Atole is a beverage inherited from pre-Hispanic cultures made from maize dough and water, of different thicknesses and flavors.

The Nahuas were known for their light diet and were not accustomed to having breakfast. At midmorning, after a few hours of work, they drank a bowl of atolli —which means watery in Nahuatl— as their first nourishment; they drank it natural, sweetened with honey or seasoned with chili.

Atole is still an everyday drink for Mexicans and among its flavors and types are: strawberry, guava, pineapple, plum, capulin cherry, coconut, walnut, almond, St John’s wort, pinole, ash, white chocolate, with pieces of brown sugar, sour or xocoatole, cuatole (with honey and chili), chileatole, mezquiatole, xole (with cacao), nacuatole (with honey and pumpkin), broad bean and watónali (with fruits or herbs).

A burrito is technically a taco: a wrap made with a large flour tortilla with different types of fillings, traditionally prepared with meat, as well as beans, potatoes, cheese and other ingredients.

It is so popular in the United States that Tex-Mex food has claimed its invention for years, but burrito is an invention from the Mexican side of the border. Although there are several legends about its creation they all agree on one point: burritos were invented in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

The most widespread story tells that at the end of the 19th century —and even until the revolutionary era— there was a man named Juan Méndez, who sold food in rolled flour tortillas. He was so successful that every day he went back and forth from the Bella Vista neighborhood in Ciudad Juárez to El Paso, Texas, loading his merchandise onto a donkey —burro—, which would eventually inspire the name.

Sugar skulls and Mexican marigolds share the leading role in Mexican offerings during the celebration of the Day of the Dead. Tradition dictates that the name of our dead or of some living person for whom a long life is wished upon, must be written on the front of the skull.

This sweet is the Mexican version of alfeñique, an Arab technique inherited by the Spaniards during the Muslim conquest that, once they became conquerors, they brought to the New World along with sugarcane. It was used to replace the skulls that in pre-Columbian times were placed in tzompantlis to honor the gods.

The image of the sugar skulls, with their colorful decoration of shiny papers and icing, has become a symbol of Mexican tradition throughout the world.

