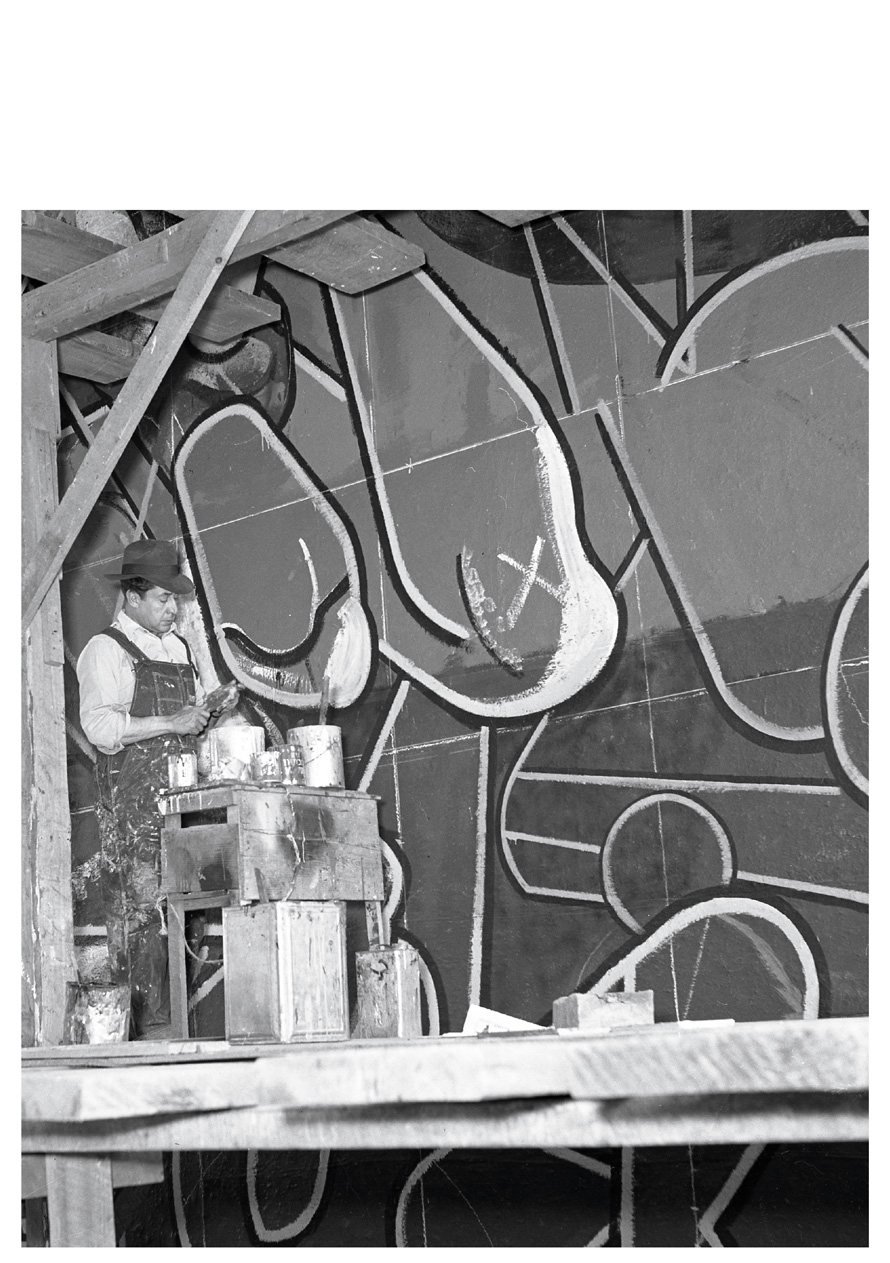

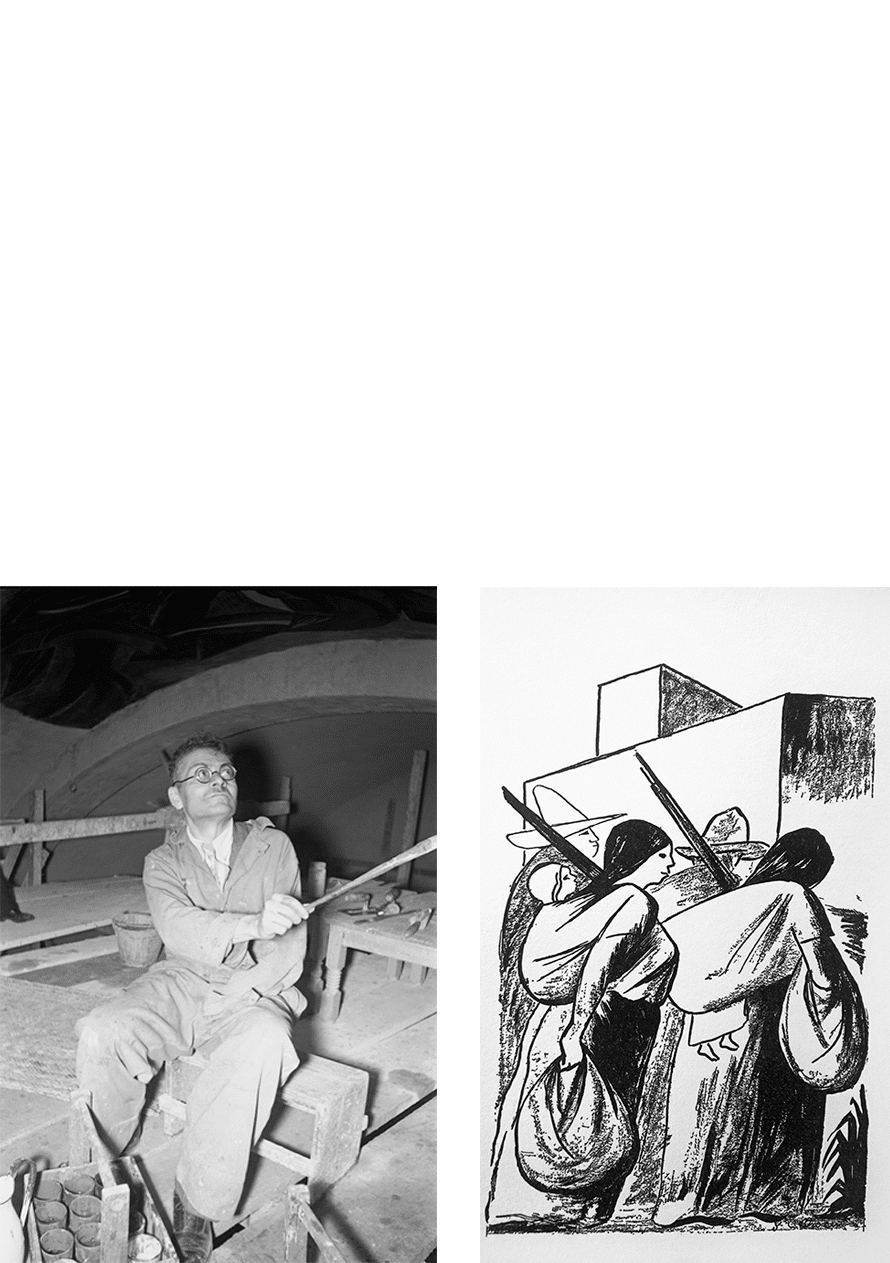

David Alfaro Siqueiros (Chihuahua, Chihuahua, 1899-Cuernavaca, Morelos, 1974) was the youngest, most controversial and radical of the three great Mexican muralists.

At age 16, as a student at the Academy of San Carlos, he changed his brushes for weapons and enlisted in the Constitutionalist Army to fight against the government of president Huerta. As a soldier, he walked along mountain ranges, deserts and hills while observing the life of peasants, workers and indigenous people, scenes that appeared constantly in his work.

In 1960, after finishing the mural From Porfirianism to the Revolution at the Chapultepec Castle, he was accused of social dissolution and incarcerated in the Lecumberri Prison. Six years later, he received the Lenin Peace Prize and the National Fine Arts Award of Mexico.

His work can be admired in public buildings such as the Palace of Fine Arts, the UNAM’s main campus or the Polyforum Siqueiros, among others, in Mexico City. In 2003, the international press reported one more controversy over the artist, when an erotic mural of his authorship, Plastic Exercise, painted in 1933 in the basement of a mansion in Buenos Aires, reached a price of over 20 million dollars.

Francis Alÿs was born in Antwerp, Belgium, in 1959. An architect by profession, he never sought to dedicate himself to art or live in Mexico, where he arrived in 1986 fleeing from military duty in his country. He worked for a French organization that supported the reconstruction of the capital after the 1985 earthquake.

Among the ruins of the city he found an observation lab from where his first artistic projects arose. Since those days he has continued to experiment with a mixture of disciplines such as painting, photography, audiovisuals and performance, which have taken him around the world, renown as one of the most influential artists of his generation.

One of his first memorable actions was Sometimes Making Something Leads to Nothing in 1997, which consisted of dragging a large ice cube along the streets of the Tepito neighborhood; as it passed, the block left a trace of moisture that soon disappeared, until it was reduced to a small stone.

Alÿs uses poetic and allegorical methods to address political and social realities, such as national borders, localism and globalism, as well as the benefits and detriments of progress.

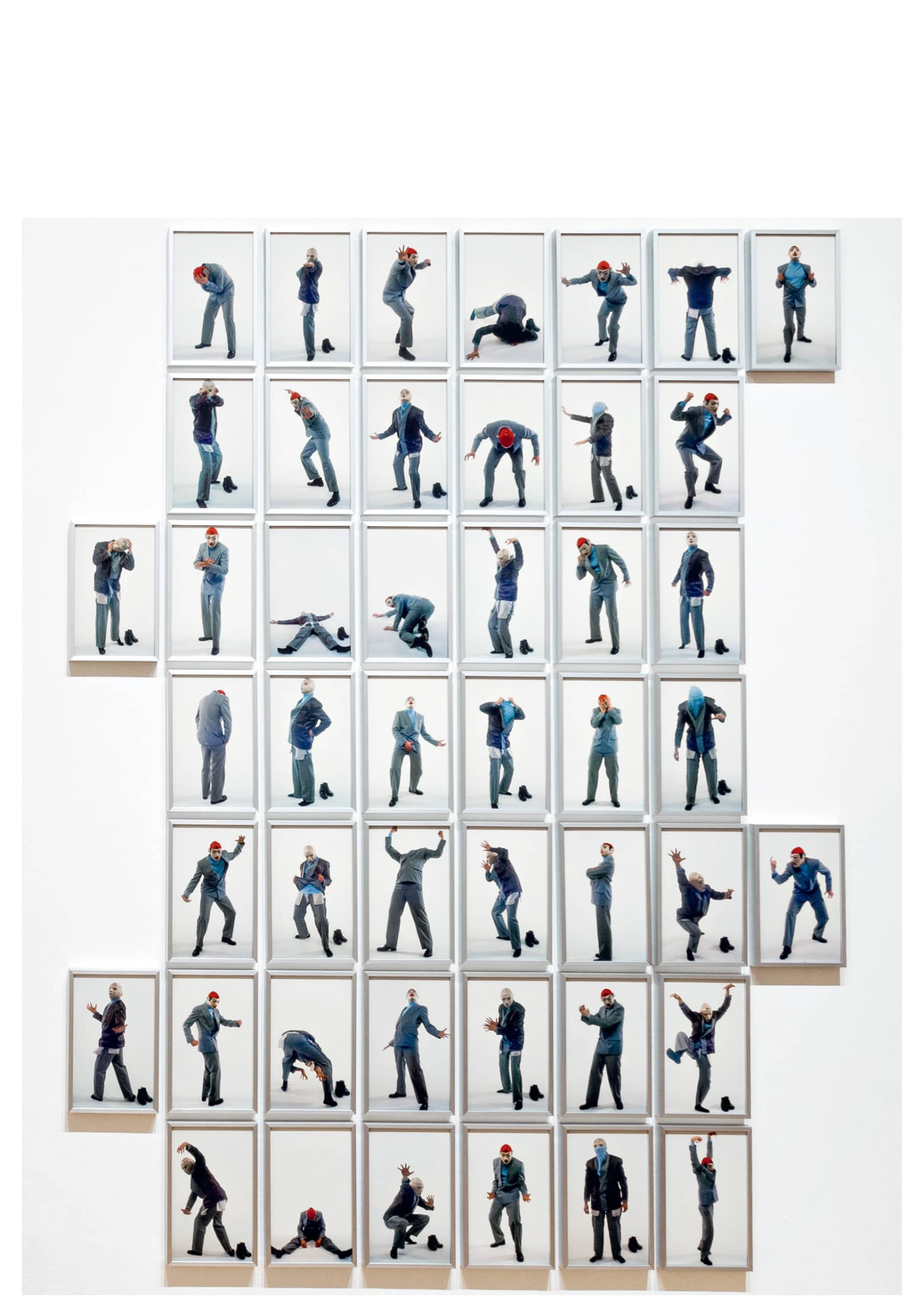

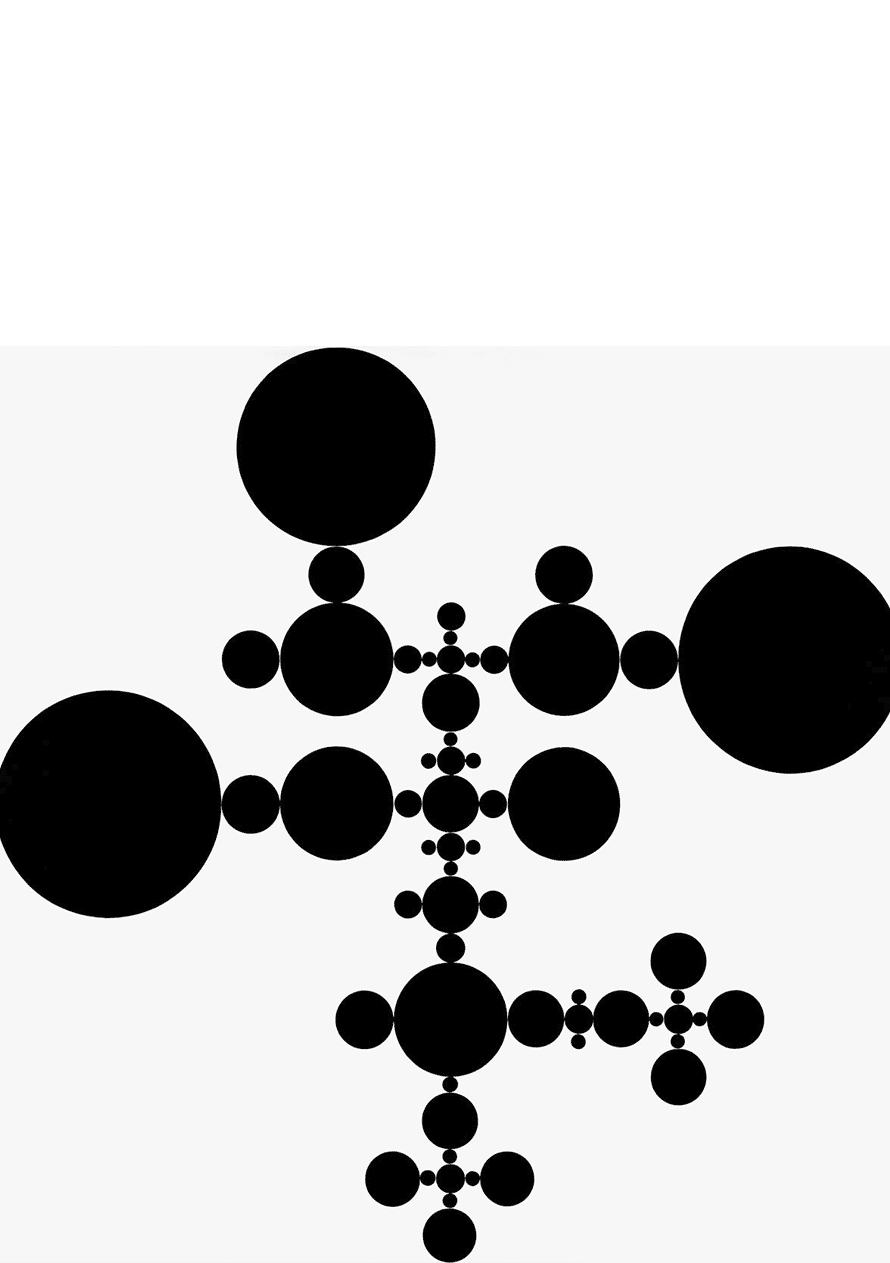

With over twenty years of experience, Carlos Amorales (Mexico City, 1970) has dedicated his life to exploring and transgressing the limits of language through a combination of media sources, including graphics, sculpture, film, performance and music.

Examples of his obsession with deconstruction and playfulness begin with his name, which went from being Carlos Aguirre Morales to the word game “Carlos a moral es” taking the “A” from Aguirre and separating “Morales”, which translates into “Carlos is amoral”.

His high points include works such as Life in the Folds, representing the Mexico Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The installation exhibited a series of ocarinas that as a whole created an encrypted alphabet. The artist also created a set of scores that were later performed in the short film The Cursed Village, which tells the story of a family of migrants who are lynched when they arrive in a village.

About the exhibition he explained: “Life in the Folds is based on the title of a novel by Henri Michaux evoking an image about being between things: between the pages of a book or a newspaper, between countries and cultures, between opposed ideologies, between oneself and the other. This ‘being between’ has been the focus of my artistic exploration: masks, whether taken literally or as visual language, placed like a membrane between conflicting contexts”.3

Amorales has exhibited his work in important galleries around the world. Among his most important showings are Axioms for Action (MUAC, Mexico City, 2018) and Herramientas de trabajo (MAMM, Medellín, Colombia, 2017).

José Hermenegildo de la Luz Bustos Hernández (1832-1907) was born in Purísima del Rincón, a small village in the state of Guanajuato, which he bearly left. He began to paint at a very early age and, unlike many artists of his time, he had no artistic training, so his self-taught search distanced him from the canon established at a time when painting was academic and copied European models.

He lived humbly and, although his origin was mixed race, he was always proud of his indigenous roots. He used to say, “I am indigenous and proud of it”. In addition to selling his drawings and portraits, he earned his living working as a healer, tinsmith, carpenter, master builder, bricklayer and ice cream seller.

The body of his work consists of more than four hundred paintings, mostly portraits, religious scenes and still life that are characterized by the precision and richness of their details. His legacy tended towards popular arts and was a great influence for artists like José Guadalupe Posada and many others who came later.

Textile art, sculptures, installations and performance are some forms that artist Pía Camil (Mexico City, 1980) has experimented with throughout her career. Her work reflects a story through warp and weft, and reflects on the psychology of consumption, also questioning the relationship between art and mass culture.

In 2015, she was brought into focus at the Frieze New York art fair, with the exhibition entitled Slats, Skins & Shop Fittings, which featured pieces that were somewhere in between the functional and the aesthetic. As a result, eight hundred ponchos made from second-hand fabrics and waste rescued from La Merced factories were given away to the visitors.

Her work has been exhibited in important galleries in Mexico, Colombia, France and the United States. She has also been distinguished with awards such as the European Honors Program at the Palazzo Cenci in Rome, Italy in 2001.

Leonora Carrington (Lancashire, England, 1917- Mexico City, 2011) was one of the most prominent artists of the Surrealist movement. Painter, sculptor and writer, her work is known for merging autobiographical and oneiric elements.

