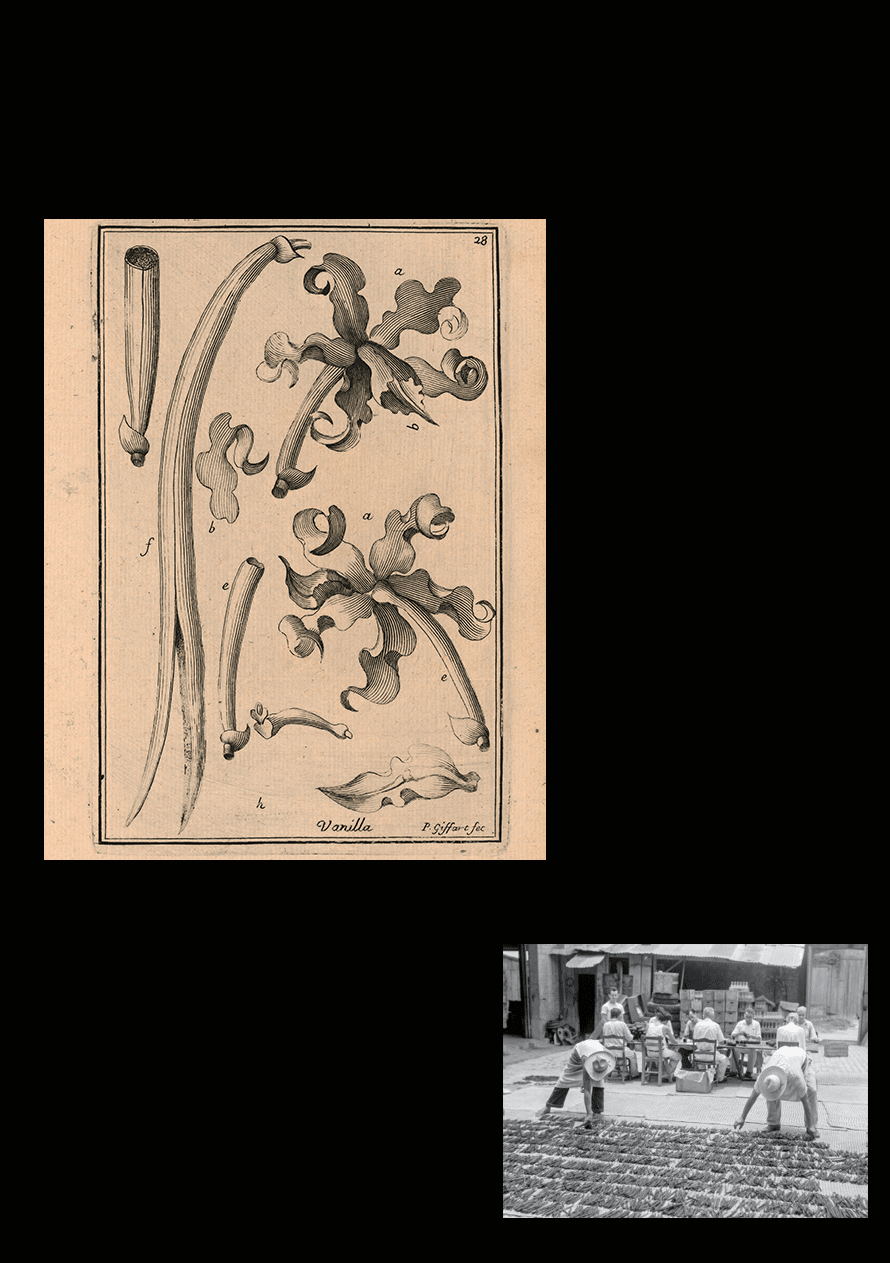

The pod of this orchid was much appreciated by the Aztecs, who mixed it with cacáotl to give it fragrance and flavor; they consumed it dissolved in water as nourishment for the brain or as a remedy against venom and bites of poisonous animals. Its name in Nahuatl is tlilxóchitl, which means “black flower”.

After the conquest it was taken to Spain to make perfumes and add scent to chocolate. In his Universal Dictionary of Natural History, Valmont de Bomare stated that among its benefits, “vanilla fortifies the stomach, helps digestion, dispels flatulence, promotes periods and urination, facilitates birth, and the English specifically appreciate it for banishing the effects of melancholy”.56

In France it was not only used in perfumery and medicine, but also for baking. Kitchens all over the world have been flooded by the enveloping aroma of vanilla, considered one of the most used flavorings on the planet.

The legend of its origin is pre-Hispanic from Totonac mythology, and tells how Tzacopontziza —“bright star of dawn”— daughter of king Tenitztli the third, had taken chastity vows, consecrated by her father to the service of Tonacayohua, the goddess of sowing and food, but fell madly in love with prince Zkotan Oxga —“young deer”. The young lovers fled, a sacrilegious act that had to be punished with death, so they were persecuted, imprisoned and their throats were slit. Their hearts in love were offered to Tonacayohua, and an orchid of exquisite aroma grew on the site of the sacrifice.

Jorge Vallejo is considered one of the most important figures in contemporary Mexican cuisine. He discovered his calling as a teenager, when his mother forced him to work in a family friend’s restaurant as a punishment for being expelled from high school in Mexico City.

He washed dishes, cleaned tables, chopped ingredients and discovered a path that took him to the Centro Culinario Ambrosía and from there to several kitchens on cruise ships and countries such as Spain and Denmark. He returned to Mexico and joined the Pujol restaurant team, next to Enrique Olvera. In 2012 he opened Quintonil restaurant in Mexico City, together with Alejandra Flores, his wife and partner.