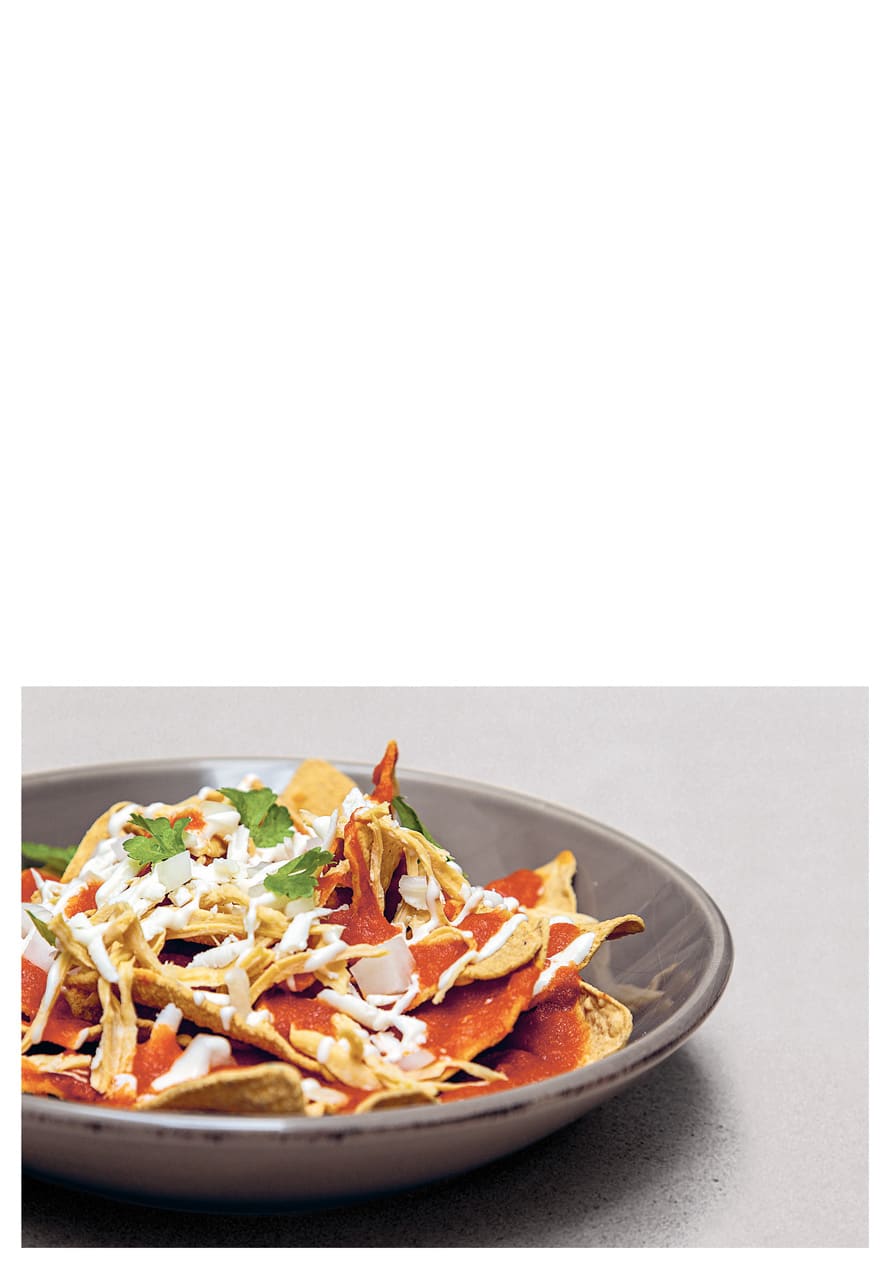

This dish is made with tortilla chips, fried or toasted, bathed in green or red chili sauce. Its origin is a legacy of the culinary richness of the inhabitants of pre-Hispanic Mexico, who took advantage of all the food, including hardened tortillas left over from the previous day, which they softened by soaking them in chili sauce.

According to philologist and historian Ángel María Garibay, the word chilaquiles comes from the Nahuatl chilaquilli, a word composed of chilli (chili) and aquilli, which means “to be within something”.

Nowadays they have become an ideal breakfast food. Crunchy or soaked in the sauce, they are served with shredded chicken, chorizo or egg, sprinkled with cheese and a dollop of cream.

The traditional chiles en nogada can be enjoyed in September, the month of national festivities in Mexico. This dish, originally from Puebla, includes more than twenty ingredients.

There are two legends regarding their origin: the first attributes their invention to the nuns of the Santa Mónica Convent, who created a recipe to celebrate the birthday of Iturbide and the triumph of his army in 1821; using seasonal ingredients such as poblano chili, pomegranate and walnut to portray the colors of the flag of the Three Guarantees Army.

The second legend was divulged by writer Artemio del Valle Arizpe, who in his book Sala de tapices stated that the Three Guarantees Army had three soldiers whose brides lived in Puebla; after their heroic deed the young women were anxious to celebrate the return of their lovers, so they decided to welcome them with a big banquet. Each one chose an ingredient that represented a color of the flag and, with the blessing of St. Paschal Baylon, they created chiles en nogada.

Within the vast variety in Mexican cuisine, Yucatán’s gastronomy is one of the richest, as the result of the mixture of Mayan ingredients with flavors brought from Europe, the Caribbean and the Middle East, and whose most famous dish is cochinita pibil.

Pibil comes from the Mayan and means “buried”. This dish is prepared with pork meat marinated in annatto and wrapped in banana leaves; it is cooked slowly, for several hours, on hot stones inside a hole in the ground covered by leaves. It is served in tacos or tortas, garnished with red onion infused in sour orange and habanero chili.

The origin of cochinita pibil is pre-Hispanic; it is similar to a dish made with venison, pheasant or wild boar, which was typical of hanal pixán or “food of the souls”, a tradition of the Maya people held to celebrate the dead.

Enchiladas are a dish made from soft corn tortillas, lightly fried, rolled or folded in half and covered with sauce; they are usually stuffed with meat, chicken or cheese.