She arrived in Mexico in 1942, leaving behind boarding schools run by nuns, psychiatric hospitals and failed marriages. Here she found a second homeland and a new life: she got her Mexican citizenship; joined the feminist movement; formed a family together with Hungarian photographer Emir “Chiki” Weisz; became a part of the group “Poesía en voz alta” alongside Octavio Paz and Juan José Arreola; made brief appearances in several films; and devoted herself to understanding the worldview of indigenous cultures, the rituals around the dead and the shamanic metamorphoses that influenced her work.

The house in the Roma neighborhood where she lived for 61 years has been turned into the first museum dedicated to her work.

Ulises did not want to be a hostage of his passport. He wanted to be and he became a universal artist. All artists are countries in themselves. His passport is just a fingerprint.13

João Fernandes, Deputy Director of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

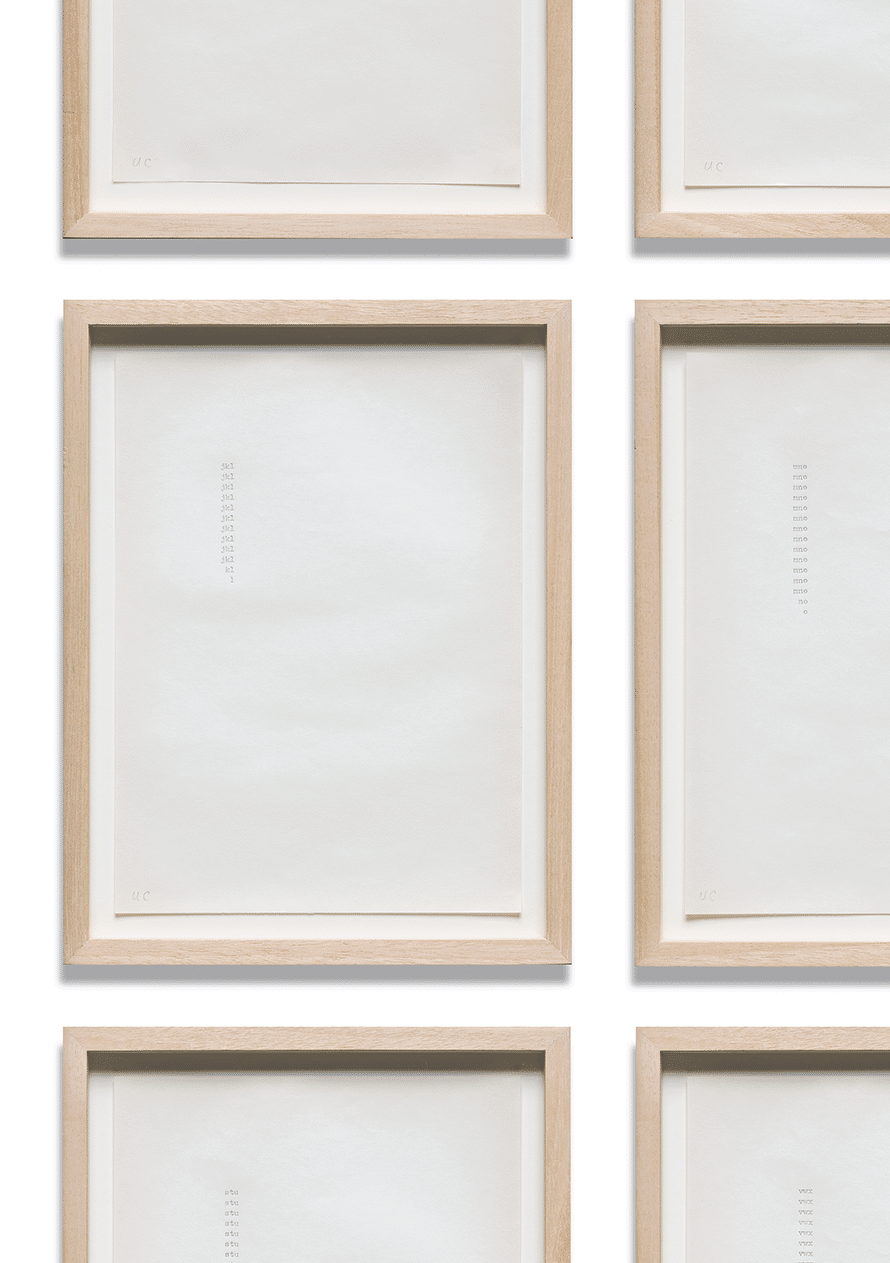

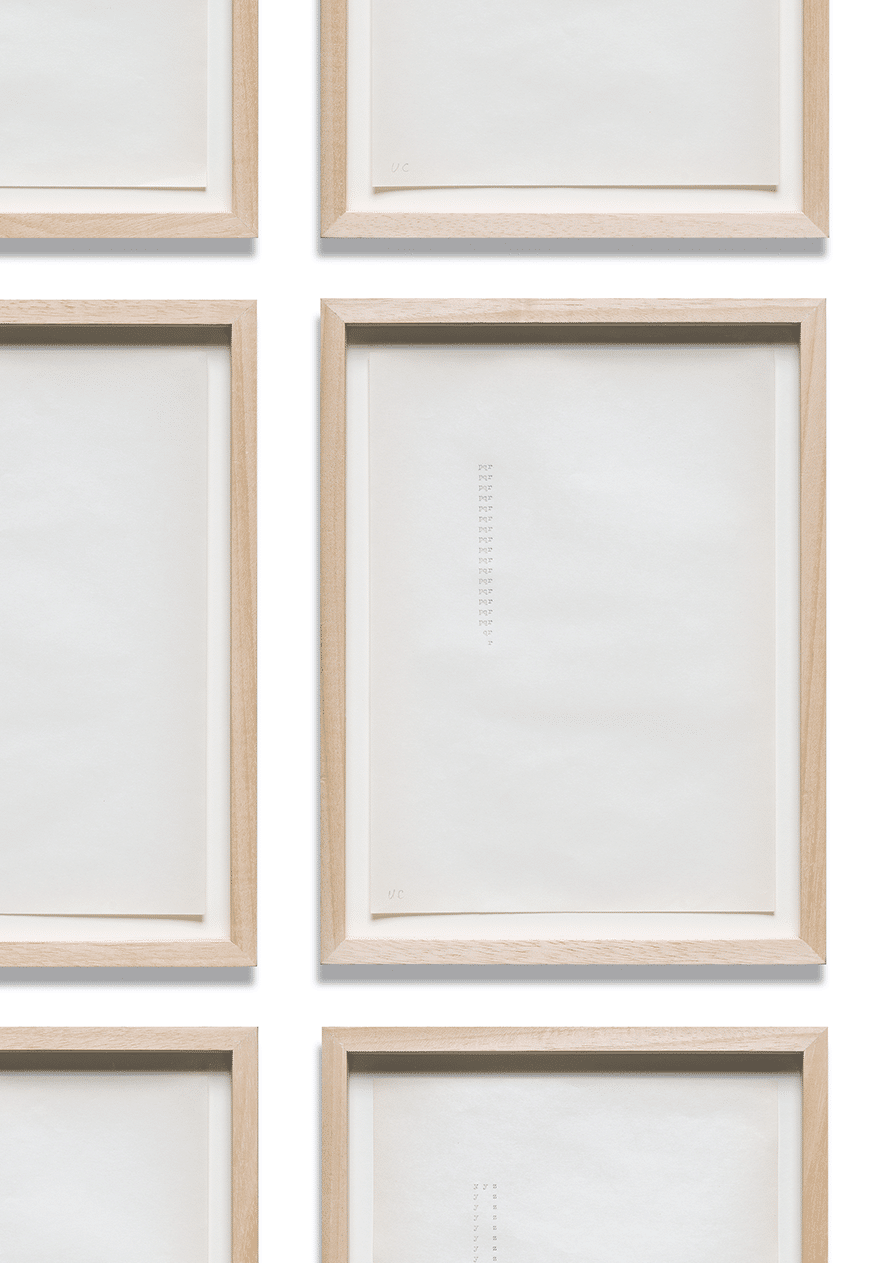

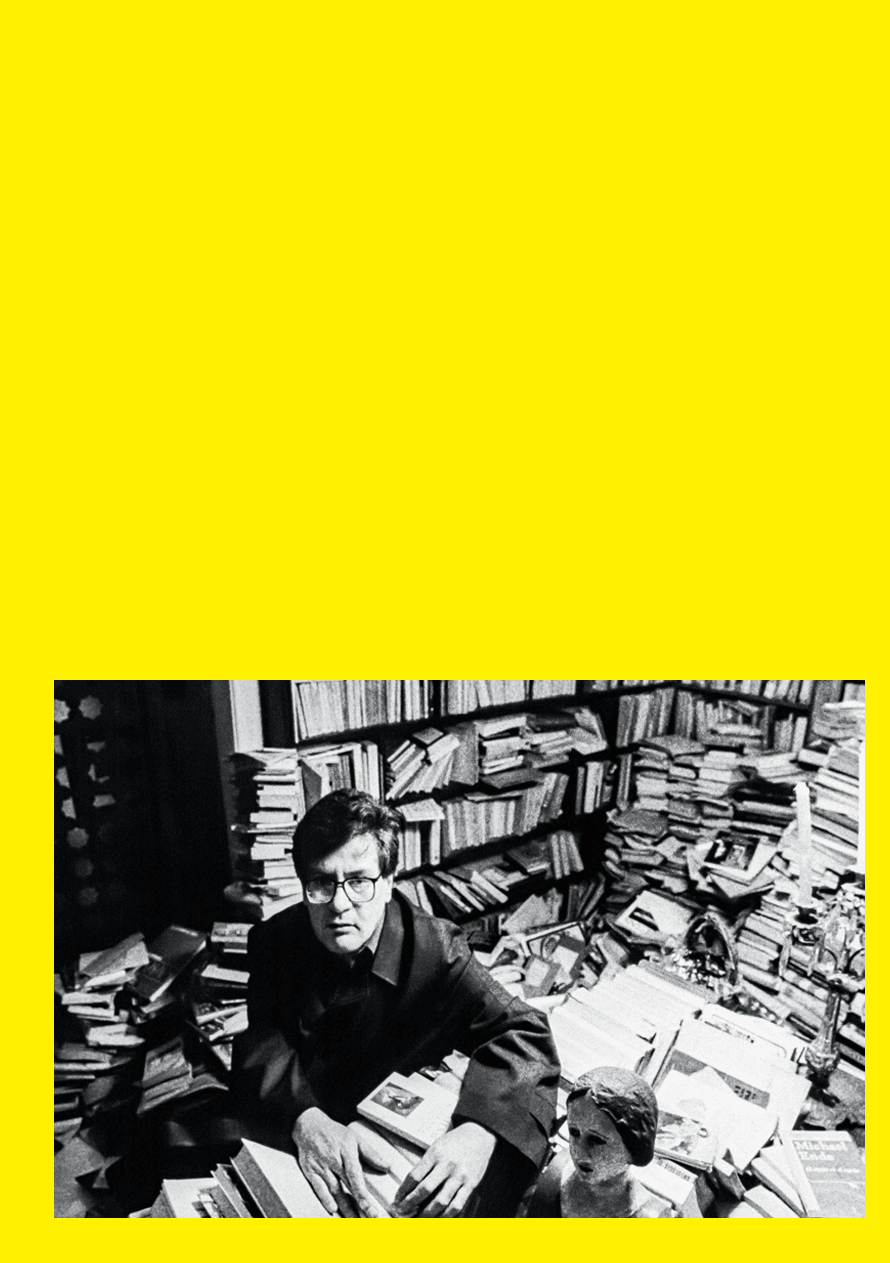

Ulises Carrión (San Andrés Tuxtla, Veracruz, 1941- Amsterdam, Holland, 1989) was a writer, editor, poet and theorist of the international artistic avant-garde. He is considered the most important conceptual artist that Mexico has offered to the world.

He lived in France, Germany, England and Holland. In 1975 he became co-founder of the In-Out Center, a space managed by independent artists in Amsterdam; he also founded the bookstore-gallery Other Books And So, whose purpose was to present, produce and distribute publications that Carrión called “non books, anti books, pseudo books, quasi books, concrete books, visual books, conceptual books...”, since they were not literary texts or related to art, but could be considered a work of art in themselves.

The largest retrospective of his work to date took place in 2016, which was first exhibited at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, in Madrid, and then at the Museo Jumex in Mexico. Although his work is still not widely known in Mexico, it is continuously studied as a cult object in many other countries.

From Berlin, the city where artist Mariana Castillo Deball (Mexico City, 1975) lives and works, she has dedicated herself to relate science, archeology and visual arts to create her own vision of the world. This long process of research has resulted in a body of work that includes installations, sculptures, engraving, photography, performance, publishing projects and a series of artifacts that look into the role of objects to understand identity and the construction of history.

Finding Oneself Outside (2019) was her first individual production exhibited in a museum in the United States, which arrived at the New Museum in New York. Other important exhibitions have been: Petlacoatl (2018), at the Logan Arts Center in Chicago; Pleasures of Association, and Poissons, such as Love (2017), at the Galerie Wedding in Berlin; and ¿Quién medirá el espacio, quién me dirá el momento? (2015), at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Oaxaca.

Her proposal and career have been honored with the Prix de Rome (2004), the Zurich Art Prize (2012), and the Henry Moore Institute’s grant (2012).

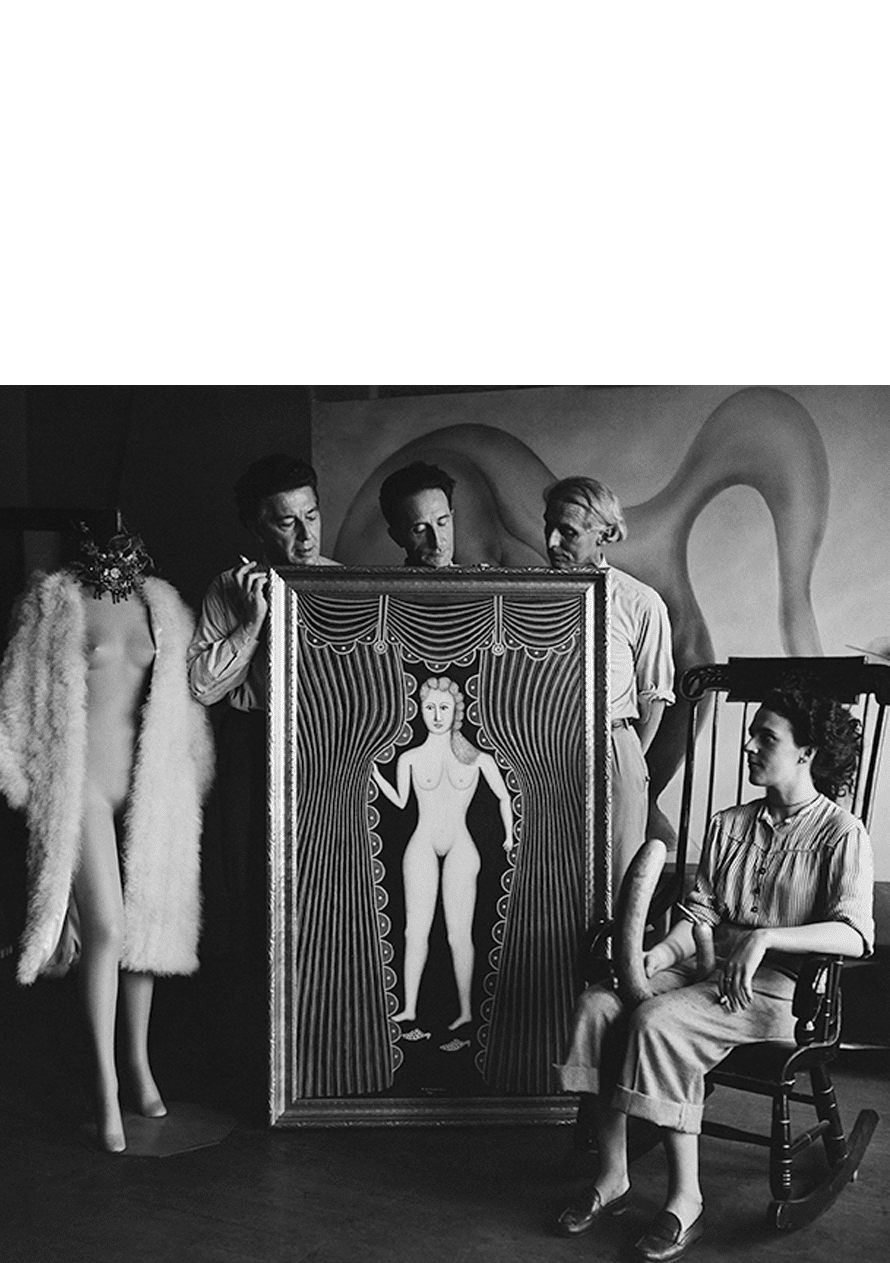

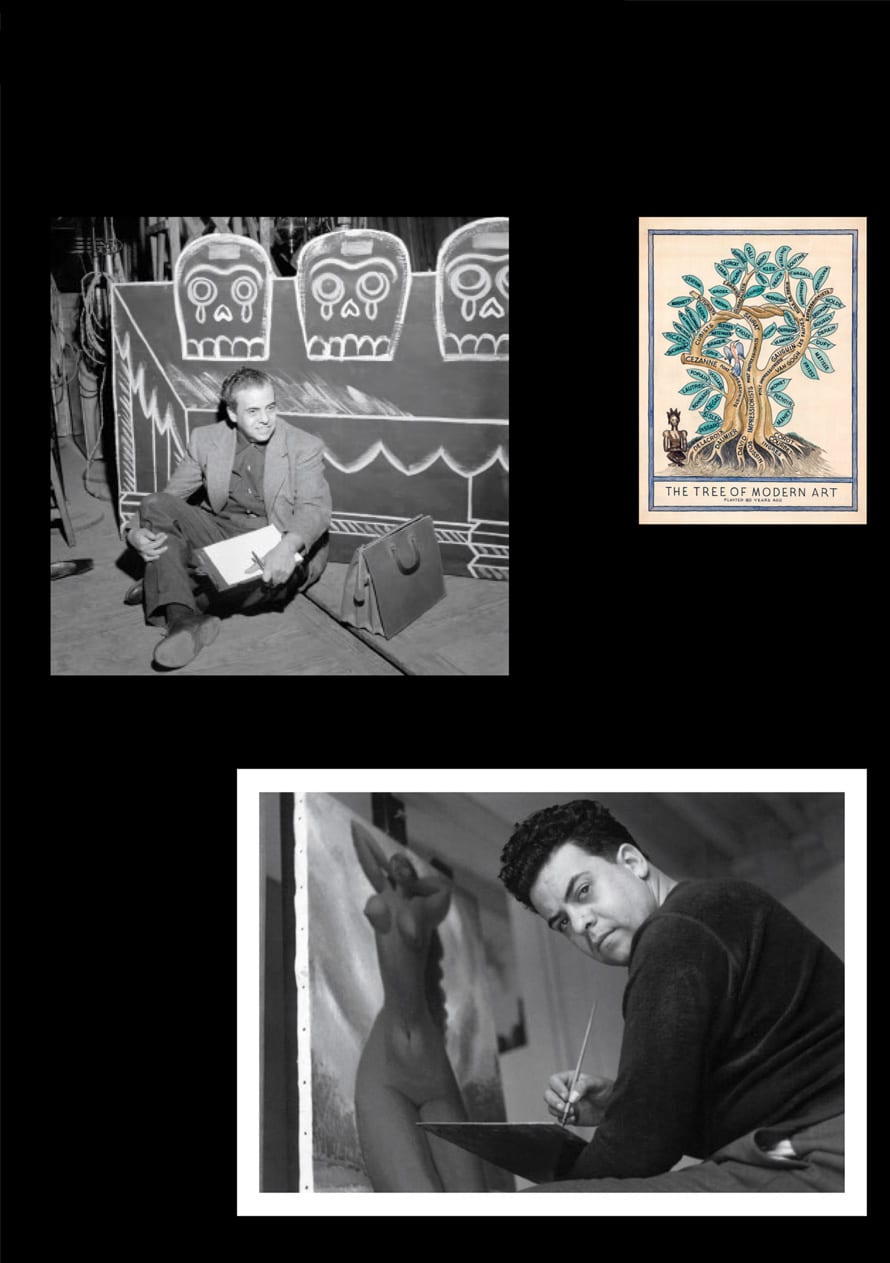

Miguel Covarrubias (Mexico City, 1904-1957) was a caricaturist, painter, anthropologist and cultural animator, whose journey through art ranged from portrait of the people to “satirical praise” caricatures of celebrities, or other topics such as dance promotion.

