A seasoning, marinade and color source. Annatto is an essential condiment in southeastern Mexico’s kitchens, thanks to which we have two national gastronomical glories: cochinita pibil and tacos al pastor, among many other dishes.

In pre-Hispanic Mexico it was considered a sacred plant and was used mainly as a pigment. The process to obtain annatto paste by decan-ting the powder found in seeds is a highly refined mayan technique.

After the discovery of America it was taken to Europe where it was used to dye everything from leather, wool, silk and cotton, to cheese, butter and smoked fish. It grows in southern Mexico, especially in Yucatán and Campeche; although currently it is also grown in countries such as Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.

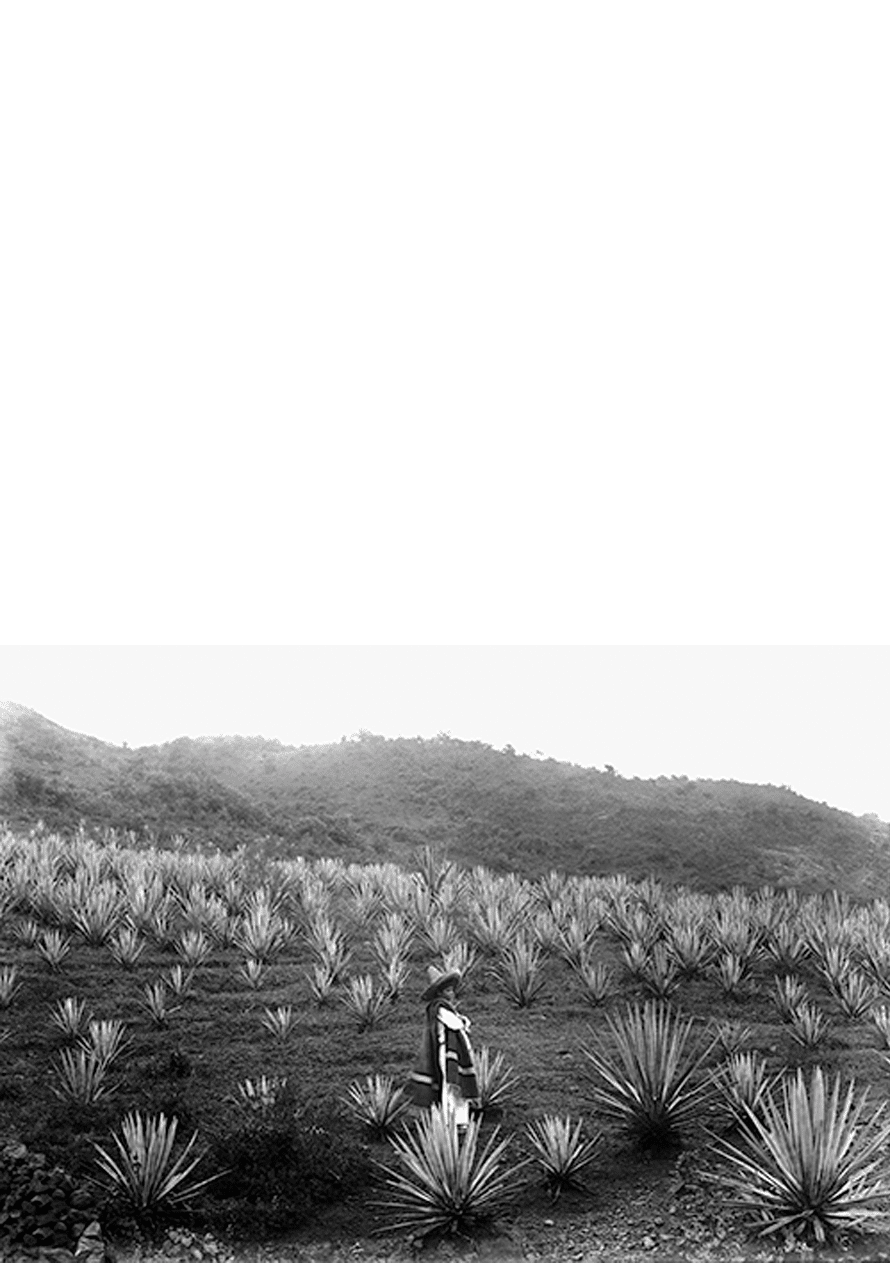

“There is a plant in this country that is both a tree and a thistle. Its leaves are thick as a knee and longer than an arm [...]. When mature, the indigenous people cut the base of the shoot, which produces a liqueur that they mix with the bark of a particular tree [...]. This tree is of the greatest use because it produces spirits, vinegar, honey and a concoction similar to the juice of a cooked grape”,1 this is how the Spaniards described maguey, a plant that attracted their attention when they arrived in the New World.

The indigenous people called it metl or mexcametl. When fermenting its mucilage they produced pulque, and took advantage of its fleshy leaves to extract a fiber with which they wove dresses, sandals and ropes, among other objects.

It was the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus who gave it the scientific name of Agave —which in Greek means “admirable”—, to name all plants of its genus. Of the over 285 varieties of agave that have been described in the world, 200 are found within Mexican territory. In addition to its importance for the production of the most representative drinks in the country, its cultivation helps stop soil erosion, its stem is used to build huts, and its roots are employed to make brushes and brooms.

Amongst Mexico’s gastronomic contributions to the world, avocado is the crown jewel. Its name comes from the Nahuatl word ahuacatl that means “tree testicles”. One of the first references about its consumption dates from 1519 and appears in the book Suma de geografía by Martín Fernández de Enciso: “Inside it is like butter, and of marvelous flavor, and leaving such a good and delicate taste that it is quite wonderful”.2

Mexico is the main supplier in the international market of this fruit of which flavor, texture and properties are so highly regarded that it is considered as “green gold”.

Its nutrients are also used in cosmetic formulas for the preparation of lotions, soaps, creams and hair products.

