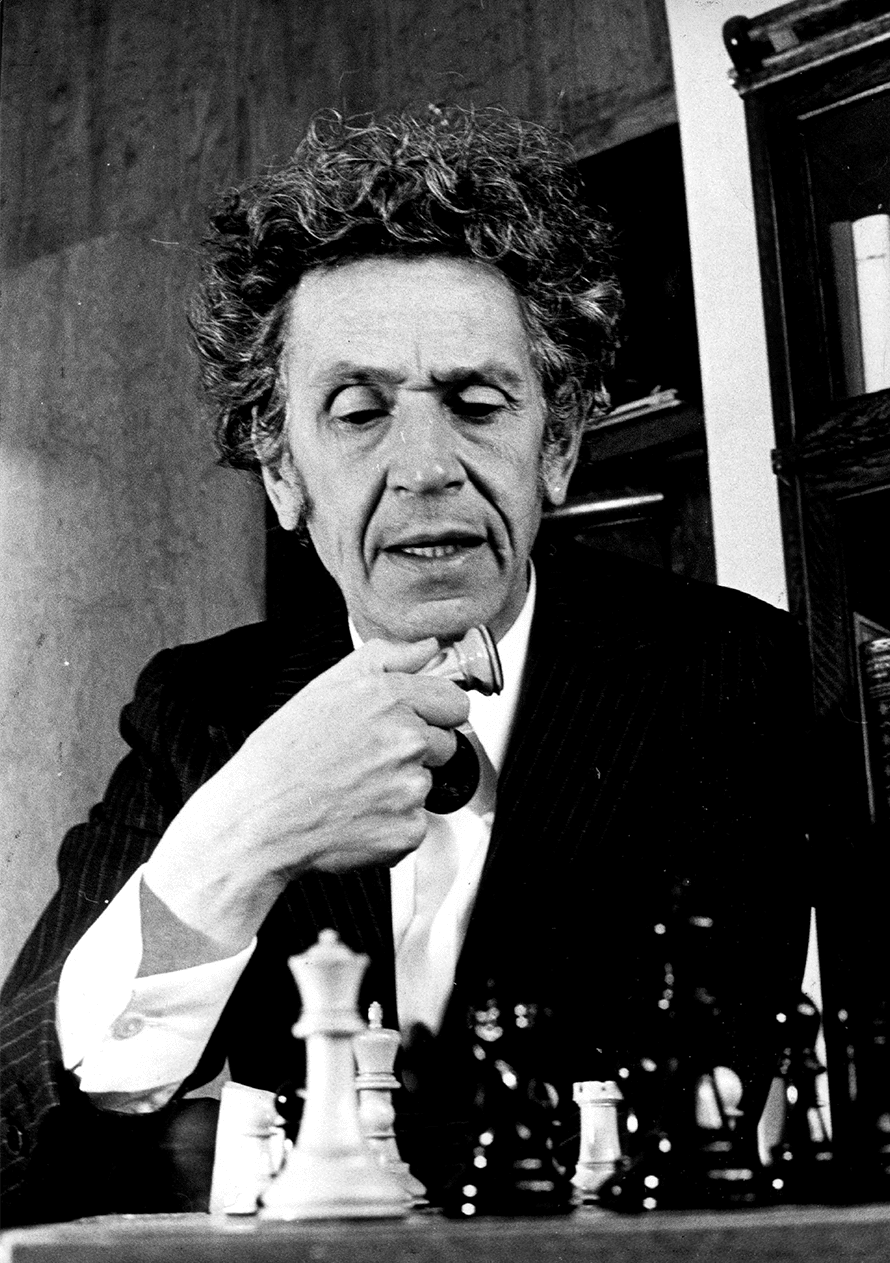

Legend has it that Juan José Arreola (1918-2001) was born with the gift of gab. In his village, Zapotlán El Grande, Jalisco, he was famous for being a reciter who from an early age assumed his passion for language.

Because of the Cristero War, which closed schools run by churches, he had to abandon formal studies and self-taught himself. When he turned 17, he left Zapotlán to go to Mexico City where he studied theatre.

