According to the Popol Vuh poem when the gods gave rise to the Earth they decided to create man and to make him out of mud, but it lacked strength, so they later experimented with maize and thanks to the divine grain, man had the strength and sufficient intelligence to populate the world.

Maize is the greatest gift that Mexico has given the world. Thanks to its social, economic and cultural importance, it is the most representative crop in the country and its consumption is closely linked to Mexican history, traditions and gastronomy, both for its high nutritional value, and for its versatility and important healing properties.

It all started with teocintle, the wild maize seed that was domesticated about eight thousand years ago and the oldest vestiges of which were found in Tehuacán, Puebla. In Latin America alone, approximately 220 races of maize have been classified, of which 64 are produced in Mexico and 59 are exclusive to the country.

The variants of its use and consumption are countless: you can eat the cob (cooked or roasted); threshed, as esquites or in dishes such as pozole or maize soup, made with cacahuazintle maize. The dough from which tortillas, soups and other variants are produced is made from the ground grain.

The fungus that grows in maize is known as huitlacoche, “delicacy of the gods”. The ear is used to make atole andtamales —which are wrapped in maize leaves or totomoxtle. Maize “hair” has medicinal properties, especially useful to fight kidney diseases. The dried grains are considered “wise”, that is why they are used in ceremonial rites and serve in foretelling the future.

In 1970 Evangelina Villegas (Mexico City, 1924–2017) began collaborating with geneticist Surinder Vasal at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), with the aim of combining cereal chemistry with different techniques of cultivation to develop a variety of biofortified maize with high lysine and tryptophan content, essential amino acids that can reduce malnutrition.

Over two billion people in the world suffer from “hidden hunger”, since they consume a sufficient amount of calories, but not with the necessary nutrient combination, which causes serious health issues.32

Doctor Villegas and her team analyzed over 25 thousand samples of maize grains per year and provided Vasal’s team with data to sow or pollinate different experimental lineages. A decade later they were able to develop quality protein maize (QPM), a variety with twice as much lysine and tryptophan than conventional maize.

This achievement continues to be the basis for the development of biofortified foods, of which there are currently 290 varieties grown in 60 countries and reach approximately 10 million agricultural households.

Vasal and Villegas were jointly awarded the World Food Prize in 2000; Villegas became the first woman to receive this award, in addition to being included in the prestigious Alpha Delta Kappa list of International Distinguished Women.

Born in Yucatán, land of trova singers, Armando Manzanero (1935) is the author of more than 800 songs that have been translated into so many languages that he says he no longer remembers them all. Thanks to his work as a singer, songwriter, composer, musician and music producer, his name is among the great Latin American composers.

Among his hits there are more than fifty internationally famous songs, such as “No”, “Adoro”, “Somos novios”, “Esta tarde vi llover” or “Contigo aprendí”.

From Chavela Vargas to Frank Sinatra, passing through Elis Regina, Raphael, Los Panchos, Elvis Presley, Tony Bennet, Andrés Calamaro and many others, Manzanero’s songs have been interpreted with an infinite number of vocal ranges and musical arrangements, entrenched in the emotional memory of millions.

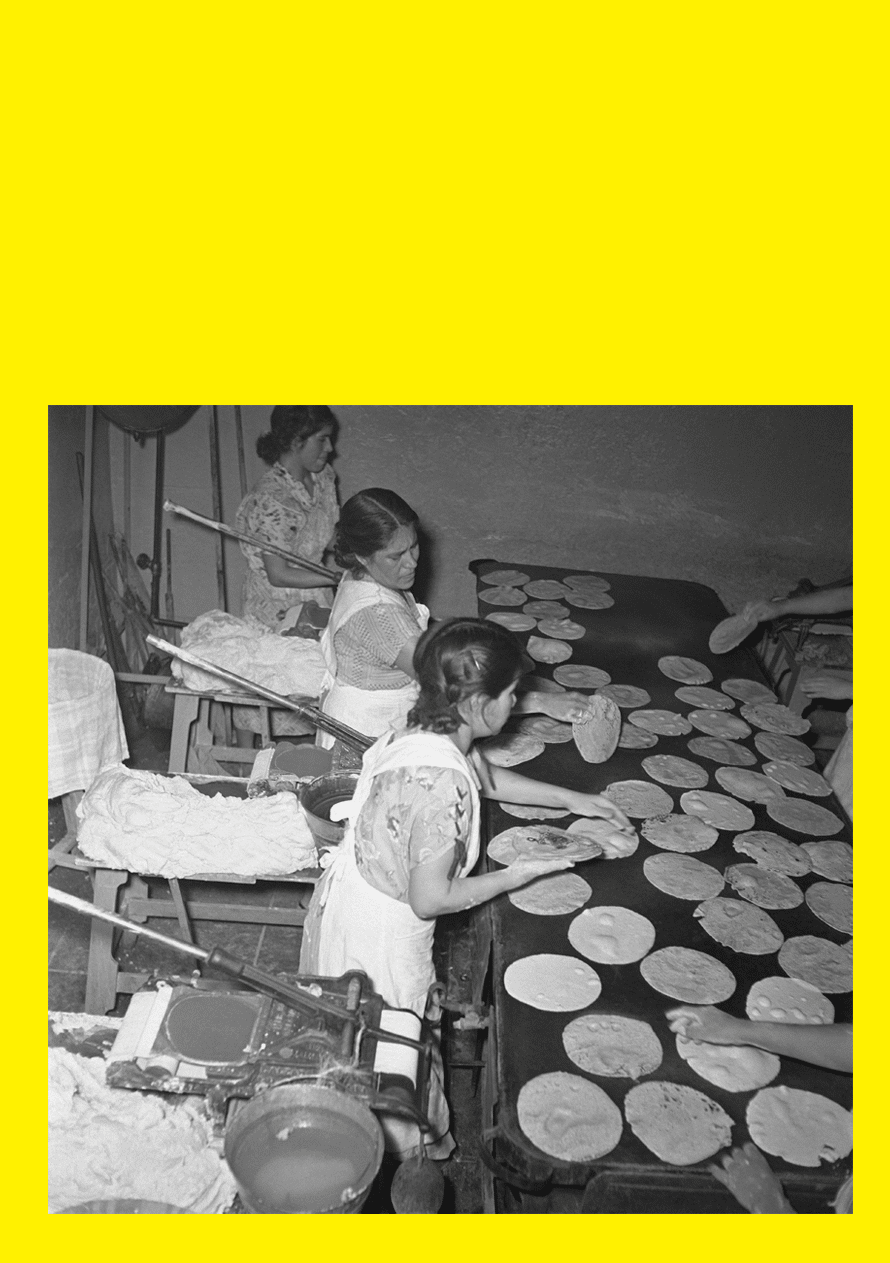

The first tortilla-making machine in Mexico was invented in 1904 by Everardo Rodríguez Arce and his partner Luis Romero. This first device produced square tortillas. The inventors sought to innovate not only the mode of production, but also the traditional shape of tortillas, arguing that the square was the ideal form for tacos. However, their proposal was not well accepted by customers, so they adapted a circular mold.

Thus began a long process of improvements and contributions in which several inventors intervened until 1947, when Fausto Celorio invented the first automatic machine, which consisted of a head of pressure-rolled rollers and a conveyor chain that reached a two-turn griddle capable of producing 16 thousand tortillas per day. The Celorio company continued to improve the process and, in 2001, launched into the world market a new model of compact tortilla-making machine that has taken the tortilla to unexpected places.

This cocktail, made of tequila, holds the eighth place among the best selling cocktails in the world. It was created by Daniel Negrete in 1936, when he worked at the Garci Crespo Hotel in Tehuacán, Puebla.

At the elegant bar of the hotel, the bartender met Margarita Orozco, a recurring guest who had the peculiar habit of accompanying her drinks with pinches of salt. One night, inspired by one of their long conversations, Daniel placed ice in a mixer, squeezed several limes, added Triple Sec, took a champagne glass and frosted its edges in a salt ring for Margarita's comfort, who no longer had to bother constantly reaching for the salt shaker.

María Sabina Magdalena García was born in Huautla de Jiménez, Oaxaca (1894–1985). She was a Mazateca healer and shaman, a wise woman who inherited the gift of healing through the balm of song and language. Throughout her life she served as a priestess guarding the great secrets of sacred fungi, known as “holy children”.

In the 1950s she became a national and international celebrity, after Robert Gordon Wasson and his wife Valentina Pavlovna —father and mother of ethnomicology— shared their traditional knowledge about the ceremonial and medicinal use of fungi in several publications. Thus began a parade of science, art, literature and entertainment celebrities that arrived in Oaxaca, searching for the shaman, including Albert Hofmann, Aldous Huxley, Walt Disney and The Beatles.

The poetic songs of María Sabina are part of an esoteric language that Mexican healers and priests know as hualtocaitl, the language of the Divine.

