Tacos are the top culinary ambassadors of Mexico in the world. They are prepared with maize or wheat flour tortilla, folded or rolled, stuffed with any type of stew or meat.

Their origin was a diversion of the use of the tortilla, which was originally used as a spoon or edible plate. The natives called it tlatoalli, which means “tortilla with filling”.

It is the most eaten antojito in our country, with a perennial presence at home tables, restaurants, diners, markets and street stalls. Their name almost always refers to the way they are prepared or their specialty. Among the best known are the dorados —fried in oil— soft ones and steamed tacos; there are even tacos with no filling, which are just a simple folded or rolled tortilla, served naturally or fried, alone or with chili sauce.

Tacos al pastor are also known as trompo tacos, they are filled with pork meat, marinated in a sauce of dried chilies and annatto, which is skewered on a sword, resembling the shape of a spinning top crowned with a pineapple, which the taquero turns manually while grilling. They are served with chopped onion and coriander, lime juice and chili sauce.

These famous tacos, catalogued as the best dish in the world by Taste Atlas website, appeared in the 1920s when a group of Lebanese people merged the shawarma technique —prepared with marinated lamb meat and cooked on a skewer— with local ingredients.

Of the great variety of dishes made with nixtamal dough, the most important are, undoubtedly, tortillas and tamales —originally called tamalli, which means “wrapped” in Nahuatl.

The dough, mixed with a filling or simply chili sauce with meat and vegetables or beans, is carefully wrapped in maize or banana leaves, and then left to steam.

In ancient Mexico, tortillas were the everyday food, while tamales were kept for large festive banquets. Their origin is linked to the domestication of maize. Evidence has been found, at the archaeological site of Teotihuacán, that suggests their use between the years 250 B. C. and

750 A. D.

Nowadays, tamales are no longer a dish for special occasions and have become a part of daily life of Mexicans, especially in Mexico City, where tamale in a bread roll is essential nourishment. Tamales also continue to be protagonists of celebrations such as the Day of the Dead, La Candelaria and Christmas in northern Mexico.

There are over 500 types of tamales: from chipilín to casserole tamale, chanchamitos, piltamales, vaporcitos and zacahuiles, among many others.

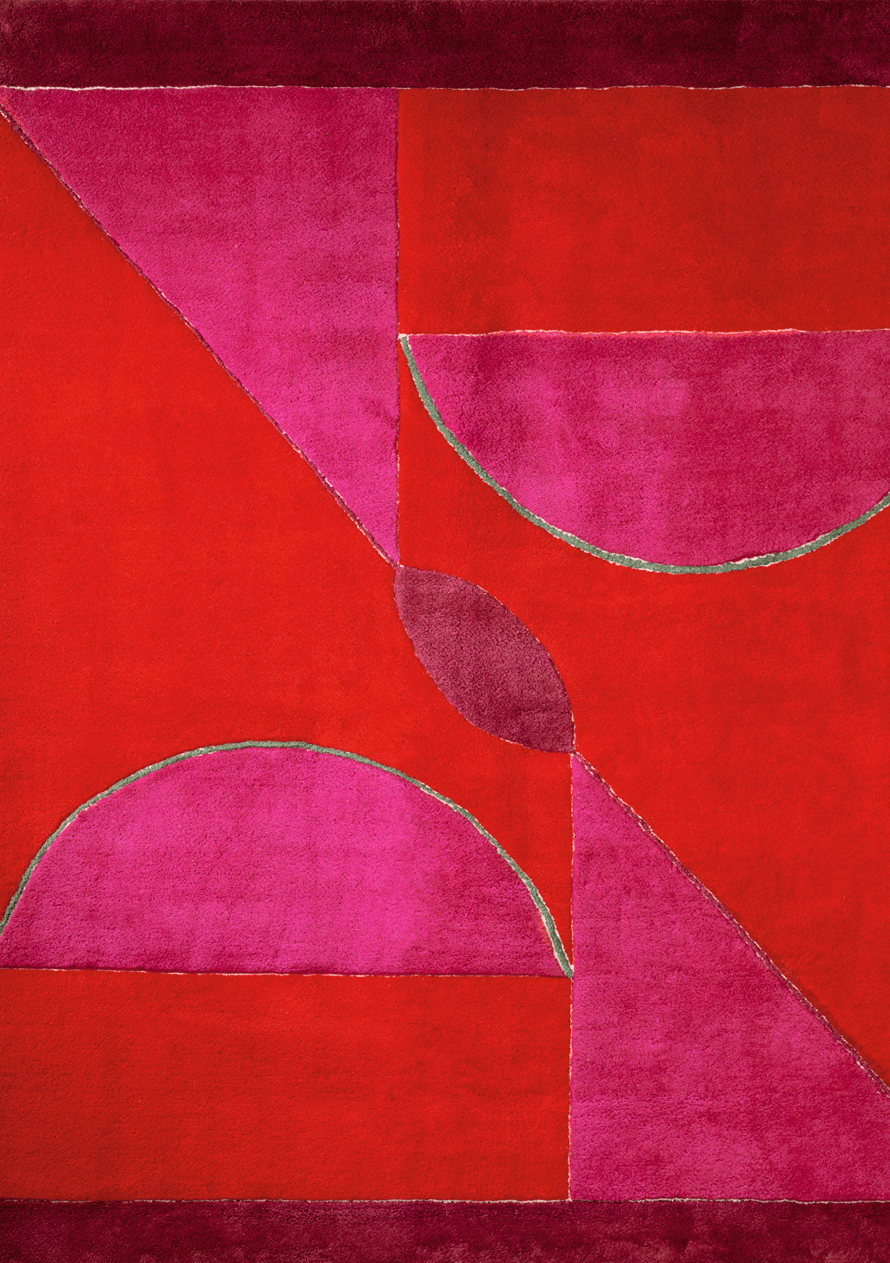

Originally from Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca, Rufino Tamayo (1899–1991) is one of the great Latin American muralists, known for his rebellious stance, as he kept his distance from some of the precepts of the nationalist movement in search of his own interpretation of Mexicanism.