He began his artistic career at age 14, drawing caricatures for minor publications. At 19 years old, “El Chamaco”, as he was known, got a job at the Mexican consulate and traveled to New York, where he soon met writer and photographer Carl van Vechten, who invited him to publish his first cartoons in Vanity Fair magazine —and later Vogue—, where he worked from 1924 to 1936.

Covarrubias was renowned in the New York circle for his celebrity caricatures and cover illustrations, which earned him worldwide fame. In 1938 he received the Art Directors Club Award for a cover with surrealist style created for Vogue magazine. He also designed theatrical sets, illustrated books and painted, while studying a degree in Anthropology.

He was greatly passionate about art and culture, with multiple artistic interests. On his return to Mexico, in the 1940s, he was appointed director of the Dance Department at the National Institute of Fine Arts (INBA), where he promoted modern dance.

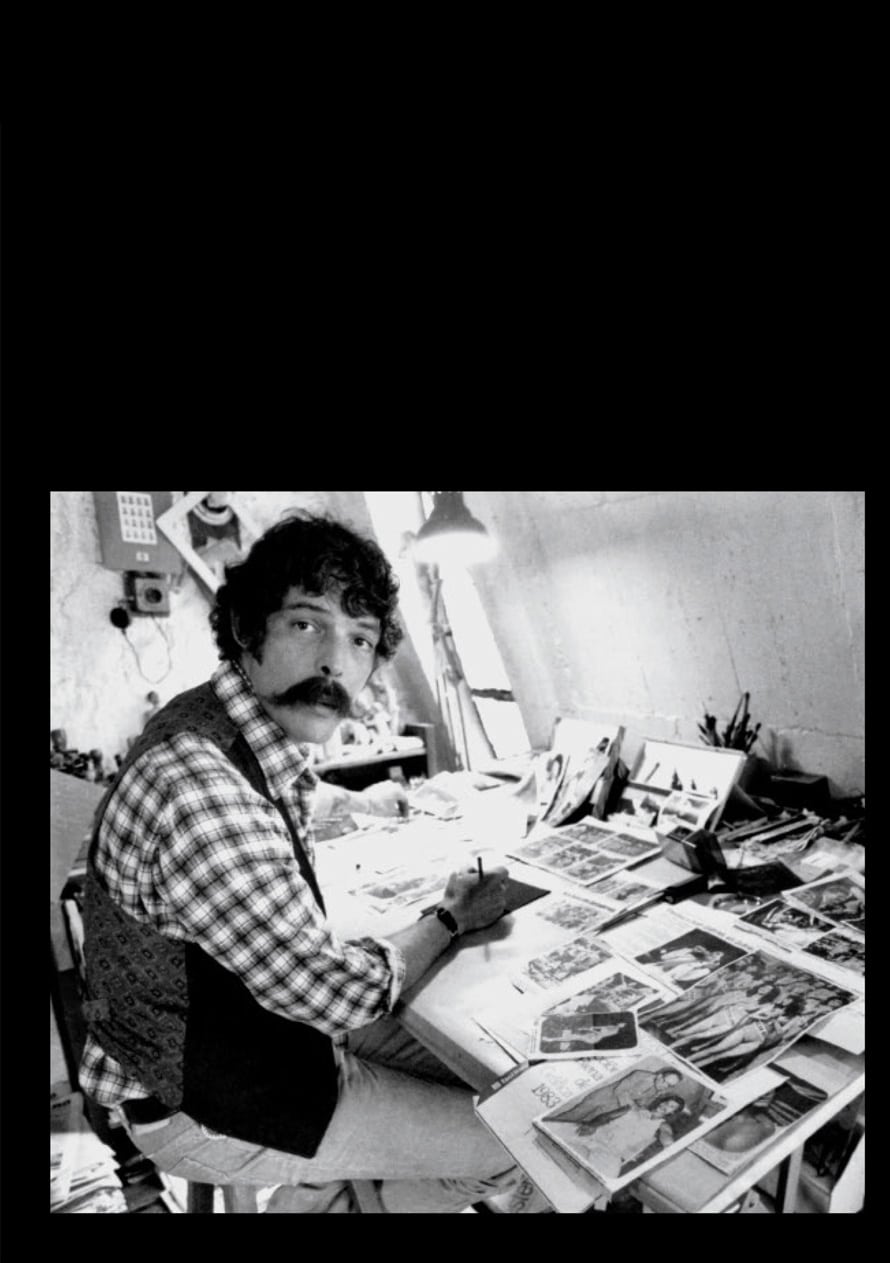

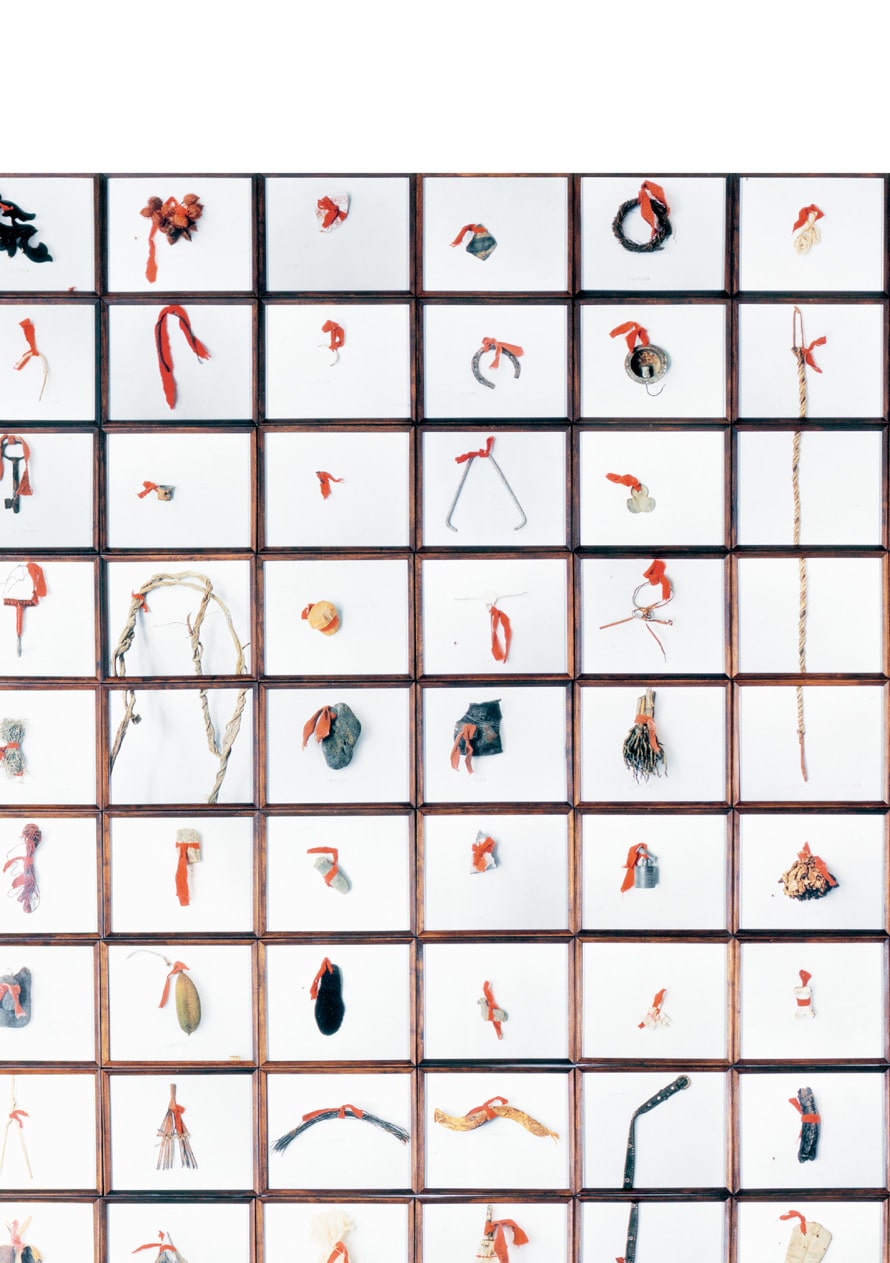

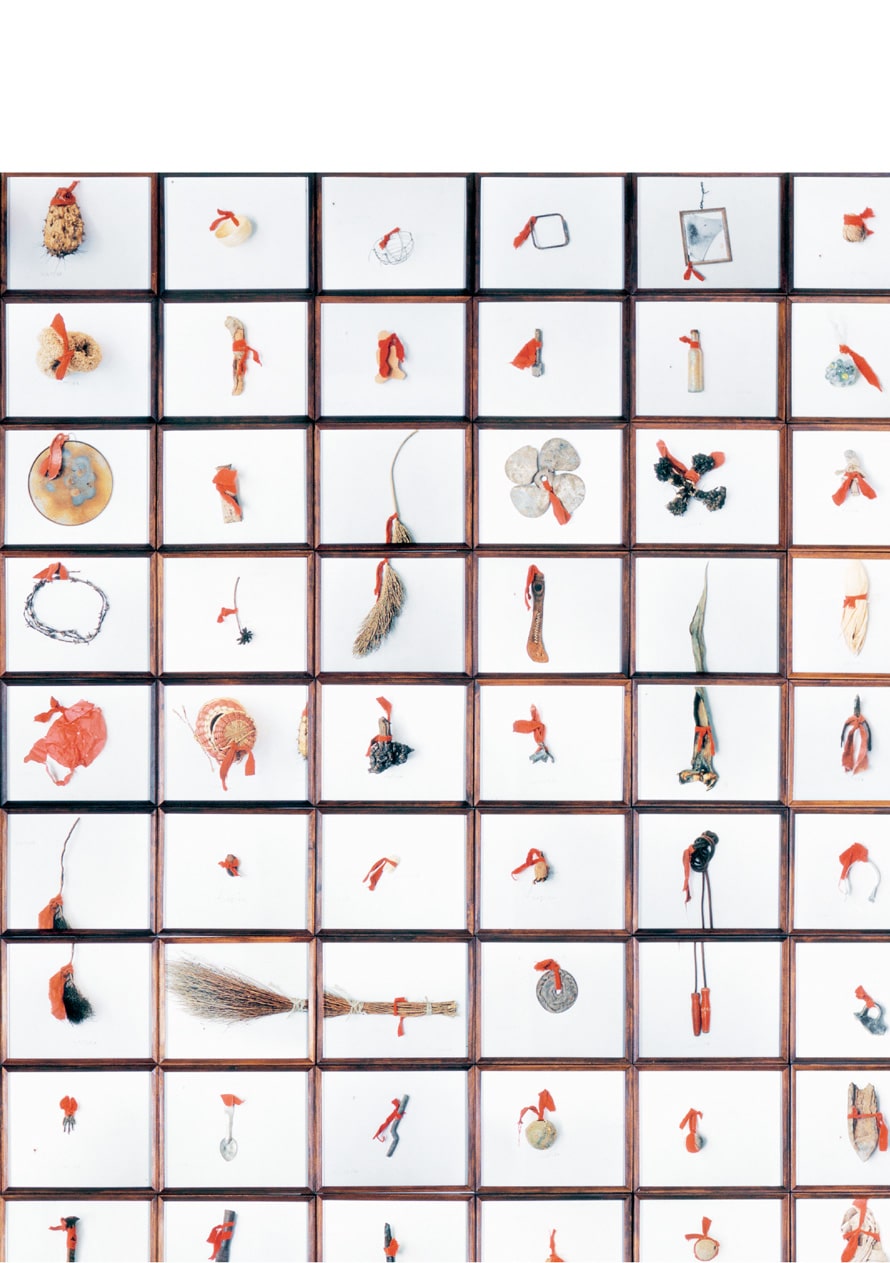

Abraham Cruzvillegas (Mexico City, 1968) debated between becoming a butcher or a singer and opted for art. He studied pedagogy while self-training himself to become a caricaturist. With time and much artistic search, he earned a place as one of the most renowned Mexican artists in the world of contemporary art.

Cruzvillegas speaks of self-construction as a principle of his creative process, where playing and inventive improvisation prevail. Resembling a controlled Diogenes syndrome, his study focuses on the accumulation of all kinds of objects, which he later uses in his works appealing to the chaotic nature of creation.

His work, full of humor and political sense, includes sculpture, painting, drawing, installation and video. He has also cultivated writing and is author of songs and texts that reflect on art, politics and culture.

In 2015 he became the second Latin American artist to occupy the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern in England with his work Empty Lot. He has been awarded the Prix Altadis d’Arts Plastiques (2006) and was the fifth laureate with the Yanghyun Prize (2012).

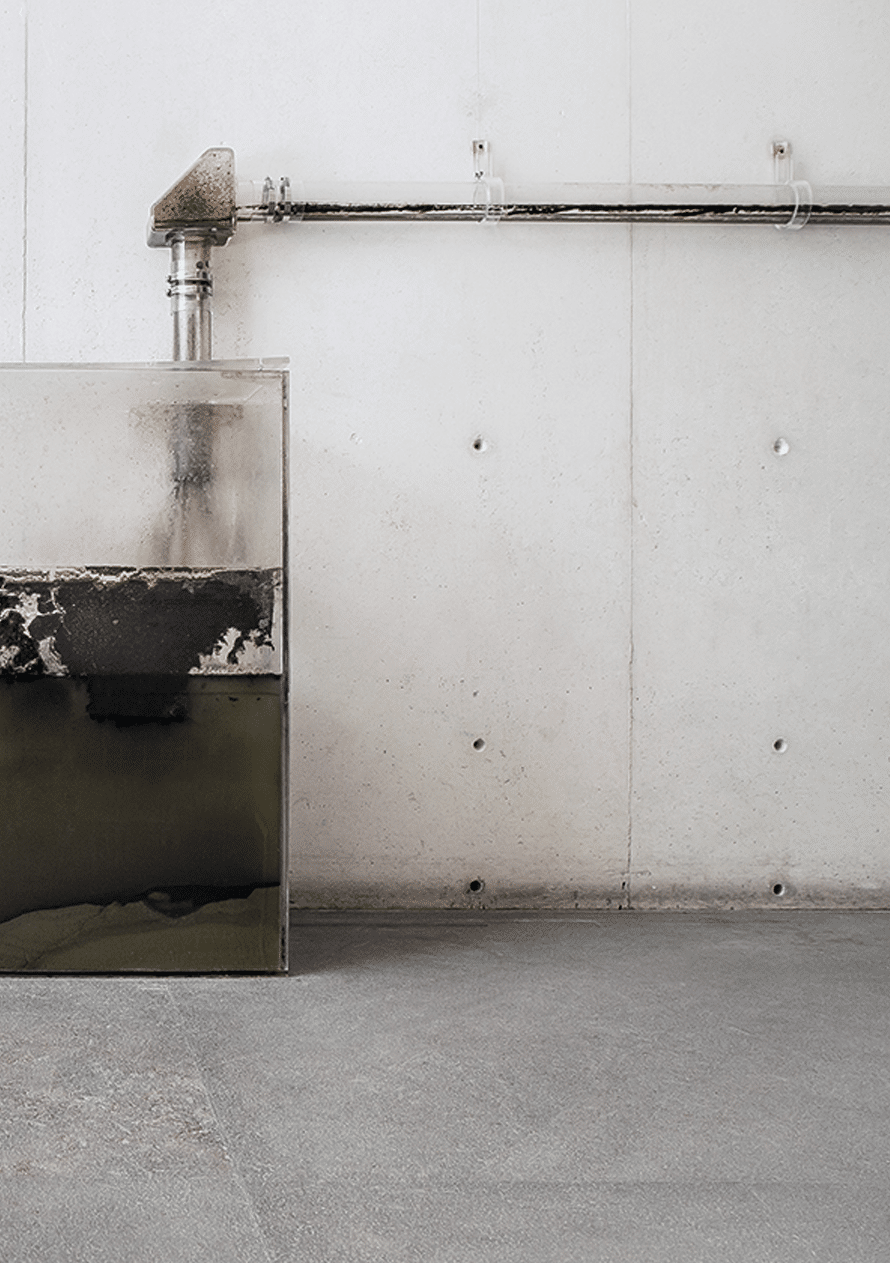

Throughout her career, Minerva Cuevas (Mexico City, 1975) has found the raw material of her work in social and political research. Her disagreements and concerns —especially regarding environmental and ecological issues— have been captured in a proposal that goes beyond the frontiers of art by entering the field of social activism.

Assisted by painting, photography, sculpture, video, installation and public intervention actions, she criticizes and questions power relations and their social links, as well as the use of natural resources and the role of large corporations in food production.

To accomplish this, she resorts to irony, humor and the same tools that power structures use to impose their narrative: objects and images of everyday use, as well as the language of marketing and advertising.

Her work has been exhibited in important museums and galleries, among which are the Museo de la Ciudad de México, Museo Tamayo, Museo Jumex, Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC), the Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin, the Centre Pompidou of Paris, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitechapel Gallery of London.

The interests of Felipe Ehrenberg (Mexico City, 1943-Ahuatepec, Morelos, 2017) shifted naturally from graphics to words, from video to performance, and from galleries —or classrooms— to the street. He was a painter, sculptor, engraver, activist, teacher, diplomat, editor, author, and a pioneer of the neographic technique, mimeography and performance.

In England he was founder of the artistic collectives Beau Geste Press and Polygonal Workshop, with which he supported experimental art and neo-Dadaism. In Mexico he helped found the collective Tepito Arte Acá, where not only did he create and teach but, after the 1985 earthquake, he became involved in the coordination of a program to rebuild the neighborhoods of Tepito and San Jacinto, in Mexico City.

He was awarded the Roque Dalton Medal by the Culture and Science Cooperation Council of El Salvador, in 1987. Among other recognitions, he received the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1976 and the Femirama Prize, in Buenos Aires, in 1968. In 1990, he participated as a resident artist in Nexus Press, Atlanta, where he designed and produced his book-object, the Codex Aeroscriptus Ehrenbergensis.