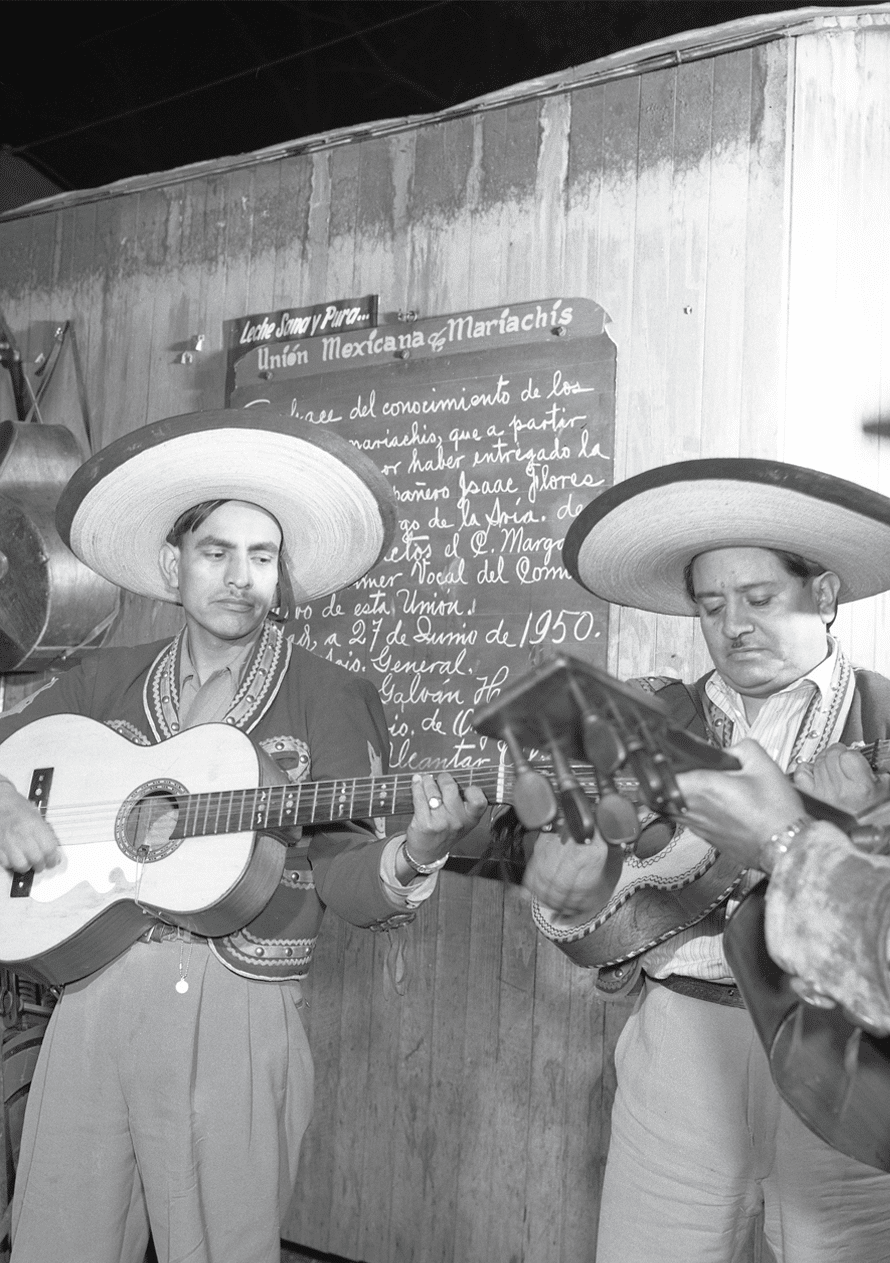

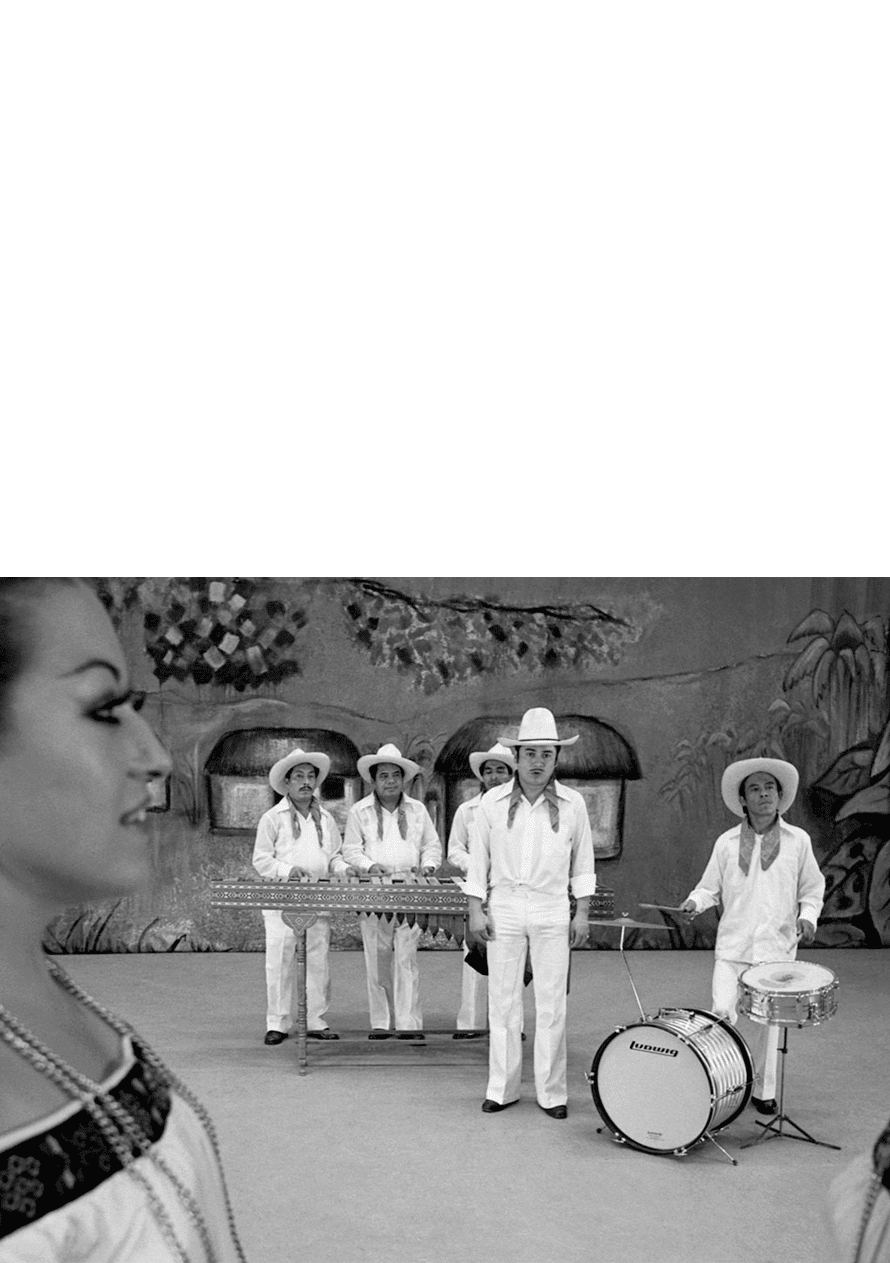

If you ask a foreigner to define Mexico, the answer will surely be that it is the land of tequila and mariachi. Considered Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO since 2011, mariachi is an essential element not only of our musical tradition, but of our culture.

Cocula, Jalisco, is the cradle of this genre that dates back to the viceregal era and mixes indigenous, European and African elements, combining the sounds of the violin, guitar, Mexican guitarron, vihuela, harp and trumpet. The latter is currently the flagship instrument of mariachi, but was not part of the original orchestration.

It was in 1941 when Miguel Martínez became the father of the mariachi trumpet when he first played this instrument with the Mariachi Vargas group in the XEW. Its inclusion was a suggestion of Emilio Azcárraga Vidaurreta, owner of the broadcasting company, in an attempt to face up to the impact of American music, plagued by wind brass instruments.

There are various theories about its name. Some claim that it is of Mayan origin, derived from the word mariamchi, that is, “those who have the same blood”, and another version attributes its origin to the French word mariage, which means “wedding” that began to be used in the 19th century when these groups provided entertainment at these events in the Highlands of Jalisco. Although it is very popular, mariachi history scholars reject the version of the French name because at that time, mariachi music was actually despised by the rancid Mexican aristocracy, which preferred European waltzes.

It all changed in 1936, when the Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán accompanied Lázaro Cárdenas during his presidential campaign tour. This enhanced the image of the mariachi and paved their way to the Golden Age of mexican film. Since then, its music has reached unexpected places, and crossed the language barrier. In Japan, for example, there is the popular Mariachi Samurai that performs songs both in Spanish and Japanese.

Central defender Rafael Márquez (Zamora, Mi-choacán, 1979) is the third Mexican soccer player with the highest number of international matches —148 in total— and is known as “the eternal captain” for holding the record of playing five World Cups with this investiture.

Márquez began playing as a professional soccer player in the ranks of Atlas in Guadalajara, where he made his debut at age 17, in 1996. That same year he was selected for the national team. Thanks to his outstanding performance with the Aztec national team he drew the attention of European clubs. The French team Monaco was the first to integrate him into its ranks, after paying four million dollars for his transfer fee in the 1999-2000 season. Then he played for FC Barcelona, the New York Red Bulls and Hellas Verona.

As member and captain of the Mexican national team, he was champion of the Confederations Cup (1999), won the Gold Cup (2003 and 2011) and the CONCACAF Cup (2015), in addition to reaching the Copa America sub-championship (2001). He was considered one of the top international players until his retirement, at the 2018 World Cup.