“My sentiment is Mexican, my color is Mexican, my figures are Mexican —he stated— but my concept is a mixture [...]. I am Mexican, nourished by the tradition of my land, but at the same time I receive from the world and give to the world as much as I can: this is my creed as an international Mexican”.53 Instead of demonizing the influence of European trends, Tamayo embraced them and combined them with his profound knowledge of pre-Columbian art and his indigenous roots. Unlike Rivera, Siqueiros and Orozco, he chose free painting, without historicism or political proclaim, which gave his work a universal character.

His most iconic murals are Homenaje a la raza (1952) and México de hoy (1953). Over time he changed murals for canvases and easel; he was a forerunner of the mixograph technique and did 600 oil paintings, 400 portraits and 21 murals. The Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Internacional Rufino Tamayo in Mexico City is one of the most modern art centers in the world, which has promoted the work of hundreds of international artists.

Inventor and entrepreneur Manuel Gutiérrez Novelo is the holder of over 45 patents around the world, related to the development of 3D technologies. The path that this native of Guadalajara has traveled to become known as the “technological ambassador of Mexico” be-gan when his grandparents gave him a toy called View-Master, which showed photograph slides in 3D.

The boy wondered why there was no system that could emulate this effect in his favorite television shows and since nobody invented it, he set himself to achieve it. Decades later, he designed a method to encode three-dimensional stereoscopic images used in all home 3D Blu-ray players.

In 1999, unable to find support from Mexican institutions, he obtained an investor visa in the United States and soon captured the interest of NASA, the Pentagon, Walt Disney and DreamWorks, companies with which he developed devices such as the head-mounted display or multilens cameras for 3D immersive experiences and virtual reality.

Gutiérrez Novelo is convinced that in our country there is enough talent to be at the forefront in the development of new technologies; therefore, he has undertaken a series of collaborations and efforts so that young inventors do not have to emigrate to fulfill their dreams. His work has been essential in highlighting Mexico’s presence at the International Consumer Electronics Show (CES).

