Much more than an actor, singer or public figure, Pedro Infante (Mazatlán, Sinaloa, 1917-Mérida, Yucatán, 1957) is celebrated as a national emblem, an icon of a golden age installed in the collective imaginary that for decades contributed to the construction of Mexicanness.

He recorded more than 300 songs and his face occupied the big screen in over 60 films, in which he stood out for his great charisma and the quality of his performances —sincere and touching—, which ultimately have made it difficult to separate the actor from his characters, turning him into the canon of the Mexican man: chatty, hardworking, ethical, chaste, good son, flirtatious, but loyal.

His tragic and premature death, gave him the quality of a myth that is still alive thanks to films such as the trilogy We the Poor (1948), You the Rich (1948) and Pepe el Toro (1953), Los tres García (1947), Full Speed Ahead (1951), El inocente (1956) and Tizoc (1957). He was nominated for an Ariel, won a Golden Globe and the Berlin International Film Festival’s Silver Bear for Best Actor.

With over 549 species, Mexico is a world leader in edible insects. Entomophagy is the legacy of ancient Mexicans who consumed very little meat in their diet, since insects represented their main source of protein.

In the Florentine Codex, 96 species of insects are described; the favorites in the pre-Hispanic diet were the honeypot ants (necuázcatl), ant eggs (azcatlmolli), maguey worms (meoculli) and grasshoppers (chapolin).

Currently, mosquitoes and arthropods are still part of the diet of Mexicans: scorpions, stink bugs, larvae, ahuautles (hemipteran insect eggs), leaf-cutter ants, cuchamá worms, crickets, flies, termites... And many more are the perfect appetizer, seasoned with lime juice, chili, garlic and onion. In addition to their high protein content they are rich in iron and other nutrients, making their consumption very healthy.

Mexican musical instruments are those of indigenous or mestizo origin, either completely original or modified foreign instruments that evolved in our country to produce the peculiar notes of traditional Mexican music.

An example of this are mariachi’s distinctive instruments, such as the Mexican vihuela, a relative of the Spanish vihuela made of mahogany and known for its bulging shape; or the guitarrón, which replaces the double bass. Both instruments were invented in Cocula, Jalisco.

A distinguished member among the list of Mexican musical engineering is undoubtedly the requinto guitar, the essential sound in trio music. Popular all over the world, this small high-pitched guitar was invented in 1943 by Alfredo Gil, member of Los Panchos trio. A professional lute player was entrusted to carry out the order of the interpreter and composer, who was looking for an instrument of similar size to the Colombian tiple, but with more frets and the possibility of a more acute tuning, as well as an alteration that would make playing the notes easier.

Other instruments such as the jaranas —from La Huasteca and from Veracruz—, the Mexican psaltery, the chapareque, the Aztec flute, the pre-Hispanic drums, the Aztec jingles and the marimbula, are just some of the members of the immeasurable Mexican sonorous universe.