They are one of the most popular specialties of Mexico’s cuisine. There are different versions of enchiladas for each region of the country, which vary depending of the sauce and preparation, although the most popular ones are green, red, and mole enchiladas, garnished with onion rings, cream and grated cheese.

In Mexico City, Swiss enchiladas —green sauce, stuffed with chicken, covered in cheese and baked in the oven— are especially popular. In El Bajío region, the typical enchiladas are the mineras, with guajillo chili and a touch of oregano and cumin; or the ilustradas, the sauce of which is prepared with ancho chili, coriander seeds, cloves and ground cinnamon, among other ingredients.

In Oaxaca enchiladas are prepared either with black mole or Totolapam style, also called enchiladas de coloradito; while in the Huasteca the specialty are the potosinas, where tortilla dough is prepared with chili first. The recipe has so many variations that one could take a gastronomic tour through all the states of the country and find different types of enchiladas in each one.

Caesar salad is a must-have dish in the repertoire of hotel menus and in the most important international cuisine restaurants. It is made with lettuce and crisped bread, seasoned with a mixture of garlic, olive oil, anchovies, hard-boiled egg and Parmesan cheese. Although there are several stories about its origin, it is officially known that it was created in Tijuana, Baja California, in 1924, by brothers César and Álex Cardini.

According to the most widespread version, on July 4, 1924, César Cardini was tending a large number of customers in the Hotel Caesar’s restaurant when the kitchen supplies ran out, forcing him to improvise with what little he found in the pantry. Thus, he created a simple but delicious salad diners fell in love with.

Another story tells that the mother of the Cardini brothers already prepared a similar salad with cheese and bread, known in her hometown in Italy, near Lake Maggiore.

On the other hand, the National Chamber of the Restaurant Industry and Seasoned Foods (Canirac) assures that it derived from an Austrian recipe brought to Mexico by Libio Santini, who was assistant chef at the Caesar’s restaurant.

Beyond the controversy of its origin, Caesar salad traveled from Tijuana to the world and although its recipe has been modified with the passage of time to include chicken slices, bacon or other ingredients, its essence remains intact.

According to Diana Kennedy, who recovered the recipe prepared by Álex Cardini, the dish was originally prepared with slices of bread baked in the oven until crisp and smeared with a mixture of crushed garlic with anchovies and olive oil; the whole romaine lettuce leaves are mixed with egg yolk run under hot water, lime juice, Worcester sauce, grated parmesan cheese, salt and pepper, until well combined.

Made from maize, esquiate is a multipurpose food: it can be considered a drink or a soup that eases hunger and thirst, while nourishing. The Rarámuris of the Tarahumara mountain range take it daily, since it provides them with enough energy to travel dozens of kilometers without stopping, day and night.

The Tarahumara women thresh the maize —mainly the white crystalline grain, yellow crystalline grain, blue or Chihuahua popping races— and heat it with stream sand in a clay pot called esquitera, until the maize bursts into the shape of popcorn, which they call esquite. From esquite ground on a quern, they extract pinole —roasted ground maize— that they consume dry; when water is added during the grinding they obtain esquiate that can be taken alone, as a drink, or accompanied with flowers or pigweed as a soup.

Thanks to Tarahumara runners’ fame as the best in the world, esquiate has attracted attention, increasing the consumption of pinole as a superfood among the sports community.

Cooking is more than the food of the earth. It is an act of creativity, a fact loaded with symbolism of the highest cultural significance.23

Conservatory of Mexican Gastronomic Culture

The set of ingredients, techniques and recipes that make up Mexican cuisine is an ancestral, popular and current legacy that guards our roots and history and determines our identity. This heritage has its origins in the pre-Hispanic period —with the triad made up by maize, beans and chili— and was turned on its head with the conquest, when Old World ingredients and techniques were incorporated, enriching our cuisine without altering its character or authenticity.

The culinary culture is part of a complex cultural model that includes everything from agrarian activities to ritual practices, as well as customs and forms of community behavior to reach the stoves of each home, where techniques, preparation and respect for food are preserved.