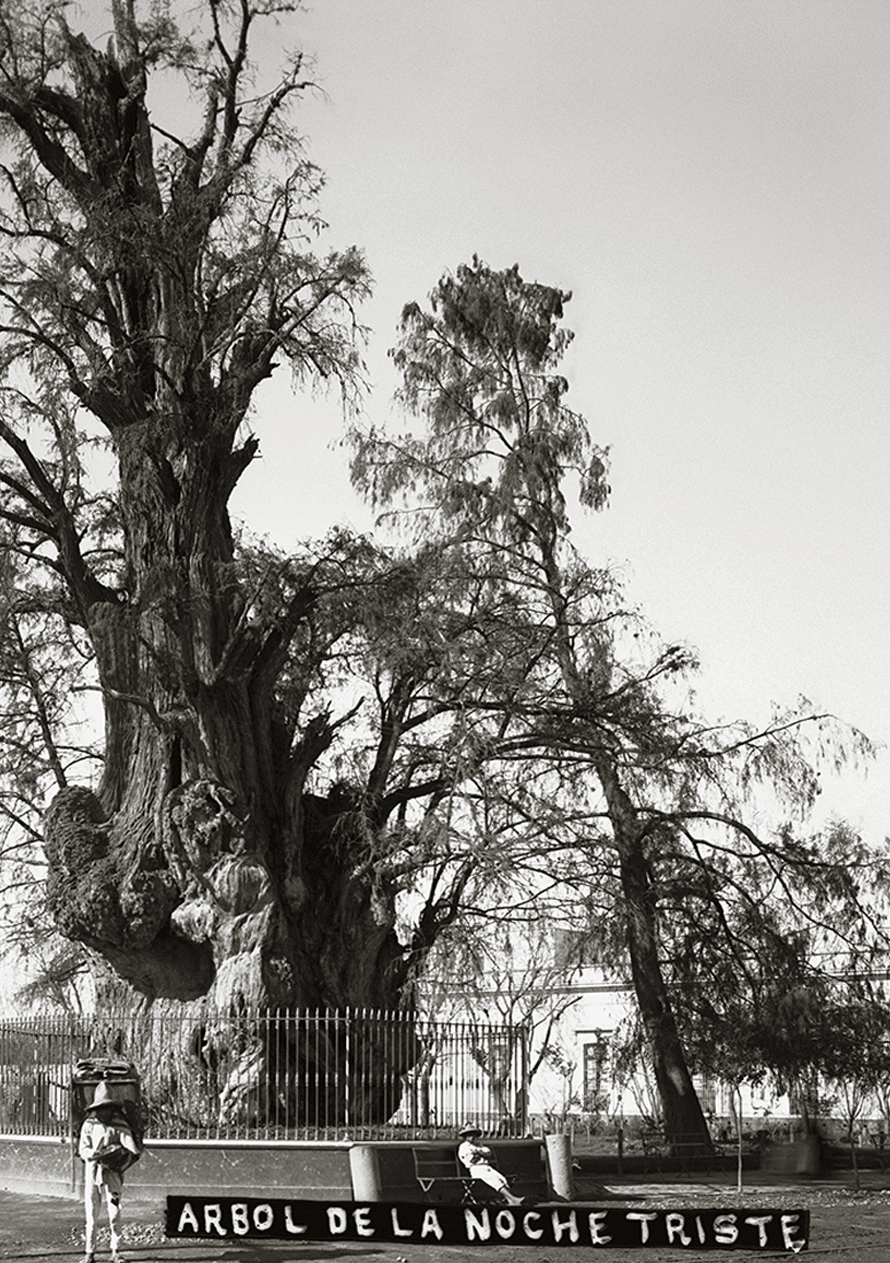

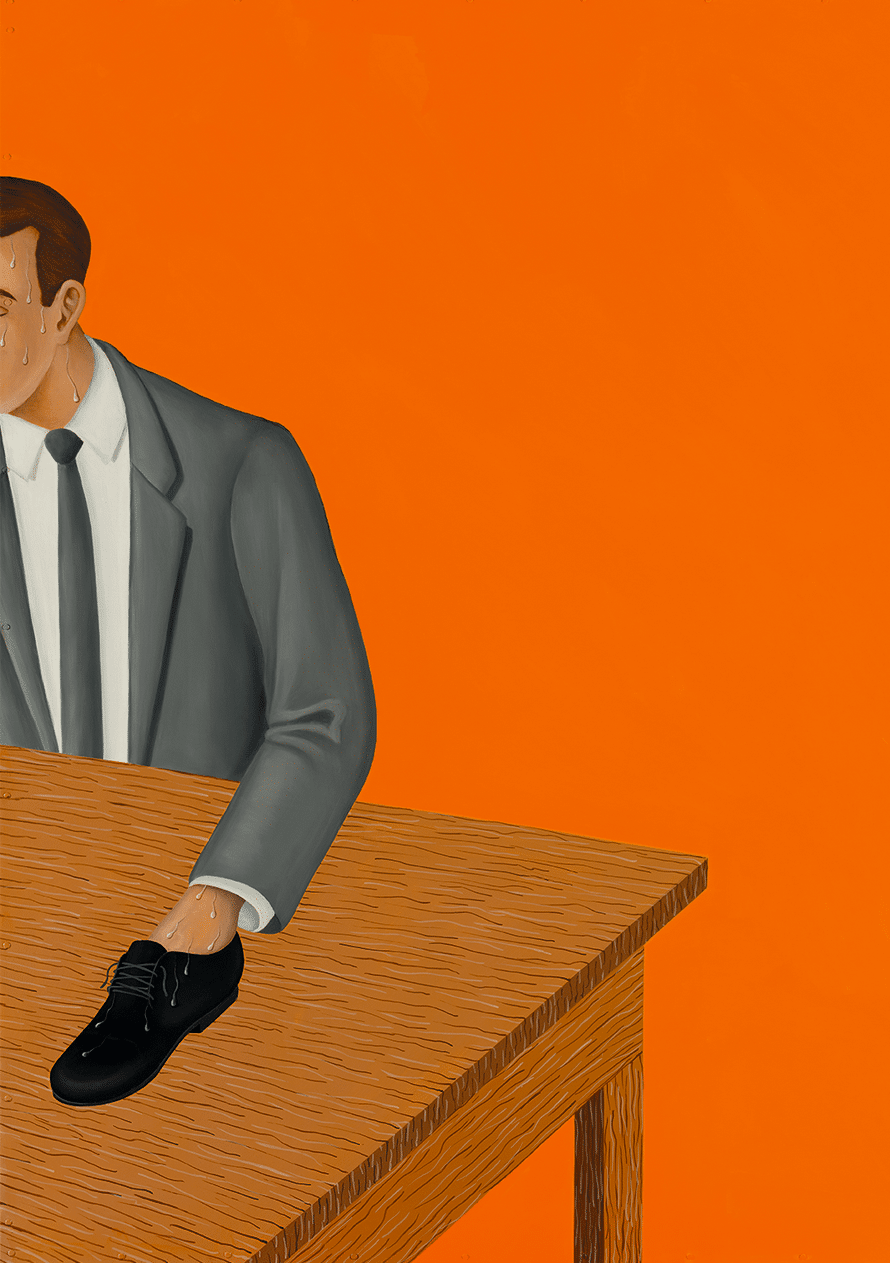

The ahuehuete is a millenary tree the name of which means “old man of the water”. Mexico is the only place where this species lives, which is considered the national tree.

Among famous ahuehuetes, the most controversial one is the Tree of the Sad Night —in Mexico City—, named that way for acting as the silent witness of Hernán Cortés’ tears after his defeat at the hands of the Aztecs. But, undoubtedly, the most famous ahuehuete in Mexico is the Tule Tree, located in Oaxaca. Its greatness and wisdom is celebrated every year in October, with the Tule Tree International Festival attended by hundreds of tourists from all over the world to sing “Las mañanitas” to its more than two thousand years.