His book Varia invención, published in 1949, placed him in the scene of Mexican literature. This stylistic exercise combining prose and poetry in different voices caught the attention of writer Jorge Luis Borges, who asked to meet the author in one of his visits to Mexico.

According to the Colombian critic Fabio Jurado: “Borges was the first to acknowledge Juan José Arreola as the author who was already revolutionizing and innovating Latin American narrative. That link with Borges makes us perceive in Arreola a presence of universal literature”.[ref id="4"]

To speak of Juan José Arreola is to encompass a universe that combined histrionism with the written word, play, wit, laughter, memory and tradition. He is an essential writer in the history of our country’s literature and a reference that left a mark in the world of cultural television, entertainment and dissemination of culture.

José Antonio Alzate y Ramírez (Ozumba, State of Mexico, 1737-1799) was one of the most distinguished polymaths of his time who invented, in 1790, the “floating automatic shutter”, better known as ballcock.

At the end of the 17th century water waste represented a serious problem for Mexico City, due to the large quantities that spilled out from fountains because they did not have a system that would close them when full. The solution was this simple device that controls the exit of liquid from a container to avoid its waste. Its most common use is in toilet systems and water tanks. It has saved millions of liters of water.

To pay homage to its inventor, for this and many other contributions in various fields, the Antonio Alzate Scientific Society was founded in 1884, which later became the National Academy of Sciences.

There are many creators —from all periods and artistic disciplines— whose names have been inextricably linked to one of his works, to the iconic piece of his legacy. That is the case of José Gorostiza (Villahermosa, Tabasco, 1901-Mexico City, 1973) and his inexhaustible poem Death Without End, considered an essential composition of literature in Castilian language.

Death Without End was published in 1939 and had an immediate impact on the world of literature, where it was described as “one of the greatest achievements of contemporary poetry”. It is an extensive work, consisting of ten parts where he pours the distress of the individual being in a song of philosophical searches, dedicated equally to existence and to destruction. Its complexity, which continues to be the subject of extensive studies, lies in the fact that it functions at multiple levels, which the poet elaborated with the idea, he said, of “doing something as someone constructing a building, with the criteria of an architect or as the composer who intends to create a symphony”.

Gorostiza belongs to the generation of the Contemporaries, a legion of poets and critics essential for the development of Mexican literature in the 20th century, an example of the “New Mexicans” convinced that Mexicanness was not at odds with universality.

Fernando Savater once claimed that José Alfredo Jiménez was “the best poet in Mexico, with the forgiveness of Octavio Paz”,[ref id="27"] and clarified that the phrase was not his but of French writer Jean-Paul Sartre, who once sang Jiménez’s verses “Vámonos, donde nadie nos juzgue...” to Paz, with all the pain in his heart.

José Alfredo Jiménez (Dolores Hidalgo, Guanajuato, 1926-Mexico City, 1973) has gone down in history as “the poet of desolation”. For decades, his lyrics have accompanied broken hearts, those who suffer, those in love and those who, despite marginalization, continue to sing, still convinced that “life is worth nothing”.

The lyrics of “Hijo del pueblo” renewed the ranchera genre and his 280 songs make up a living and eternal heritage that spreads in the echoes of mariachis, whether in Garibaldi or in any corner of the world where the chords of “El rey”, “En el último trago”, “Si nos dejan”, “Que te vaya bonito” or “Un mundo raro” are heard.