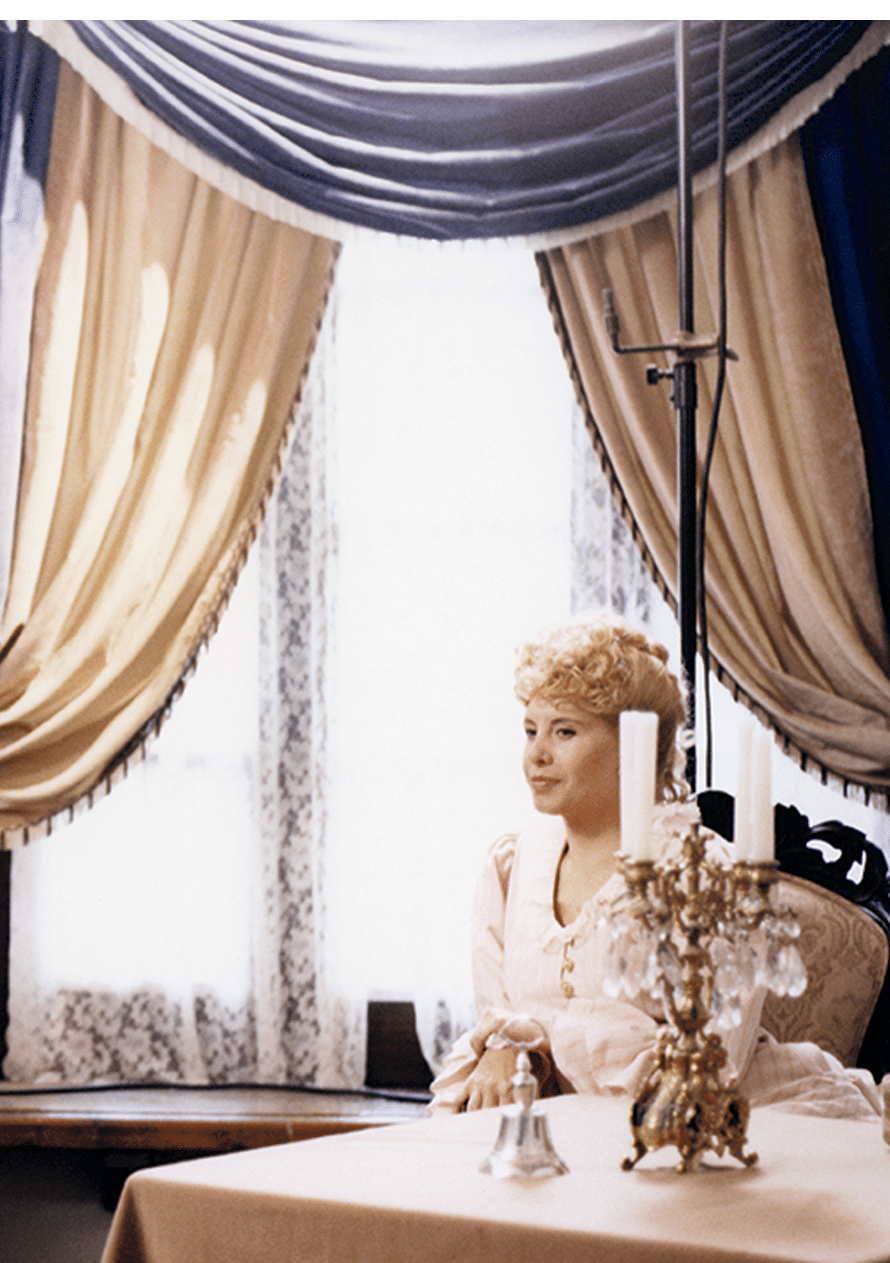

The origin of this television genre dates back to the French feuilleton serial stories of the 19th century, which resulted in romantic comedy and later found voice and musical background in the radio soap operas. When the use of television became popular, the stories searched for a space within the small screen.

The first prototype of a weekly serial plot on television, with the romantic halo of European feuilletons, was created in Cuba in 1951. That same year, “Ángeles de la calle” was released in Mexico. The format we know today did not begin until 1958, the year in which “Senda prohibida” was broadcasted in our country.

The global reach of these serials took place in 1978, when “Los ricos también lloran” was taken to Russia, China, the United States and the Middle East. It was so successful that its protagonist, Verónica Castro, was appointed Ambassador of Peace in Russia, and soap operas became the most exported product by media company Televisa, forefather of the genre.

The melodramas’ route garnered audiences in the most unexpected places and their protagonists —such as Victoria Ruffo, Edith González and Thalía— were received as heroines both in Turkey and Uzbekistan, the Philippines, Armenia and Indonesia. The impact of soap operas has been the subject of countless analyzes and criticisms, but it has also been explored as a teaching resource.

In 1984, Miguel Sabido, creator of the educational soap opera, received an invitation from Indira Gandhi to develop in India a plot that promoted harmony between castes and a critique of arranged marriages in this country. Thanks to UNESCO, these types of productions known as the “Sabido model” enjoyed great success in countries such as Ethiopia, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Malawi, Burkina-Faso, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sudan and Swaziland, providing information on topics such as family planning and gender equity.