Helen Escobedo (Mexico City, 1934-2010) is remembered as an essential element in the development of the cultural field and museography in our country. With a vision ahead of her time and an authentic passion for artistic work, she pursued the expansion of art spaces from all trenches, as she was a sculptor, designer, museologist, disseminator and museum director.

A precursor of urban art, she traveled through several countries exploring the renewing character of impermanence: social and political nature of art through ephemeral installations, created with a work team and materials found in each place to expose needs, essences and local problems, whether in Tijuana, San Francisco, New Zealand, Cuba, Jerusalem, London or Prague.

In 1997 she completed an art intervention in a park in Hamburg, Germany, with 101 figures made of straw and cloth going towards the train station in the same way as the Jewish community in the Nazi era. This is how Refugees was born, a series that was followed by Exodus and Los Mojados, interventions that evoked the phenomenon of migration in different cultures.

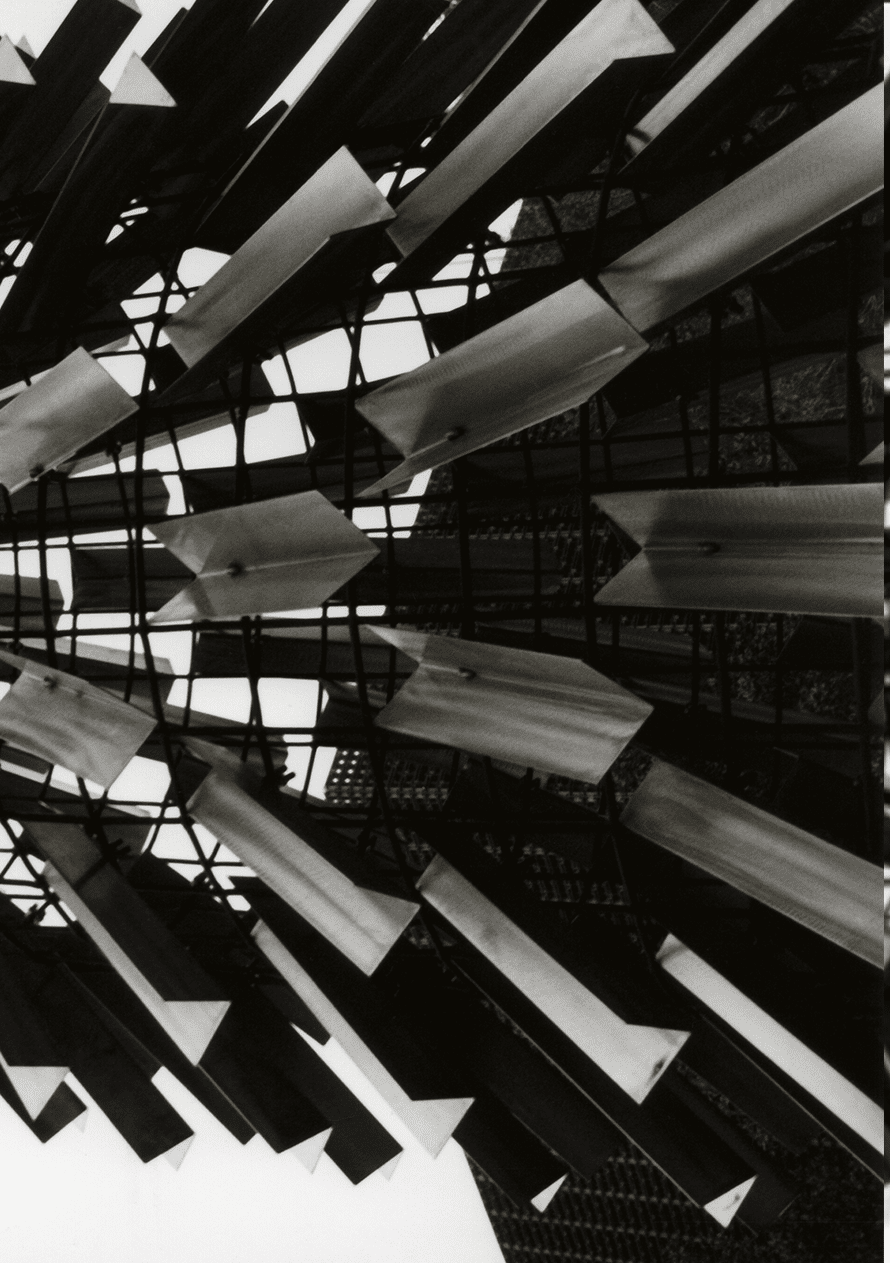

Among her permanent work she participated in the collective creation of the UNAM’s Espacio Escultórico; additionally, her sculpture “Puertas al viento” can be seen along the Route of Friendship, in Mexico City.

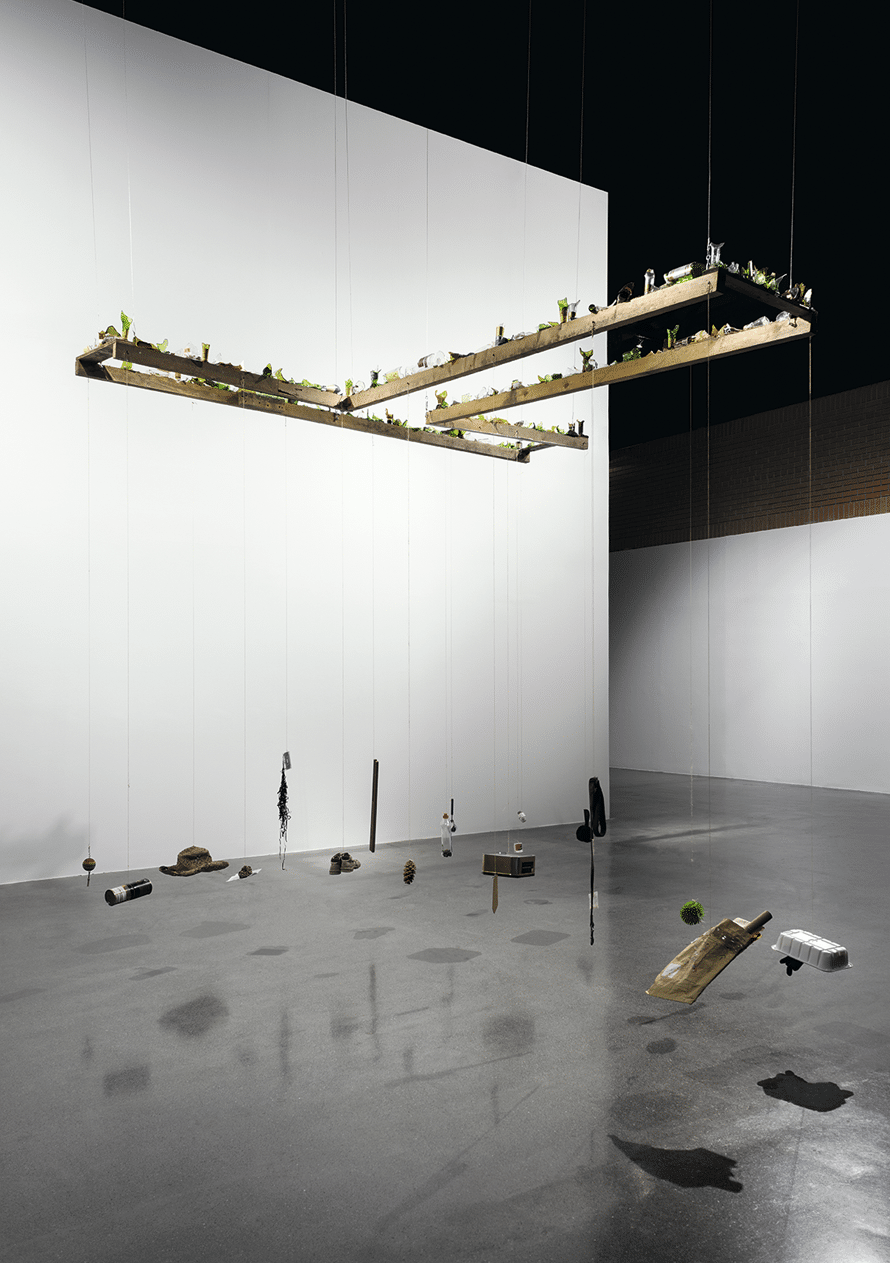

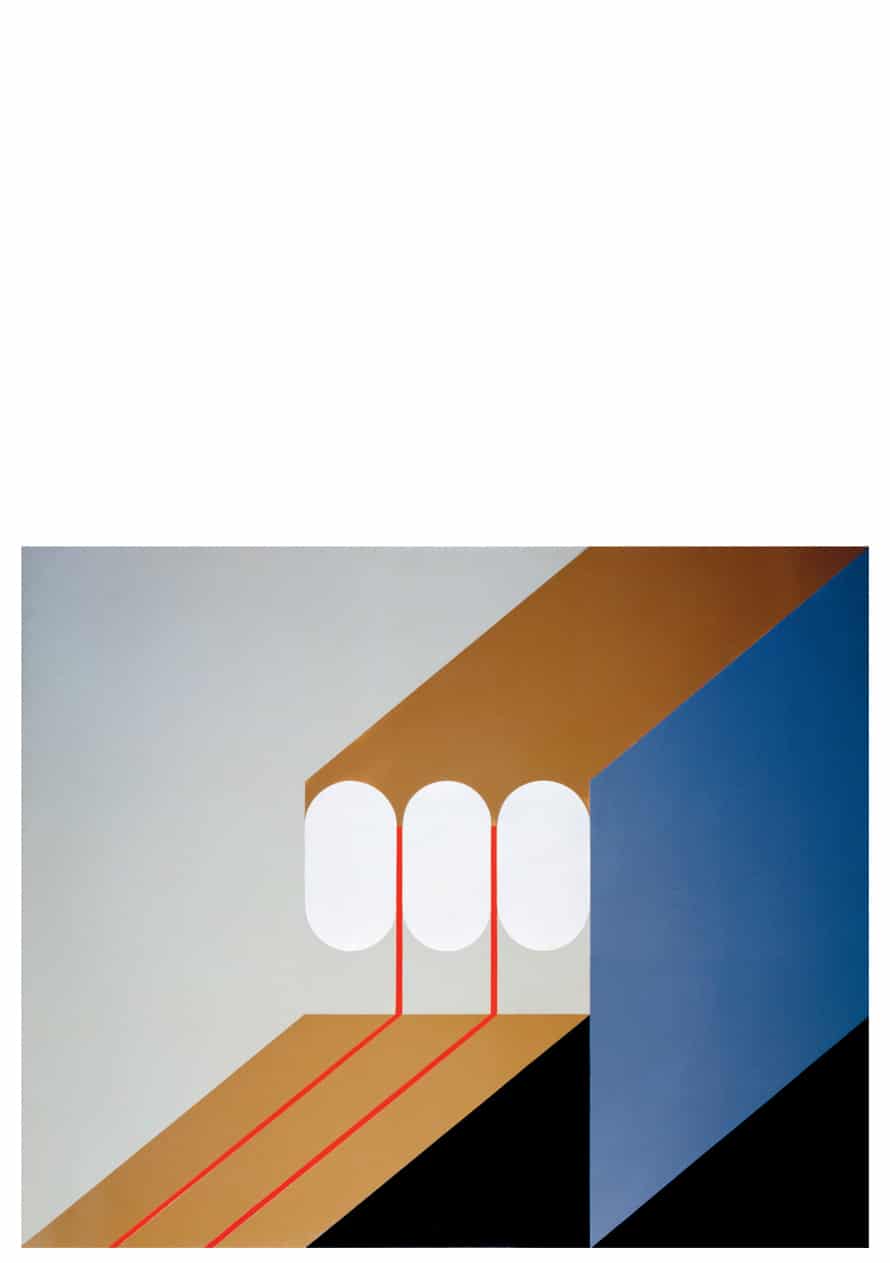

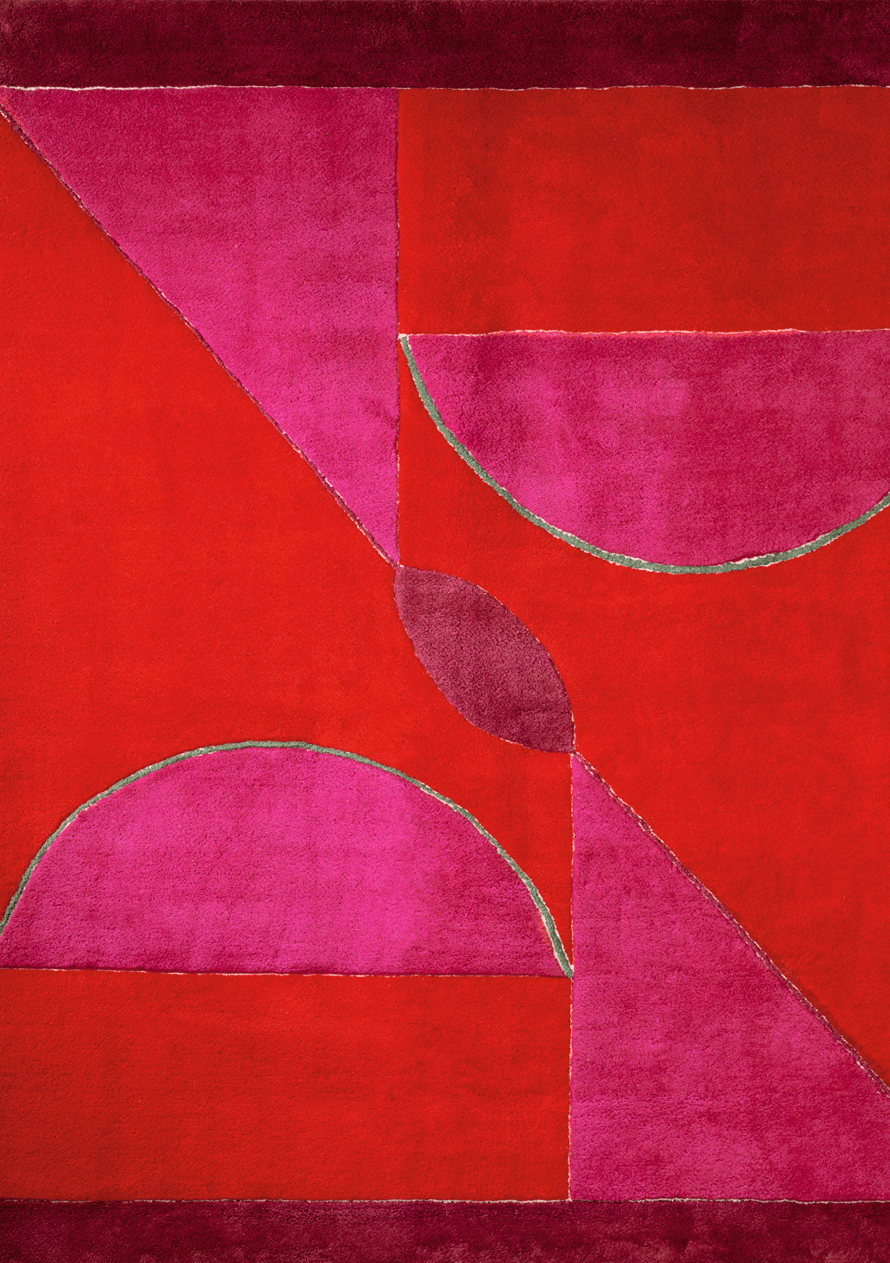

Artist born in Valparaíso, Zacatecas, in 1928; pioneer of abstract art in our country and an essential member of the Rupture Generation, a movement of abstract artists openly confronted with the nationalist tradition of the Mexican School of Painting.

He studied at the National School of Painting, Sculpture and Engraving “La Esmeralda”; at the UNAM’s National School of Plastic Arts; at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and the Académie Colarossi, both in Paris.

Felguérez started out in artistic life as a sculptor in Paris, being a pupil of cubist artist Ossip Zadkine. He made his first solo exhibition at the French Institute for Latin America in Mexico City in 1954, and in 1955 he won his first sculpture prize at the Casa de México in Paris.

His pictorial and sculptural production is vast and is distributed inmuseums and private collections in Mexico and abroad; he also has more than 50 murals and sculptures in public spaces. In recognition of his career and artistic contribution, in 1998 the Manuel Felguérez Museum of Abstract Art was founded in Zacatecas, whose collection was largely donated by the artist himself.

Throughout his career he has received the French Government Scholarship (1954); the Second Painting Prize in the First Triennial of New Delhi, India (1968); the Grand Prize of Honor at the 13th São Paulo Biennial in Brazil (1975); the Guggenheim Fellowship (1975); and the National Arts Award in Mexico (1988).

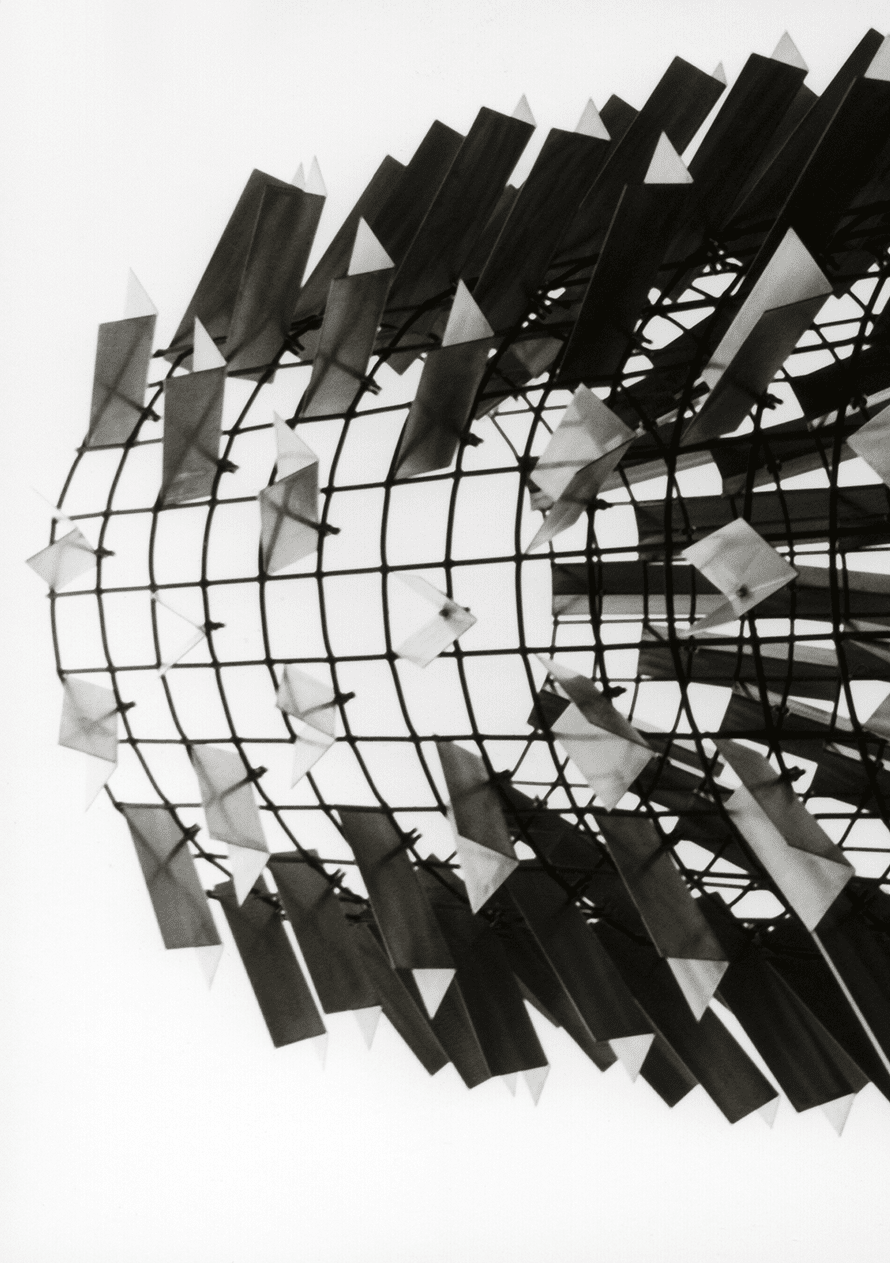

Architect, sculptor, painter, poet and art historian, Mathias Goeritz (Gdańsk, 1915-Mexico City, 1990) is one of the main figures of Mexican plastic art modernization. He is credited along with Luis Barragán for the invention of “emotional architecture”, a movement that emerged in Mexico during the 20th century that promotes the use of color, lighting, water and vegetation to create harmony.