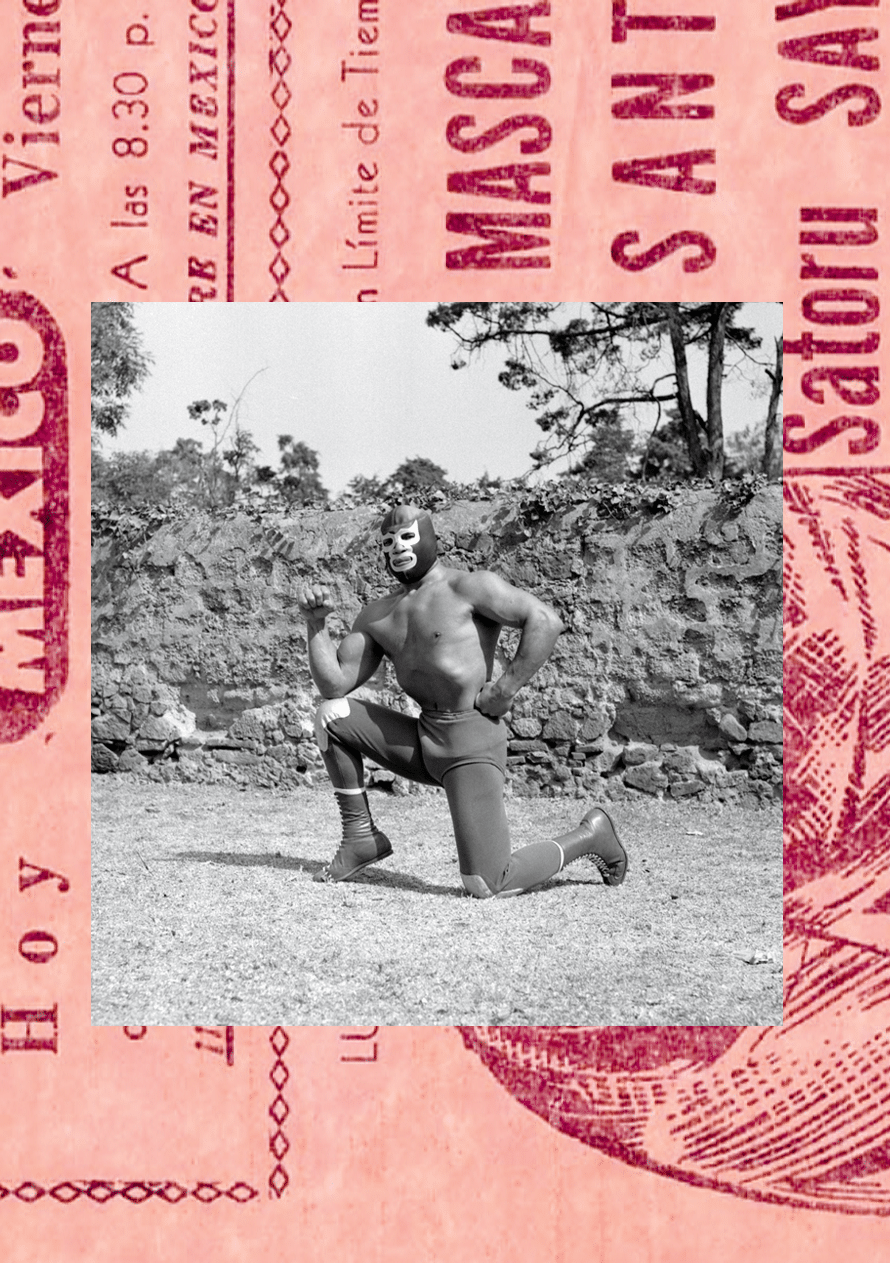

Lucha libre is a version of Olympic wrestling that is practiced in several Latin American countries. However, one of its essential elements is purely Mexican: the mask.

The first wrestler who created a character hiding behind a mask to protect his identity was Ciclón McKey. It was the 1930s and the wrestler went to Antonio H. Martínez, a shoemaker from León who lived in Mexico City, to have him design an accessory that would cover his face. Ciclón McKey appeared in the ring using a four-hole goatskin mask, and he was so successful that he changed his name to “La Maravilla Enmascarada” [Masked Wonder].

The power of the mask captivated the audience and other wrestlers began to use it: Black Shadow, Rayo de Jalisco, Blue Demon and the legendary Santo, “The Silver Masked”, among many others. They were no longer men but legends, whose masks became cultural symbols that have influenced art, film and international advertising.