In recognition of this richness, in 2010 Mexican traditional cuisine was declared Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO, taking as reference the Michoacán paradigm. This was achieved thanks to the work of a group of cooks, researchers, promoters and historians through the Conservatory of Mexican Gastronomic Culture.

Standing out in this project is the work of cook Juana Bravo Lázaro and writer, journalist and diplomat, Gloria López Morales, who stated that the inscription “is not an exercise of collective pride”,24 but a fundamental step that will allow the rescue, safeguard and promotion of our gastronomy.

This example constitutes a model that should be copied in different centers of culinary irradiation in our country, such as Oaxaca, Yucatán, Puebla, Guerrero and Veracruz, in order to protect the vast culinary heritage of each of these regions.

Guacamole is a sauce prepared with ripe, crushed avocados that can be served alone or with a mixture of green chili, tomato, onion and coriander —sometimes a few drops of lime juice are added to stop the fruit’s oxidation. It is a classic in Mexican cuisine that is consumed in almost the entire world.

Its origin dates back to pre-Hispanic times and its name comes from the Nahuatl ahuacamolli, which combines the words ahuacatl (avocado or testicles) and molli (sauce).

In Mexico it is served as a side dish or sauce in any type of taco or quesadilla; it is also eaten as a snack, accompanied with tortilla chips. There are regional variants where aromatic herbs are added to the mixture; fruits like peach, grape or pomegranate, or insects like stink bugs or grasshoppers.

This cocktail, made of tequila, holds the eighth place among the best selling cocktails in the world. It was created by Daniel Negrete in 1936, when he worked at the Garci Crespo Hotel in Tehuacán, Puebla.

At the elegant bar of the hotel, the bartender met Margarita Orozco, a recurring guest who had the peculiar habit of accompanying her drinks with pinches of salt. One night, inspired by one of their long conversations, Daniel placed ice in a mixer, squeezed several limes, added Triple Sec, took a champagne glass and frosted its edges in a salt ring for Margarita's comfort, who no longer had to bother constantly reaching for the salt shaker.

This mestizo drink was born thanks to the arrival of the still and distillation system in New Spain. At present, a distinction is usually made between mezcal and tequila, but in reality “mezcal” refers to all spirits that are obtained from the various types of agave, including tequila, the fame of which has overshadowed its congeners.

The generic name comes from the Nahuatl mexcalli, which means “cooked maguey ribs”. However, each mezcal is named according to its native region: bacanora, in Sonora; xtabentun, in Yucatán; sotol, in Chihuahua; charanda, in Michoacán; tequila, in Jalisco; or comiteco, in Chiapas —to name a few. Mezcal, par excellence, is produced in Oaxaca, where it is still respected as a ritual drink in the Zapotec indigenous culture.

Under this name that comes from the Nahuatl molli, meaning “salsa” or “stew”, an infinite number of complex dishes of pre-Hispanic origin come together, representing an important part of the identity of several regions of the country.

Originally, moles were prepared for the gods, based on a series of ingredients crushed and mixed in a metate. Historian Cristina Barros tells that Pochtecas, upon arriving at their home after a journey, offered “chicken heads in caxetes with their molli” to Xiuhtecuhtli, god of fire.33 Currently, there are moles for every occasion, although in many traditions their consumption is reserved for celebrations or rituals.

In Oaxaca, they preserve the legacy of the seven moles: black, coloradito, red, yellow, green, chichilo and manchamanteles [tablecloth stainer], present at the festivals of each region; while Puebla is the cradle of the famous poblano mole, a variation of the pre-Hispanic mole, legacy of the nuns of the convent of Santa Rosa that includes over 22 ingredients.

There are also the mole de panza, mole de olla or the michmole, which in their preparation are more similar to a substantial soup. The Diccionario enciclopédico de la gastronomía mexicana has records of over 90 varieties of this dish.

Upon his arrival in the New World, Cortés was adorned with garland necklaces woven with curious edible and delicious flowers that the natives called mumúchitl. Later he learned that in reality those small buds were not born so, but were grains of maize burst with heat, which were eaten at festivities in honor of Xipe Totec, god of regeneration, maize and war.