He fled Germany in 1936 after the establishment of National Socialism, partly because of his Jewish origin, and partly because this ideology considered that modern artists represented a danger for the government.

He arrived in Mexico in 1949, as a visiting scholar of the recently founded School of Architecture of the University of Guadalajara, Jalisco. There he created a design workshop in which he shared the teachings of the Bauhaus. His workshops in this and other universities had an important influence on contemporary art.

Among his most significant works are El Museo Experimental El Eco (1952) in Mexico City; and the Torres de Satélite (1958), created in collaboration with Luis Barragán and painter Jesús Reyes Ferreira. On the occasion of the 1968 Olympic Games, he promoted the creation of the Friendship Route, an urban sculptural circuit, located in Mexico City, which integrates the work of more than a dozen foreign sculptors who represented several countries.

Goeritz’s creative evolution can be seen in a body that, in addition to his architectural work, includes drawings, models, photographs, sculptures and paintings, as well as his literary search. He wrote poetry and the Emotional Architecture Manifesto published in 1953, among other things.

Silvia Gruner (Mexico City, 1959) is a multidisciplinary artist whose work, of performative roots, alternates video art, photography, installation and Super-8 film. She studied Plastic Arts at the Massachusetts College of Art in Boston, and at the Betzalel Academy of Art and Design of Jerusalem.

Throughout more than three decades of work she has focused her practice on a poetic exploration of the body-identity relationship, which seeks to confront the traditional role played by different artifacts or environments in the collective imaginary based on the body, insisting on the private and collective character of its relationship with the world.

Her work has been shown in museums and galleries around the world, of which the most remarkable are the Hispanic Society of New York; the Museo Amparo of Puebla, Mexico; the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, in Madrid; the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego; the Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wilfredo Lam, in Havana; the Museo del Barrio, in New York; and the Second Biennial in Johannesburg, South Africa, among others.

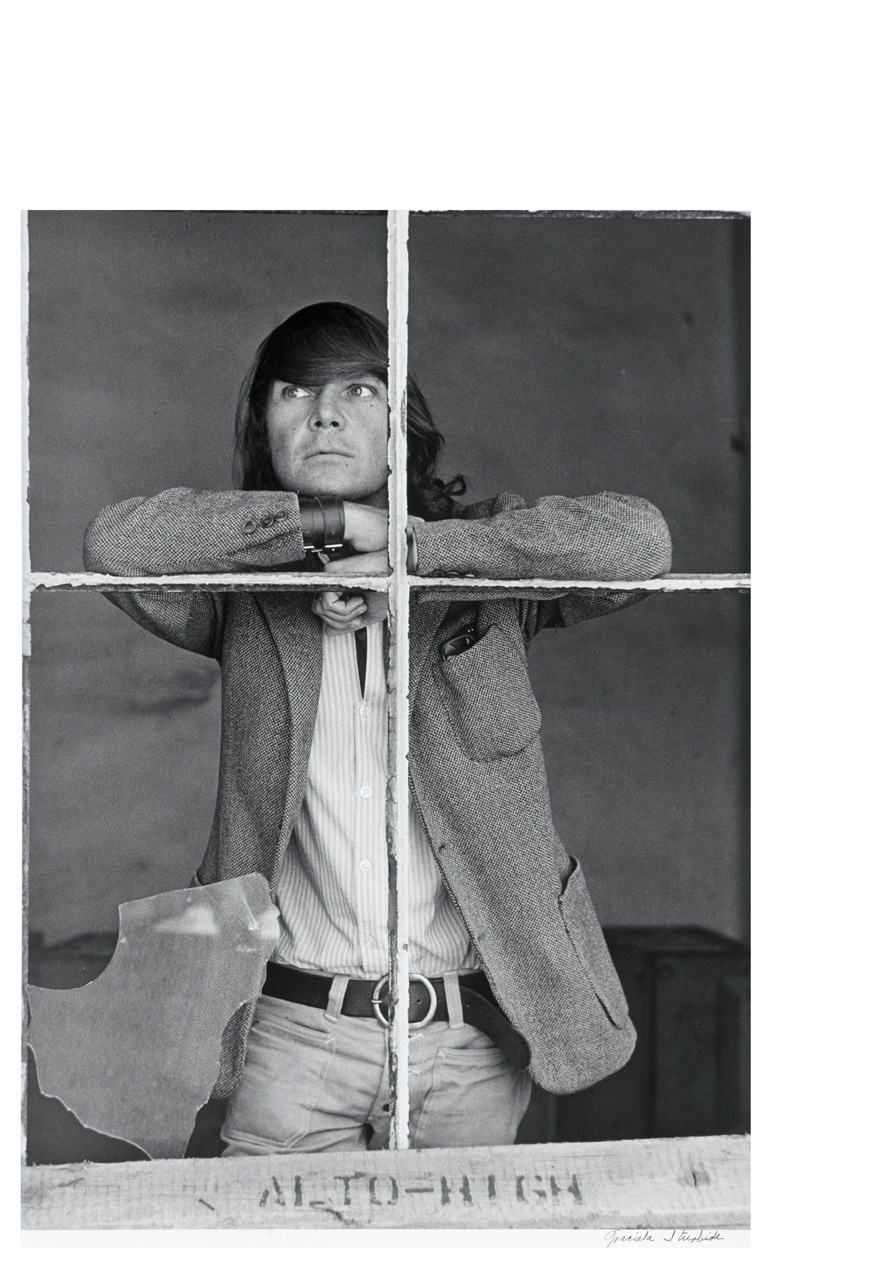

“A camera is an excuse to get to know yourself and the world”, says Graciela Iturbide (Mexico City, 1942), who in 2008 won the Hasselblad Award in Sweden, considered the Nobel Prize in photography.

In 1969 she entered the UNAM’s University Center for Film Studies, hoping to become a filmmaker. However, along her path she came across Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s photography chair, which she attended, soon becoming his assistant. For just over a year she accompanied the legendary photographer in his travels around the country and developed a form of observation that soon specialized in portraying indigenous communities of Mexico.

Graciela Iturbide has known how to eternalize reality without impostures; she allows life to happen in front of her camera. Her favorite photo is Mujer ángel (1979), a gift from the Sonora Desert, in which an unknown Seri woman heads quickly towards the scrubland holding a tape recorder in her hand.

She is the author of several books, among which stand out: Those Who Live in the Sand (1981) and Juchitán de las mujeres (1989). She has been invited to work in Germany, India, Madagascar, Hungary, Cuba, France and the United States.

The day the real history of Mexican painting of this century is written, the name of María Izquierdo will be a small but powerful center of magnetic radiation.

Octavio Paz

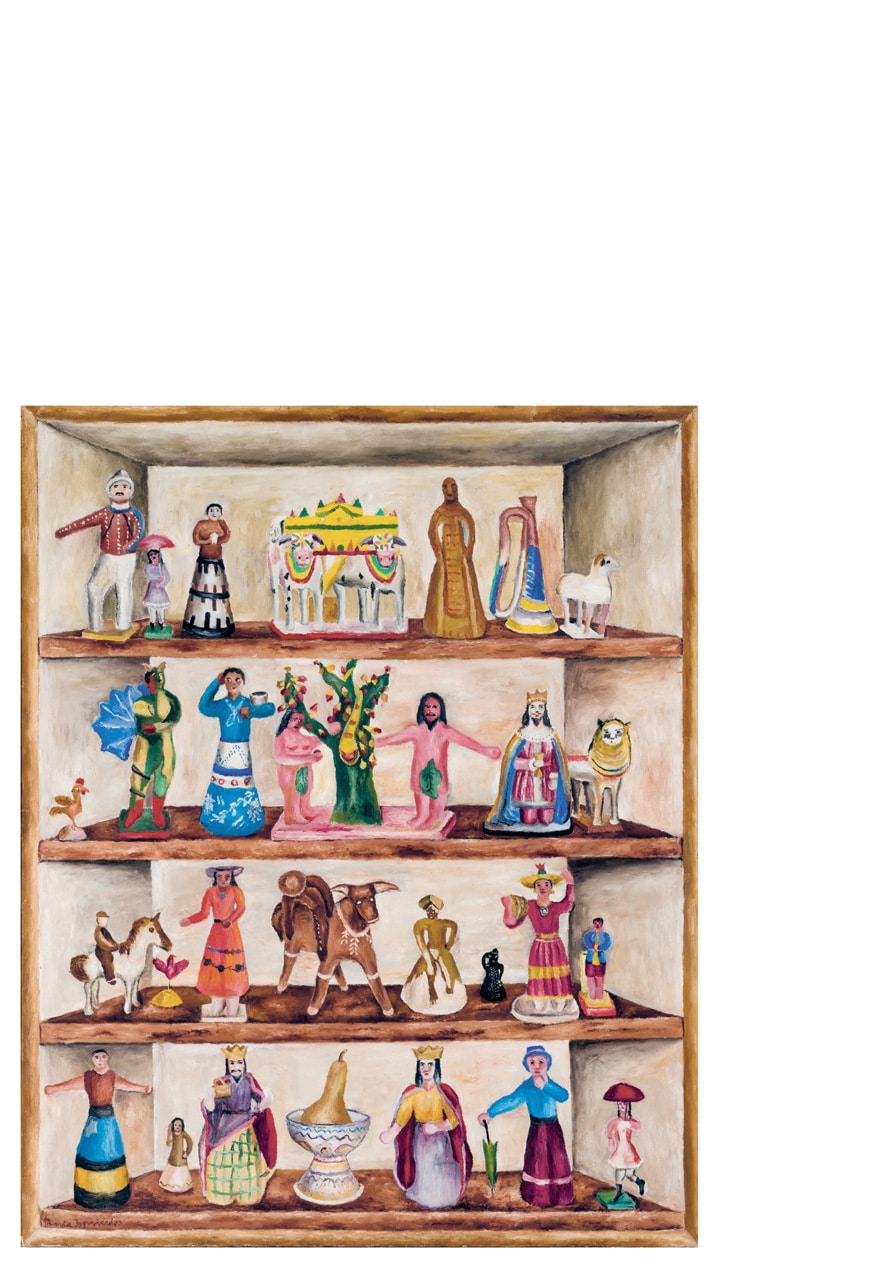

Born in San Juan de los Lagos, Jalisco, María Izquierdo (1902-1955) was the first Mexican painter to exhibit her work in the United States, first at the Art Center in New York, in 1930, and later at the Museum of Modern Art in the same city, in the exhibition Mexican Arts, achieved against all odds and avoiding the prevail-ing machismo of the time.

“It is a crime to be a woman and have talent”, she said after the disappointment she experienced in 1945 when she was hired to paint a 200 square meter mural and was later dismissed from the project when some important muralists of the time intervened, opposing that the commission had been granted to a woman.

But sabotage did not stop her, she became actively involved in the defense of women’s rights, she painted monumental murals, such as La música and La tragedia (1946), and continued painting even after being paralyzed by hemiplegia on the right side of her body in 1948. Her work, full of color and dream worlds, sought to be “an open window to the human imagination” and has been declared cul- tural heritage of the nation.

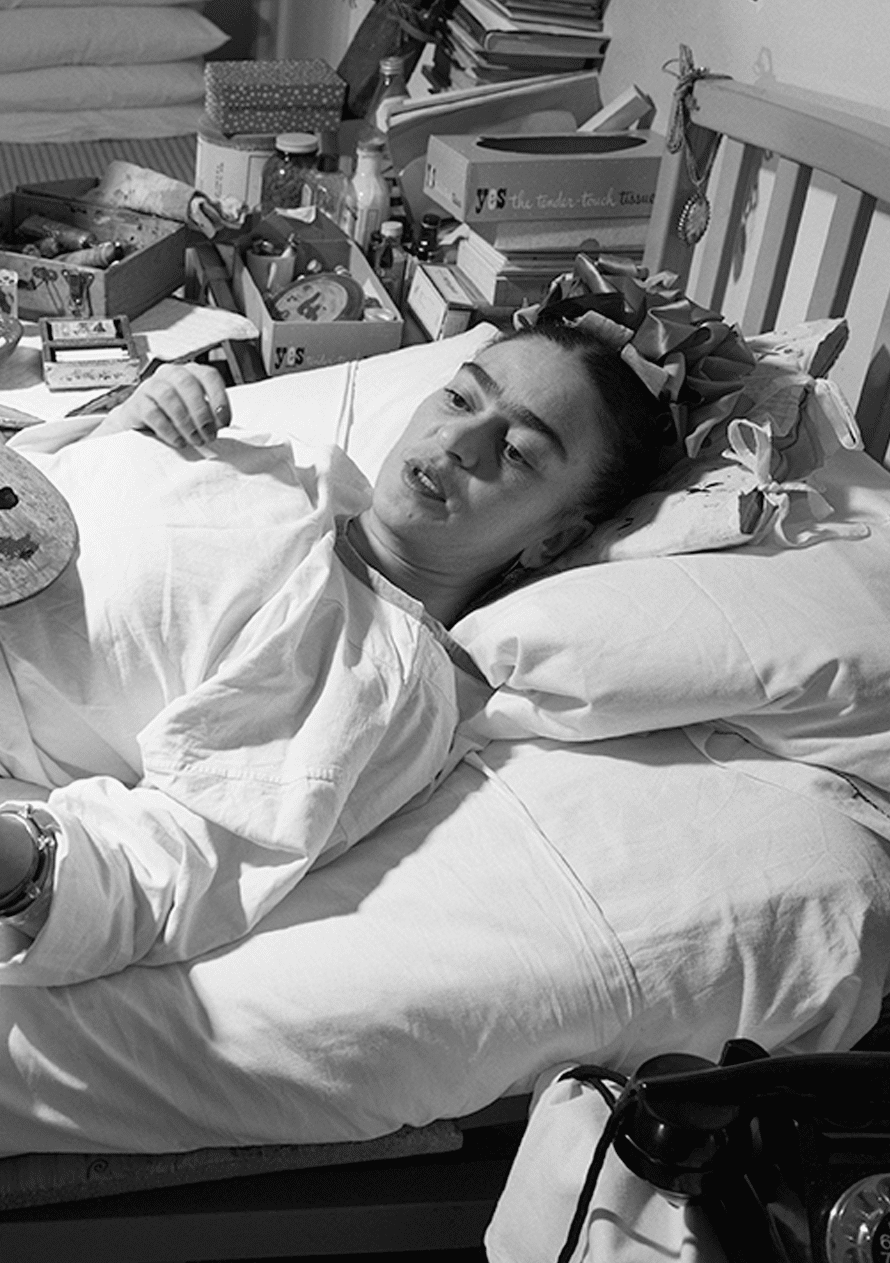

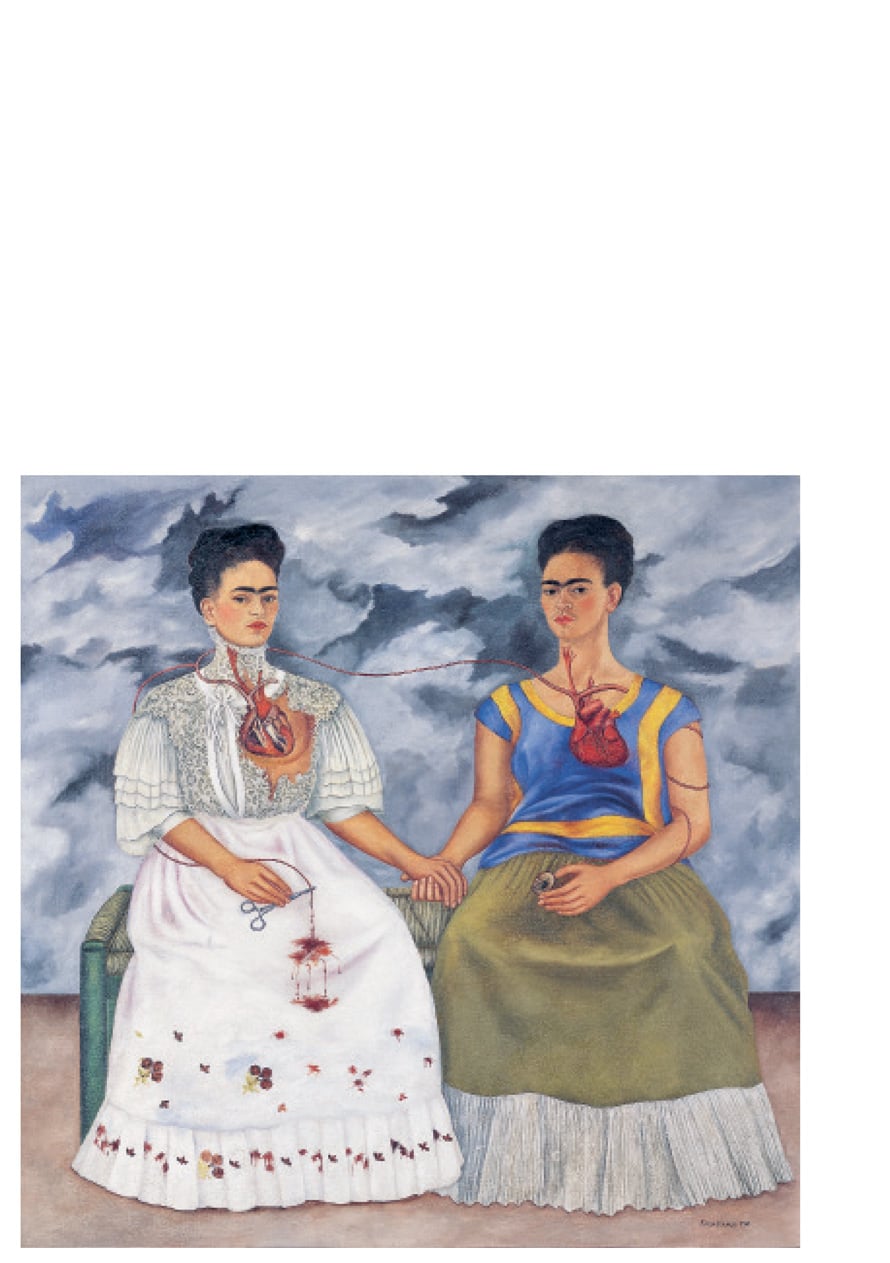

Everything about Frida Kahlo (Mexico City, 1907- 1954) has been written, confirming, almost to the point of exhaustion, that she is the most famous Mexican artist in the world. For many she could even be the most famous among all the art figures that have become icons beyond their work.