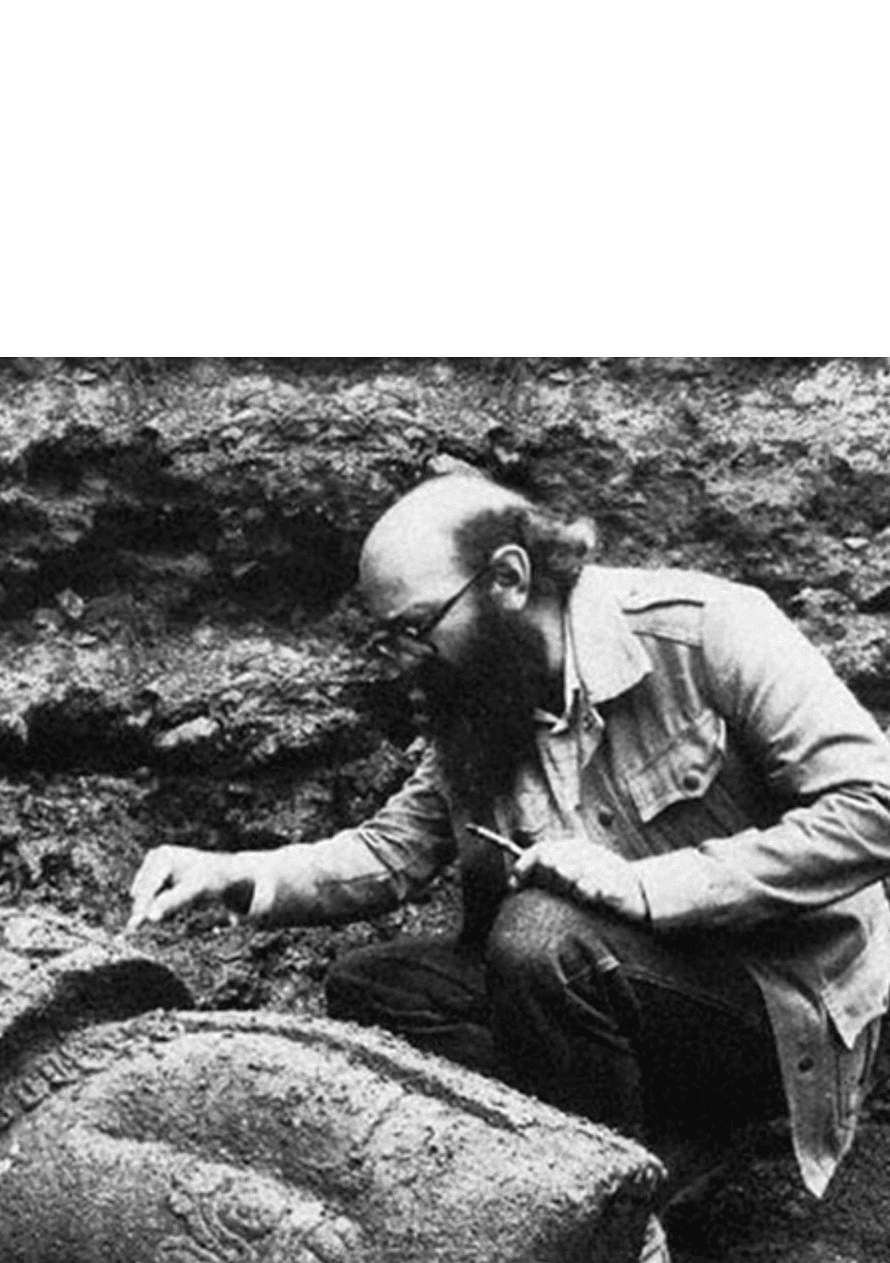

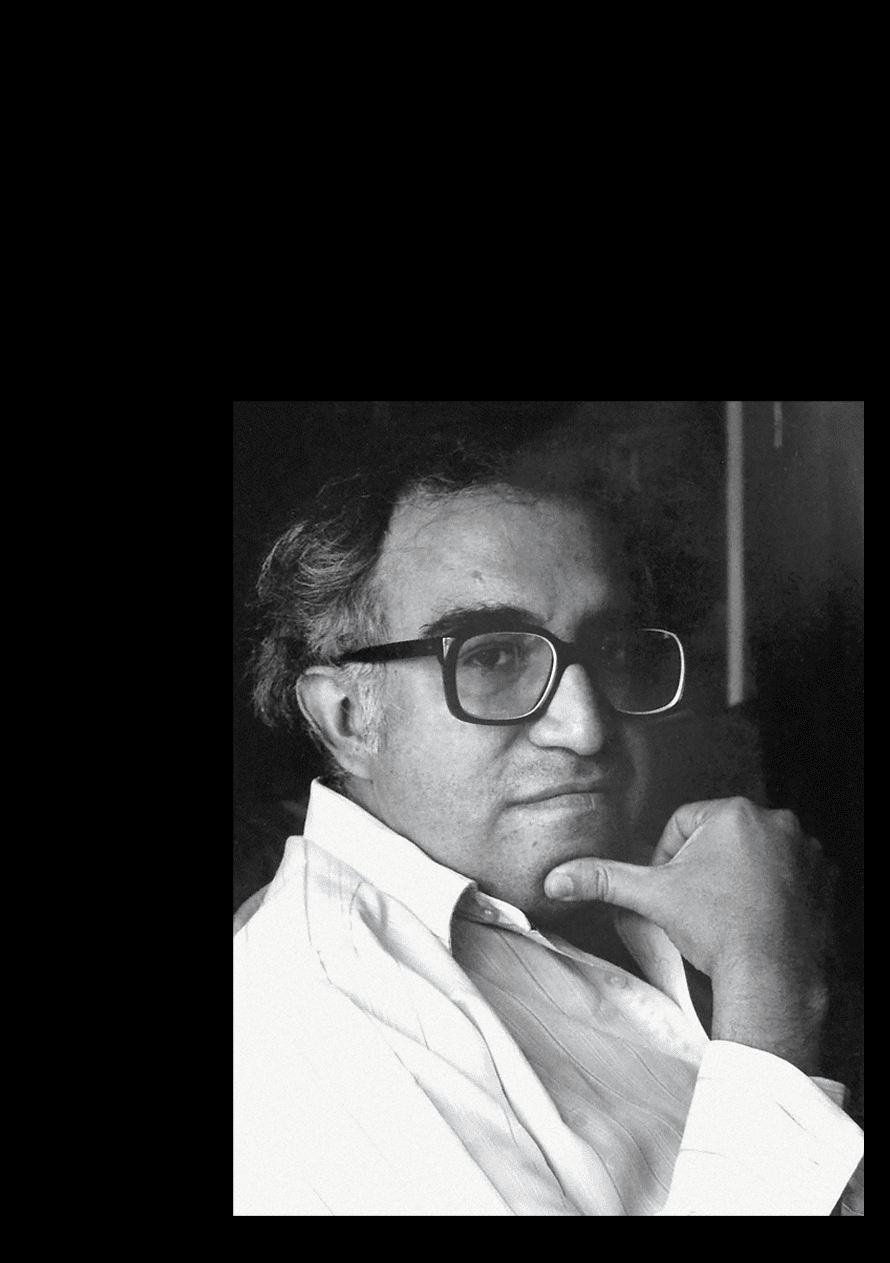

Eduardo Matos Moctezuma’s (Mexico City, 1940) found his passion for archeology through a book: Gods, Graves and Scholars, by C. W. Ceram, a popular science text that unveiled the archaeological secrets of great civilizations.

At the beginning of the 1960s he began to work in the excavations of Tlatelolco, under the direction of archaeologist Francisco González Rull. Later, in 1978, he took over the coordination of the Templo Mayor Project, after opposing the reconstruction of the temple to favor the conservation of the ruins as witnesses of the violent encounter between two cultures. In recognition of his work on this project, Time magazine named him “Moctezuma III”.

Since then, he has published books such as Teotihuacán: The City of Gods (1990), Life and Death in the Templo Mayor (1995), Las piedras negadas: de la Coatlicue al Templo Mayor (1998) and Estudios mexicas (2006), which are among hundreds of books, theses and studies dedicated to the research and dissemination of this matter written by him and his collaborators.

Throughout his career he has served as president of the Archeology Council and director of the National Museum of Anthropology and History, among many others. He has been awarded the National Prize for Arts and Sciences in the field of History, Social Sciences and Philosophy (2007), and the Premio Crónica (2017). In the year 2017, Harvard University inaugurated a chair with his name, making him the first Mexican to receive such a distinction.

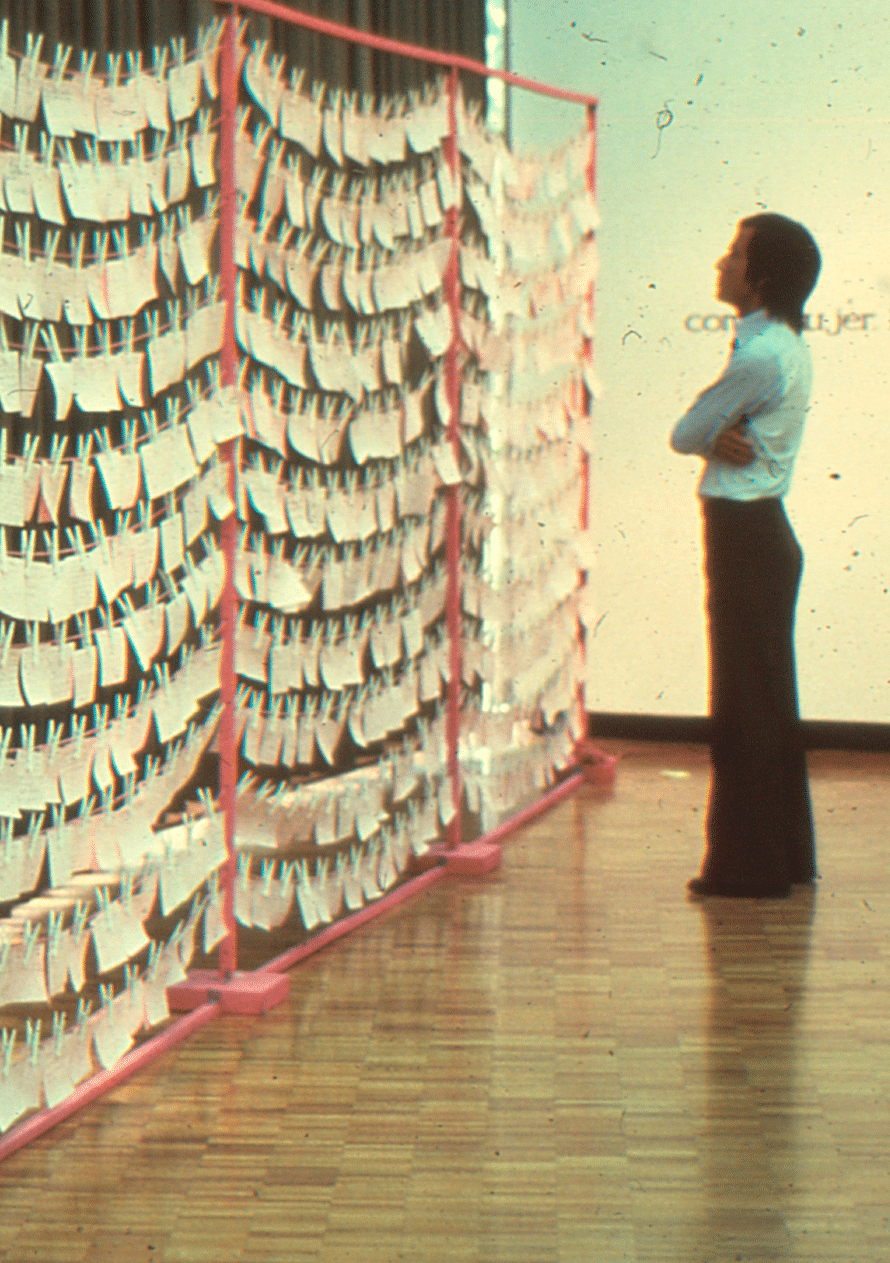

Mónica Mayer (Mexico City, 1954) is a pioneer of feminist art and performance in Mexico and Latin America. As an artist, woman, mother and human being, one of her most important battles has been against invisibility, therefore her proposal insists on building narratives that transform the image historically imposed on women.

Together with Maris Bustamante, she founded the first feminist art collective in Mexico in 1983: Polvo de Gallina Negra. The most famous project of this group was MADRES!, an exploration of motherhood for which both artists became pregnant to observe the experience from a sociological point of view. Part of this initiative included the experiment “Mother for a day”, which entailed a dozen men carrying an artificial belly, among the participants was journalist Guillermo Ochoa, who performed it live on national television in 1987. Notes and collected material have been presented in venues such as the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, in Spain.

In 1989, along with Víctor Lerma, she created Pinto mi raya, a conceptual art project that includes an important archive resulting from research on Mexican contemporary art that began in 1991 and that, to date, includes more than 200 thousand articles.

Her work has been presented in important international exhibitions such as WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution, in the United States and Canada, or La Batalla de los Géneros at the Centro Gallego de Arte Contemporáneo, among others.

Born in Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, in 1960, Abigail is the most important figure among traditional cooks in Mexico. In 1993, her restaurant Tlamanalli was listed by The New York Times as one of humanity’s ten essential epicurean pilgrimages and since then, she has traveled the five continents in order to share the tradition and cuisine of Mexico and Oaxaca in an endless number of congresses, festivals and diplomatic representations.

She says she learned to cook before she could talk or walk. She was cradled in the family kitchen among the smell of chili, the sound of maize crushed on the grinding stone and the cooing of Zapotec songs. At age six she already knew how to make a tortilla and identified all the ingredients to prepare black mole.

Some say that Abigail was chosen by the Zapotec gods to protect the pre-Hispanic culinary wisdom and traditions of their culture, since the most important thing for her is the passing on of values, food, tradition and language, which make up the identity of her people to the new generations.