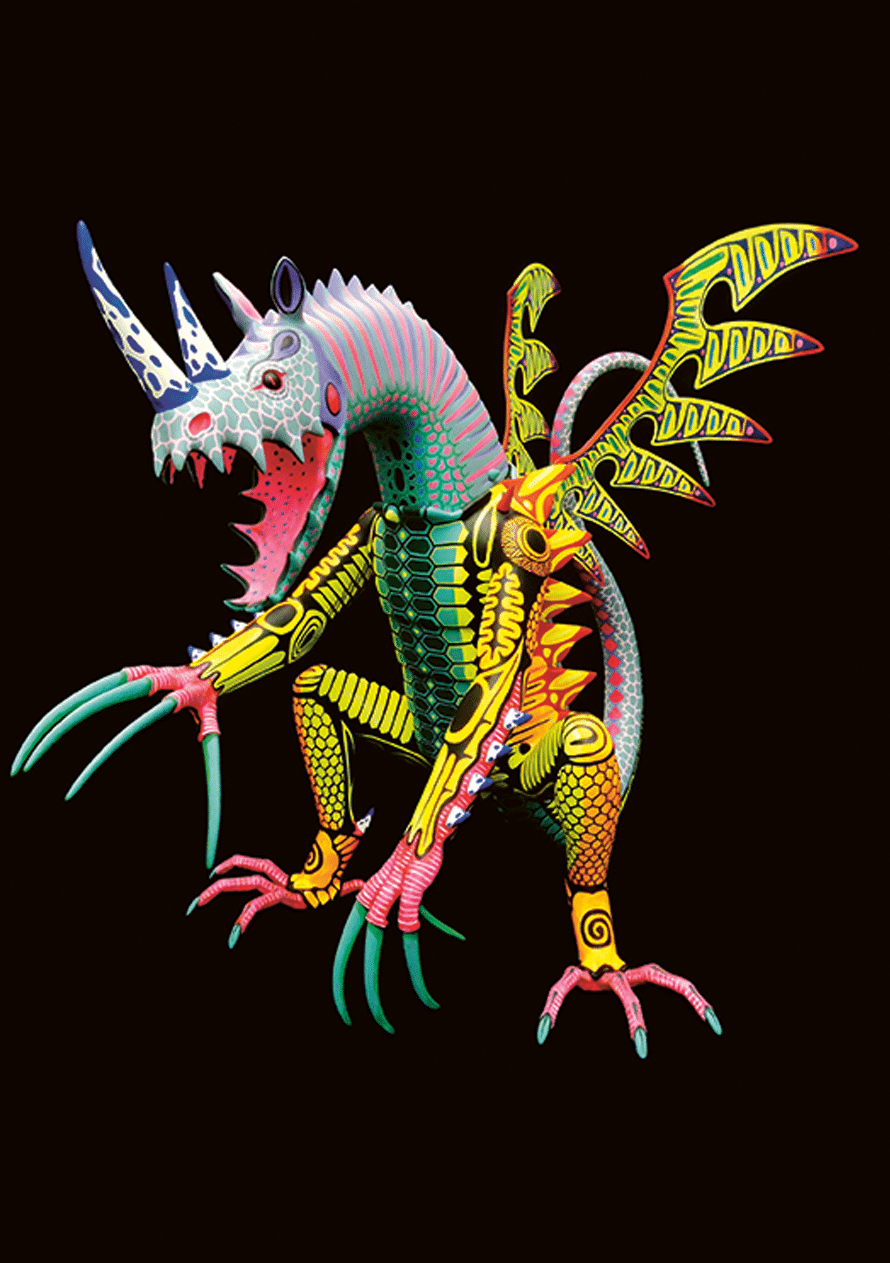

In the history of mankind, the recurring custom of creating figurines is found in different eras and cultures, and has been used for different purposes.

In Mesoamerica, Quetzalcóatl may well be the precedent of alebrijes, the colorful and mythical creatures that came to Mexico to protect the life and death of those who dream.

From 1927, Don Manuel Jiménez in Arrazola, in Oaxaca, and in the 1940s, Don Pedro Linares, in Mexico City, used these figures and forged a milestone in Mexican folk art history, making them from wood and cardboard, respectively.

Today, thanks to an impressive acceptance, alebrijes have become a reference of folk art.

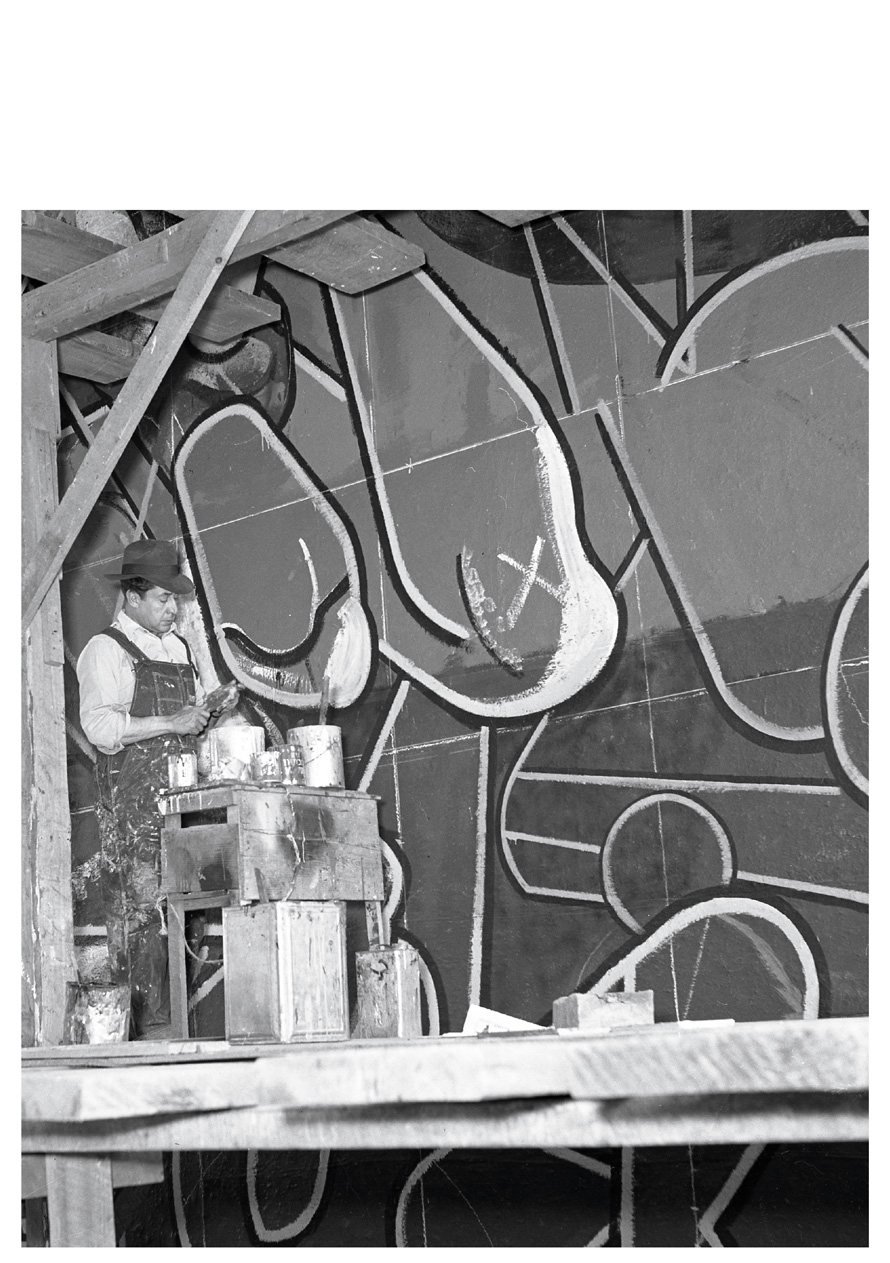

David Alfaro Siqueiros (Chihuahua, Chihuahua, 1899-Cuernavaca, Morelos, 1974) was the youngest, most controversial and radical of the three great Mexican muralists.

At age 16, as a student at the Academy of San Carlos, he changed his brushes for weapons and enlisted in the Constitutionalist Army to fight against the government of president Huerta. As a soldier, he walked along mountain ranges, deserts and hills while observing the life of peasants, workers and indigenous people, scenes that appeared constantly in his work.

In 1960, after finishing the mural From Porfirianism to the Revolution at the Chapultepec Castle, he was accused of social dissolution and incarcerated in the Lecumberri Prison. Six years later, he received the Lenin Peace Prize and the National Fine Arts Award of Mexico.

