Tuberose is one of the best-known Mexican flowers worldwide for its intense aroma that it is capable of distilling for hours, its aroma so powerful that there was a time when it was considered a narcotic, used by women to intoxicate men.

The Aztecs called it omixochitl or “bone flower”, although it was also known as amole, since it was used as a soap substitute due to its antibacterial properties. It is a bulbous, herbaceous and perennial plant; its floral stem can grow over a meter and its flowers, clustered in a spike-shaped inflorescence, give off a scent that intensifies at nightfall.

In 1594 it was taken to Spain by Simón de Tovar, founder of the first botanical garden in Seville. Some time later, its cultivation spread throughout Holland, Italy and France, where it has stood out as a luxury perfume-making ingredient.

From the Nahuatl nixtli (ashes) and tamalli (dough), nixtamalization is the process of cooking maize grain with water and quicklime. This method makes maize nutrients easier to assimilate, it provides the distinctive color and flavor of our tortillas, and improves the nutritional value of maize for human consumption, adding valuable nutrients such as calcium, riboflavin and niacin. The transformation of maize into dough and then into tortillas —or some other of its innumerable forms— would not be possible without the texture and qualities that nixtamalization confers to it.

In Teotihuacán, casseroles were found to prepare nixtamal dating back to the 4th century of the Christian era, but knowledge of this process has been passed down from generation to generation, keeping it to this day. It is, without a doubt, the most important pre-Hispanic technological invention.

This shrub with a foliage that changes color during the winter —making it look like a flower— is a symbol of Christmas around the world, but especially in Mexico, where winter celebrations are inconceivable without it.

Since its origin, the poinsettia was an ornamental plant highly appreciated by the Aztecs. It occupied a special place in the gardens of Nezahualcóyotl and Moctezuma, where it was known as cuetlaxóchitl, which means fire-colored flower. It was also used for medicinal purposes to remove warts and verrucae, as well as to treat other skin conditions.

In the 17th century Franciscan monks named it “Christmas Eve flower” or “Easter flower”, because they used it to decorate the altars of the first temples, Christmas processions and the Holy Manger celebration.

Its biggest advocate was Joel R. Poinsett, the United States ambassador to Mexico, who sent it as a diplomatic present to various parts of the world at the beginning of the 19th century. Thanks to this it became one of the ten best-selling potted plants in Europe and the United States.