His work is defined by a commitment to the authenticity of flavors, which has led him to reinterpret traditional recipes in modern dishes that preserve their essence. From the name of his restaurant he pays homage to his origins: quintonil is a Nahuatl word that refers to amaranth and means “wild grass with tender and edible shoots”.

His work and creativity in Quintonil have been recognized with a nomination to the Travel + Leisure Mexico Gourmet Awards 2012, in the category of Best New Restaurant, as well as being one of the favorites in The World’s 50 Best Restaurants list, published by the English magazine Restaurant.

Among the culinary techniques that have been practiced in Mexico since pre-Columbian times, one of the most important is steam cooking, a procedure that preserves nutritional values of food and that was used, mainly, in the preparation of tamales.

The tecontamalli was invented for this purpose; the clay pot’s bottom is covered with water over which a grid of canes, dried leaves and other herbs are placed. On this vegetable bed tamales were placed over low heat. This pre-Hispanic instrument was also used to vaporize meat, maize and chayote squash.

Researcher Heriberto García Rivas states that French chef Marie- Antonin Carême, creator of the first industrial steamer for the kitchen in the 19th century, accepted that his invention would not have been possible without the inspiration of the pre-Hispanic version.

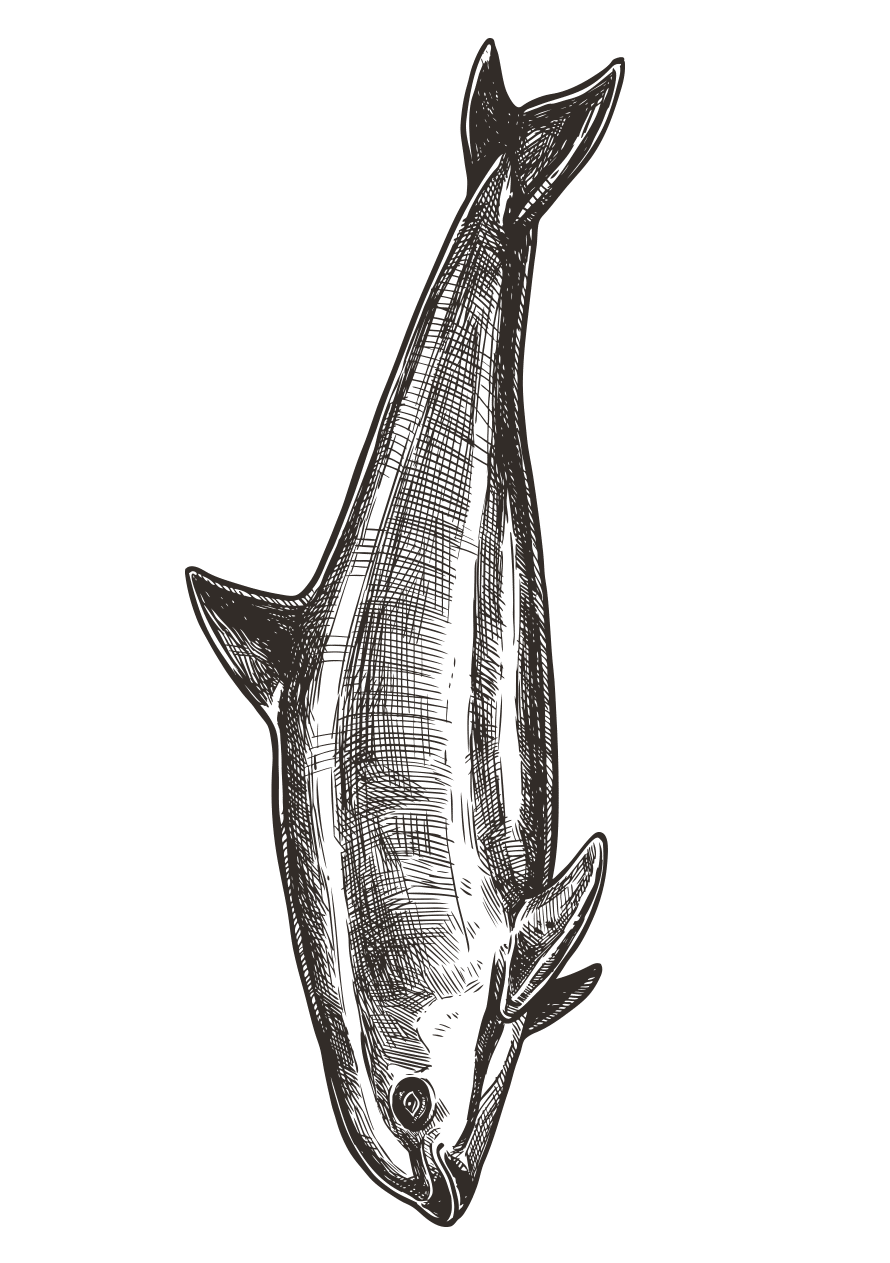

The vaquita is considered the smallest cetacean in the world. Although it is estimated that this species has existed for three million years, it was discovered by chance in 1950 by the renowned biologist Kenneth Norris, who toured the coastal dunes of the Sea of Cortez in search of a species of lizards and ran into the curious vaquita [small cow], named after its peculiar coloration with long gray spots and black patches around its eyes and snout.