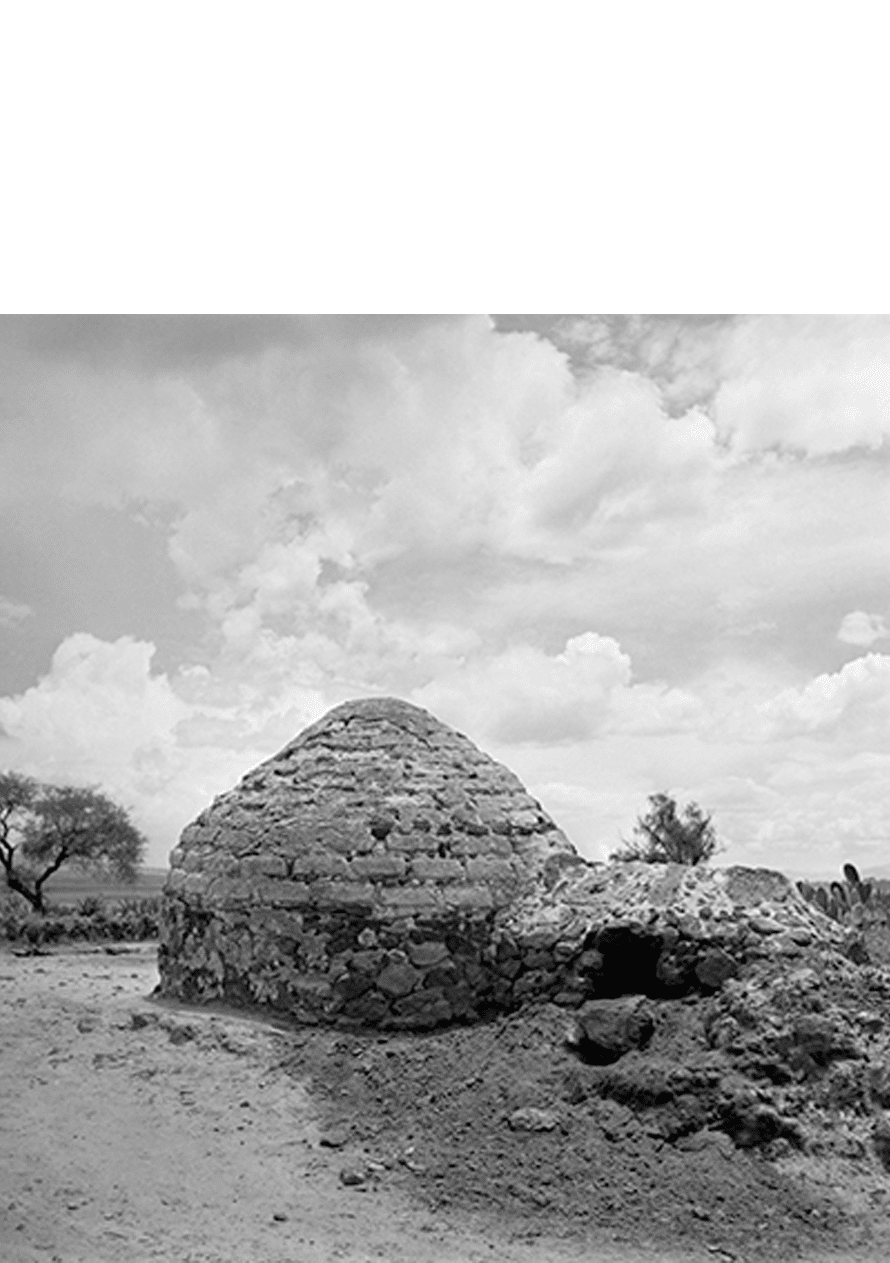

The word temazcal comes from the Nahuatl temazcalli, which means “bath house”. It is a powerful pre-Hispanic steam bath, based on hot volcanic stones and healing plants, which is used for therapeutic, hygienic and ritual purposes.

According to Aztec cosmogony, the temazcal tradition symbolizes a reconnection with the mother’s womb, a place for cleansing and rebirth, protected by Temazcaltoci —mother of the gods, grandmother of Earth— so it not only purifies the body but also the soul. Despite the efforts of the Spanish conquerors to eradicate it, the temazcal practice is still in force and is attracting more and more adepts.

Benefits of this millenary technique include ac-celeration of the healing process, especially injuries, broken bones, contusions and skin problems, as it stimulates skin renewal. It also helps fight the flu, bronchitis, asthma, sinusitis and other diseases, in combination with medicinal plants; also, traditional midwives use it to prevent pregnancy discomfort, and during delivery and postpartum care.

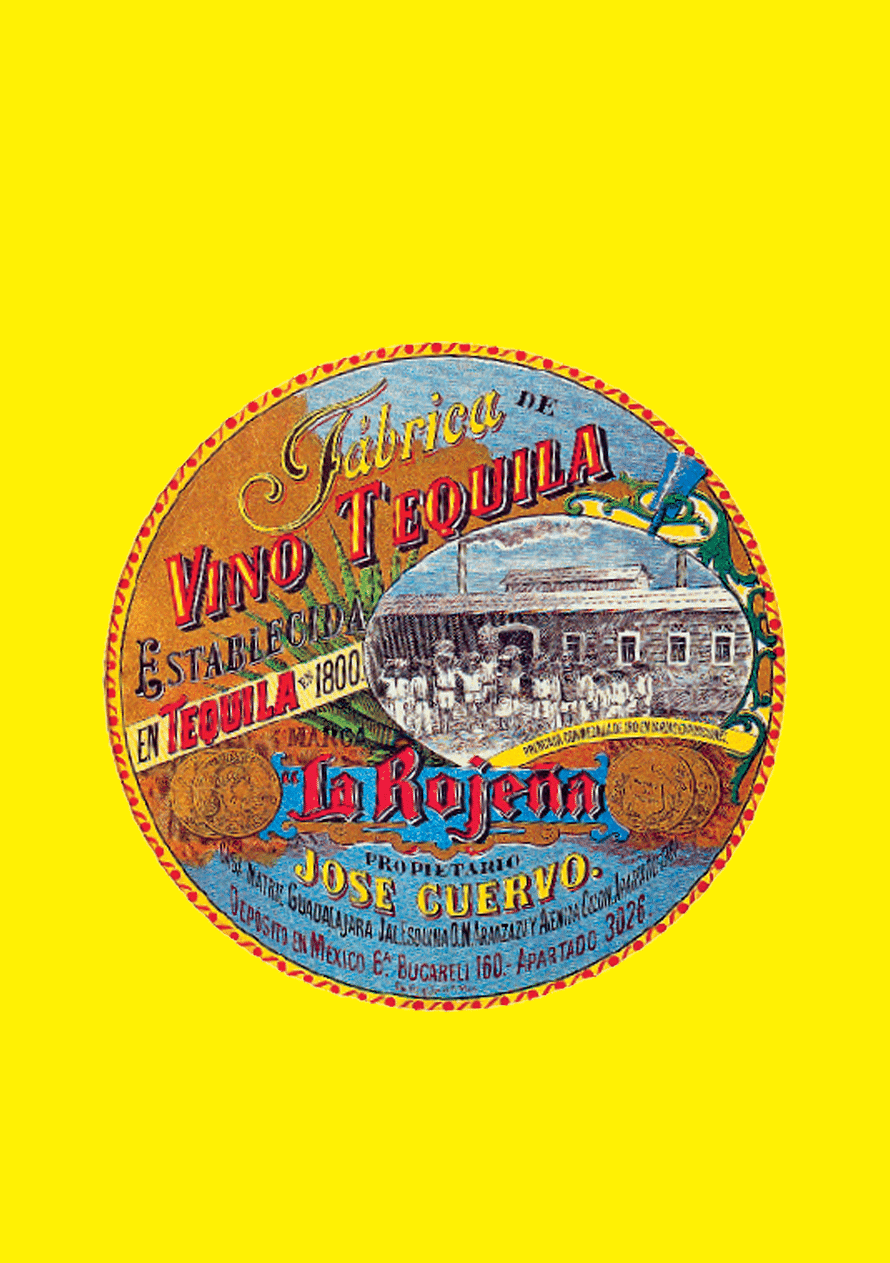

Tequila is the best-known agave distillate in the world. It is obtained exclusively from the blue agave tequilana variety —tequilana Weber— that grows mainly in the town of Tequila, Jalisco.