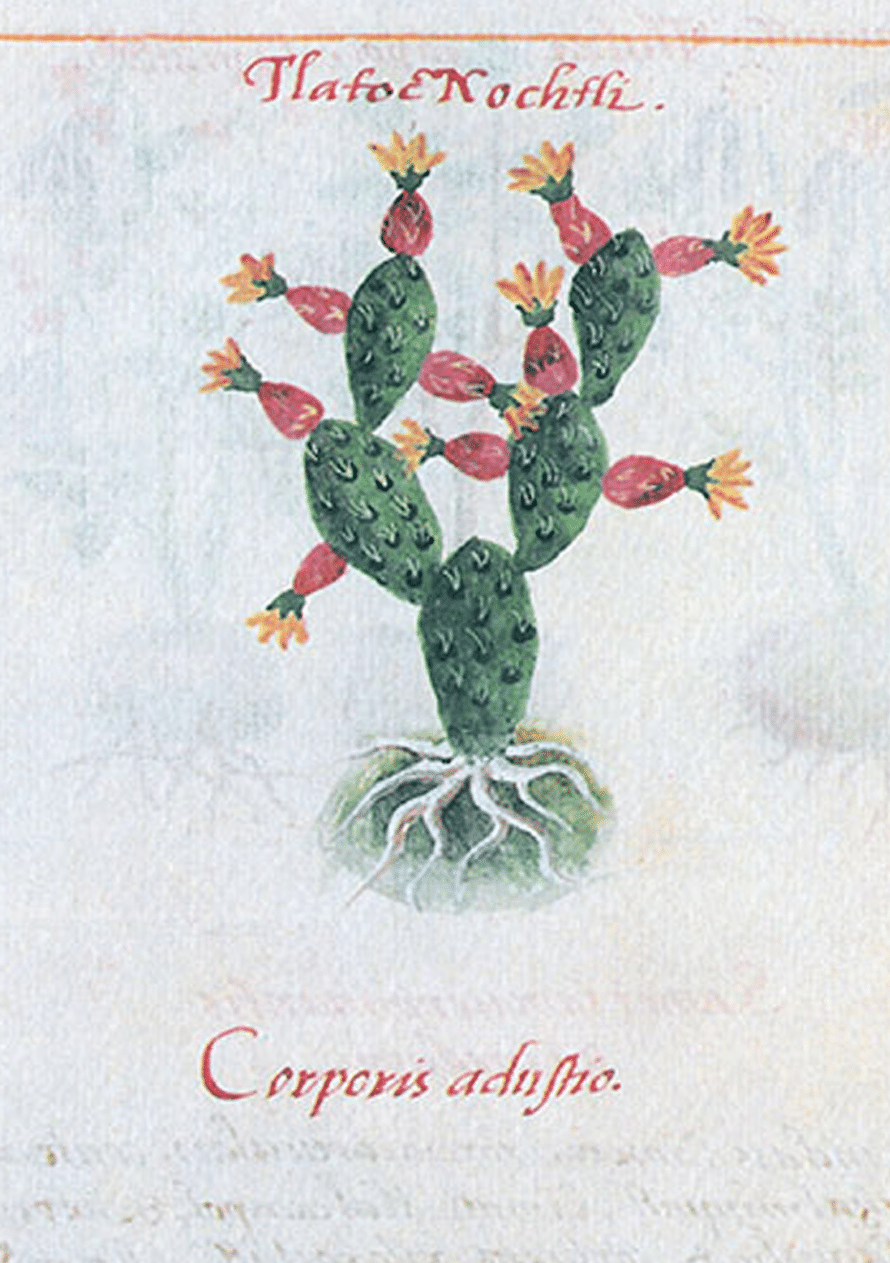

In the description of his discoveries in New Spain, Friar Bernardino de Sahagún speaks of a variety of “monstrous” trees, of which the edible leaves and fruits are part of the natives’ diet. He refers to nopalli, a plant of the cacti family, sacred to the Aztecs because they considered that its roots connected with the underworld, and the prickly pears, also called “sacred hearts”, with heaven.

This ancestral ingredient is an icon of our identity, an essential element of Mexican cuisine and landscape, immortalized in the national emblem by the myth of Mexico-Tenochtitlan's founding, where the Aztecs witnessed the eagle devouring the snake standing on a paddle cactus.

The name Enrique Norten (Mexico City, 1954) is one of the best-known in the contemporary field, synonymous with the movement of architectural renovation in Mexico and North America.

From his point of view, architecture must be bold and, above all, represent the historical moment in which it is inscribed, striking a balance between rough materials and technology. He discards the idea of buildings as art, although he considers that if a building has the ability to thrill or surprise without artifice, then it automatic-ally acquires that status.

With offices in Mexico City and New York, through his firm TEN Arquitectos —founded in 1986—, he has taken part in hundreds of projects of different scale and typology, including furniture design, individual family houses, residential, cultural and institutional buildings, as well as landscaping and master plans.

Among his most remarkable projects we can mention the Museo Amparo, in Puebla; the renovation of the New York Public Library; the Centro Cultural Álvaro Carrillo, in Oaxaca; and Habita hotels, in Mexico City and New York.

He has received many awards throughout his career. In 2005 he was presented with the Leonardo da Vinci World Award by the World Cultural Council; he was the first winner of the Mies van der Rohe Award for Latin American Architecture in 1998; and in 2011 he won the American Society of Registered Architects’ International Award.