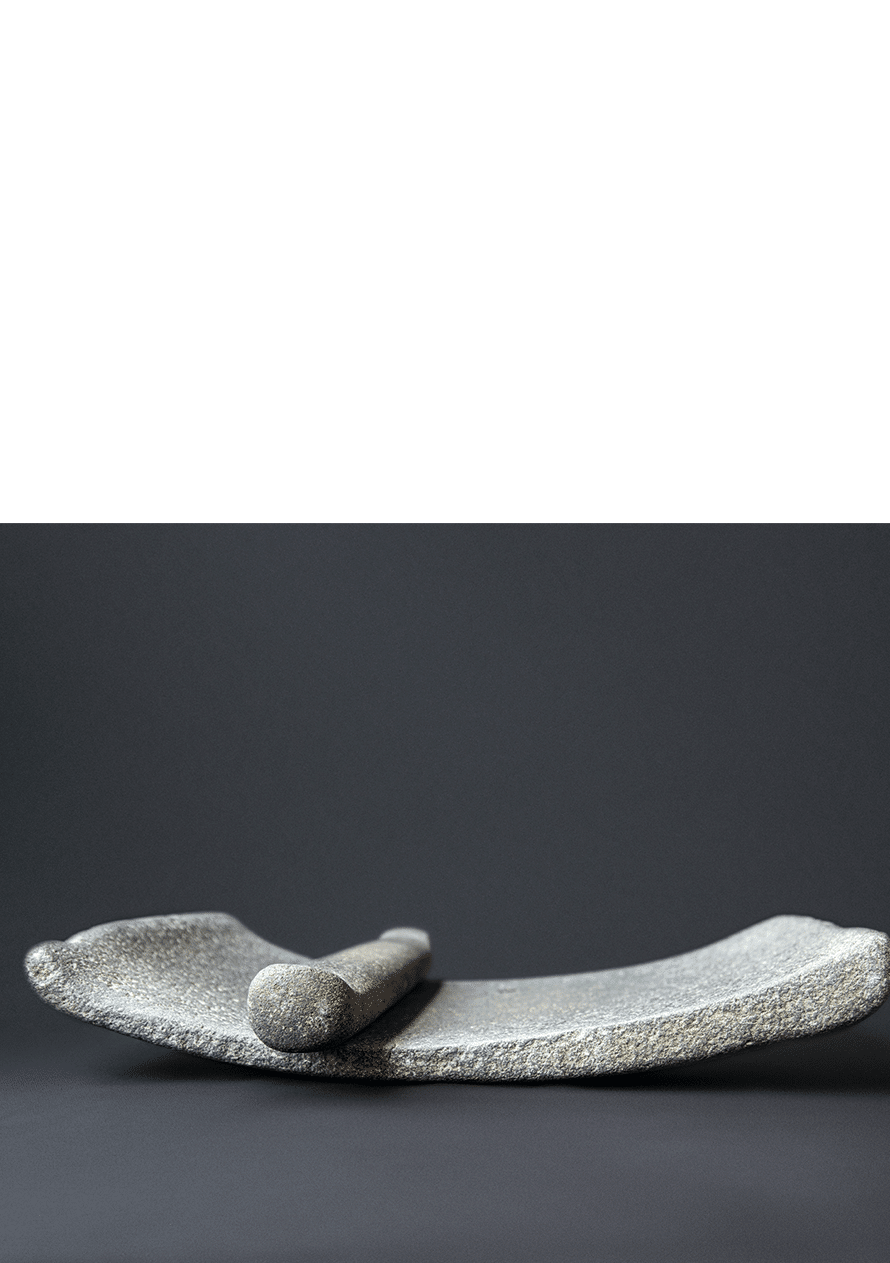

The grinding stone or metate is a traditional utensil made with a rectangular volcanic rock, which is used for grinding ingredients with the help of a cylindrical rock known as metlapil or metate hand. It is believed that its invention promoted the increase in seed consumption in pre-Columbian Mexico, a fact linked to the development of maize domestication.

Its use represents one of the most important gastronomic rituals in the country. Metates are used to grind ingredients, mainly maize and cacao, although it is also used to extract mineral and vegetable pigments.

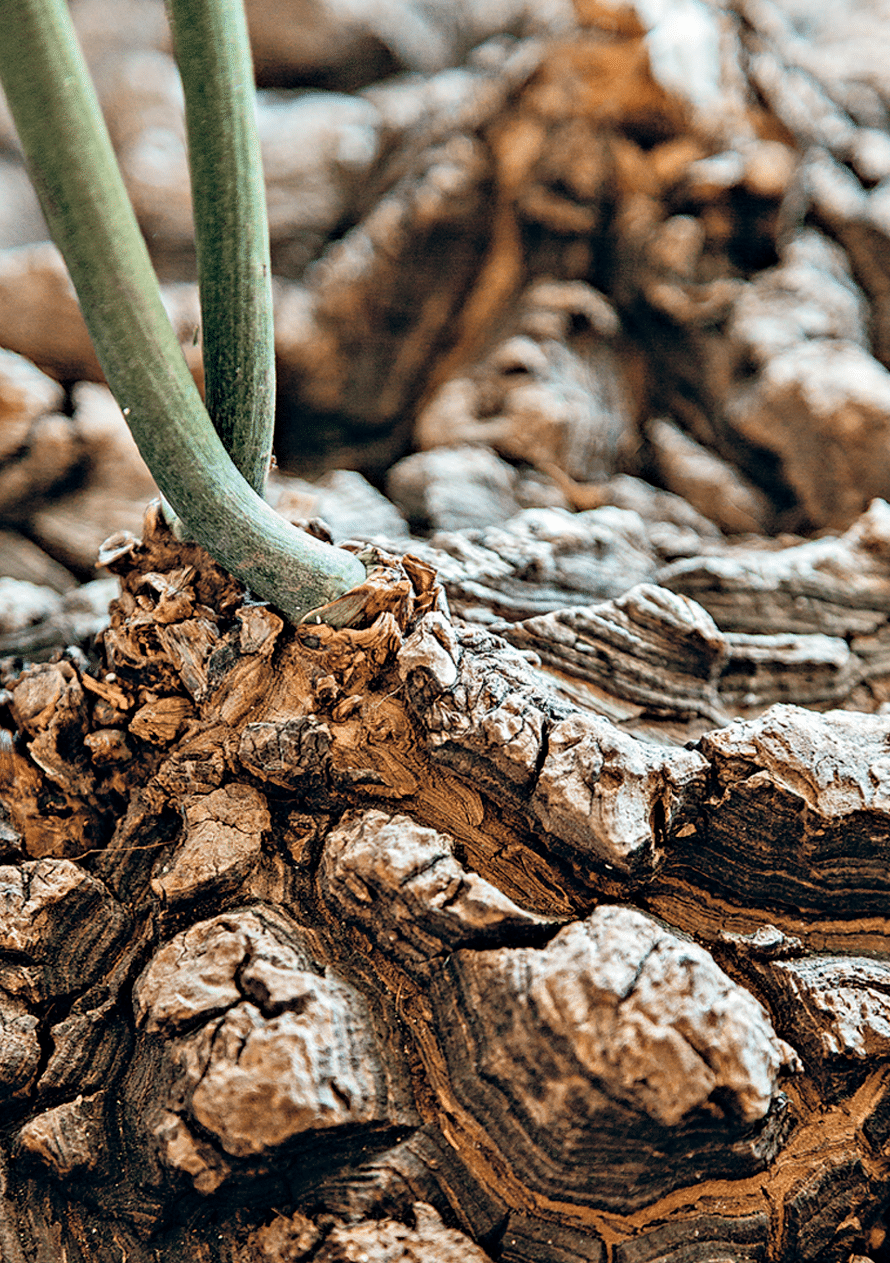

This mestizo drink was born thanks to the arrival of the still and distillation system in New Spain. At present, a distinction is usually made between mezcal and tequila, but in reality “mezcal” refers to all spirits that are obtained from the various types of agave, including tequila, the fame of which has overshadowed its congeners.

The generic name comes from the Nahuatl mexcalli, which means “cooked maguey ribs”. However, each mezcal is named according to its native region: bacanora, in Sonora; xtabentun, in Yucatán; sotol, in Chihuahua; charanda, in Michoacán; tequila, in Jalisco; or comiteco, in Chiapas —to name a few. Mezcal, par excellence, is produced in Oaxaca, where it is still respected as a ritual drink in the Zapotec indigenous culture.

The chemist from Nayarit, Luis Ernesto Miramontes Cárdenas (1925–2004), was only 26 years old when he placed the name of our country on the scientific map of the 20th century, thanks to his discoveries derived from barbasco, one of the most important Mexican endemic plants for the pharmaceutical industry.

On October 15, 1951 he first synthesized norethisterone, a compound considered one of the 17 most important molecules in the history of mankind, since it consolidated a series of medical advances that included the treatment of endometriosis, female hormonal regulation and the invention of the first synthetic oral contraceptive.

Miramontes is, so far, the only Mexican included in the U.S. Inventors Hall of Fame —along with Louis Pasteur and Thomas Alva Edison— and has been acknowledged as one of the most important scientists in the history of humanity.

He was founder of the UNAM’S Chemistry Institute and accumulated throughout his life an extensive number of publications, as well as almost forty national and international patents in areas such as organic chemistry, pharmaceutics and petrochemistry.

After more than 70 years of exclusive exploitation in Mexico, barbasco is still used in the industrial production of steroid hormones, and new uses and properties are discovered every day; for example, its molecules, in contact with other compounds, can be used to fight cancer cells. It grows in states like Oaxaca, Veracruz, Puebla, Tabasco and Chiapas.