It has been consumed since colonial times and at the end of the 19th century it began to be exported under the name vino mezcal de Tequila. Later, by distilling this mezcal for a second time, it began to be marketed as we currently know it.

Revolutionary times gave tequila a final boost. Both national rebirth and film, one of its main promoters, took to the farthest corners of the world the image of happy and resolute Mexican riders, who both cured their sorrows and celebrated their joys by drinking tequila.

This spirit is popularly taken in a shot glass known as tequilero or caballito. It can be drunk straight or partnered with sangrita, and it is used in cocktails such as paloma, margarita, charro negro, vampiro and cucaracha.

The agave landscape of Tequila, Jalisco, from which this iconic drink derives its designation of origin, has been declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, in recognition of its beauty and cultural importance.

Mexican textile tradition is not only a lively and constantly changing artisanal practice, but it also represents a language through which our ancestral cultures show their identity and immortalize their customs and cosmogony.

In all indigenous communities of the country there are textile artists, weavers and embroiderers who have protected techniques and symbolisms. As has been stated by the Museum of Popular Art these “miraculous hands turn needs and fears into spirit, popular works of art arising from the biodiversity that comprises their natural habitat”.

The wealth of this heritage begins with the pre-paration and dyeing of fibers and threads with natural pigments, and it culminates with designs and the execution.

In Oaxaca this wisdom is preserved in the hands of the Mazatec, the Chinanteco, the Mixes and the Zapotec peoples. The latter, inhabitants of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, work one of the most well-known embroideries in the world over dark velvet garments: large colorful flowers and a border of pleated silk on the edge of the skirt, known as the Tehuana costume. Other communities are the Maya, in Yucatán; the Purepecha and Otomi, in Michoacán; the Teneek (or Huastec), in San Luis Potosí; the Totonac, in Veracruz; the Mazahua, in the State of Mexico; the Amuzgo, in Guerrero; the Tzotzil, Tzeltal and Zoque, in Chiapas; the Rarámuri-Tarahumara, in Chihuahua; and the Huichol-Wixarikari, in Nayarit.

The beauty of the artisanal textile work of these cultures is so great that, unfortunately, there have been multiple cases in which international designers and companies simply appropriate these designs and market them without acknowledging their cultural importance and the sometimes sacred character of this iconography.