Also known as “the ocean panda”, the vaquita is sadly famous for being the most endangered mammal species. Its misfortune lies in the fact that it coexists with the totoaba, a very coveted fish for oriental cooking, so the vaquita dies when trapped among fishing nets.

Isabel Vargas Lizano (1919–2012) was born in Costa Rica, but she was Mexican because she decided to be one, “us Mexicans are born where we feel like it”, she used to say. So she also decided to call herself Chavela —“Chavela, with a ‘v’, to piss everyone off”— and become the voice that gave life and legend to Mexican popular music, growing out of all preconceived roles.

It is said that she arrived in Mexico at age 17 and before singing she was a cook, waitress and chauffeur for high society families. It took her over two decades to make a living from singing, despite having the support of José Alfredo Jiménez —accomplice of endless parties.

With her manly and raspy voice due to drink-ing too much alcohol, her eternal cigar, always with her pants on and wearing her poncho, she managed to record her first album in 1961. From there on she recorded over 80 albums and dedicated herself to singing, not only in bars, but also in concerts, television programs and films such as Kika by Pedro Almodóvar; Frida by Julie Taymor, and Babel by Alejandro González Iñárritu, among others. She wanted to sing herself to death, and her friends say that she had set her mind to die, literally, on stage. She did not succeed, but for sure she continues singing in some limbo and will continue to do so just because she decided to.

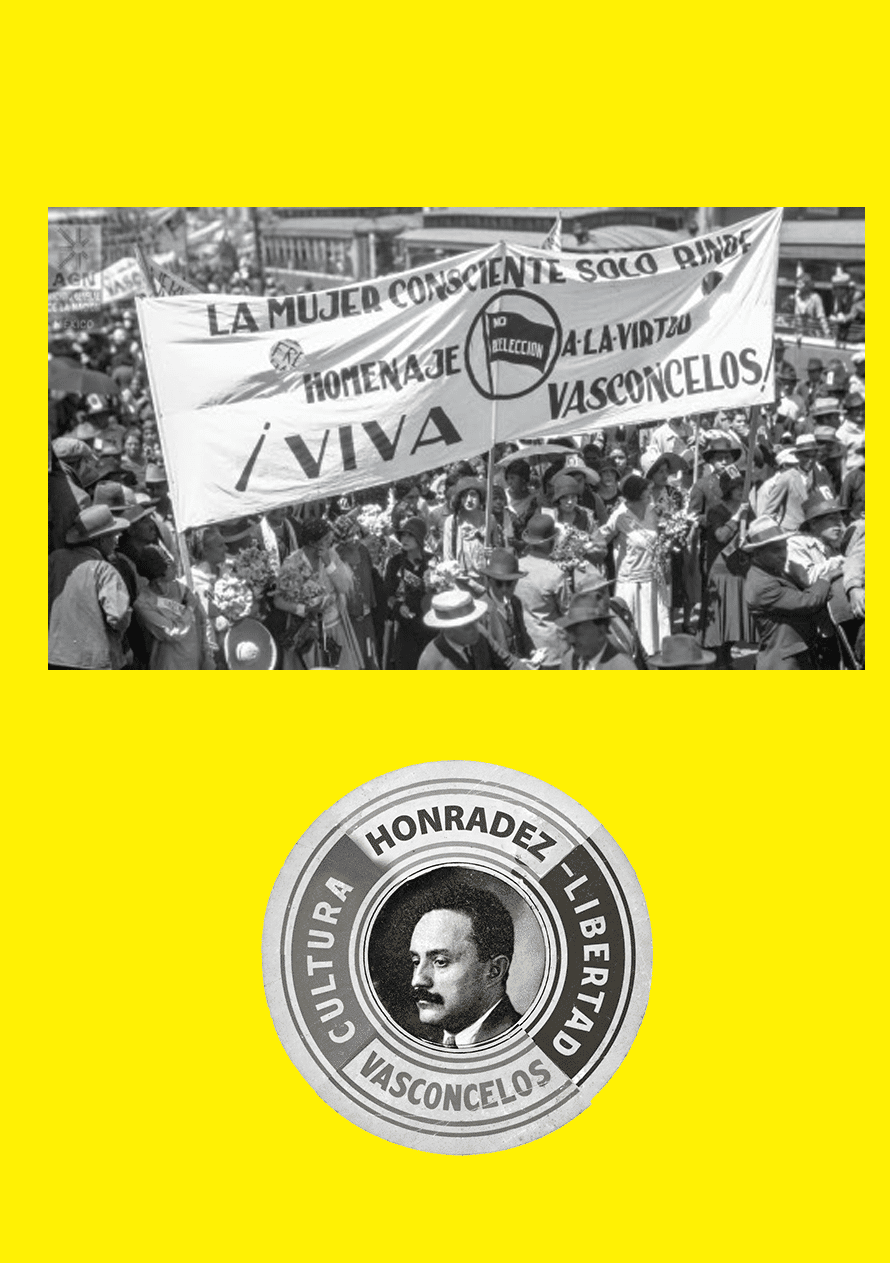

Originally from Oaxaca, José Vasconcelos (1882–1959) was called none other than “Teacher of America’s Youth”. Interested in political life —permanently critical, opposed to the government— he stood out as an academic and philosopher, and left an extensive work recognized with the highest literary value.

His creation includes collected letters, criticism and fiction on a variety of topics, including ethics, aesthetics and metaphysics, highlighting the autobiographical series that begins with his famous A Mexican Ulysses (1935) and the lucid criticism of racism contained in The Cosmic Race (1925).