His work can be admired in public buildings such as the Palace of Fine Arts, the UNAM’s main campus or the Polyforum Siqueiros, among others, in Mexico City. In 2003, the international press reported one more controversy over the artist, when an erotic mural of his authorship, Plastic Exercise, painted in 1933 in the basement of a mansion in Buenos Aires, reached a price of over 20 million dollars.

This microscopic blue-green algae was known in pre-Hispanic times as tecuitlat, which means “stone excrement”. Mexicas harvested it in the surroundings of Lake Texcoco to make a paste that the Spaniards named “earth cheese”.

Nowadays, it is known as a superfood because it provides a much more digestible protein intake than red meat, in addition to a large amount of vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, chlorophyll and a wide range of phytochemicals. It is one of the most appreciated food supplements in the world, chosen by NASA to enrich the diet of astronauts in space missions.

Francis Alÿs was born in Antwerp, Belgium, in 1959. An architect by profession, he never sought to dedicate himself to art or live in Mexico, where he arrived in 1986 fleeing from military duty in his country. He worked for a French organization that supported the reconstruction of the capital after the 1985 earthquake.

Among the ruins of the city he found an observation lab from where his first artistic projects arose. Since those days he has continued to experiment with a mixture of disciplines such as painting, photography, audiovisuals and performance, which have taken him around the world, renown as one of the most influential artists of his generation.

One of his first memorable actions was Sometimes Making Something Leads to Nothing in 1997, which consisted of dragging a large ice cube along the streets of the Tepito neighborhood; as it passed, the block left a trace of moisture that soon disappeared, until it was reduced to a small stone.

Alÿs uses poetic and allegorical methods to address political and social realities, such as national borders, localism and globalism, as well as the benefits and detriments of progress.

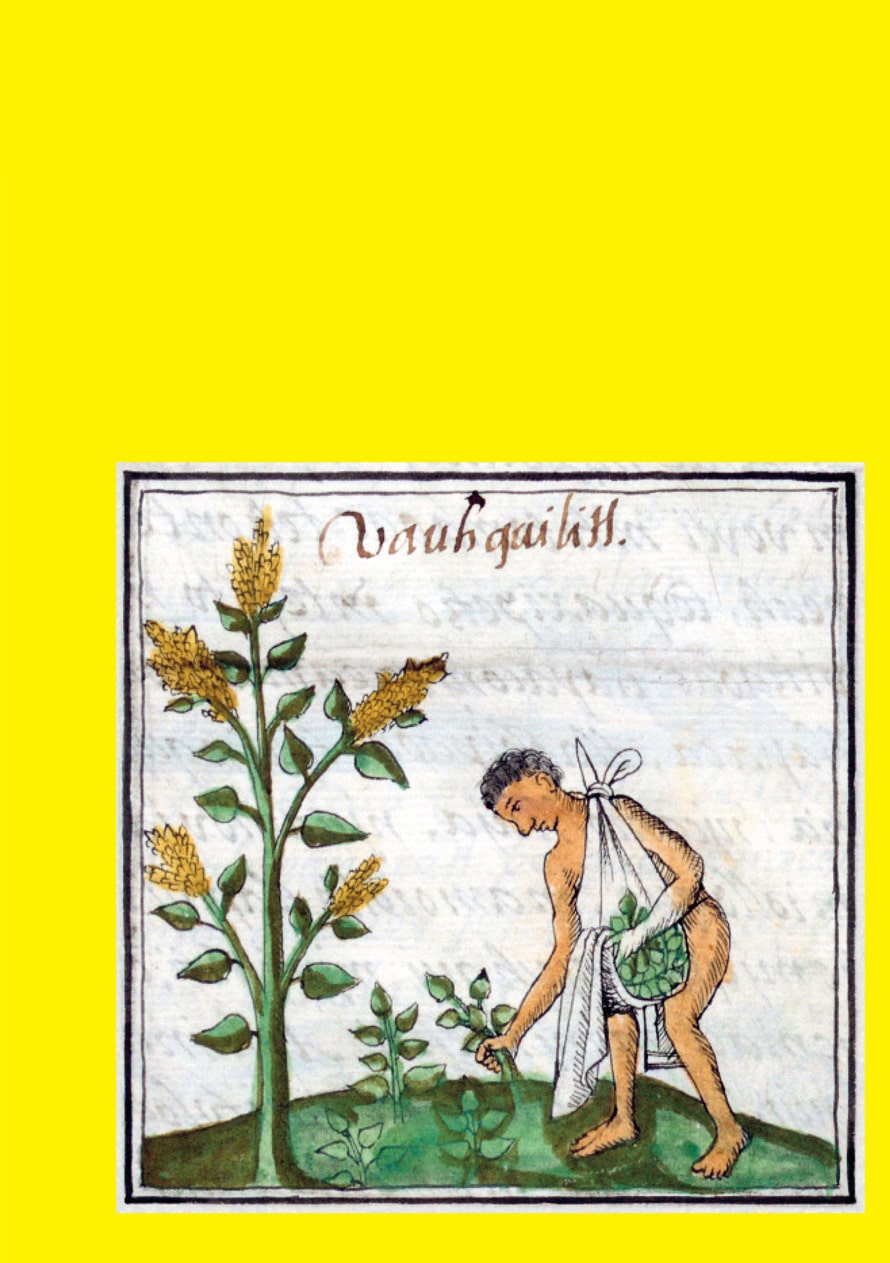

The four essential foods in the diet of ancient Mexicans were maize, beans, chili and amaranth. Aztecs considered amaranth as the food of gods. The ritual use of its seed gave body to the deities and its dust, like pinolli, was a fundamental provision that gave vitality to the mortal body of travelers.

Due to the strong link between amaranth and indigenous religious rituals, Christian missionaries almost eradicated its cultivation; fortunately, amaranth grew wild and its use continued. “Alegrías” —sweets made from amaranth and maguey honey— survived and have continued to nourish Mexican people to this day. At the end of the 20th century, the enormous nutritional value of amaranth was rediscovered, and it has even been suggested as a possible resource against world hunger.