Sahagún described mumúchitl as “a very white flower in each grain”. The indigenous people obtained it by placing the cobs on the fire, skewed on a stick, or separating the grains and heating them in clay pots with sand.

Pico de gallo is a hybrid between sauce and salad traditionally prepared with tomato, onion, jalapeño chili pepper and coriander, all fresh and diced; some preparation methods include a few drops of lime juice.

This seasoning is a classic of Mexican cuisine that is used to accompany any dish, but especially molletes, nachos, quesadillas and tacos, or simply to enjoy with tortilla chips. Due to its uses and ingredients, and for bearing the traditional colors of the national flag, it is considered the queen of sauces. It is also known as raw sauce, chopped sauce, Mexican sauce or flag sauce.

There is no confirmed theory about the origin of its name. The Diccionario enciclopédico de la gastronomía mexicana states that it is named this way because its ingredients are finely chopped and resemble the food that birds feed on, although many people are inclined to believe that it is called this way because you have to be tough to eat it, since in Spanish gallo can mean both rooster and tough.

Pozole is a broth prepared with cacahuazintle maize, meat and chili, garnished with chopped radish, onion and lettuce. It is the quintessential dish of national celebrations, although since its pre-Hispanic origin it has been linked to great festivities.

According to Friar Bernardino de Sahagún’s descrip-tion in General History of the Things of New Spain, during the rites in honor of god Xipe Tótec —the skinned lord, god of regeneration, maize and earth— Emperor Moctezuma was served a plate with the thigh of a sacrificed man, boiled with maize. This ritual dish was called tlacatlaolli and is the precursor of pozole, name derived from the Nahuatl pozolli, which means “boiled” or “frothy”.

Nowadays it is traditionally prepared with pork meat, although there are also states in the country where they prefer it with chicken and even with sardine or shrimp.

There is white pozole, which is accompanied by tomato or tomato-based sauces: green or red, depending on its ingredients. Both can be served with oregano and lime juice.

This mestizo antojito consists of a tortilla —made of maize dough or wheat flour— folded in half in the shape of a half-moon, filled with melted cheese or any type of stew.

In some regions of the country, especially in the north, south and southeast, quesadillas are filled exclusively with cheese, while in Mexico City the ones made on a hotplate prepared with countless fillings are famous, including mincemeat, potatoes, sliced chili peppers, mushrooms, shredded chicken, maize smut or pumpkin flower, with or without cheese. They can be served alone or open to add sliced lettuce, chopped onion, grated cheese, cream and chili sauce. In other places, such as Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, shrimp quesadillas are prepared fried, accompanied with pickled chilies.

This difference in their fillings has caused a controversy regarding their name. According to the Diccionario enciclopédico de la gastronomía mexicana, they are named after their main and original filling, which is cheese, but popular custom accepts as quesadillas the latter even if they are prepared without this ingredient.

Aztec soup is a traditional dish originally from Tlaxcala, a state whose name means “Place where tortillas abound” or “Land of maize”. It is popularly known as tortilla soup and it is the quintessential soup in Mexico.

It is made from fried maize tortilla strips, dipped in chicken broth and epazote, seasoned with tomatoes, garlic, onions and dried chili —either pasilla or ancho variety. To this base one can add other ingredients such as panela or ranchero cheese, avocado, shredded chicken, cream and pieces of pork rind, among others, which can be seasoned with lime juice.

Tacos are the top culinary ambassadors of Mexico in the world. They are prepared with maize or wheat flour tortilla, folded or rolled, stuffed with any type of stew or meat.

Their origin was a diversion of the use of the tortilla, which was originally used as a spoon or edible plate. The natives called it tlatoalli, which means “tortilla with filling”.

It is the most eaten antojito in our country, with a perennial presence at home tables, restaurants, diners, markets and street stalls. Their name almost always refers to the way they are prepared or their specialty. Among the best known are the dorados —fried in oil— soft ones and steamed tacos; there are even tacos with no filling, which are just a simple folded or rolled tortilla, served naturally or fried, alone or with chili sauce.