The molcajete is a concave stone vessel —similar to a mortar—, supported by three short legs, which is complemented by a teojolote or stone pestle to crush ingredients. It has been used since pre-Hispanic times to grind and mix small amounts of grains and spices, as well as to make sauces. Its name comes from the Nahuatl molcaxitl, composed of the words molli (sauce) and caxitl (casserole).

The most traditional ones are made of basalt, a volcanic rock extracted from the mines of San Lucas Evangelista, municipality of Tlajomulco de Zúñiga, in Jalisco, although there are also some made of clay.

Over time, the molcajete has become a symbol of Mexican cuisine not only for its ancient use, but also for its design. Something common in taco restaurants, diners and food stands in Mexico are plastic molcajetes used as containers to serve guacamole, sauces and other complements.

Under this name that comes from the Nahuatl molli, meaning “salsa” or “stew”, an infinite number of complex dishes of pre-Hispanic origin come together, representing an important part of the identity of several regions of the country.

Originally, moles were prepared for the gods, based on a series of ingredients crushed and mixed in a metate. Historian Cristina Barros tells that Pochtecas, upon arriving at their home after a journey, offered “chicken heads in caxetes with their molli” to Xiuhtecuhtli, god of fire.33 Currently, there are moles for every occasion, although in many traditions their consumption is reserved for celebrations or rituals.

In Oaxaca, they preserve the legacy of the seven moles: black, coloradito, red, yellow, green, chichilo and manchamanteles [tablecloth stainer], present at the festivals of each region; while Puebla is the cradle of the famous poblano mole, a variation of the pre-Hispanic mole, legacy of the nuns of the convent of Santa Rosa that includes over 22 ingredients.

There are also the mole de panza, mole de olla or the michmole, which in their preparation are more similar to a substantial soup. The Diccionario enciclopédico de la gastronomía mexicana has records of over 90 varieties of this dish.

Doctor Mario Molina (Mexico City, 1943) is a pioneer and one of the world’s leading researchers in atmospheric chemistry.

In 1974, he co-authored, along with F. S. Rowland, the original article that predicted the thinning of the ozone layer as a result of industrial gas chlorofluorocarbon (CFCs) emissions. It was an unknown topic and difficult to understand even for the scientific community: invisible compounds attacking an invisible layer, which protects us from invisible radiation (ultraviolet rays). This earned them the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, in 1995.

His research and publications on the subject promoted the establishment of the United Nations Montreal Protocol, the first international treaty that has effectively faced an environmental problem of global scale and of anthropogenic origin.

Since then, he has devoted himself to work against climate change and in favor of the rational use of resources and renewable energy. In addition to disseminating the subject and working as an advisor to great world leaders, in 2004 he founded the Mario Molina Center, a civil association dedicated to finding practical, realistic and substantive solutions to issues related to environmental protection, the use of energy and climate change prevention.

José Pablo Moncayo García (Guadalajara, Jalisco, 1912–Mexico City, 1958) is one of the most important representatives of Mexican musical nationalism of the 20th century,34 creator of “Huapango”, a work that has earned the title of Mexico’s second national anthem.

Besides being a composer, percussionist, music teacher and conductor, Moncayo was a lover of Mexican landscape. As an amateur mountaineer he climbed the Popocatépetl, the Iztaccíhuatl and the Pico de Orizaba, collecting images and atmospheres that he managed to capture in his compositions.

It was Carlos Chávez who asked him to carry out musical research in Veracruz. Thanks to this assignment, the composer studied songs such as “Ziqui ziri”, “Balajú” and “El Gavilancito”, which influenced the creation of “Huapango”, premiered on August 15, 1941 at the Palace of Fine Arts, with the Mexican Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Carlos Chávez. Within his musical legacy, masterpieces such as “Muros verdes”, “Tierra”, “Hueyapan” and “Amatzinac” are also remembered.

Carlos Monsiváis (Mexico City, 1938–2010) was one of the most influential writers in Latin America. He managed to forge an endless production of millions of words, in thousands of texts that blurred the border between chronicle, journalism and literature, and through which he deciphered Mexican culture.

“Monsi”, as he was known, was essentially a collector. Endowed with a prodigious memory, he could recite entire verses of the Bible, poems, historical data, jokes and all kinds of anecdotes —his own or somebody else’s— which he treasured as well as his collection of books, documents, toys, photographs, cartoons, art and objects that add up to over twenty thousand pieces, now protected in the Museo del Estanquillo.

The “Favorite Son” of the Portales neighborhood in Mexico City, cleverly described city happenings through varied resources, from critical historical analysis to ironic metaphors, praise and mockery, becoming an essential figure in national culture.

His chronicles are part of the education of Mexicans and have shed light on the meaning of Mexicanness. It is said that the city loved him so much that it granted him the gift of ubiquity, so he could see and be seen at the same time in several places. His work is grouped into books such as Días de guardar (1970) and Escenas de pudor y liviandad (1981-1988).

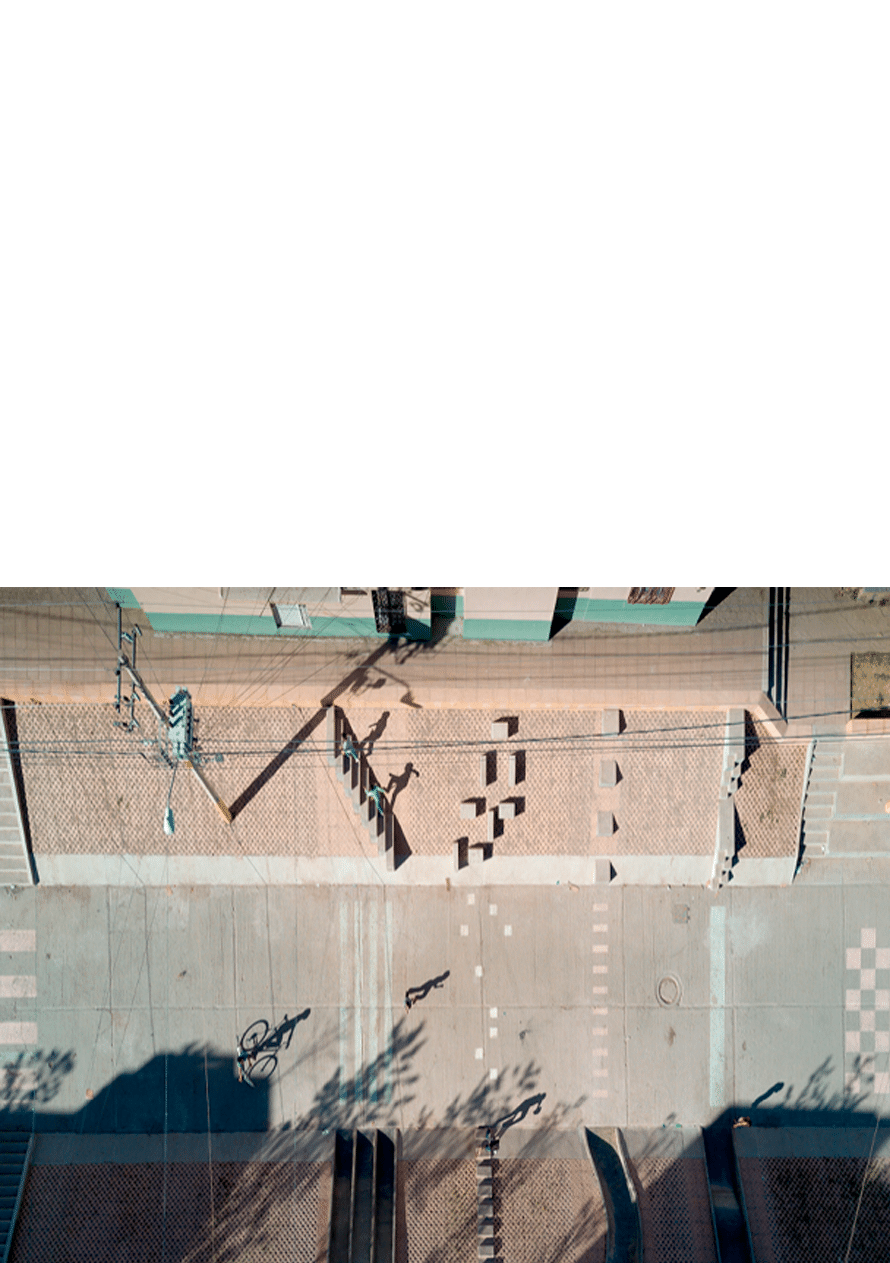

For Rozana Montiel, architecture goes far beyond building: it is related to social construction, with the “simple fact of drawing a line and generating space through other means”. She is an architect from the Universidad Iberoamericana and has a master’s degree in Architecture, Criticism and Project from the Universitat Politécnica de Catalunya UPC, in Barcelona, Spain.

Winner of the Moira Gemmill Prize for Emerging Architecture (2014) awarded by The Architectural Review in London, and the Emerging Voices Award (2016) awarded by The Architectural League of New York; she was also selected by the Rockefeller Foundation for an artistic research residence in Italy (2017) and recently received the 2019 Global Award for Sustainable Architecture, a distinction that every year awards five architects who contribute to a more equitable and sustainable development in the world.