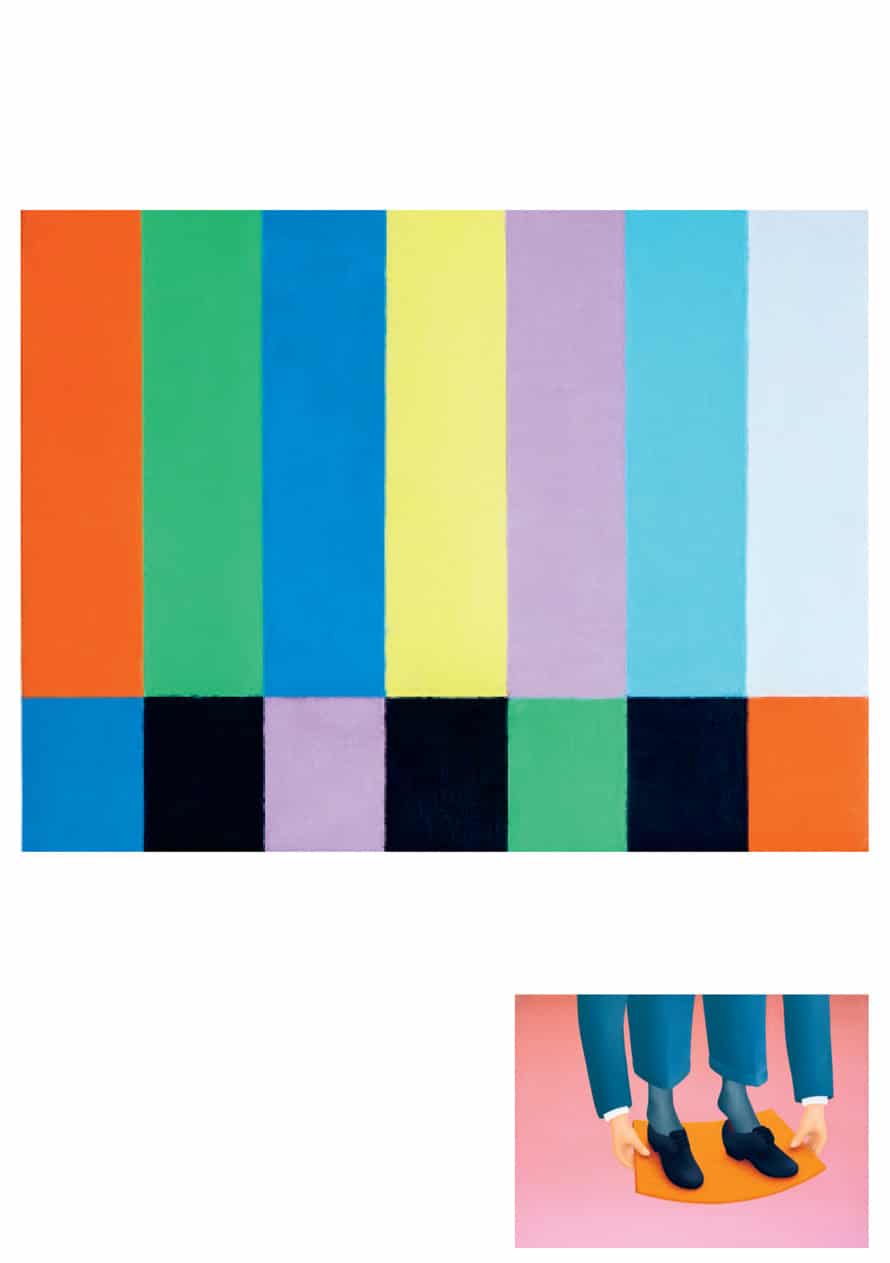

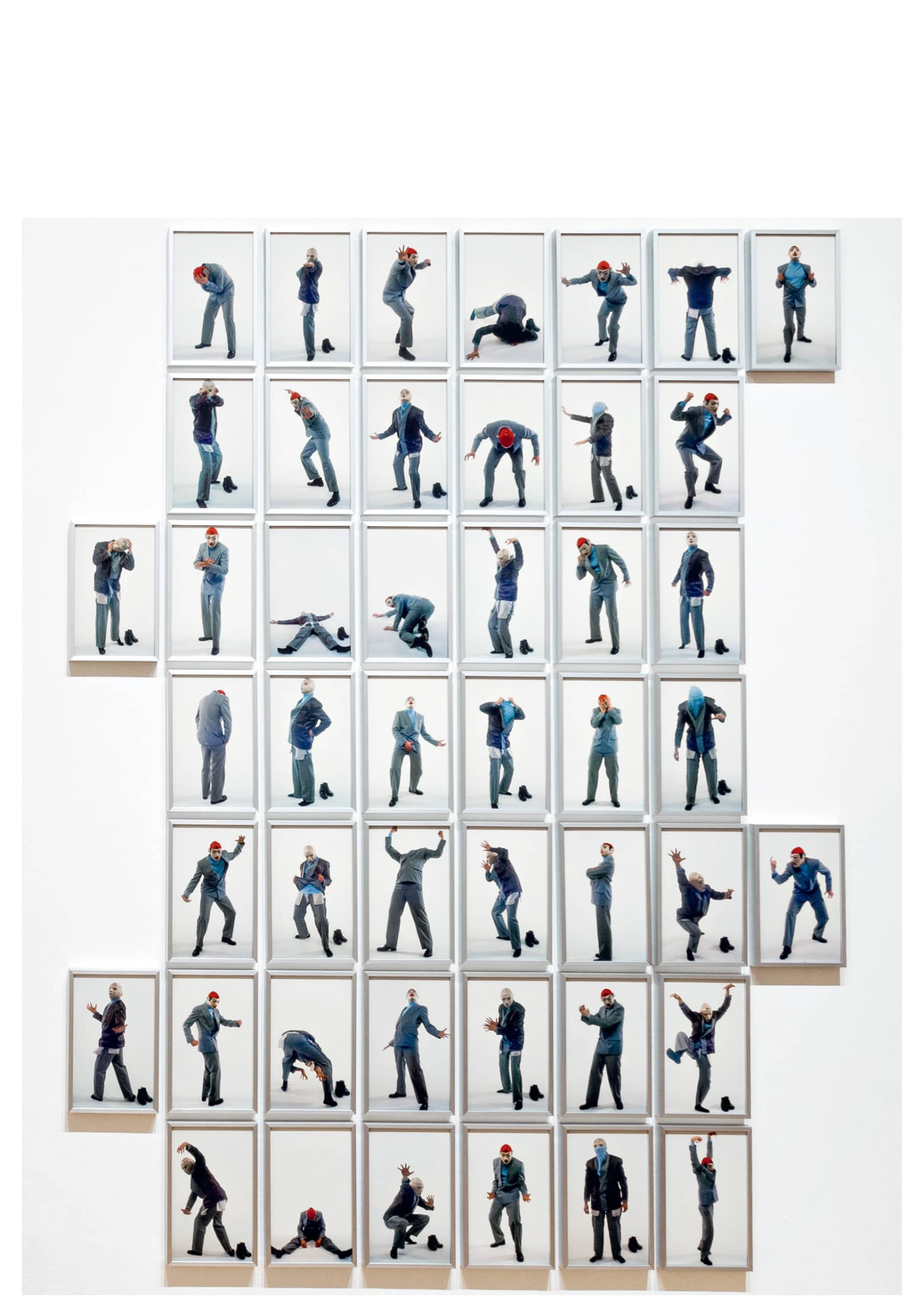

With over twenty years of experience, Carlos Amorales (Mexico City, 1970) has dedicated his life to exploring and transgressing the limits of language through a combination of media sources, including graphics, sculpture, film, performance and music.

Examples of his obsession with deconstruction and playfulness begin with his name, which went from being Carlos Aguirre Morales to the word game “Carlos a moral es” taking the “A” from Aguirre and separating “Morales”, which translates into “Carlos is amoral”.

His high points include works such as Life in the Folds, representing the Mexico Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The installation exhibited a series of ocarinas that as a whole created an encrypted alphabet. The artist also created a set of scores that were later performed in the short film The Cursed Village, which tells the story of a family of migrants who are lynched when they arrive in a village.

About the exhibition he explained: “Life in the Folds is based on the title of a novel by Henri Michaux evoking an image about being between things: between the pages of a book or a newspaper, between countries and cultures, between opposed ideologies, between oneself and the other. This ‘being between’ has been the focus of my artistic exploration: masks, whether taken literally or as visual language, placed like a membrane between conflicting contexts”.3

Amorales has exhibited his work in important galleries around the world. Among his most important showings are Axioms for Action (MUAC, Mexico City, 2018) and Herramientas de trabajo (MAMM, Medellín, Colombia, 2017).