However, the most famous aspect —perhaps the most important— of his legacy is what gives him a special place in history as an educator. He was our first Minister of Education and, as such, he undertook a campaign for popular education. He founded networks of libraries, normal schools and La Casa del Pueblo schools. He integrated and launched a collection of universal literature in a massive edition —with the works of Homer, Tagore, Goethe, Dante, among other masters of literature— that reached the entire country. He opened official buildings to the muralists in order to make them accessible to the people. He was a member of El Colegio Nacional and the Mexican Academy of Language. In addition, he was Dean of the National University. He can truly be considered an apostle of education.

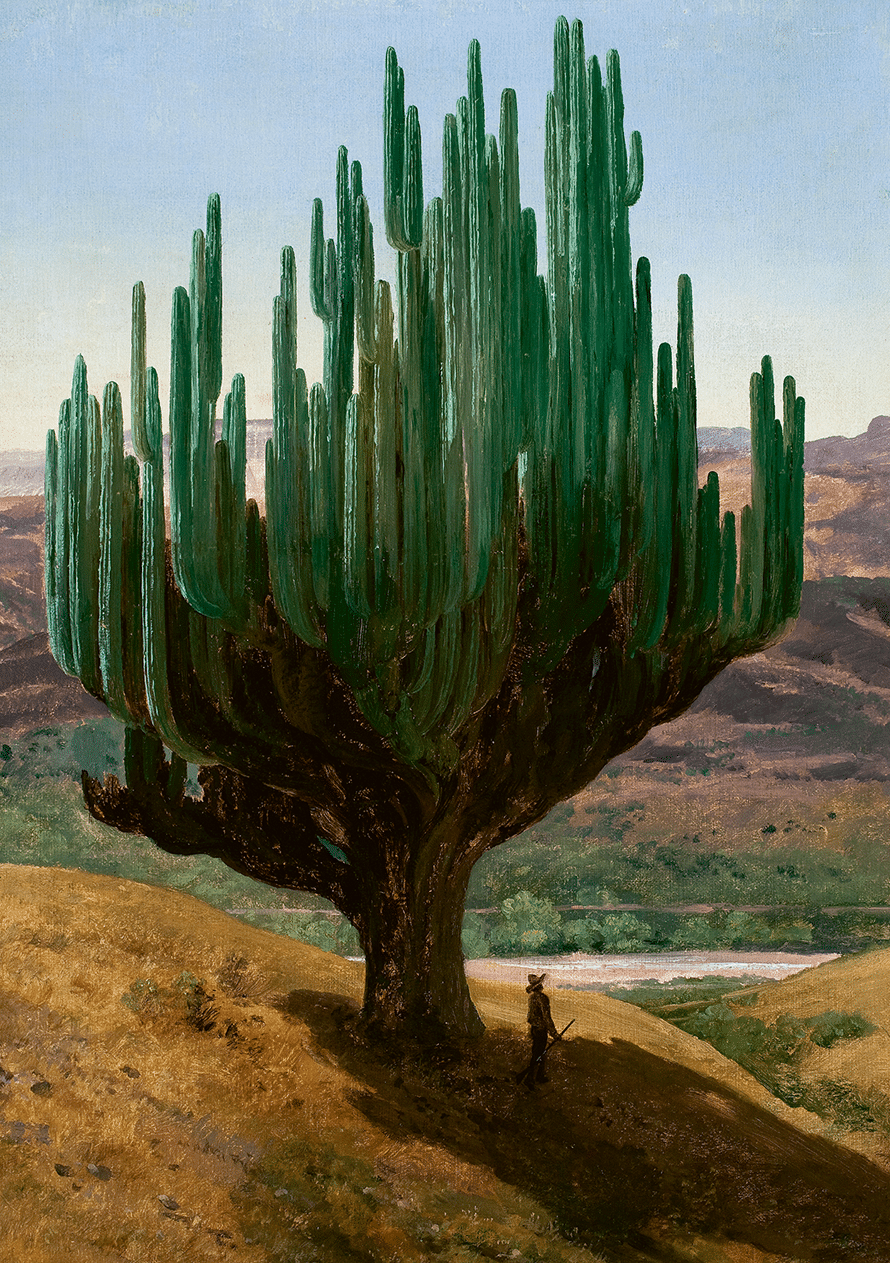

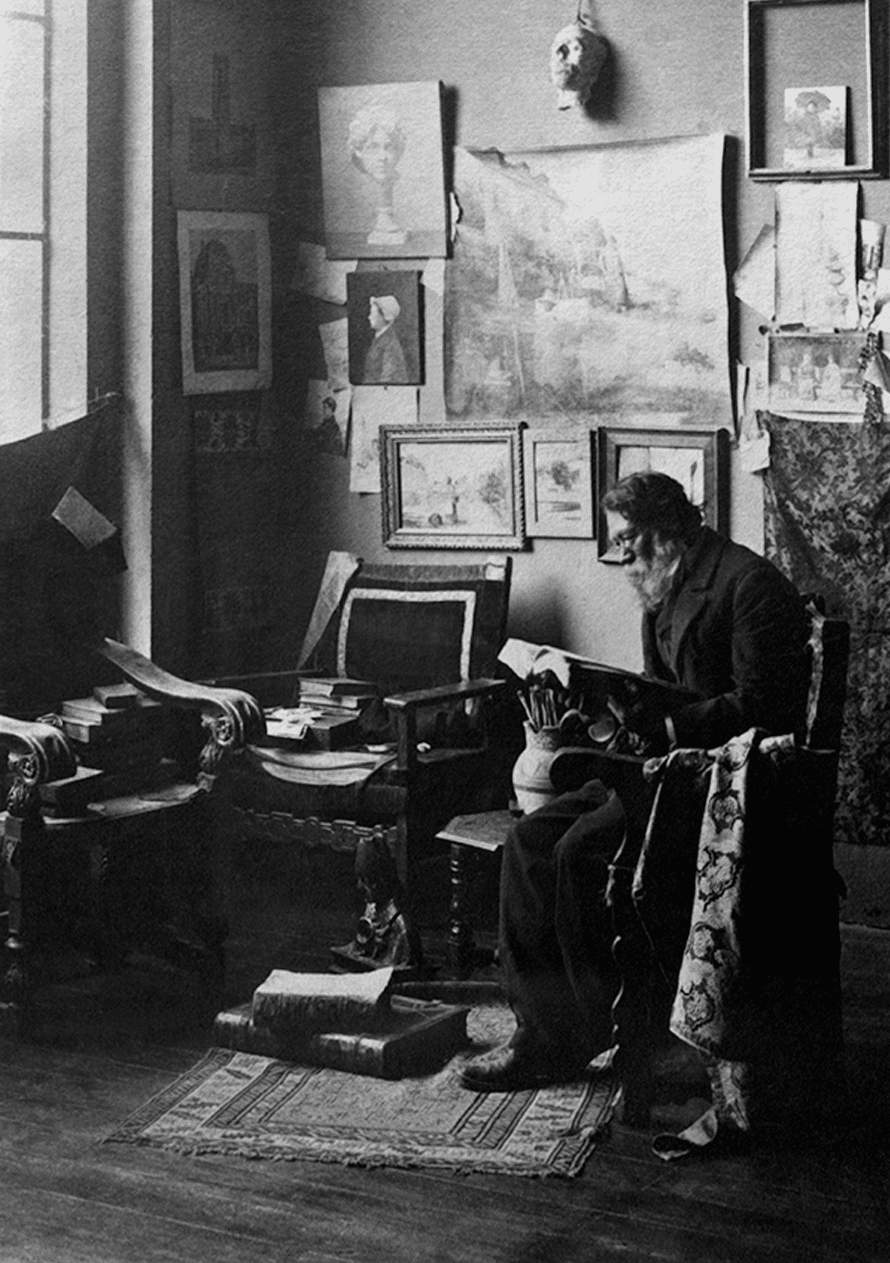

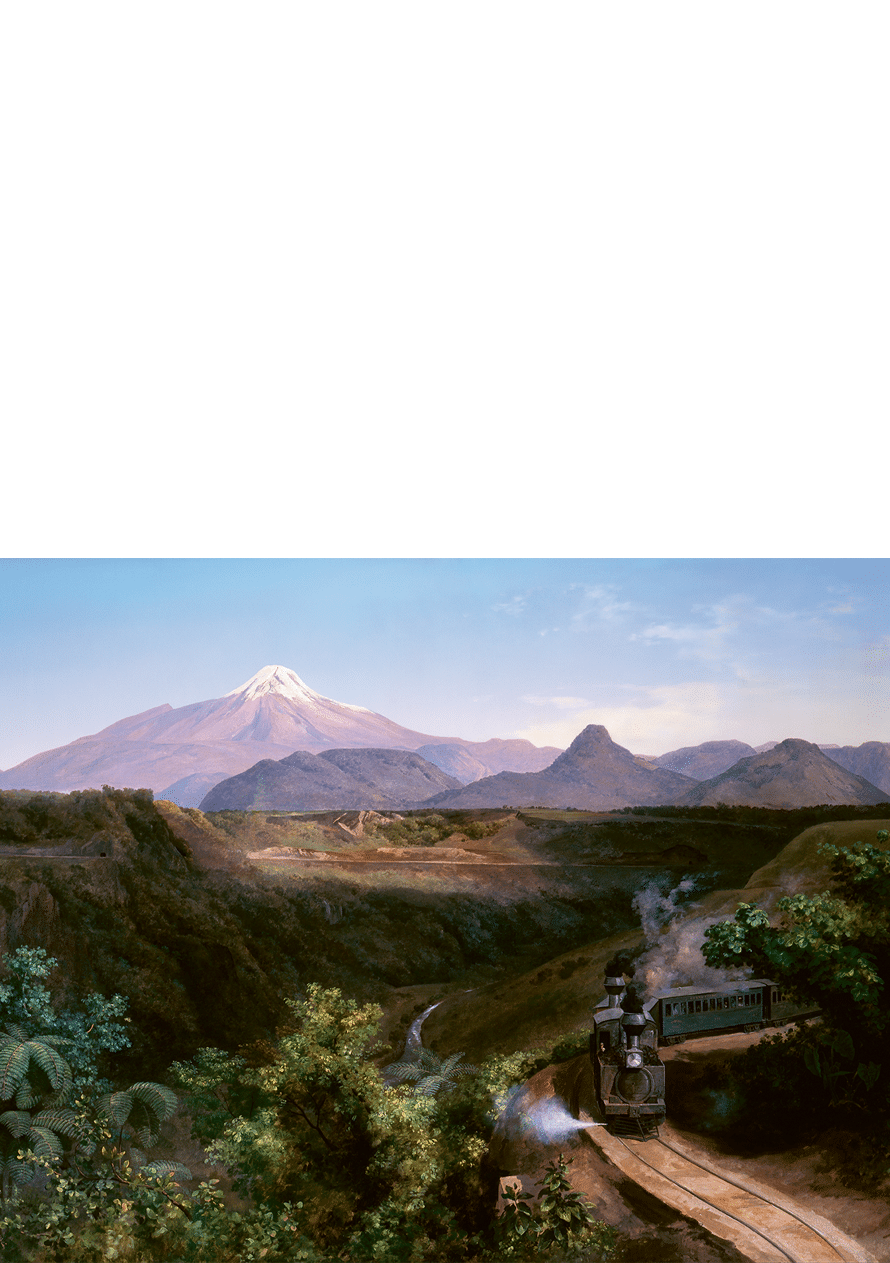

José María Velasco (1840–1912) was the greatest exponent of Mexican 19th century landscaping. Juan O’Gorman described him as one of the greatest painters in the world, whose work was not only to have painted landscapes “because there are thousands of painters who paint mountains, trees, ravines and landscapes, what Velasco did was to use the landscape to paint space. Space is the abstract theme of his painting […] with the color tone, he also painted time”.

He was born in Temascalcingo, State of Mexico, and studied night college at the School of Fine Arts of the Academy of San Carlos, and sold shawls during the day to make a living.

He was an innovator, while landscaping at that time was centered on the human figure, he focused his attention on nature and his vision was nourished by the studies he did in zoology, botany, geography and architecture.