Not even Frida, who painted her face in more than fifty self-portraits, could have imagined the extent of the infinite mirror that the current “Fridamania” represents. Everything about her is important: her historical moment, the temperament of a woman who knew how to make herself seen in an environment of macho giants, her political tendencies, the controversy of her relationships and love affairs, her painting —which André Breton defined as “A ribbon around a bomb”—, her writing, her phrases, her dressing style, her character and entire personality that have become an object of popular appropriation present in all kinds of memorabilia.

In 2018, the exhibition Making Her Self Up at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London broke record number of visits, just on the first day it sold more than 20 thousand tickets. In that same year she became the first artist that Google Arts & Culture presented in a 360-degree retrospective a journey around her house. Over 800 images of paintings, drawings, sketches, works of art, videos and interactive stories are available to users, who can access them through a mobile app.

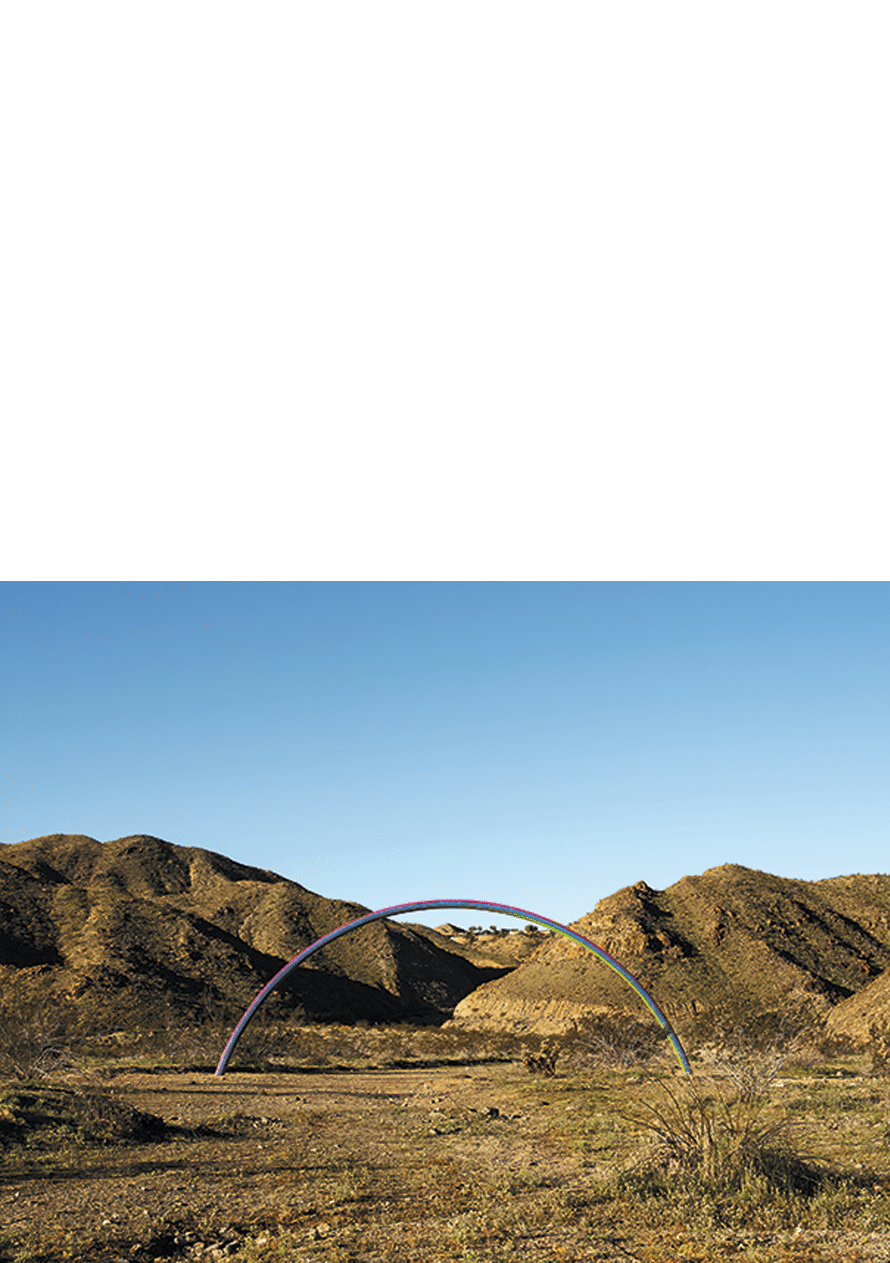

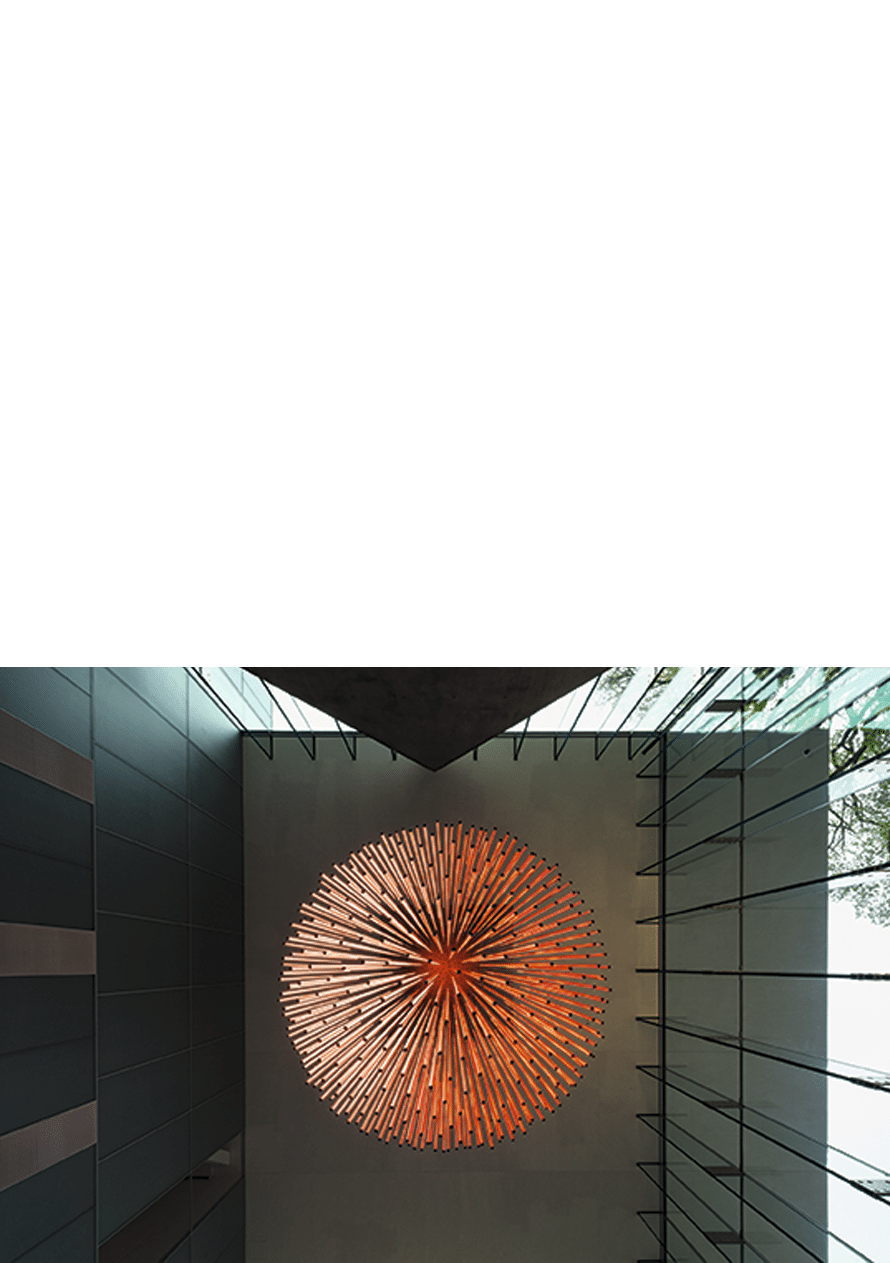

The uniqueness of Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s work (Mexico City, 1967), which combines technology, architecture, installation and theatricality, has earned him a place among the electronic artists that attract the most attention in the field of contemporary world art.

His proposals are ephemeral and experimental, divided in two lines of work: the production of public art —street and square interventions that integrate light and sound— and the work for museums, presented in solo exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, among others. In both cases, the development of the pieces is always determined by the relationship with the public. In 2015, he presented Pseudomatismos at the University Museum of Contemporary Art (MUAC), an exhibition that covered 23 years of audiovisual production, including pieces of interactive video, robotics, computer surveillance, photography and sound installation.

Among his “Relational Architecture” works are Solar Equation, Sandbox and Body Movies, which have traveled to countries such as Austria and New Zealand; in addition to commissioned installations in cities including Rotterdam, Lyon, Tokyo, Dublin, Vancouver and Abu Dhabi.

In 2007 he was chosen to reactivate the Mexican presence at the Venice Biennale after an absence of more than 50 years. In the following editions, the Mexican Pavilion has hosted artists like Ariel Guzik, Teresa Margolles, Tania Candiani and Pablo Vargas Lugo, among others.

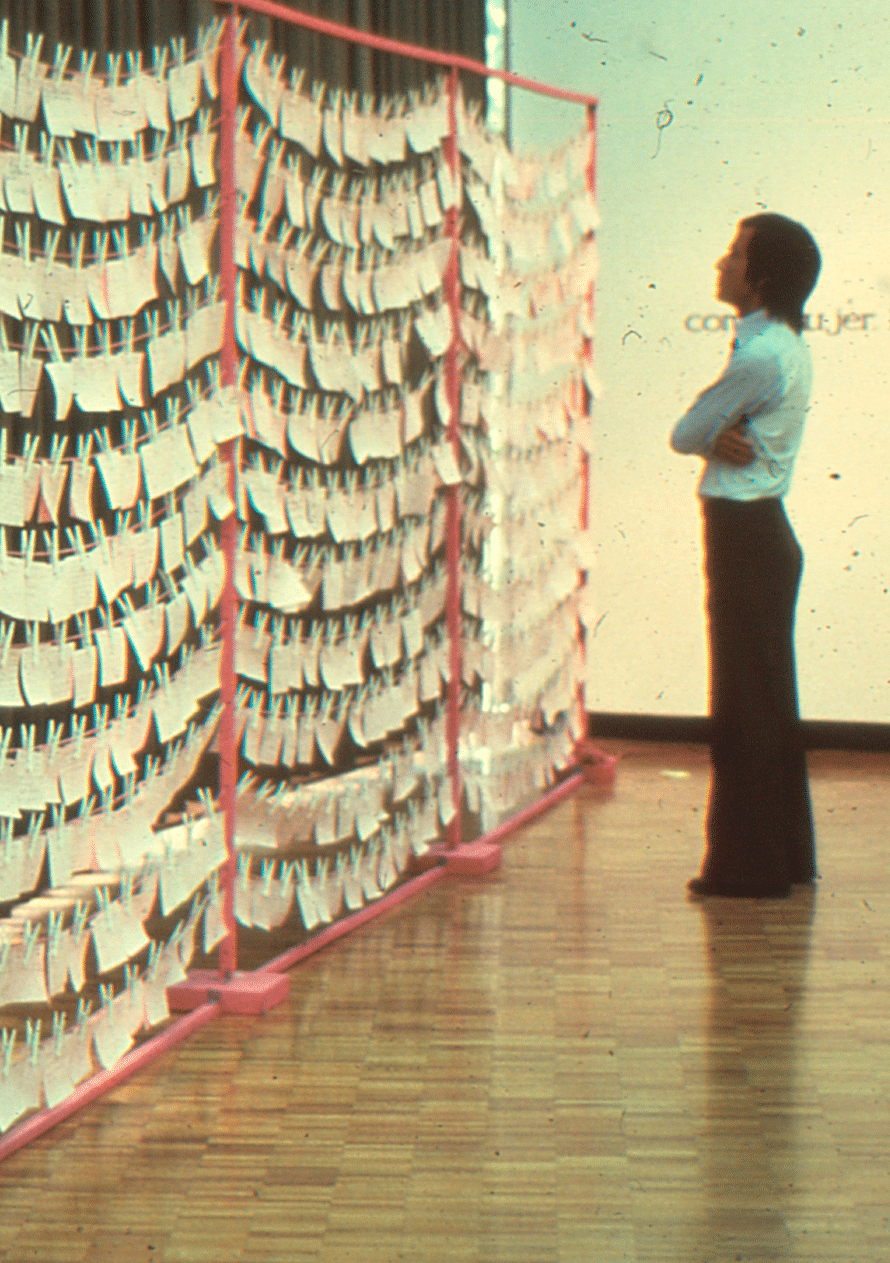

Mónica Mayer (Mexico City, 1954) is a pioneer of feminist art and performance in Mexico and Latin America. As an artist, woman, mother and human being, one of her most important battles has been against invisibility, therefore her proposal insists on building narratives that transform the image historically imposed on women.

Together with Maris Bustamante, she founded the first feminist art collective in Mexico in 1983: Polvo de Gallina Negra. The most famous project of this group was MADRES!, an exploration of motherhood for which both artists became pregnant to observe the experience from a sociological point of view. Part of this initiative included the experiment “Mother for a day”, which entailed a dozen men carrying an artificial belly, among the participants was journalist Guillermo Ochoa, who performed it live on national television in 1987. Notes and collected material have been presented in venues such as the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, in Spain.

In 1989, along with Víctor Lerma, she created Pinto mi raya, a conceptual art project that includes an important archive resulting from research on Mexican contemporary art that began in 1991 and that, to date, includes more than 200 thousand articles.

Her work has been presented in important international exhibitions such as WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution, in the United States and Canada, or La Batalla de los Géneros at the Centro Gallego de Arte Contemporáneo, among others.