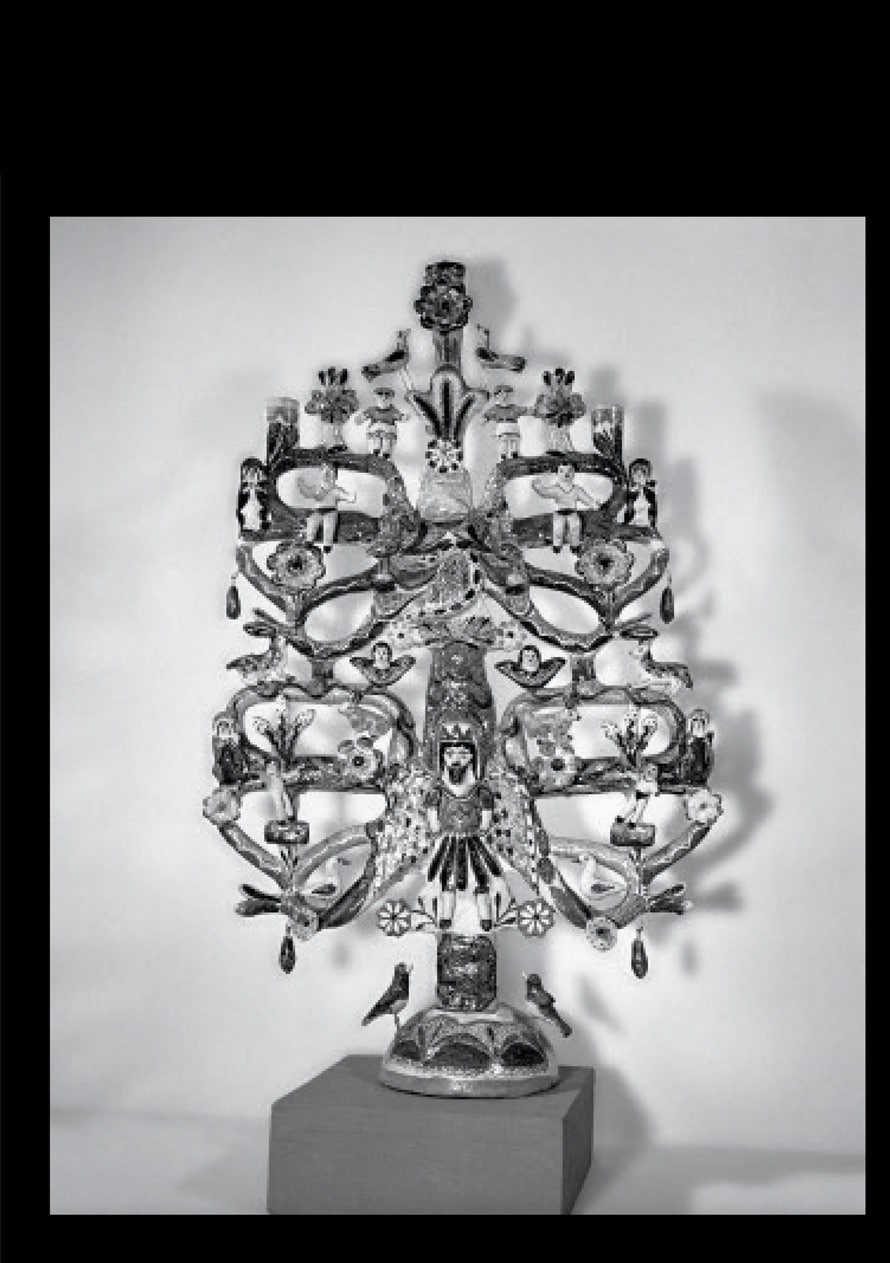

The tree of life is one of the most renowned Mexican handicrafts worldwide. Its origin dates back to pre-Hispanic times, when the Teotihuacan, Otomi, Matlatzinca and Mexica peoples used clay to make ceramics for ceremonial uses and utensils for everyday life.

During the spiritual conquest, in the colonial era, clay deities were replaced by a tree of life —a representation of the biblical creationist theory— as an instrument of evangelization. Over time, indigenous artisans appropriated the allegory transforming it from a religious object to a folkloric representation accounting for the worldview of each craftsman.

Trees of life are produced in Izúcar de Matamoros, Puebla; in Acatlán, Puebla; and especially in Metepec, State of Mexico. They have been exhibited in museums in Europe, Asia and North America as valuable artistic objects.

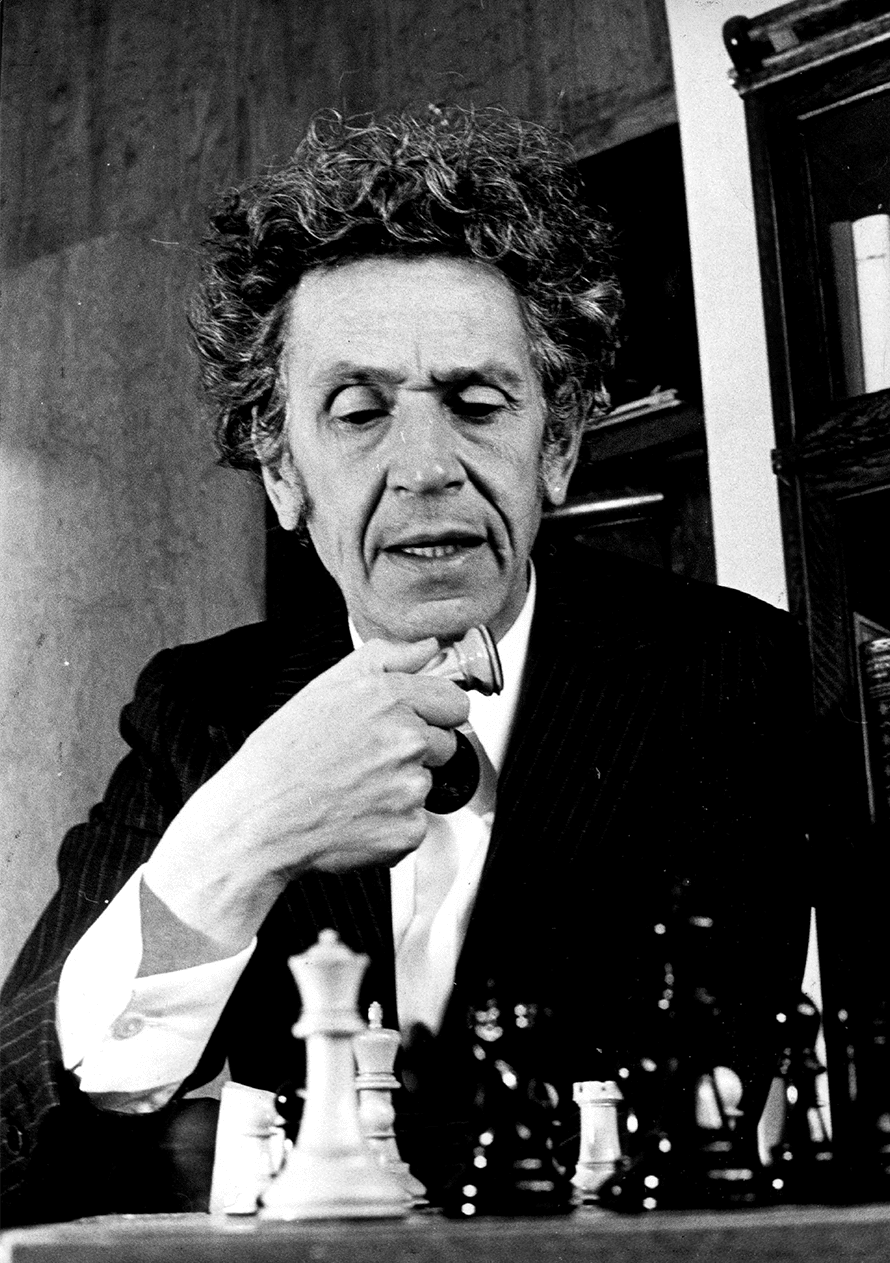

Legend has it that Juan José Arreola (1918-2001) was born with the gift of gab. In his village, Zapotlán El Grande, Jalisco, he was famous for being a reciter who from an early age assumed his passion for language.