In 1889 he was selected as head of the dele-gation that attended the Exposition Universelle of Paris, on the occasion of the centenary of the French Revolution. There he was appointed Knight of the National Order of the Legion of Honor. His work achieved universal recognition and put the name of Mexico on a par with Europe in the cultural field.

The creation of the most performed Mexican song in the world and the most famous Spanish language theme in history, “Bésame mucho” [Kiss Me a Lot] is owed to composer Consuelo Velázquez (1916–2005).

Originally from Ciudad Guzmán, Jalisco, Consuelito showed her musical talent from a young age; she said that she composed her flagship song as a teenager, during a break between piano lessons and, interestingly enough, had never kissed anyone.

“I didn’t even know what a kiss was, but it came deep from my heart […]. I couldn’t even think about that, I was educated in a school run by nuns”, she recalled in an interview. She also said that she was inspired by couples that had to separate during World War II. “Bésame mucho” has been translated into 20 languages and has about a thousand different interpretations, including those of Pedro Infante, Diana Ross, Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, Nat King Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., Ray Conniff, Andrea Bocelli, “Tin Tan” including The Beatles.

Some of her compositions include “Cachito”, “Que seas feliz”, “Amar y vivir”, “Enamorada”, “Contigo en la distancia”, “Bonito y sabroso” and “Piel canela”, among many more. She was a founding member and a lifetime honorary president of the Mexican Society of Authors and Composers (SACM); in 1977 she received the United Nations Peace Medal, and in 1992 the National Prize for Arts and Sciences.