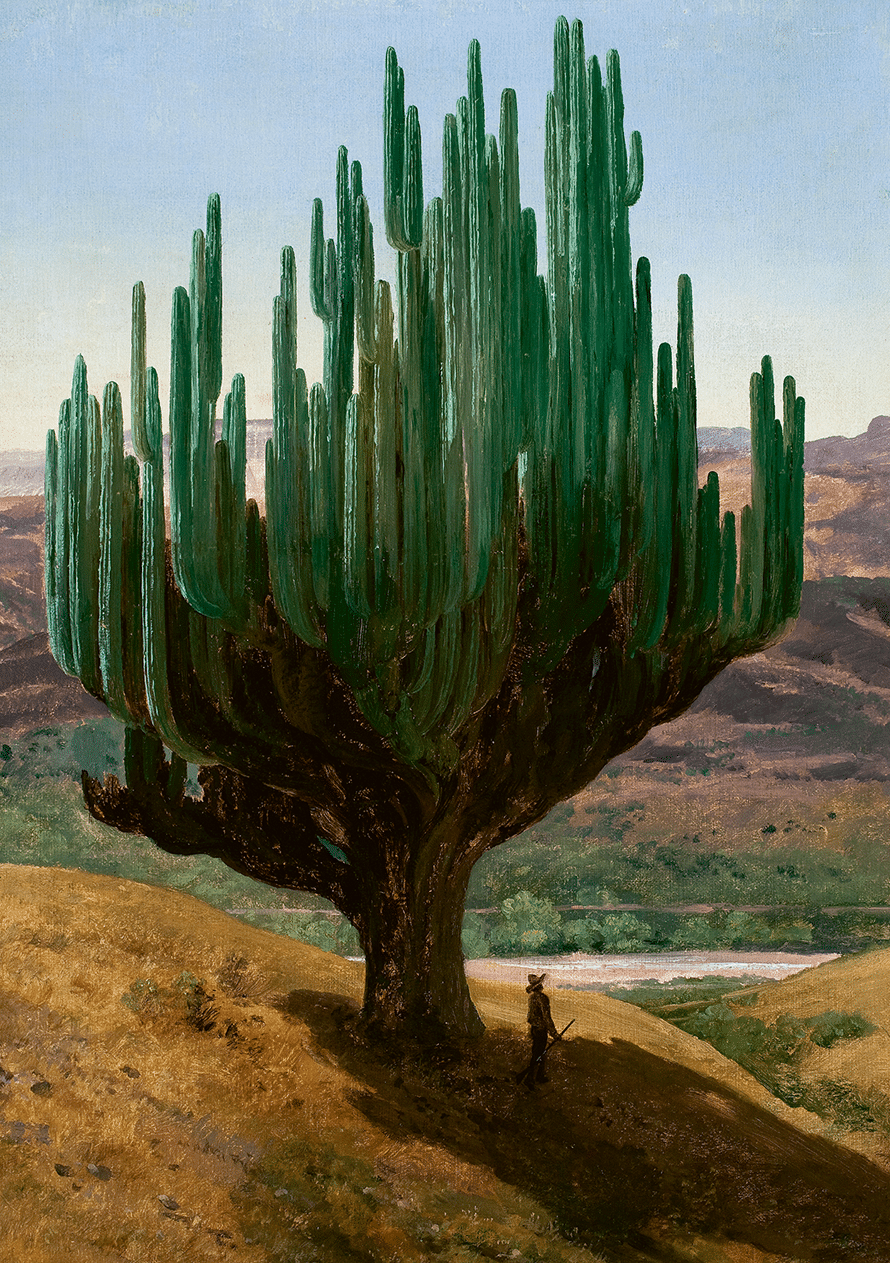

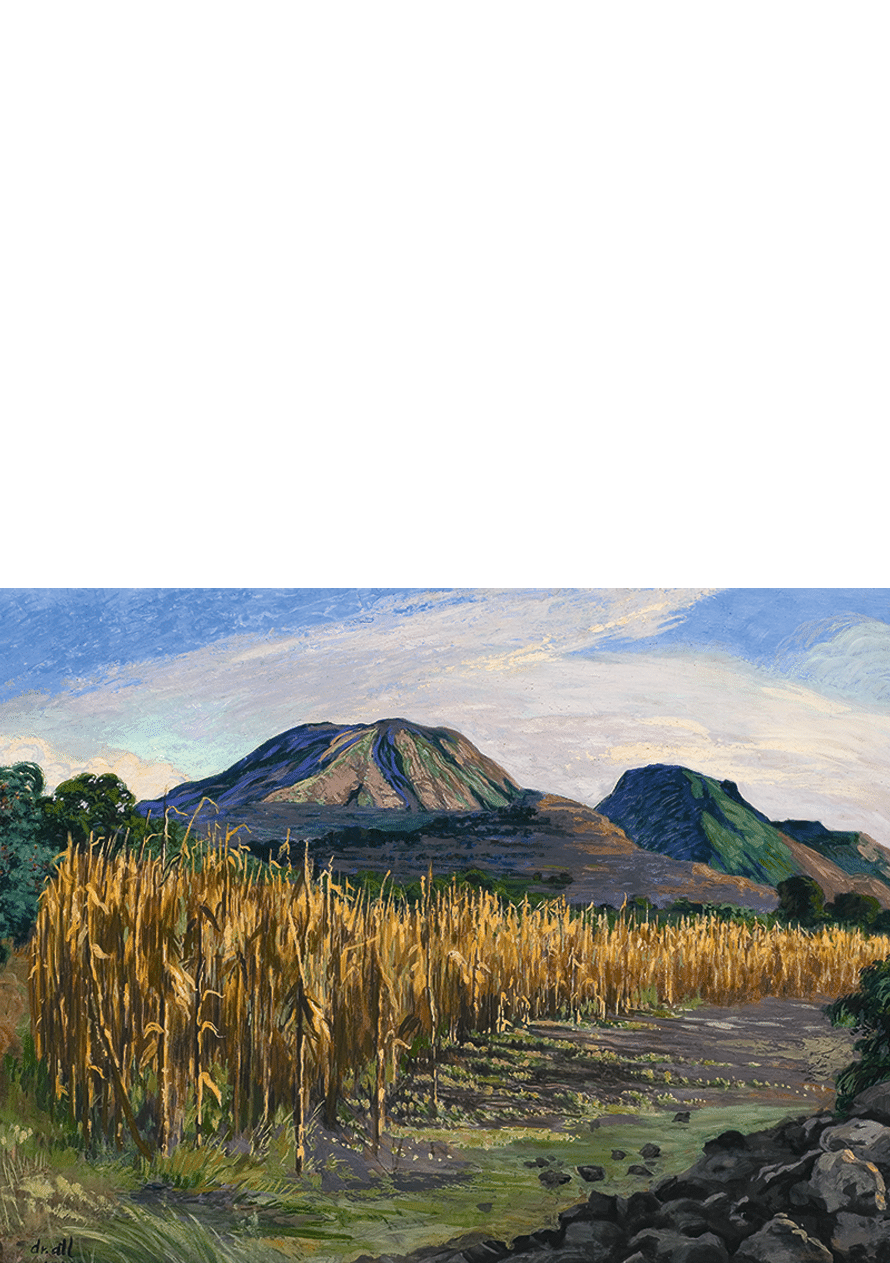

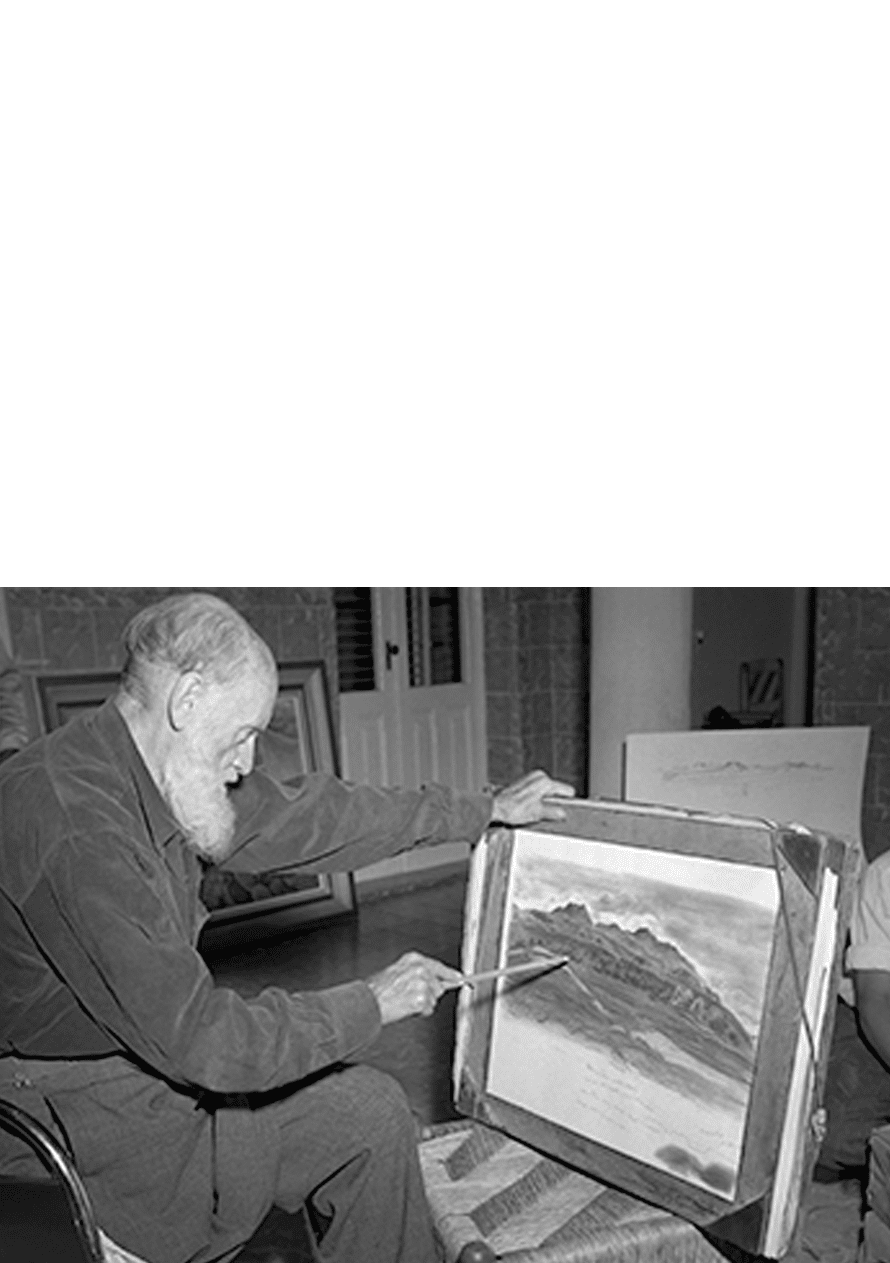

Gerardo Murillo Cornado (Guadalajara, Jalisco 1875–Mexico City 1964) changed his name in 1912, after facing a deadly storm while traveling in an ocean liner. In order to honor the of power of water, he called himself Atl, which means water in Nahuatl. He was a prominent landscaper and teacher of the mexican muralists.

Diego Rivera wrote: “He taught the youth insolence, wrote prose and poetry, and was an expert on volcanoes, botanist, miner, herbalist, astrologist, magician, anarchic materialist, totalitarian [...], he edited newspapers, organized red battalions, looted churches, invited beautiful ladies to tea at the sacristies, and gathered around him a group of young artists of greater value at that time”.35

His training covered studies in Philosophy at the University of Rome, Law at the Sorbonne in Paris, and was filled with Parisian artistic influences for his pictorial work. In the San Carlos Academy, in Mexico, he was known as the “agitator”, because he questioned traditional teaching methods emphasizing popular art. He developed a special technique called “Atl colors”, with which he made pigments based on resin, wax and oil, that gave them a unique consistency capable of painting even on rocks.

Yoshua Okón (Mexico City, 1970) defines his artistic production as “a series of near-sociological experiments executed for the camera, blending staged situations, documentation and improvisation, and questioning the perceptions of reality and truth, individuality and morality”.

Harsh and irreverent, he takes advantage of art as an opportunity to create a critique that bothers the viewer and breaks the state of passive consumption, leading to reflections on issues such as migration, racism, slavery, globalization and power.

In 2018, the University Museum of Contemporary Art presented Colateral, a two-decade review of his work, which included series such as Risas enlatadas (2009), where he alludes to the processes of mechanization and slavery in globalization, and Freedom Fries: Naturaleza muerta (2014), where he questions the era of capitalist consumption.

In response to the lack of venues to exhibit contemporary art, he founded La Panadería in 1994, a space coordinated by artists in Mexico City; additionally, in 2009 he founded the SOMA initiative, an organization dedicated to cultural exchange and arts education.

Gabriel Orozco (Jalapa, Veracruz, 1962) has gained international reputation as a renovator of conceptual art. He is one of the most representative members of the post-studio movement, which abandons the idea of a workshop, to work in direct contact with reality.

Orozco leaves behind all conventions regarding materials and tools,to take advantage of what he finds on the streets. He transforms forgotten or unusable objects into interpretations, criticisms or visions that have been defined as “poetry of the everyday”.

He lives and works between Tokyo, New York, Paris and Mexico City, where one of his most iconic pieces: the Mobile Matrix, is installed in the Vasconcelos Library. It consists of the bone structure of a gray whale, weighing almost 1,700 kilograms, intervened with drawings of circles and ellipses that represent the movement of waves and sound waves, as it floats mid space.

From 2009 to 2011 his work was the subject of an itinerant retrospective solo exhibition in galleries such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York; Kunstmuseum Basel in Basel; Centre Pompidou in Paris; and Tate Modern in London. Among his most remarkable solo exhibitions are those at the Palacio del Cristal del Retiro in Madrid (2005); the Serpentine Gallery in London (2004); the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (2000); the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1999), and the Museum of Modern Art in New York (1993).

José Clemente Orozco (Ciudad Guzmán, Jalisco 1883–Mexico City 1949) was one of the pillars of the muralist movement. He found encouragement in José Guadalupe Posada, whom he met as a child and whose influence was present in all his work.

In 1904 he lost a hand playing with gunpowder and some say that this had an impact on his personality, almost always withdrawn, with a tendency to melancholy. He was the most philosophical, complex and profound of “The Big Three”. His work differs from that of Siqueiros and Rivera, mainly because it does not privilege the triumphalism of war and revolutions, but rather emphasizes pain, loss, suffering, agony and death.

From 1927 to 1934 he settled in the United States. In New York he did a series of paintings that show a dehumanized and mechanistic character of the great metropolis. He was the first muralist to paint a fresco on freshly prepared plaster at the New School for Social Research in New York (1930).

Originally from Jalisco, he created what is considered his peak work in this state: the 57 murals of the Hospicio Cabañas building, where the Man of Fire (1939) is particularly noteworthy. His work transcended national boundaries and he is considered a universal painter, especially for his selection of topics, not only limited to nationalism, but also capturing the condition of humankind.

José Emilio Pacheco (Mexico City, 1939–2014) was a bibliophile and polymath who devoted his life to literature in different facets as poet, novelist, storyteller, essayist, translator, anthologist, journalist and cultural chronicler.

Among his key works are Battles in the Desert (1981), his most read book, considered a part of the literary baggage of several generations; and the anthology Sooner or Later (2009), which brings together his poetic work. On the other hand, his career was always associated with magazines and supplements such as Revista de la Universidad, México en la Cultura a supplement of newspaper Novedades, and La Cultura en México a supplement of Siempre!. Over the course of four decades he wrote the weekly “Inventario” —first in Excélsior and then in magazine Proceso—, his culture column was considered one of the most important and well read, in the country.

He received many honors and distinctions, most notably his appointment as Honorary Academic of the Mexican Academy of Language (2006); the Reina Sofía Ibero-American Poetry Award (2009), awarded by the National Heritage of Spain and the University of Salamanca, and the Miguel de Cervantes Prize (2009).

Pedro Reyes (Mexico City, 1972) studied architecture but considers himself a sculptor, although his works integrate elements of theater, psychology and activism. His work takes on a great variety of forms, from penetrable sculptures Capulas (2002-08), to puppet productions Baby Marx (2008), The Permanent Revolution (2014) and Manufacturing Mischief (2018). In 2008, Reyes initiated the ongoing Palas por Pistolas where 1,527 guns were collected in Mexico through a voluntary donation campaign to produce the same number of shovels to plant 1,527 trees. This led to Disarm (2012), where 6,700 destroyed weapons were transformed into a series of musical instruments. In 2011, Reyes initiated Sanatorium, a performative project that takes the form of a transient clinic that provides short unexpected treatments mixing art and psychology. Originally commissioned by the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, it has been adapted with each subsequent iteration.

In 2015, he received the U.S. State Department Medal for the Arts and the Ford Foundation Fellowship. In late 2016, he presented Doomocracy, an immersive theatre installation commissioned by Creative Time. In addition to his artistic practice, Pedro Reyes has curated numerous shows and often contributes to art and architectural publications. He lives and works in Mexico City.

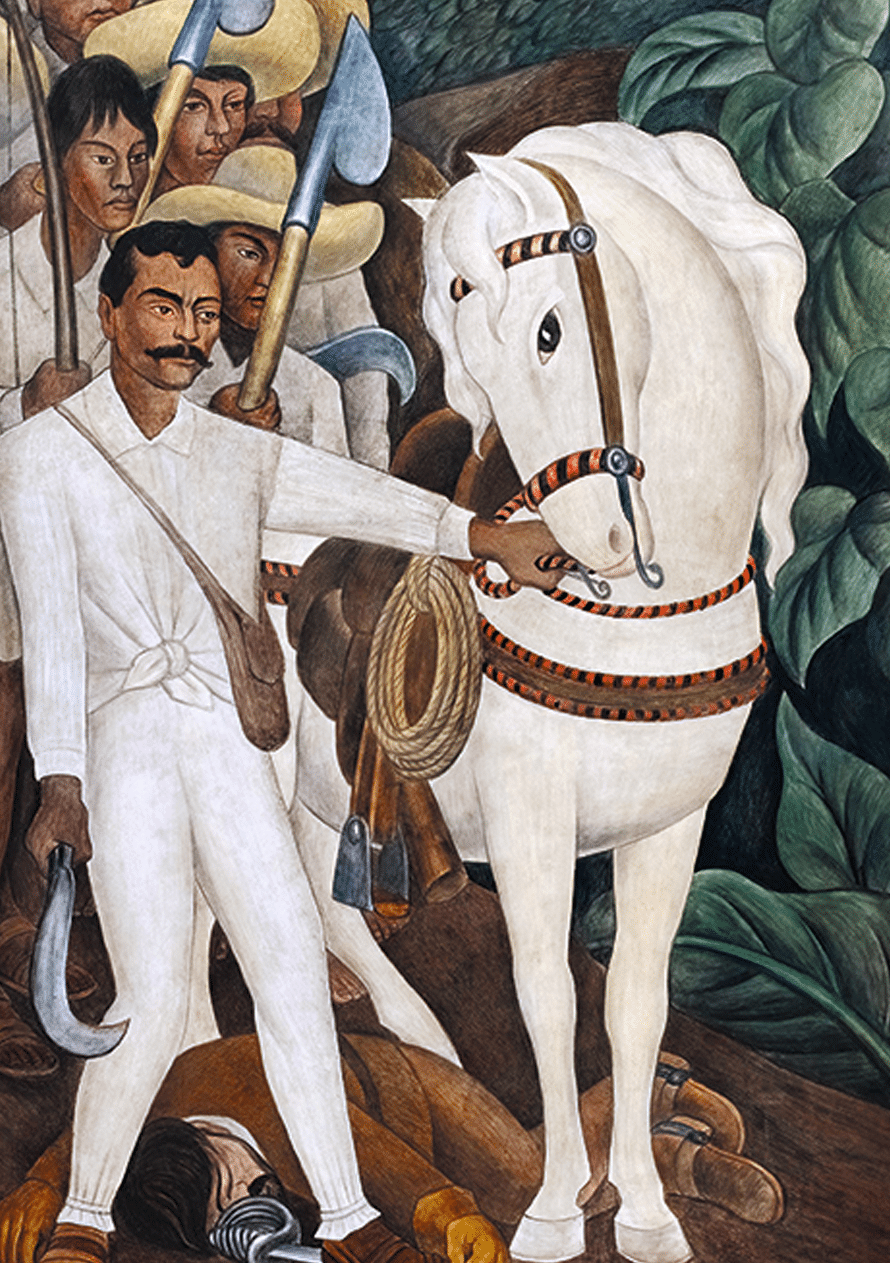

Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez, better known as Diego Rivera (Guanajuato, Guanajuato, 1886–Mexico City, 1957), is not only one of the most important artists of Mexico and the world —a key figure for the understanding of universal art— he is also an essential presence in the development of the history and politics of the 20th century.

In the mid-1930s, he already enjoyed worldwide recognition. He had painted his great murals in Mexico, after summoning Latin American artists to join an artistic movement that privileged the integration of society and the political and social importance of art. He was the second painter to present a solo exhibition at the newly opened Museum of Modern Art in New York, and caused great scandal regarding the destruction of his mural at the Rockefeller Center, in the same city, in 1933.

Rivera conquered the capitalist class of the most powerful country in the world and questioned it from the inside: he turned the walls of the lobby of its great center into an ode to communism. After the destruction, which was described as “cultural vandalism”, the work was resurrected on the walls of the Palace of Fine Arts under the name “Man, Controller of the Universe”. In 1954, the Palace of Fine Arts presented an exhibition that included more than 1,200 pieces, the fifty-year-old body of Diego’s creation.

Leon Trotsky defined him as “the great revolutionary artist” who tirelessly sought the construction of an authentic and egalitarian Mexico, and demonstrated that from a concrete idea, conceived in a third-world country, a cultural movement that reflects the identity of a country and modifies the perspective of art and of human kind can emerge.

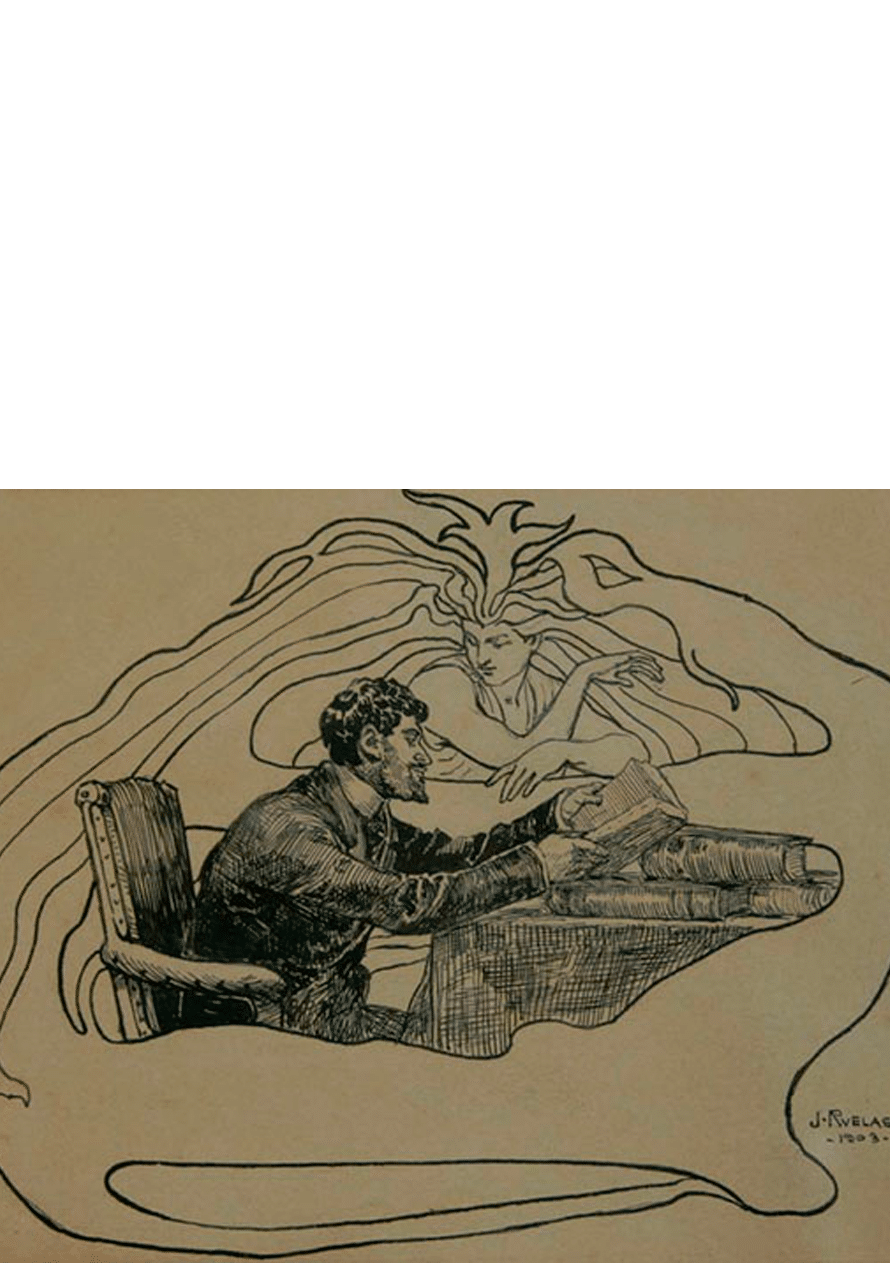

Known as “the damned illustrator”, Julio Ruelas (Zacatecas, 1870-1907) was one of the great exponents of Mexican Modernism. His proposal —fantastic, sadis- tic and grotesque— celebrated Decadentism and had a greater impact in Europe than in Mexico.