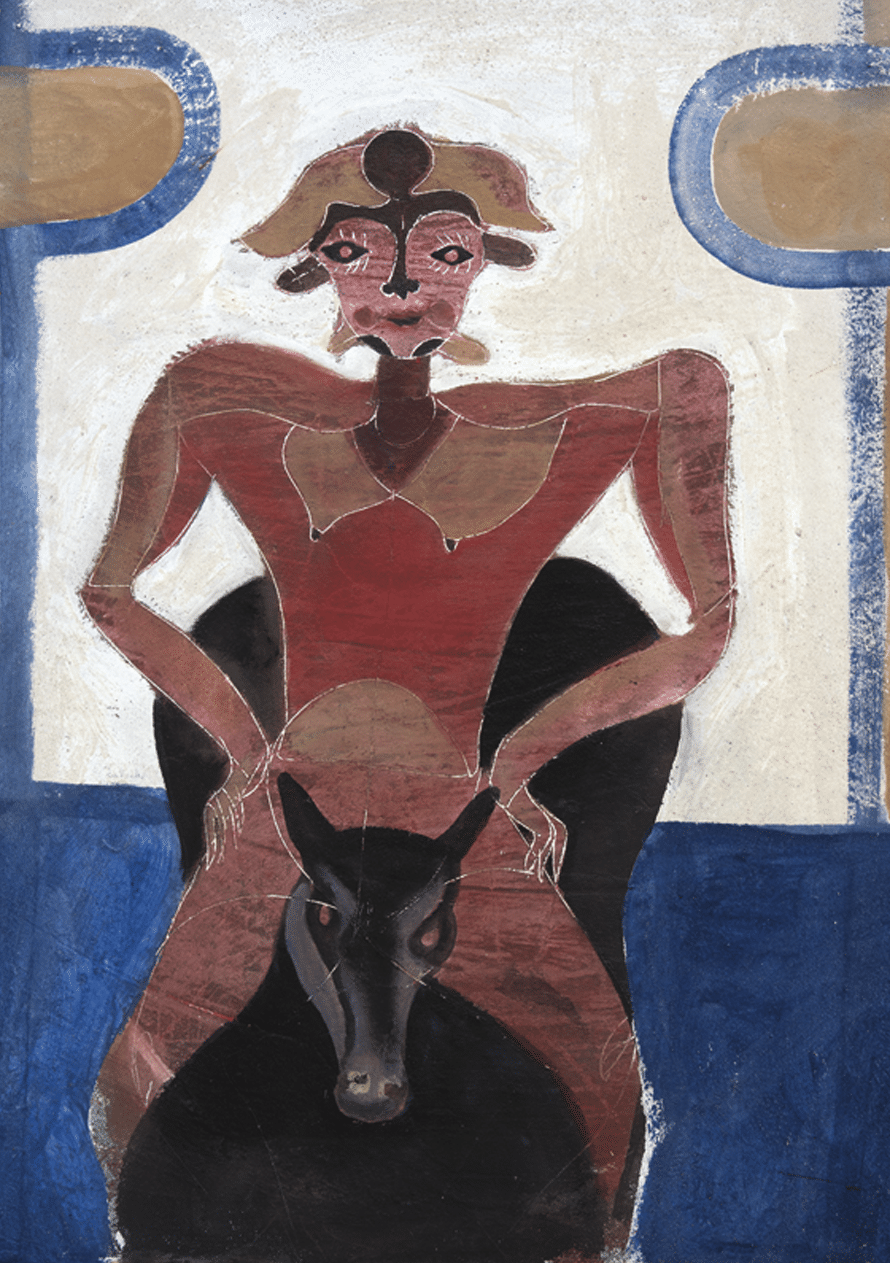

Art critic María Minera states that Francisco Toledo (Juchitán, Oaxaca, 1940-Oaxaca de Juárez, Oaxaca, 2019) is “the artist who opened the doors of the old universe of myths, and knew how to transfer them to the present […], a tireless creator […] of an ample body of work that owns —and owned since its inception— an ability for invention so unusual that without a doubt it is among the most interesting and irreplaceable research of Mexican art of all time”.

In 1959 he presented his first exhibition at Antonio Souza’s gallery; subsequently, he exhibited his work in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Belgium, Spain, France, Japan, Sweden, United States and other countries.

Endowed with unlimited creative vigor, he was not only an exceptional artist who cultivated every imaginable means of plastic, traditional and graphic arts —a master skilled in all techniques— he was also a true defender of heritage and memory, promoting and disseminating the culture and arts of his home state.

To this end he founded Ediciones Toledo, the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Oaxaca and the Centro Fotográfico Álvarez Bravo, among others. He also headed environmental projects to protect areas such as Monte Albán and the Papaloapan River, for which he received awards including the Federico Sescosse Award granted by UNESCO’s advisory body, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (2003).