Because of the Cristero War, which closed schools run by churches, he had to abandon formal studies and self-taught himself. When he turned 17, he left Zapotlán to go to Mexico City where he studied theatre.

His book Varia invención, published in 1949, placed him in the scene of Mexican literature. This stylistic exercise combining prose and poetry in different voices caught the attention of writer Jorge Luis Borges, who asked to meet the author in one of his visits to Mexico.

According to the Colombian critic Fabio Jurado: “Borges was the first to acknowledge Juan José Arreola as the author who was already revolutionizing and innovating Latin American narrative. That link with Borges makes us perceive in Arreola a presence of universal literature”.4

To speak of Juan José Arreola is to encompass a universe that combined histrionism with the written word, play, wit, laughter, memory and tradition. He is an essential writer in the history of our country’s literature and a reference that left a mark in the world of cultural television, entertainment and dissemination of culture.

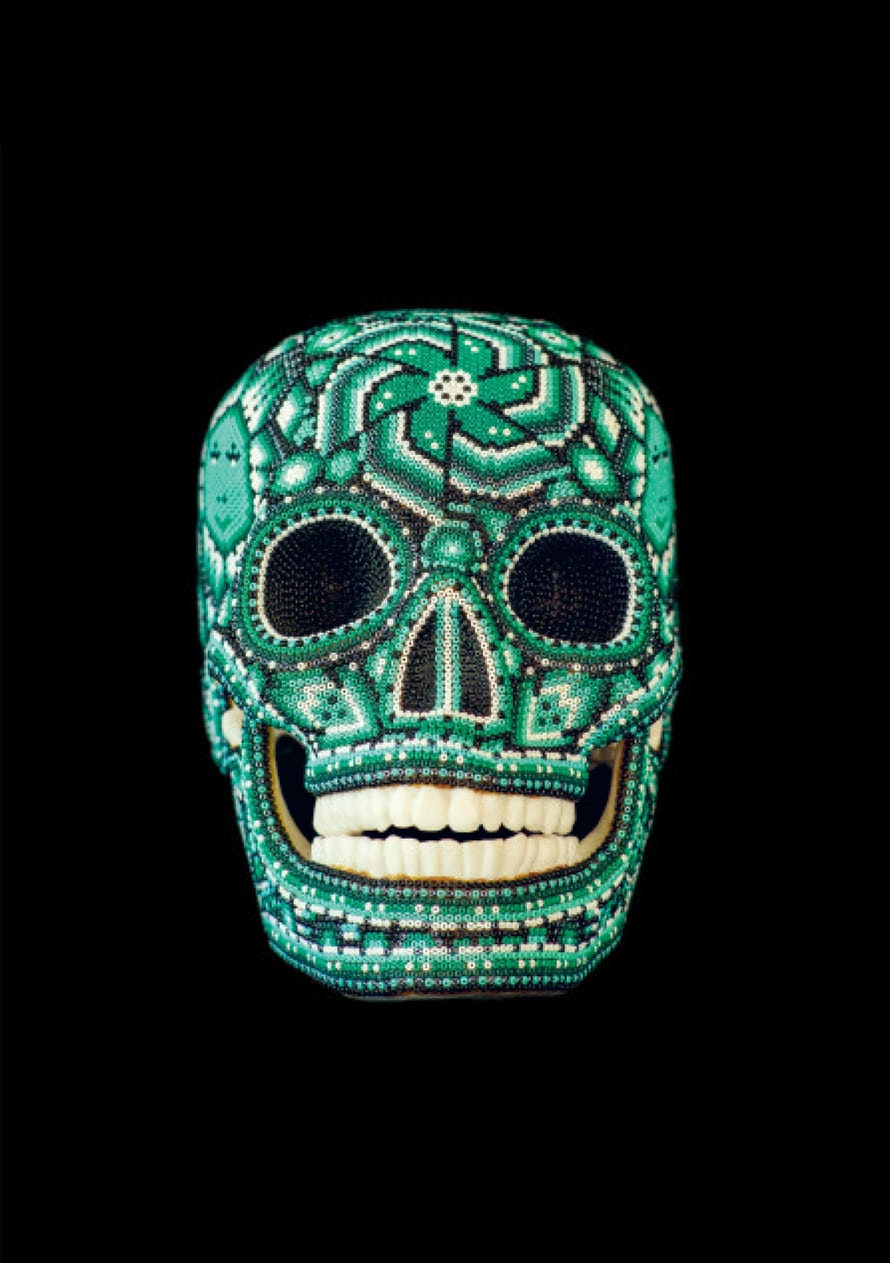

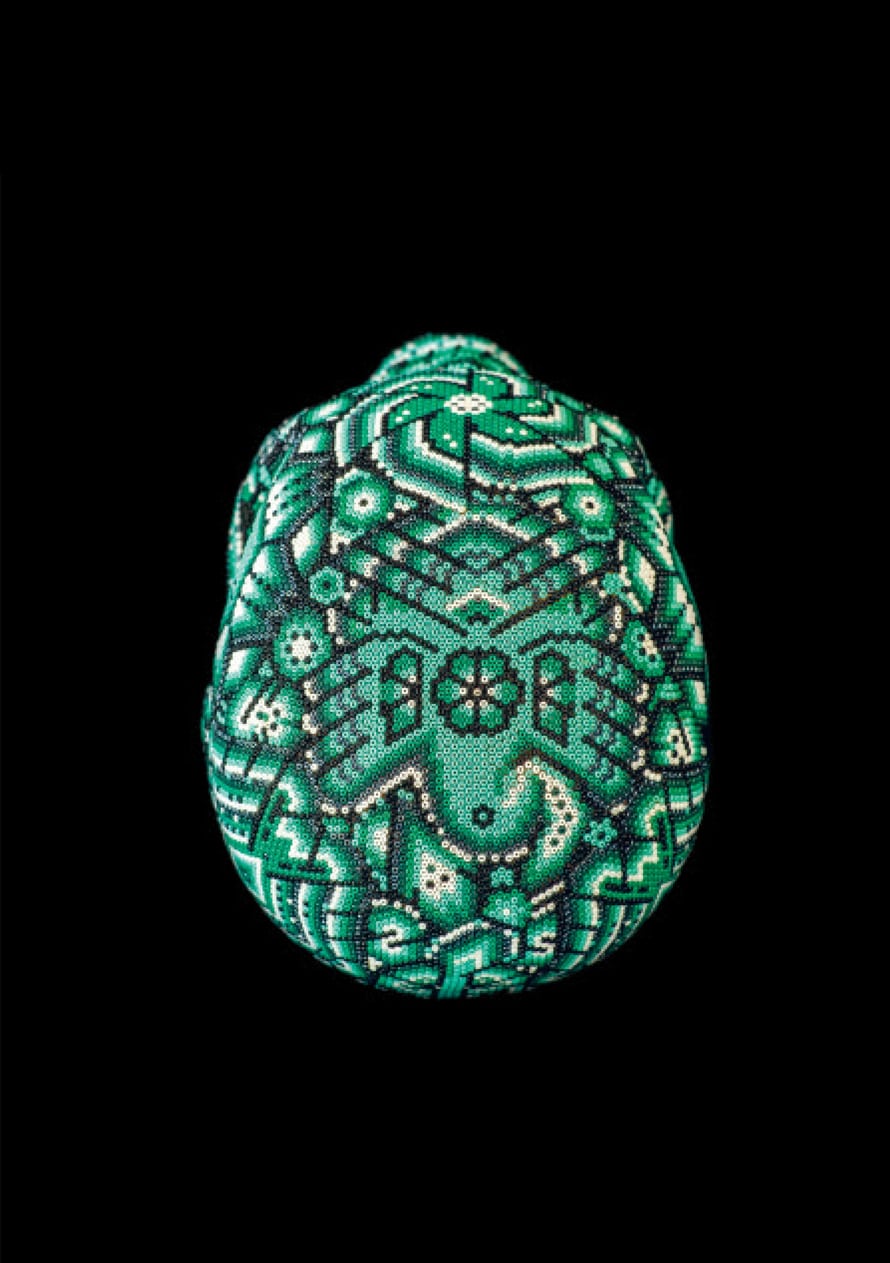

Appreciated throughout the world, Huichol art was born as an offering to the gods. It is created by the hands of an ethnic group that lives in the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range of Mexico, which includes the states of Jalisco, Nayarit, Durango and Zacatecas.

Like a sacred script that protects history and tradition, Wirraritari artists use colors, symbols and geometric figures, combined with everyday forms to make their creations on beaded sculptures, yarn pictures and jewelry, which become representations of their worldview. More than work, for these artists each of their pieces means the opportunity to communicate with the creator.

For the Huichol, nierika is the gift of seeing, a mirror where their shaman, the marakame, can observe images stemmed from a magical world, which can be entered with peyote cactus; it is an ancestral tech- nique through which artists find different ways to materialize the messages of divinity.