He was a student of the National School of Fine Arts and completed his studies at the University of Karlsruhe in Germany, where he met the creators of symbolism including Arnold Böcklin, Gustav Klimt and Edvard Munch.

Later he returned to Mexico where he became involved in the Revista Moderna project, a publication that emerged in 1898 and provided space for poets such as Amado Nervo, Rubén Darío and José Juan Tablada, in addition to publishing articles of scientific dissemination, social and cultural texts, current affairs, drawings and illustrations.

He always stood out for his originality and artistic independence. He died in Paris, France, in the style of a poéte maudit: among art, champagne and bohemia. His remains rest in a privileged spot in the Montparnasse Cemetery, from where “he can watch the girls go by”.

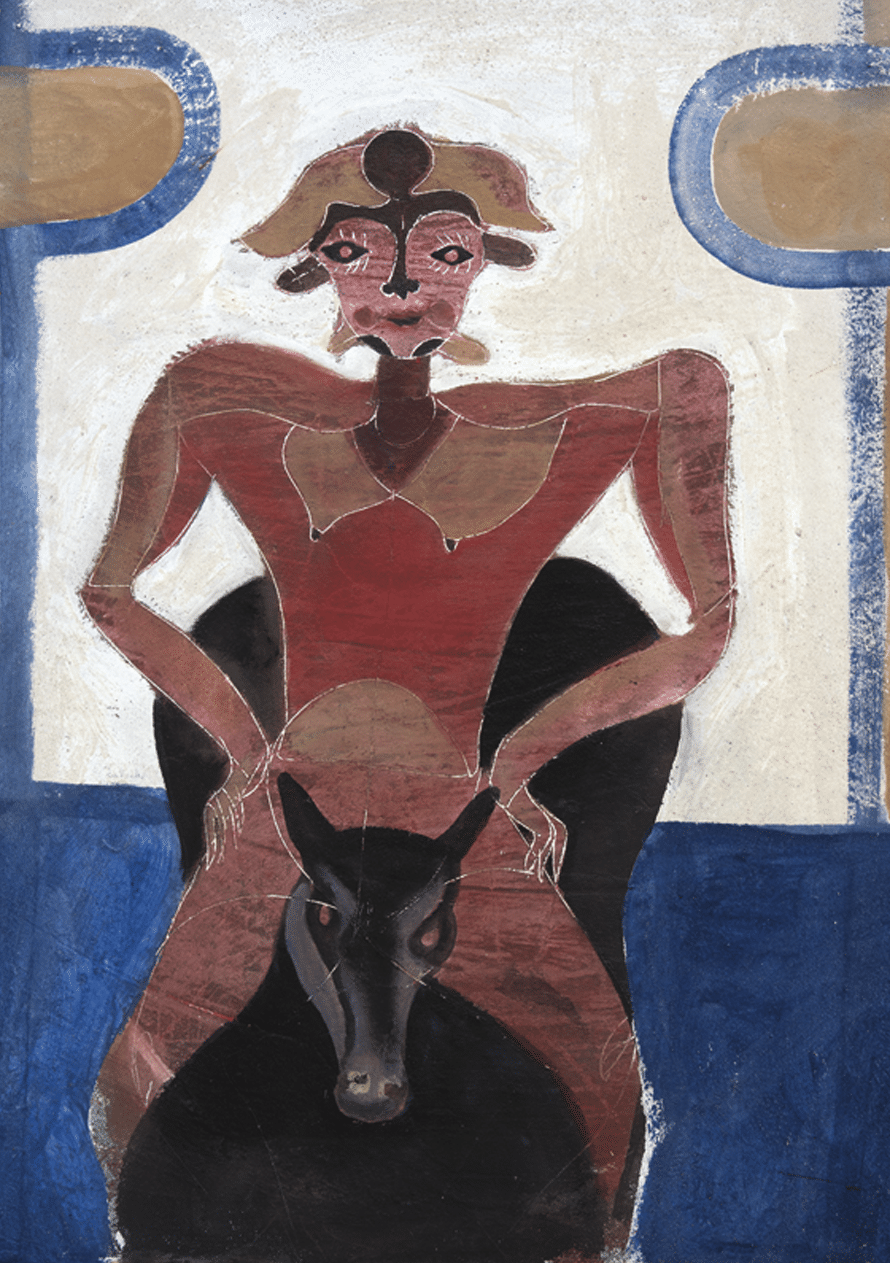

Originally from Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca, Rufino Tamayo (1899–1991) is one of the great Latin American muralists, known for his rebellious stance, as he kept his distance from some of the precepts of the nationalist movement in search of his own interpretation of Mexicanism.

“My sentiment is Mexican, my color is Mexican, my figures are Mexican —he stated— but my concept is a mixture [...]. I am Mexican, nourished by the tradition of my land, but at the same time I receive from the world and give to the world as much as I can: this is my creed as an international Mexican”.53 Instead of demonizing the influence of European trends, Tamayo embraced them and combined them with his profound knowledge of pre-Columbian art and his indigenous roots. Unlike Rivera, Siqueiros and Orozco, he chose free painting, without historicism or political proclaim, which gave his work a universal character.

His most iconic murals are Homenaje a la raza (1952) and México de hoy (1953). Over time he changed murals for canvases and easel; he was a forerunner of the mixograph technique and did 600 oil paintings, 400 portraits and 21 murals. The Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Internacional Rufino Tamayo in Mexico City is one of the most modern art centers in the world, which has promoted the work of hundreds of international artists.

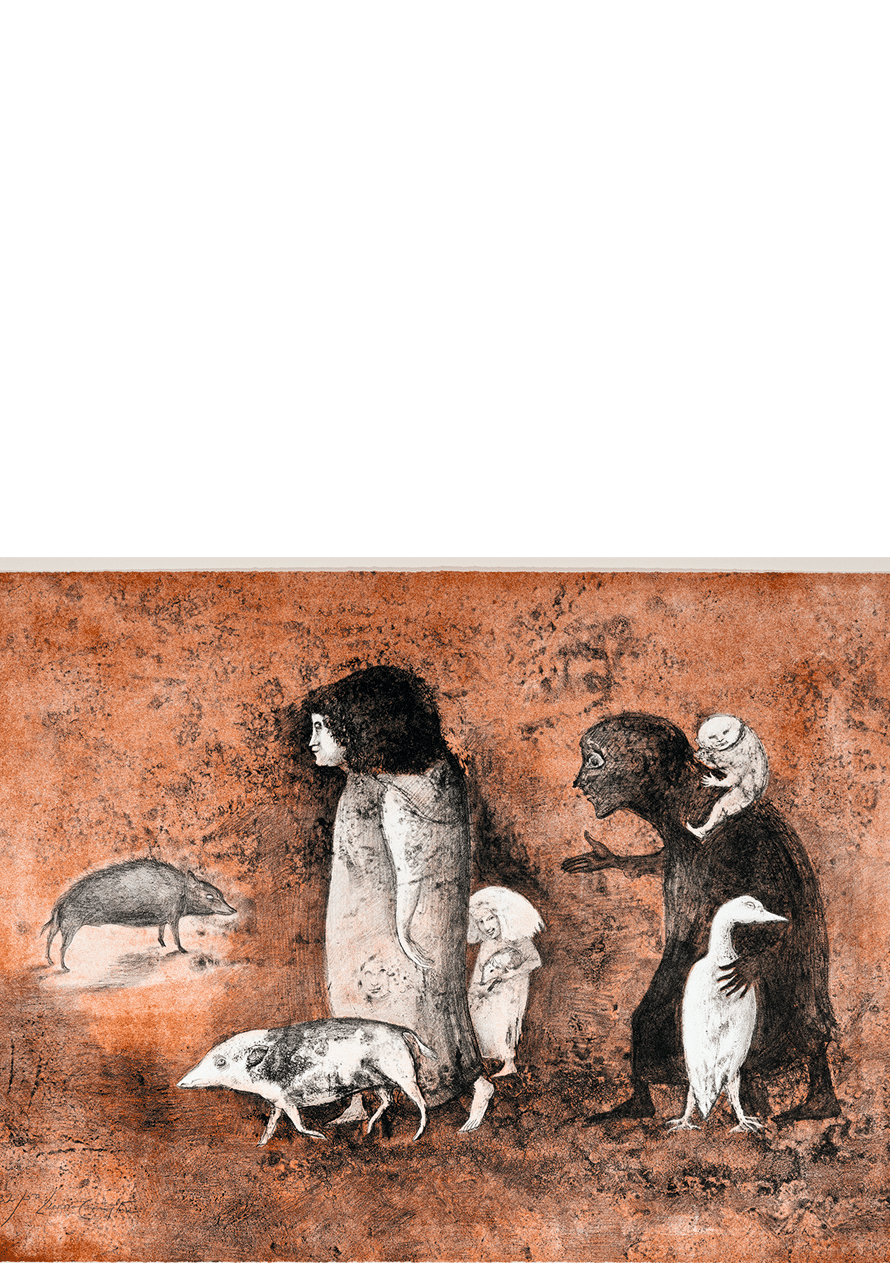

Art critic María Minera states that Francisco Toledo (Juchitán, Oaxaca, 1940-Oaxaca de Juárez, Oaxaca, 2019) is “the artist who opened the doors of the old universe of myths, and knew how to transfer them to the present […], a tireless creator […] of an ample body of work that owns —and owned since its inception— an ability for invention so unusual that without a doubt it is among the most interesting and irreplaceable research of Mexican art of all time”.

In 1959 he presented his first exhibition at Antonio Souza’s gallery; subsequently, he exhibited his work in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Belgium, Spain, France, Japan, Sweden, United States and other countries.

Endowed with unlimited creative vigor, he was not only an exceptional artist who cultivated every imaginable means of plastic, traditional and graphic arts —a master skilled in all techniques— he was also a true defender of heritage and memory, promoting and disseminating the culture and arts of his home state.

To this end he founded Ediciones Toledo, the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Oaxaca and the Centro Fotográfico Álvarez Bravo, among others. He also headed environmental projects to protect areas such as Monte Albán and the Papaloapan River, for which he received awards including the Federico Sescosse Award granted by UNESCO’s advisory body, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (2003).

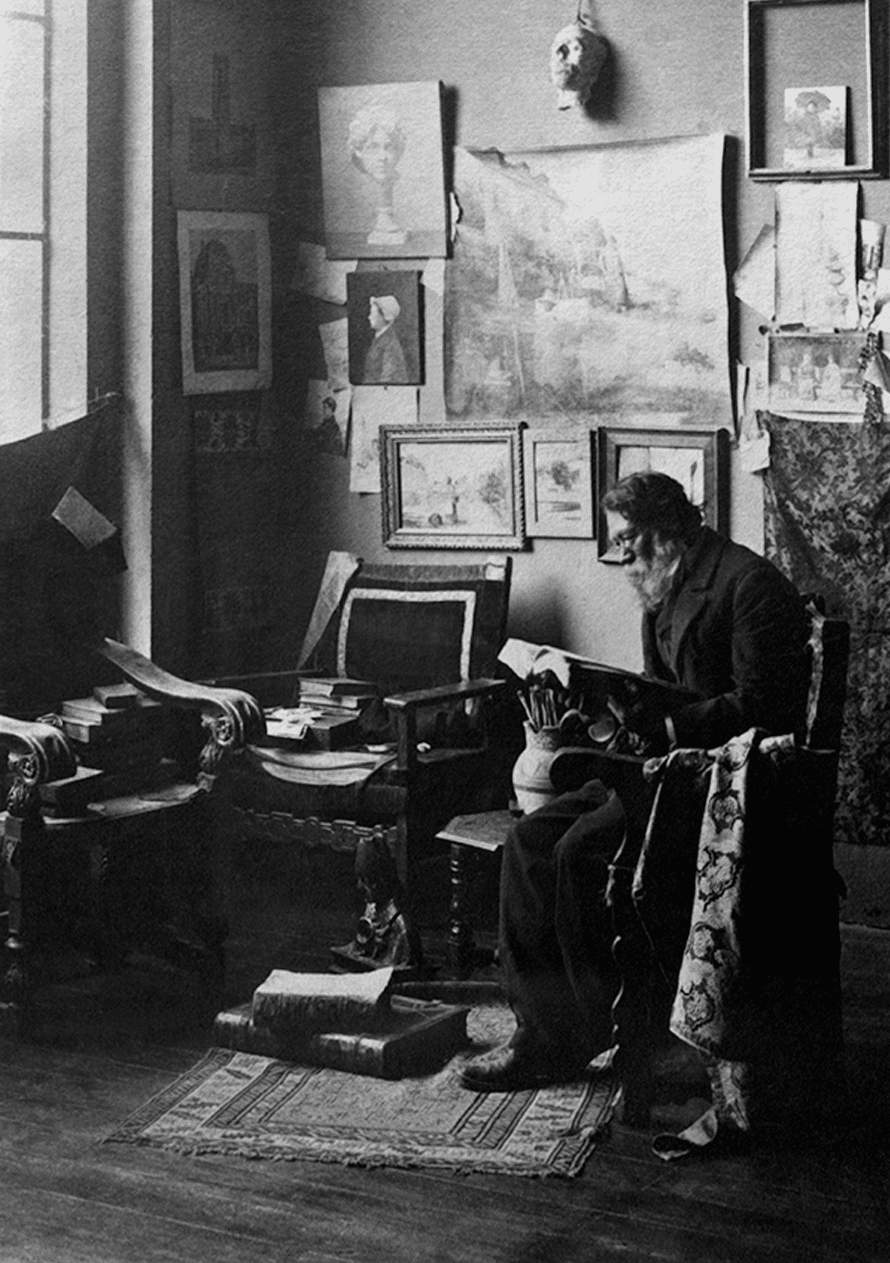

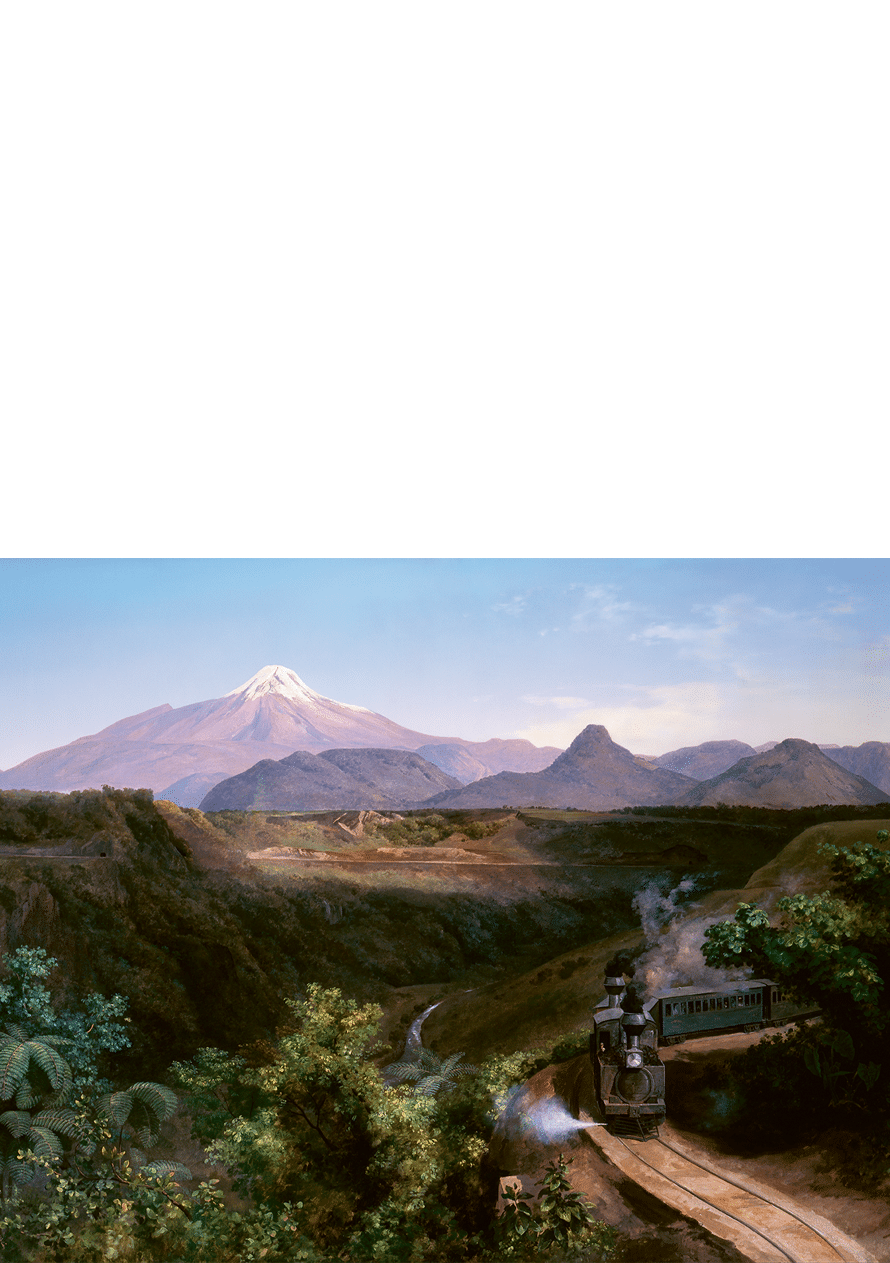

José María Velasco (1840–1912) was the greatest exponent of Mexican 19th century landscaping. Juan O’Gorman described him as one of the greatest painters in the world, whose work was not only to have painted landscapes “because there are thousands of painters who paint mountains, trees, ravines and landscapes, what Velasco did was to use the landscape to paint space. Space is the abstract theme of his painting […] with the color tone, he also painted time”.

He was born in Temascalcingo, State of Mexico, and studied night college at the School of Fine Arts of the Academy of San Carlos, and sold shawls during the day to make a living.

He was an innovator, while landscaping at that time was centered on the human figure, he focused his attention on nature and his vision was nourished by the studies he did in zoology, botany, geography and architecture.

In 1889 he was selected as head of the dele-gation that attended the Exposition Universelle of Paris, on the occasion of the centenary of the French Revolution. There he was appointed Knight of the National Order of the Legion of Honor. His work achieved universal recognition and put the name of Mexico on a par with Europe in the cultural field.