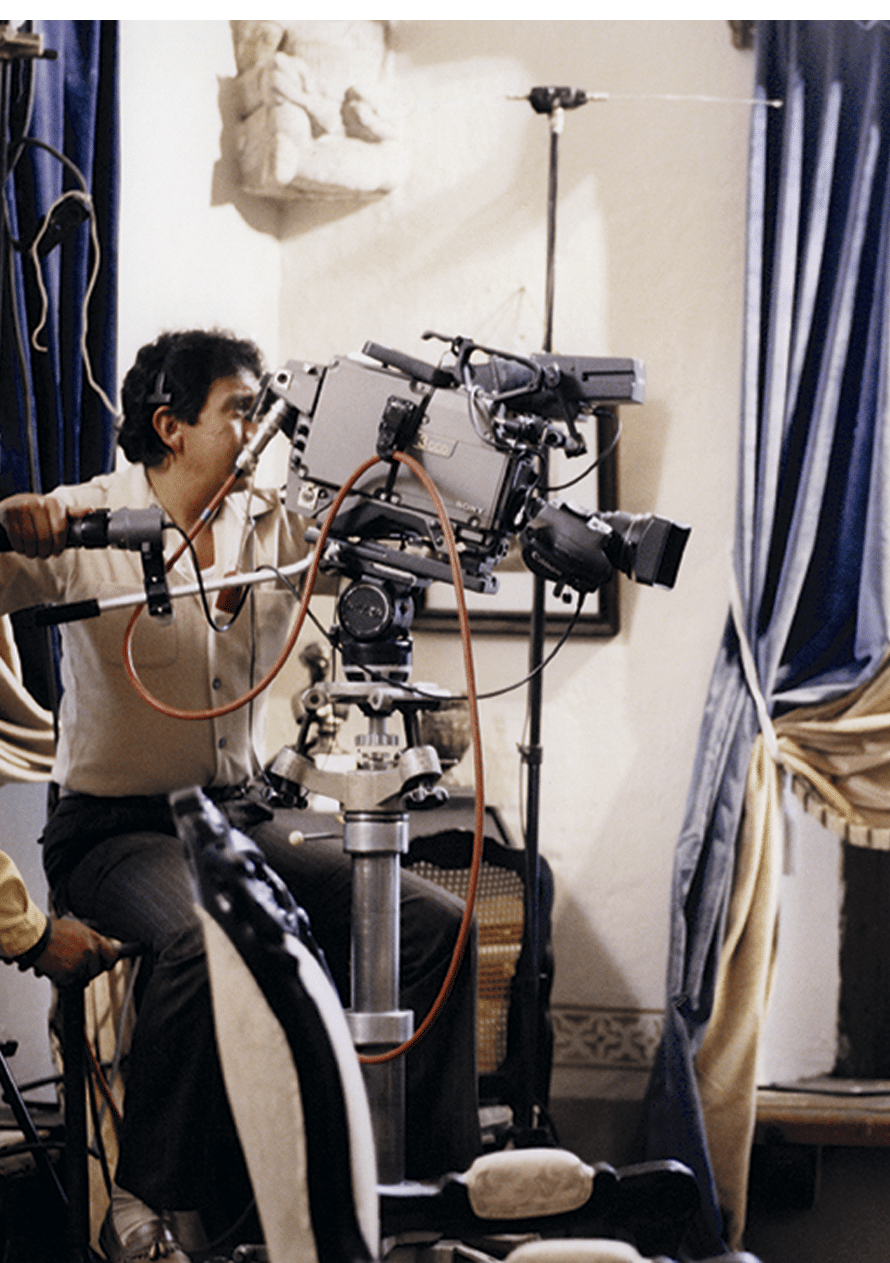

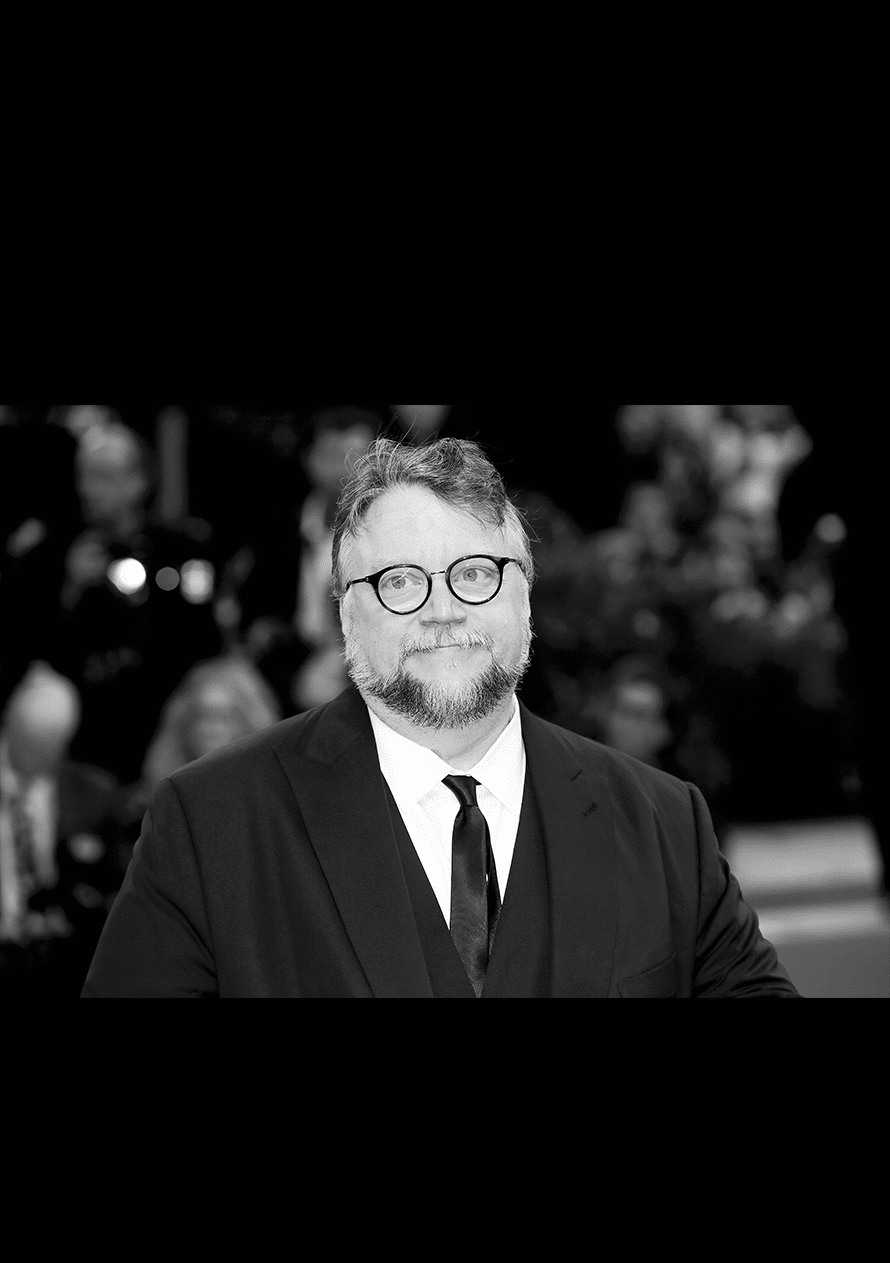

During a press conference in 2018, after receiving the Golden Globe for Best Director in his movie The Shape of Water, Guillermo del Toro was asked how he was able to see the dark side of human nature and at the same time be a cheerful and loving person. “Because I am Mexican”, he replied. “No one loves life more than we do, because we are so conscious about death”.

With his debut film, Cronos (1993), Del Toro showed that there was much more in Mexico than a fatalistic gaze in films and he opened a window to the stories of endearing monsters and fantastic worlds that have marked his career. The Devil’s Backbone (2001), Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) and Hellboy (2004), are just a few of the dozens of films that have established him as a reference of current cinema.

But in addition to his many awards, “Totoro-san” —the eternal child who once made a pact with his monsters to redeem them— has also become one of the most beloved Mexicans. A titan willing to support all kinds of causes: from granting scholarships, to helping the children of the Mexican Mathematics Society team to attend the Mathematical Olympiad in South Africa and winning.He is convinced that “every time we show Mexican exports, things like science, art and culture, it generates an important discourse in the world and helps us remember where we are from”.54

The transformation of maize into tortilla has been, for centuries, a main element in the diet of Mexicans. It can be described as a thin circle made of maize dough, traditionally cooked on a hotplate. Its invention is attributed to the Olmec culture, the first people that cultivated fully domesticated maize on the southern Gulf of Mexico coast.