Tacos al pastor are also known as trompo tacos, they are filled with pork meat, marinated in a sauce of dried chilies and annatto, which is skewered on a sword, resembling the shape of a spinning top crowned with a pineapple, which the taquero turns manually while grilling. They are served with chopped onion and coriander, lime juice and chili sauce.

These famous tacos, catalogued as the best dish in the world by Taste Atlas website, appeared in the 1920s when a group of Lebanese people merged the shawarma technique —prepared with marinated lamb meat and cooked on a skewer— with local ingredients.

Of the great variety of dishes made with nixtamal dough, the most important are, undoubtedly, tortillas and tamales —originally called tamalli, which means “wrapped” in Nahuatl.

The dough, mixed with a filling or simply chili sauce with meat and vegetables or beans, is carefully wrapped in maize or banana leaves, and then left to steam.

In ancient Mexico, tortillas were the everyday food, while tamales were kept for large festive banquets. Their origin is linked to the domestication of maize. Evidence has been found, at the archaeological site of Teotihuacán, that suggests their use between the years 250 B. C. and

750 A. D.

Nowadays, tamales are no longer a dish for special occasions and have become a part of daily life of Mexicans, especially in Mexico City, where tamale in a bread roll is essential nourishment. Tamales also continue to be protagonists of celebrations such as the Day of the Dead, La Candelaria and Christmas in northern Mexico.

There are over 500 types of tamales: from chipilín to casserole tamale, chanchamitos, piltamales, vaporcitos and zacahuiles, among many others.

Tequila is the best-known agave distillate in the world. It is obtained exclusively from the blue agave tequilana variety —tequilana Weber— that grows mainly in the town of Tequila, Jalisco.

It has been consumed since colonial times and at the end of the 19th century it began to be exported under the name vino mezcal de Tequila. Later, by distilling this mezcal for a second time, it began to be marketed as we currently know it.

Revolutionary times gave tequila a final boost. Both national rebirth and film, one of its main promoters, took to the farthest corners of the world the image of happy and resolute Mexican riders, who both cured their sorrows and celebrated their joys by drinking tequila.

This spirit is popularly taken in a shot glass known as tequilero or caballito. It can be drunk straight or partnered with sangrita, and it is used in cocktails such as paloma, margarita, charro negro, vampiro and cucaracha.

The agave landscape of Tequila, Jalisco, from which this iconic drink derives its designation of origin, has been declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, in recognition of its beauty and cultural importance.

The transformation of maize into tortilla has been, for centuries, a main element in the diet of Mexicans. It can be described as a thin circle made of maize dough, traditionally cooked on a hotplate. Its invention is attributed to the Olmec culture, the first people that cultivated fully domesticated maize on the southern Gulf of Mexico coast.

In the General History of the Things of New Spain, Friar Bernardino de Sahagún dedicated several pages to describe tortillas: “The tortillas the lords ate every day are called totonqui tlaxcalli tlacuelpacholli, meaning ‘folded white and hot tortillas’ […]; they also ate other tortillas every day called veitlaxcalli, meaning ‘large tortillas’, these are very thin and wide and very smooth”, among many others.55

Tortillas are eaten hot and are used as a plate, cutlery and wrap. Whether made by hand, using homemade tortilla makers or made in industrialized machines, they are the raw material for preparing tacos, quesadillas, enchiladas, enmoladas, entomatadas, flautas, tostadas, tortilla chips, chilaquiles, soups and an endless number of dishes.