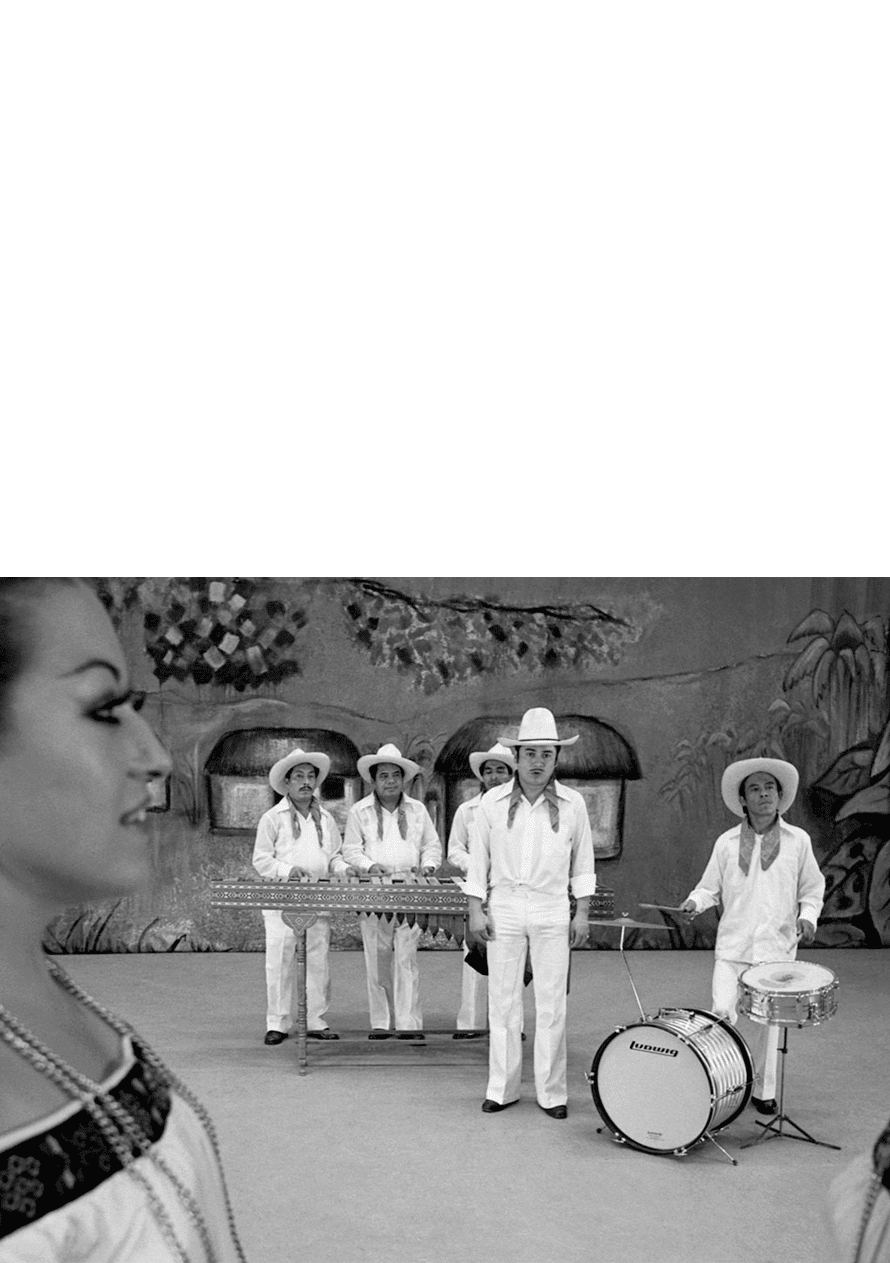

José Pablo Moncayo García (Guadalajara, Jalisco, 1912–Mexico City, 1958) is one of the most important representatives of Mexican musical nationalism of the 20th century,[ref id="34"] creator of “Huapango”, a work that has earned the title of Mexico’s second national anthem.

Besides being a composer, percussionist, music teacher and conductor, Moncayo was a lover of Mexican landscape. As an amateur mountaineer he climbed the Popocatépetl, the Iztaccíhuatl and the Pico de Orizaba, collecting images and atmospheres that he managed to capture in his compositions.

It was Carlos Chávez who asked him to carry out musical research in Veracruz. Thanks to this assignment, the composer studied songs such as “Ziqui ziri”, “Balajú” and “El Gavilancito”, which influenced the creation of “Huapango”, premiered on August 15, 1941 at the Palace of Fine Arts, with the Mexican Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Carlos Chávez. Within his musical legacy, masterpieces such as “Muros verdes”, “Tierra”, “Hueyapan” and “Amatzinac” are also remembered.