She directs her own studio specializing in design and public space. Her interest in architecture involves working with other disciplines through an active look. She is also involved in various projects of different scales and strata that range from the city to the book, the artifact and other micro-objects. Among her projects are Vacío circular, an adaptation of the Pilgrim’s Route in Jalisco, and Cancha, a social-interest housing unit in Veracruz.

This plump doll —made of rag, yarn, and colored ribbons that bind its braids or crown its head— is a traditional craft practice, inherited from the Mazahua culture.

Its origin dates back to the time of the Conquest and is located in the region of Michoacán and the State of Mexico. It is believed that its earlier versions included materials such as clay, palm and maize “hairs”. The first name it became known as, was “María”, in honor of the Mazahua artisans who used to sell them on the streets of the Mexican capital.

The legacy of its production is preserved thanks to artisans of Amealco, Querétaro, where it was adopted by the Otomi communities. There it is know as “Lele” and they make her together with “Dönxu”, the traditional Otomi doll.

Chef, researcher, gastronomic historian and writer, Ricardo Muñoz Zurita has dedicated his career to becoming one of the great custodians of the ancient knowledge of alchemy and traditional Mexican cuisine.

He is originally from Macuspana, Tabasco, but grew up in Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz, so his palate was educated among the flavors of two of the country’s great culinary cultures; that is why he felt very disappointed when he noticed the contempt that many showed towards Mexican cuisine by not considering it within the canon of world “haute cuisine”.

In search of insights that he did not find in his studies at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris or at The Culinary Institute of America in New York, he delved into villages and ranches looking for traditional cooks who shared with him recipes, techniques, ingredients, utensils, practices and customs. From his notes and manuscripts —which he accumulated in just over two decades of travel— emerged the Diccionario enciclopédico de la gastronomía mexicana (2012), a document unique in its kind. He is also the author of a dozen books regarding Mexican cuisine, among which are: Los chiles rellenos en México, antología de recetas (1996) and La Cocina Mexicana: Many Cultures, One Cuisine (2012).

He was named by Time magazine the “Prophet and Preserver of a culinary tradition”, and he is considered one of the top chefs of Mexico and Latin America. He is a member of L’ Académie Culinaire de France and currently directs, as owner chef, Azul y Oro coffee shops, at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, and the Azul Condesa and Azul Histórico restaurants.

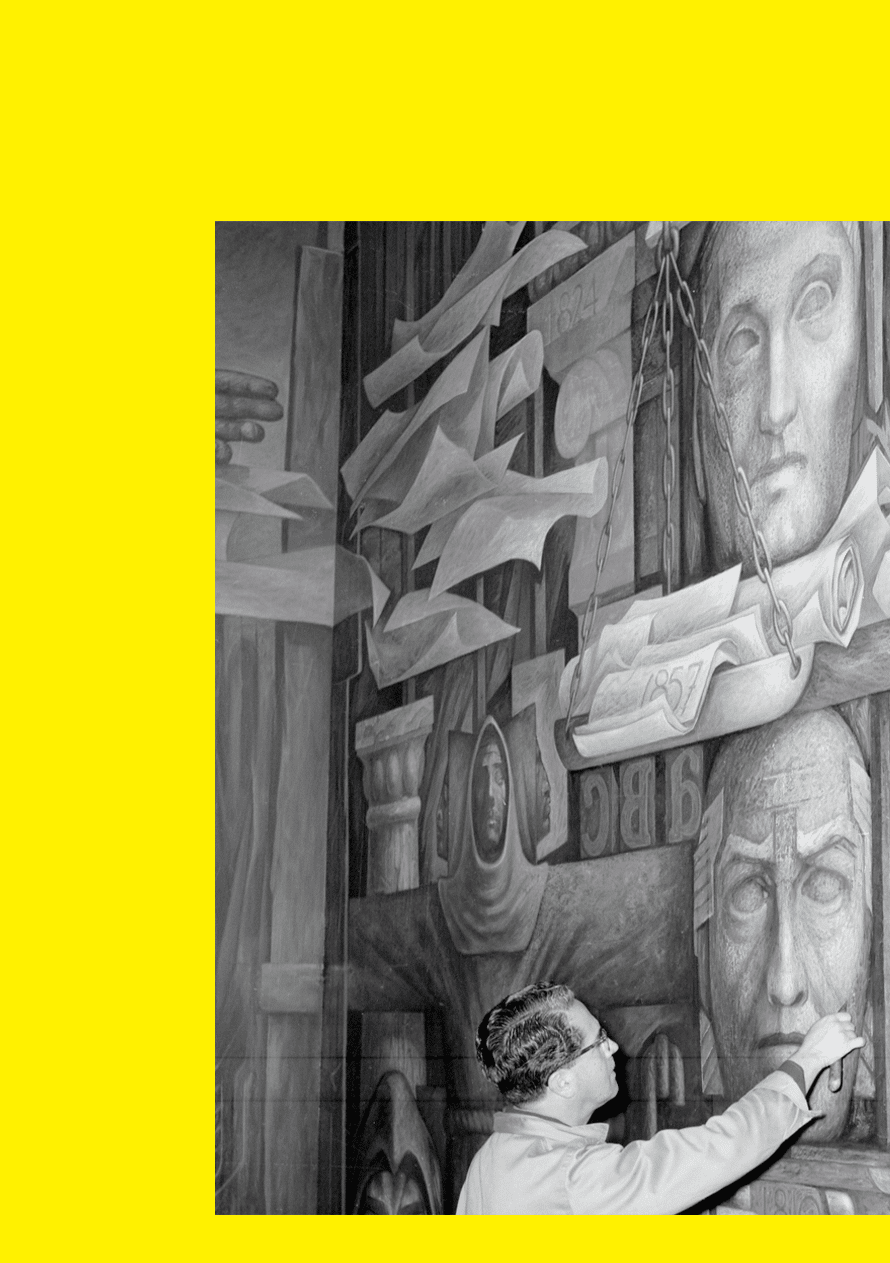

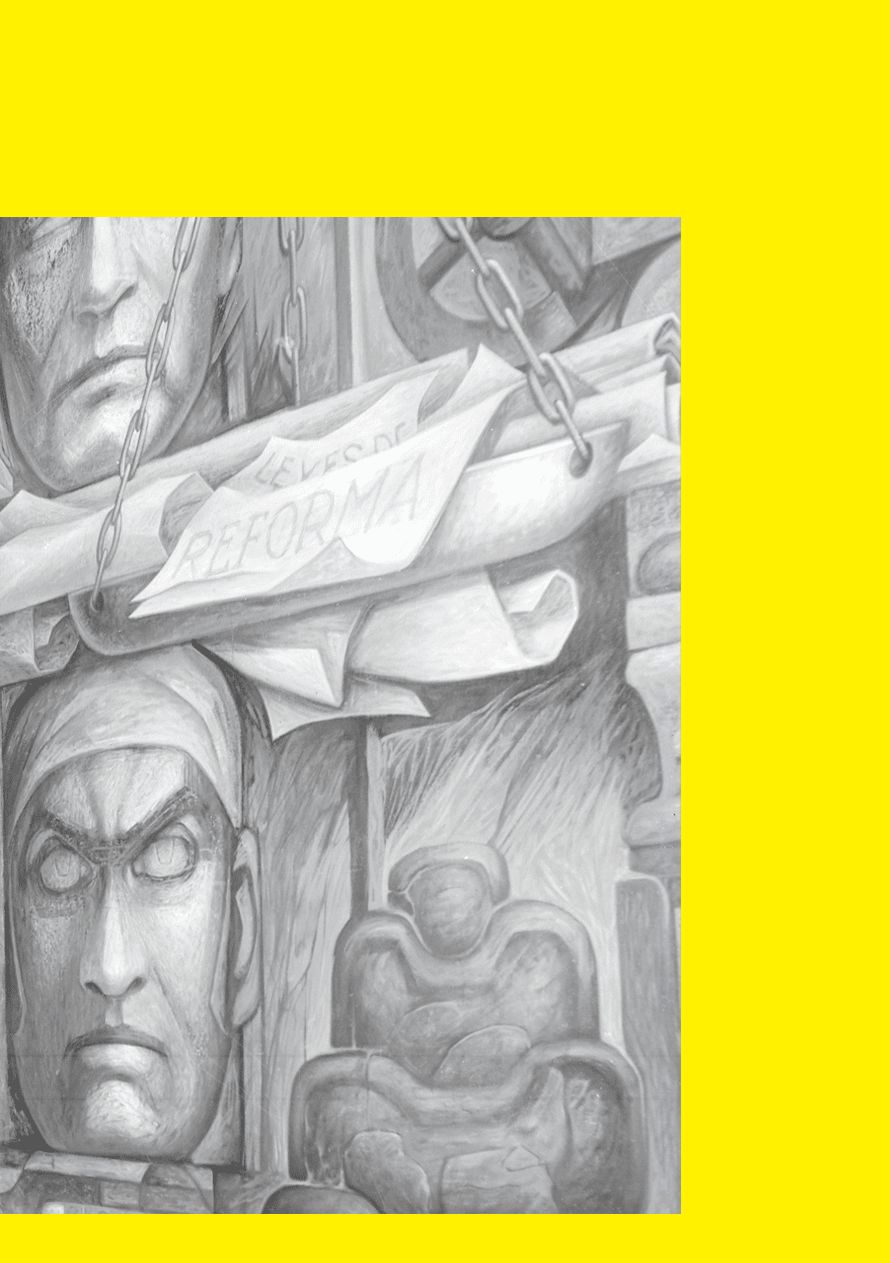

Muralism is a pictorial movement that emerged in the first decades of the 20th century to tell and document the history of the nation after revolutionary events. This aesthetic tradition became the hallmark of Mexican art and its influence extended to countries such as Cuba, Nicaragua, Argentina, Japan, Germany, Italy, Ireland, Spain and Iran, and others that experienced periods of oppression.