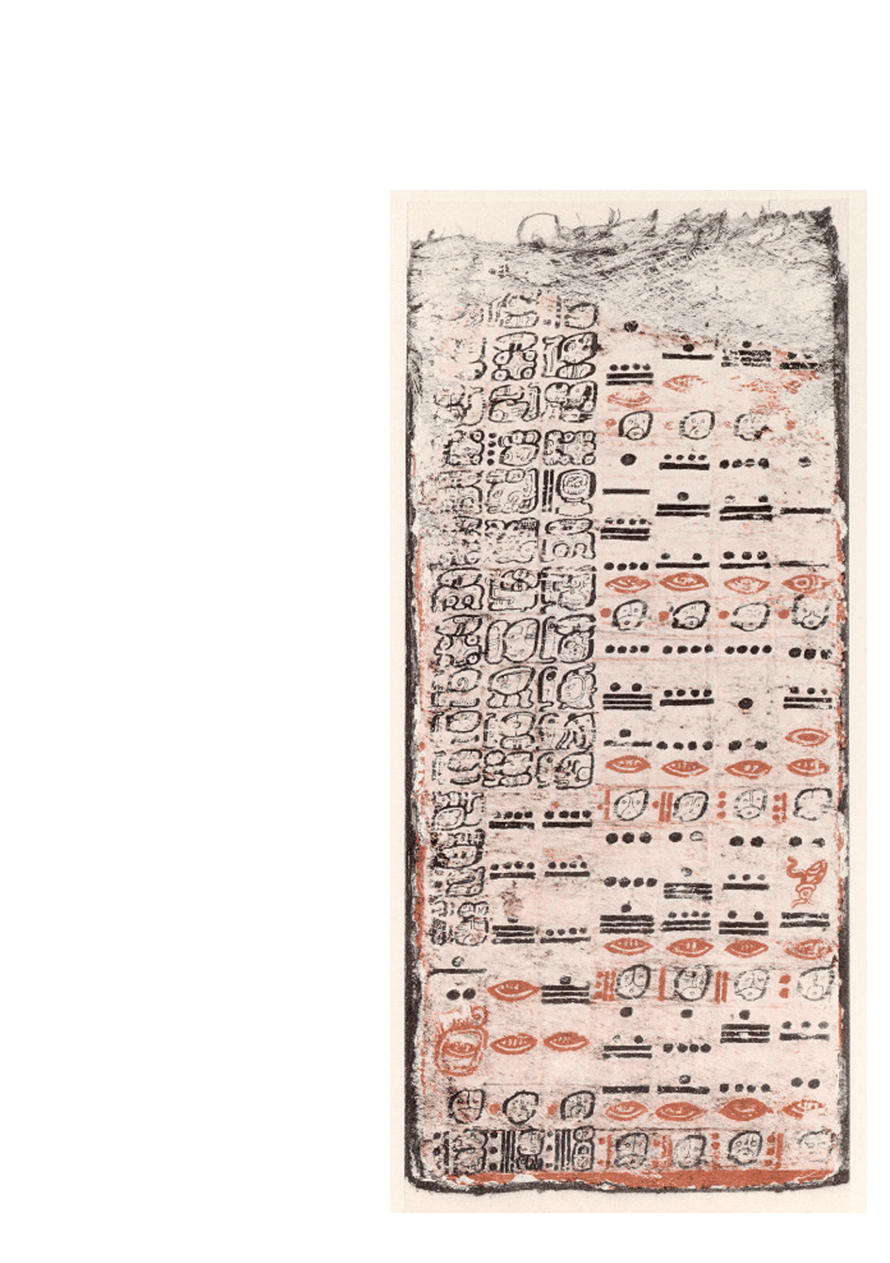

Zero is an abstraction to give value to emptiness that only two cultures in humanity achieved: the Hindu and the Maya. According to the researcher of Maya mathematics, Fernando Magaña, evidence shows that this discovery was made separately and that the Maya anticipated the Hindu by just over six hundred years.36

Hindu mathematician Brahmagupta, introduced the positional use of the zero sign, in the 6th century. This is why Hindu civilization is considered the cradle of the “evolved zero”, although in America the Maya had already done their share.

In Maya mathematics, based on the vigesimal system, the symbol of zero was represented with the drawing of a snail (or seed), a hand under a spiral or a face covered by a hand. These were the first documented uses of zero in our continent.

Unfortunately, much of the advanced Maya knowledge about astronomy, mathematics, architecture and other areas were lost when Spanish missionaries incinerated tons of manuscripts in an auto-da-fé. Fortunately, the teaching of the Maya mathematical system is being disseminated in Yucatán and outside Mexico in countries such as Italy or Spain, as a knowledge that not only explains a numerical system, but also develops a structure of thought that expands the analytical capacity of those who study it.