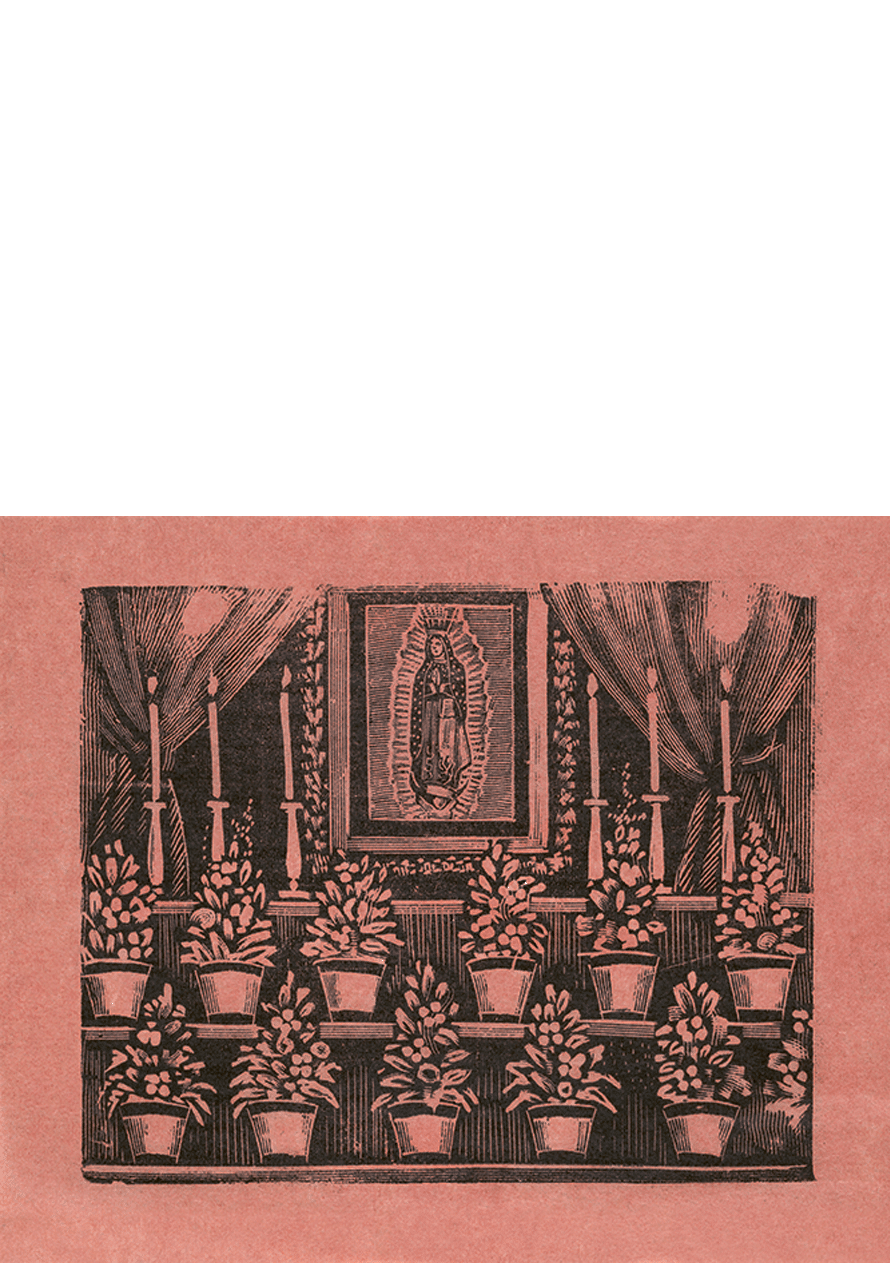

According to the Catholic faith, the dark-skinned Virgin appeared on the Tepeyac Hill before Juan Diego on four occasions. On the last one she asked him to visit Friar Juan de Zumárraga and left her image imprinted on his tilma or cloak in which the indigenous man carried flowers to offer to the first bishop of Mexico.

The story of these events was recorded on the Nican Mopohua, a document originally written in Nahuatl in 1556, currently protected in the New York Public Library.

But beyond religious belief, the dark-skinned Virgin, known today as the Virgin of Guadalupe, became a national symbol, linked to Mexico from its most intimate roots. From colonial times, passing through independent Mexico until our present time, she has been the banner of the army that sought the country’s independence, a miracle doer and an omnipresent image in Mexican homes.

In 1737, the Virgin of Guadalupe was proclaimed as patron of Mexico and December 12 was established as a holy day and national holiday. In 1754, pope Benedict XIV appointed her patron of New Spain —from Arizona to Costa Rica— and in 1945 pope Pius XII named her Empress of the Americas.

Although the Basilica in Mexico City is the main center of guadalupana devotion, receiving approximately six million pilgrims from all over the country and abroad every December 12, the Virgin’s image is also venerated in many churches, cathedrals and chapels around the world, including St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York and Notre-Dame in Paris.