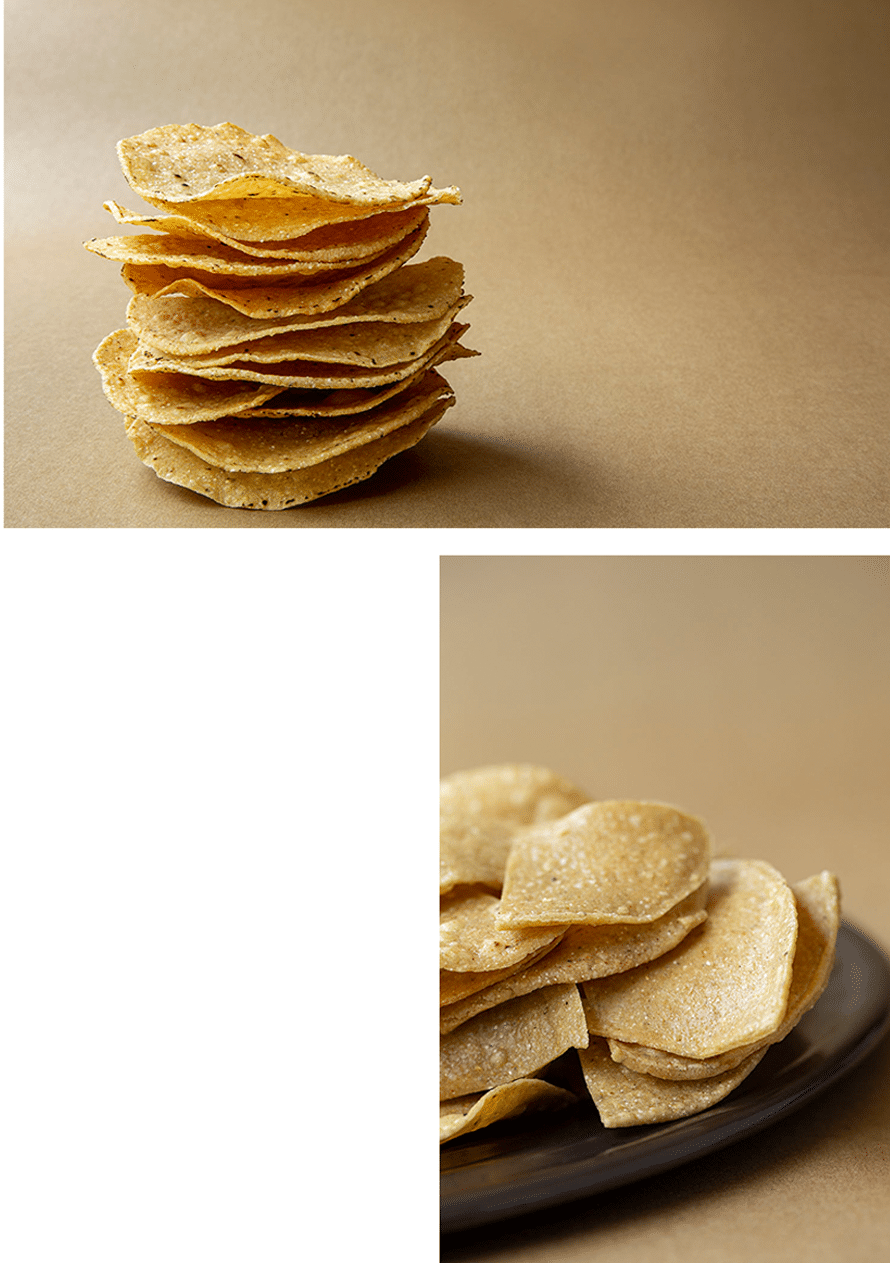

These antojitos made from crunchy maize tortillas can be prepared in the oven, sun-dried, toasted on a hotplate or fried in oil. They are usually eaten with food on top, and their preparation varies from one state to another: in Oaxaca, chileajo tostadas with bean spread are popular; in Mexico City they are topped with cow trotters or shredded chicken; in Hidalgo and Tlaxcala you can try cured tostadas dipped in pulque and dried on a hotplate, although they can also be enjoyed on their own, dipped in sauce or tasty guacamole.

Another use for tortillas are the typical totopos, which are crunchy maize tortilla chips, cut in a triangular shape, used as the base of chilaquiles or as a snack. It is known that from very old times people ate leftover toasted tortillas, known as totopochtli, which in Nahuatl means “toasted”. In Oaxaca there is a very traditional totopo made in special clay pots called “comixcales”.

Tortilla chips are so popular that even today there are commercial snack brands, inspired by their shape and flavor, which are sold all over the world. They are ideal for decorating typical dishes and for eating with guacamole, refried beans, chili sauce or any type of dip.