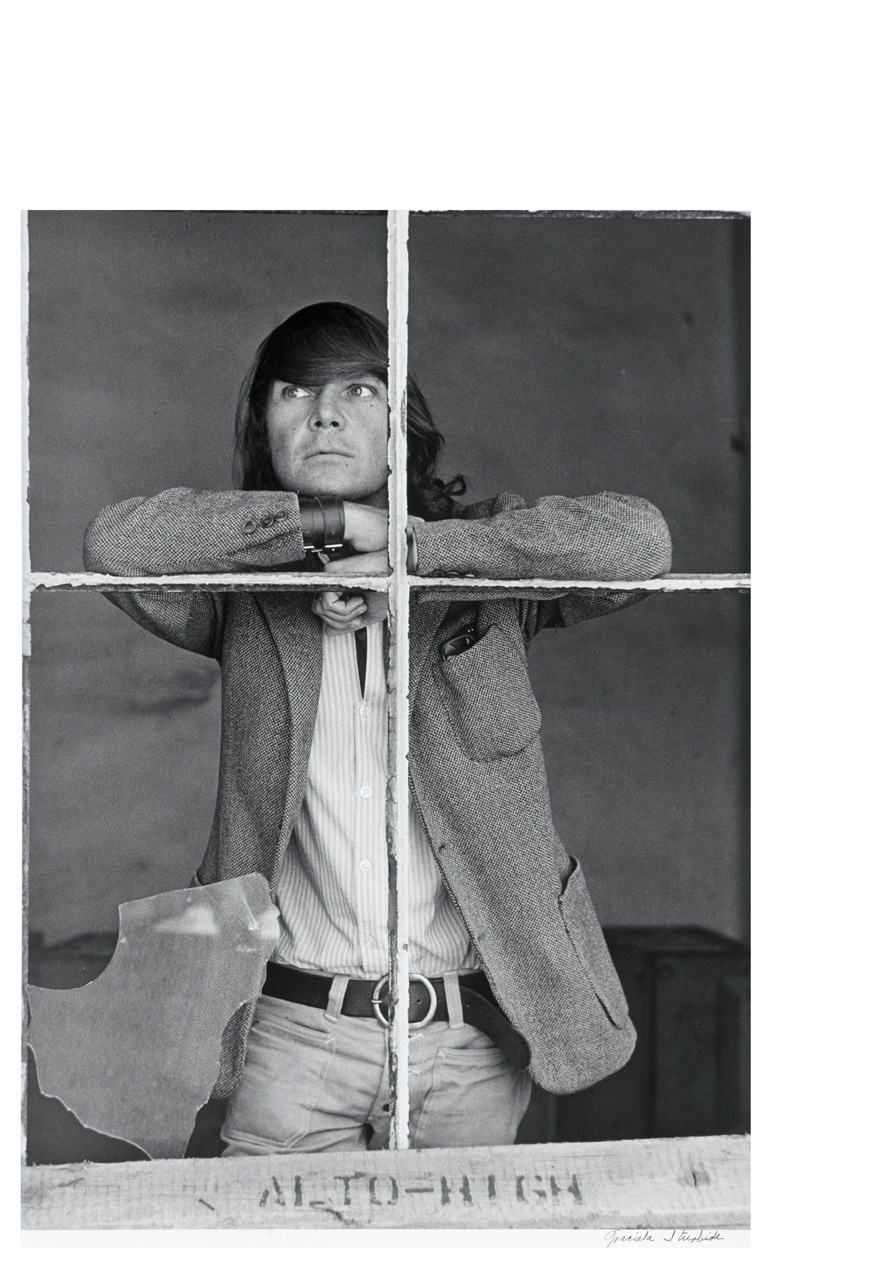

“A camera is an excuse to get to know yourself and the world”, says Graciela Iturbide (Mexico City, 1942), who in 2008 won the Hasselblad Award in Sweden, considered the Nobel Prize in photography.

In 1969 she entered the UNAM’s University Center for Film Studies, hoping to become a filmmaker. However, along her path she came across Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s photography chair, which she attended, soon becoming his assistant. For just over a year she accompanied the legendary photographer in his travels around the country and developed a form of observation that soon specialized in portraying indigenous communities of Mexico.

Graciela Iturbide has known how to eternalize reality without impostures; she allows life to happen in front of her camera. Her favorite photo is Mujer ángel (1979), a gift from the Sonora Desert, in which an unknown Seri woman heads quickly towards the scrubland holding a tape recorder in her hand.

She is the author of several books, among which stand out: Those Who Live in the Sand (1981) and Juchitán de las mujeres (1989). She has been invited to work in Germany, India, Madagascar, Hungary, Cuba, France and the United States.