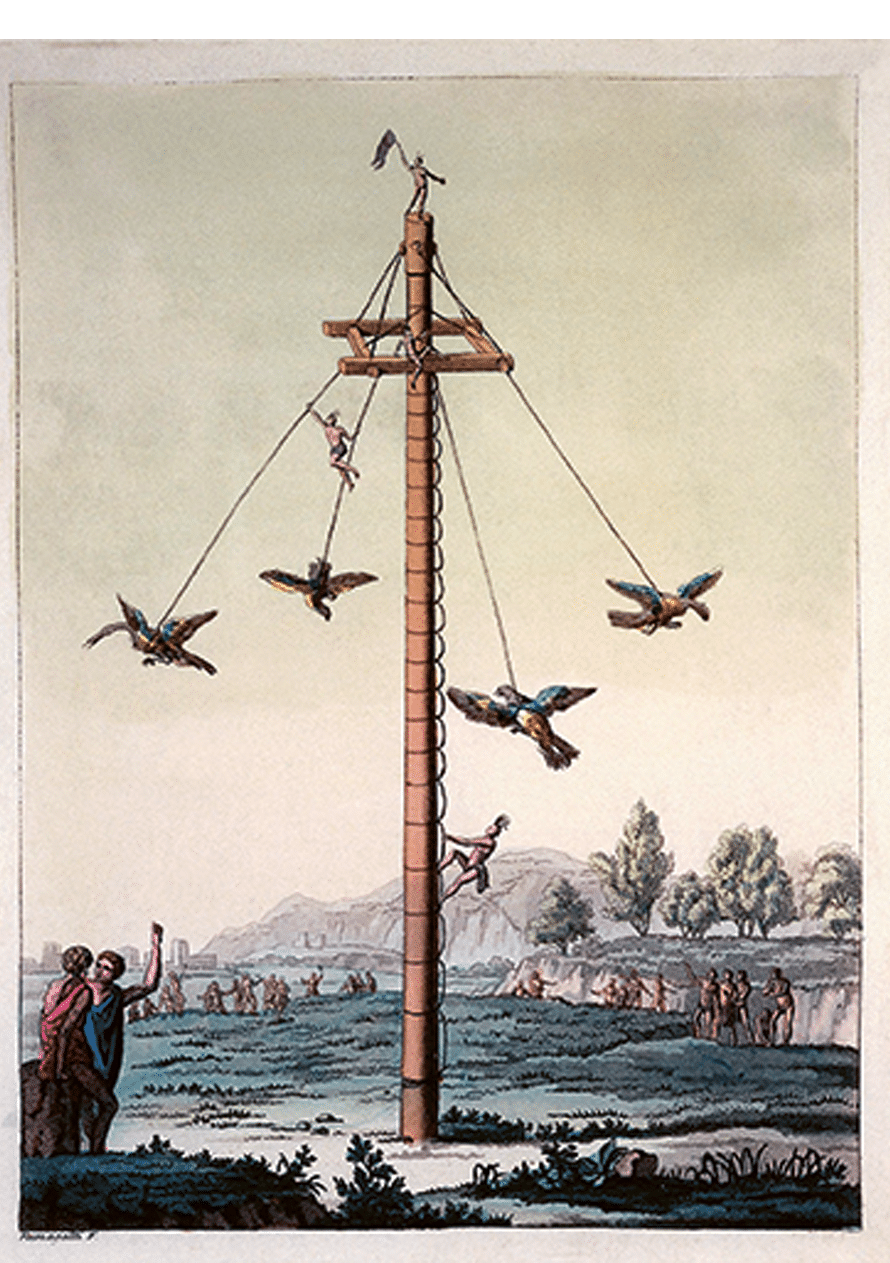

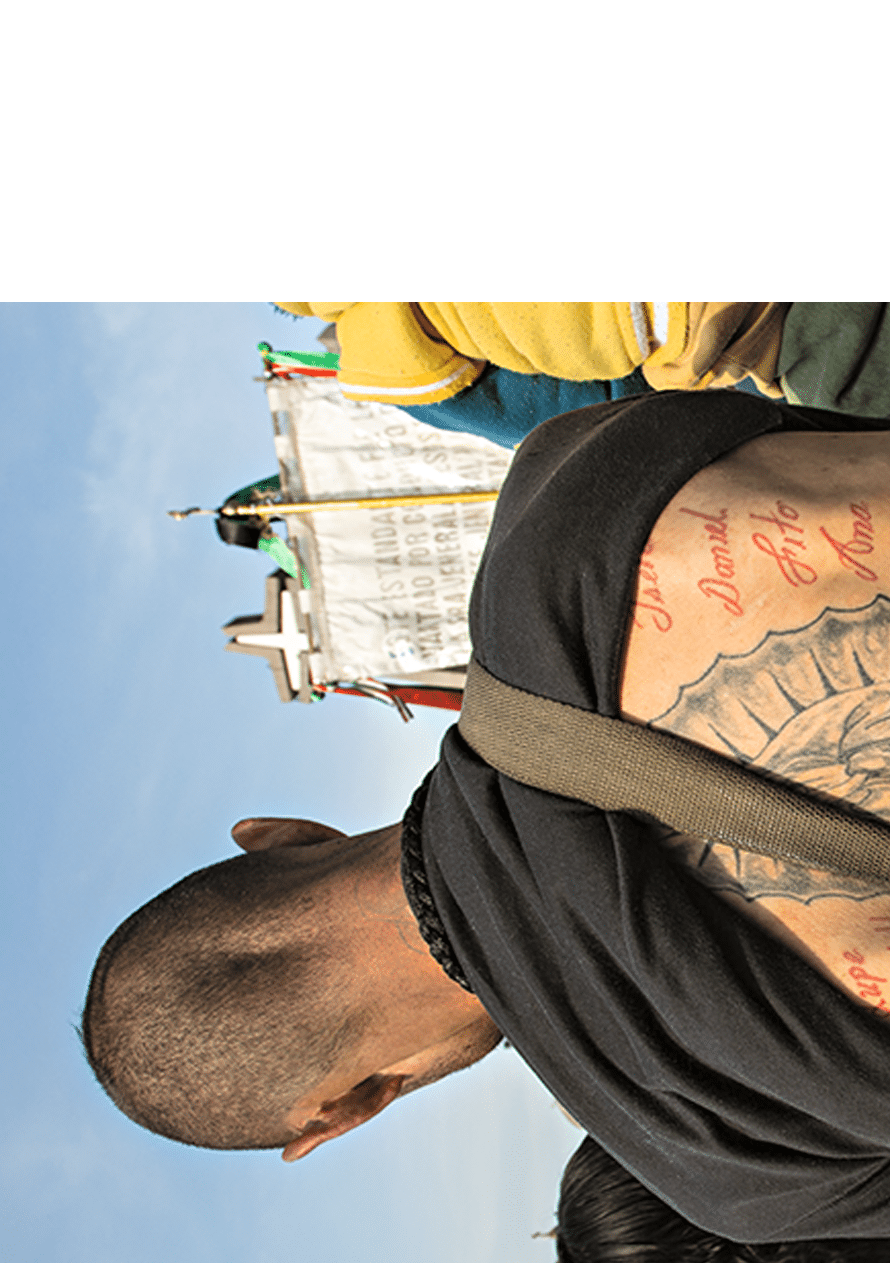

The Papantla Flyers ritual ceremony of pre-Hispanic origin is performmed by the Totonacs, Teenek, Nahuas, Ñañhus and Maya. With this fertiliy dance they seek to communicate with their gods and revive the myth of the universe. It conveys their cosmogony and community values.

During the ceremony, four young men climb up a pole of 18 to 40 meters high, made from the trunk of a tree recently cut in the forest —after having begged for forgiveness to the mountain god. A fifth man sits on the platform on the top of the pole, who is known as “the foreman” and plays melodies in honor of the Sun with a flute and drum.

After invoking the king star and all the elements, the four dancers fling themselves into the void from the platform, to which they are tied with long ropes that unroll as they rotate imitating the circular flight of birds, and gradually descend until they reach the ground.

The representative and emblematic value of this dance is most evident in the region of Totonacapan, in the state of Veracruz. There, over 500 flyers have been identified, distributed in different groups —more than 30 officially registered—. Nowadays there are three schools that teach children the ritual in its original form, along with the profound value of its meaning. In 2009 it was inscribed on the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.