Although now they use plastic beads and yarn —stuck with beeswax and pine resin—, these works were originally made with seeds, shells, small stones and feather filaments. The production of each piece takes an average of 50 hours, during which the artists pray to restore harmony that should exist between all beings that inhabit earth.

Atole is a beverage inherited from pre-Hispanic cultures made from maize dough and water, of different thicknesses and flavors.

The Nahuas were known for their light diet and were not accustomed to having breakfast. At midmorning, after a few hours of work, they drank a bowl of atolli —which means watery in Nahuatl— as their first nourishment; they drank it natural, sweetened with honey or seasoned with chili.

Atole is still an everyday drink for Mexicans and among its flavors and types are: strawberry, guava, pineapple, plum, capulin cherry, coconut, walnut, almond, St John’s wort, pinole, ash, white chocolate, with pieces of brown sugar, sour or xocoatole, cuatole (with honey and chili), chileatole, mezquiatole, xole (with cacao), nacuatole (with honey and pumpkin), broad bean and watónali (with fruits or herbs).

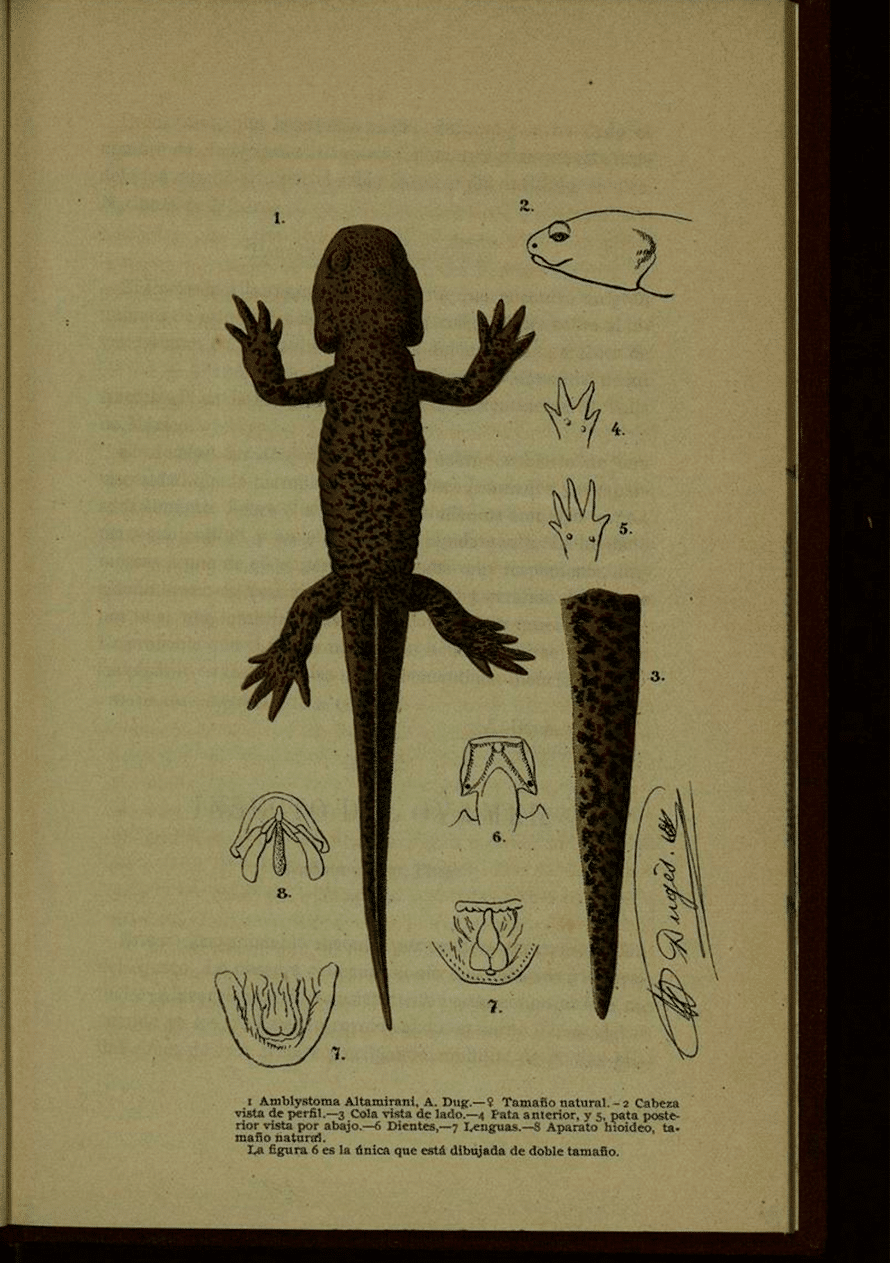

This amphibian from the salamander family lives exclusively in certain bodies of water in the Valley of Mexico, specifically in Lake Xochimilco. It is therefore considered a symbol of cultural identity of the capital of the Republic.

The axolotl or water monster is the only animal in the world capable of reproducing itself in larval state, in which it remains at will. It has an extraordinary ability to regenerate amputated limbs, tissues and organs of its body, including the brain. For this reason ancient settlers of the Valley of Mexico saw it as a being that defied death and considered it in their mythology as the aquatic incarnation of the Aztec god Xolotl, twin brother of Quetzalcóatl.

Its biological qualities have fascinated researchers and scientists around the world. Recently it was discovered that its genome is the largest sequenced to date, ten times greater than human’s. Unfortunately, the mysteries protected in its genetics might never be revealed, since it is in danger of extinction due to lake pollution and the introduction of exotic species into its natural habitat.