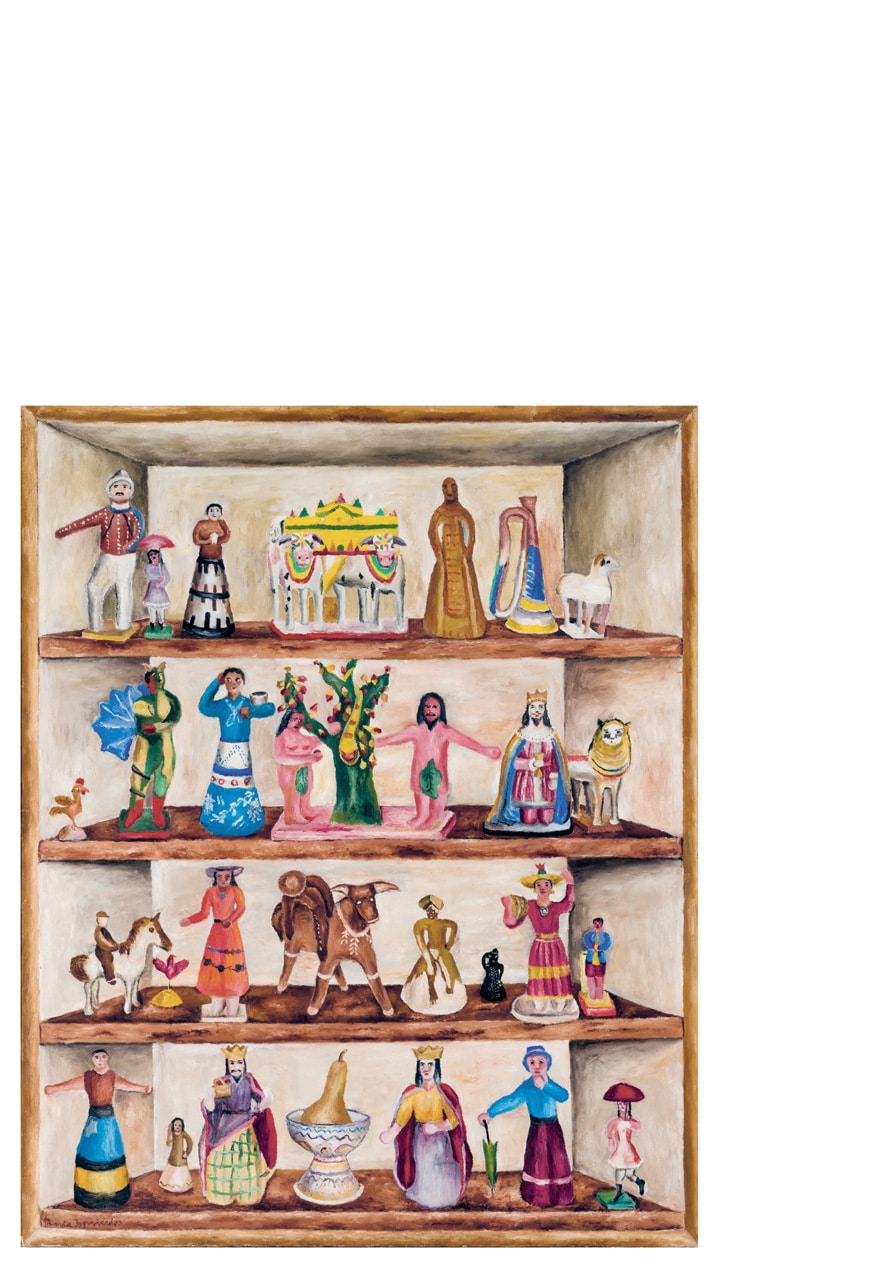

The day the real history of Mexican painting of this century is written, the name of María Izquierdo will be a small but powerful center of magnetic radiation.

Octavio Paz

Born in San Juan de los Lagos, Jalisco, María Izquierdo (1902-1955) was the first Mexican painter to exhibit her work in the United States, first at the Art Center in New York, in 1930, and later at the Museum of Modern Art in the same city, in the exhibition Mexican Arts, achieved against all odds and avoiding the prevail-ing machismo of the time.

“It is a crime to be a woman and have talent”, she said after the disappointment she experienced in 1945 when she was hired to paint a 200 square meter mural and was later dismissed from the project when some important muralists of the time intervened, opposing that the commission had been granted to a woman.

But sabotage did not stop her, she became actively involved in the defense of women’s rights, she painted monumental murals, such as La música and La tragedia (1946), and continued painting even after being paralyzed by hemiplegia on the right side of her body in 1948. Her work, full of color and dream worlds, sought to be “an open window to the human imagination” and has been declared cul- tural heritage of the nation.