Far from European artistic trends, muralists sought to develop their own style, which would reflect national identity through revaluation of indigenous and mestizo roots, and vindicate the political and social function of art, as a resource for ideological propaganda and bring attention to social inequality.

By choosing walls as a medium of expression, Mexican muralists committed themselves to creating a permanent artistic corpus, of public access, made by the people for the people and, therefore, uncollectable.

Thus, artists such as David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, Gerardo Murillo “Dr. Atl”, Rufino Tamayo, Roberto Montenegro, Federico Cantú, Juan O’Gorman, Pablo O’Higgins and Ernesto Ríos Rocha, left an invaluable legacy through their works.

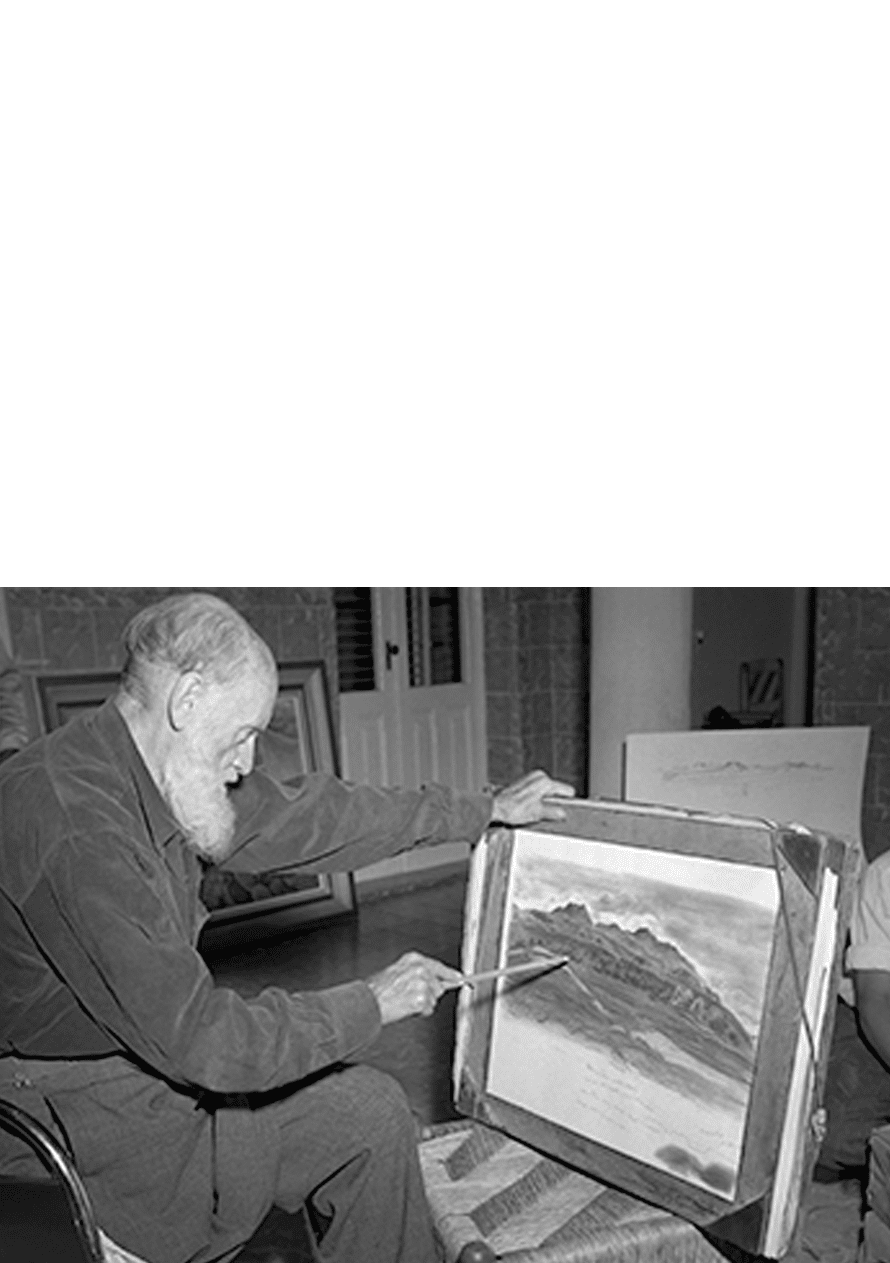

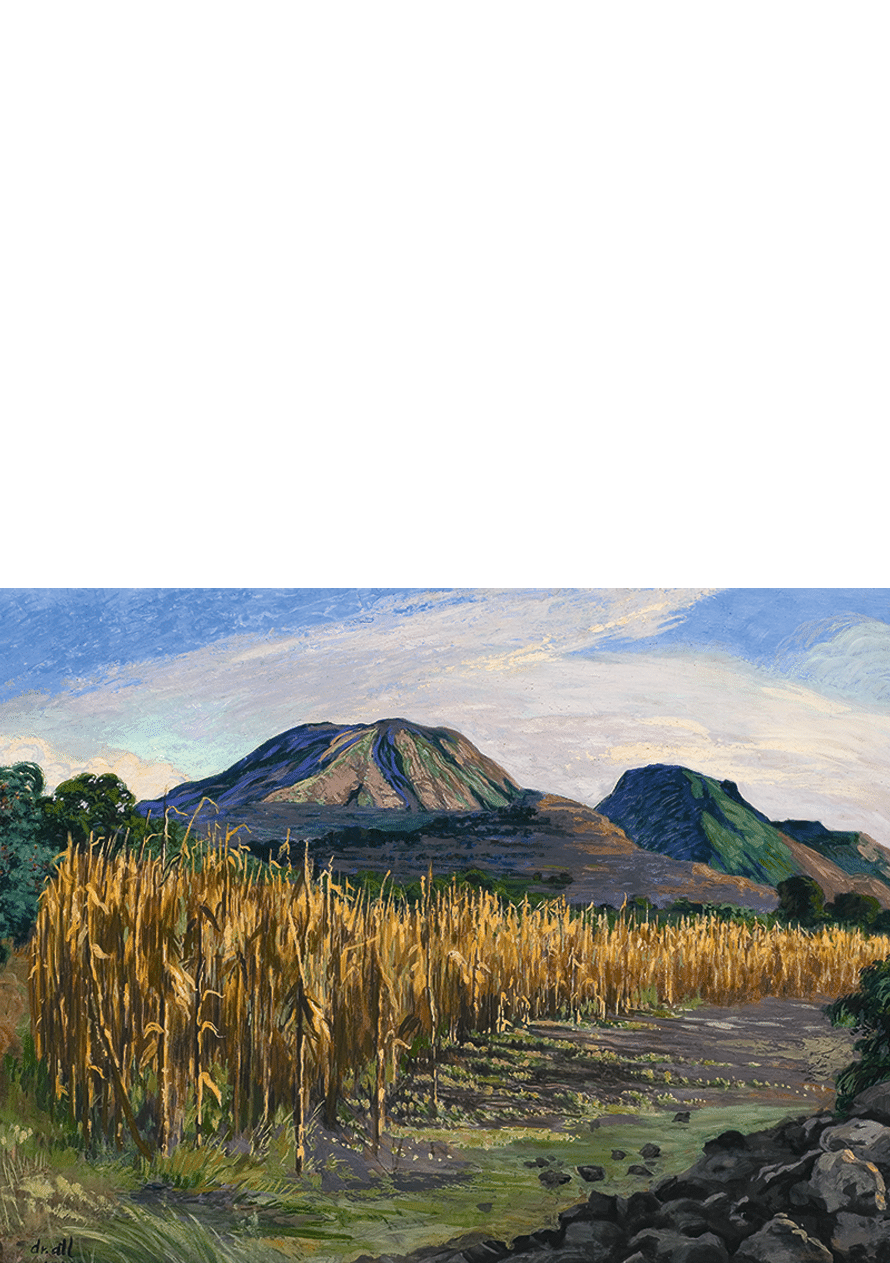

Gerardo Murillo Cornado (Guadalajara, Jalisco 1875–Mexico City 1964) changed his name in 1912, after facing a deadly storm while traveling in an ocean liner. In order to honor the of power of water, he called himself Atl, which means water in Nahuatl. He was a prominent landscaper and teacher of the mexican muralists.

Diego Rivera wrote: “He taught the youth insolence, wrote prose and poetry, and was an expert on volcanoes, botanist, miner, herbalist, astrologist, magician, anarchic materialist, totalitarian [...], he edited newspapers, organized red battalions, looted churches, invited beautiful ladies to tea at the sacristies, and gathered around him a group of young artists of greater value at that time”.35

His training covered studies in Philosophy at the University of Rome, Law at the Sorbonne in Paris, and was filled with Parisian artistic influences for his pictorial work. In the San Carlos Academy, in Mexico, he was known as the “agitator”, because he questioned traditional teaching methods emphasizing popular art. He developed a special technique called “Atl colors”, with which he made pigments based on resin, wax and oil, that gave them a unique consistency capable of painting even on rocks.