In the General History of the Things of New Spain, Friar Bernardino de Sahagún dedicated several pages to describe tortillas: “The tortillas the lords ate every day are called totonqui tlaxcalli tlacuelpacholli, meaning ‘folded white and hot tortillas’ […]; they also ate other tortillas every day called veitlaxcalli, meaning ‘large tortillas’, these are very thin and wide and very smooth”, among many others.55

Tortillas are eaten hot and are used as a plate, cutlery and wrap. Whether made by hand, using homemade tortilla makers or made in industrialized machines, they are the raw material for preparing tacos, quesadillas, enchiladas, enmoladas, entomatadas, flautas, tostadas, tortilla chips, chilaquiles, soups and an endless number of dishes.

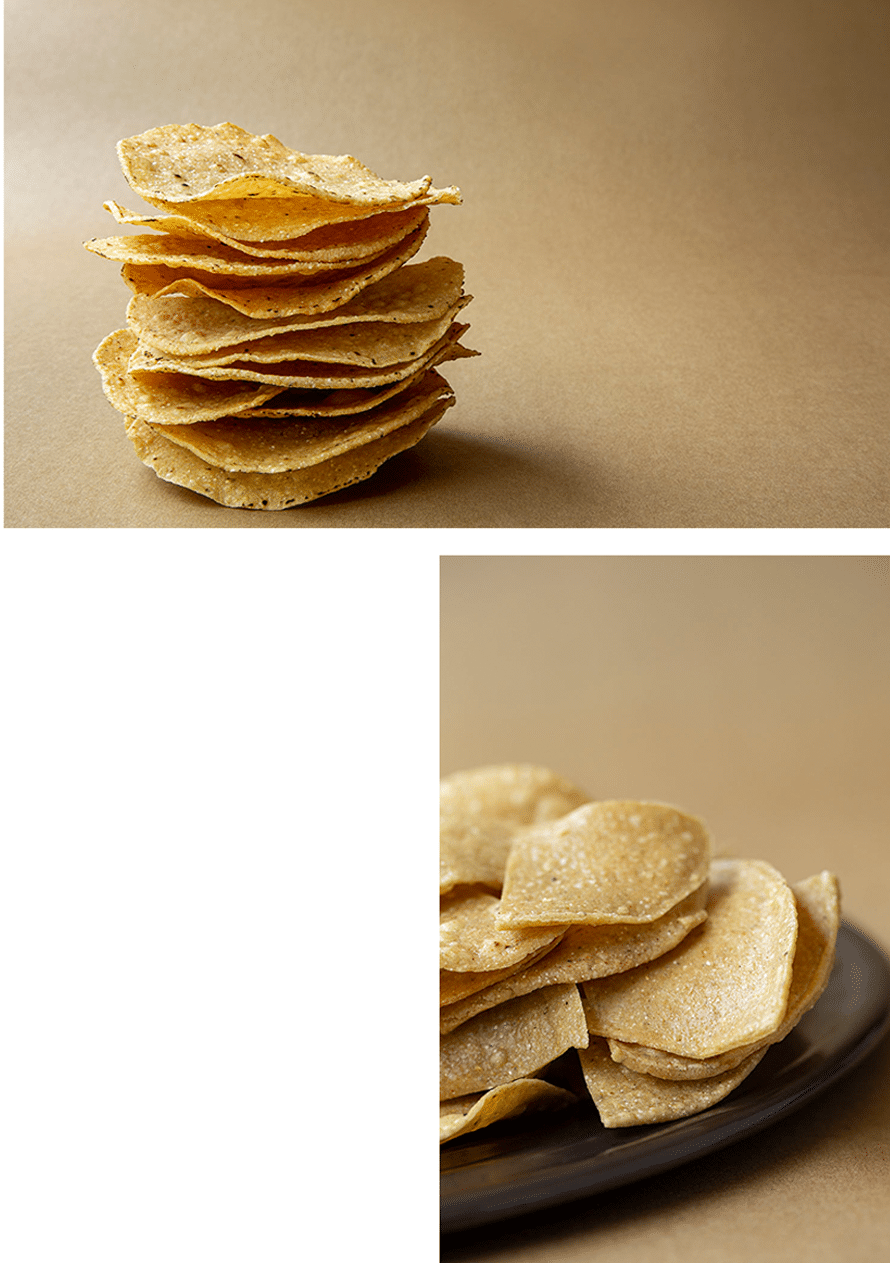

These antojitos made from crunchy maize tortillas can be prepared in the oven, sun-dried, toasted on a hotplate or fried in oil. They are usually eaten with food on top, and their preparation varies from one state to another: in Oaxaca, chileajo tostadas with bean spread are popular; in Mexico City they are topped with cow trotters or shredded chicken; in Hidalgo and Tlaxcala you can try cured tostadas dipped in pulque and dried on a hotplate, although they can also be enjoyed on their own, dipped in sauce or tasty guacamole.

Another use for tortillas are the typical totopos, which are crunchy maize tortilla chips, cut in a triangular shape, used as the base of chilaquiles or as a snack. It is known that from very old times people ate leftover toasted tortillas, known as totopochtli, which in Nahuatl means “toasted”. In Oaxaca there is a very traditional totopo made in special clay pots called “comixcales”.

Tortilla chips are so popular that even today there are commercial snack brands, inspired by their shape and flavor, which are sold all over the world. They are ideal for decorating typical dishes and for eating with guacamole, refried beans, chili sauce or any type of dip.

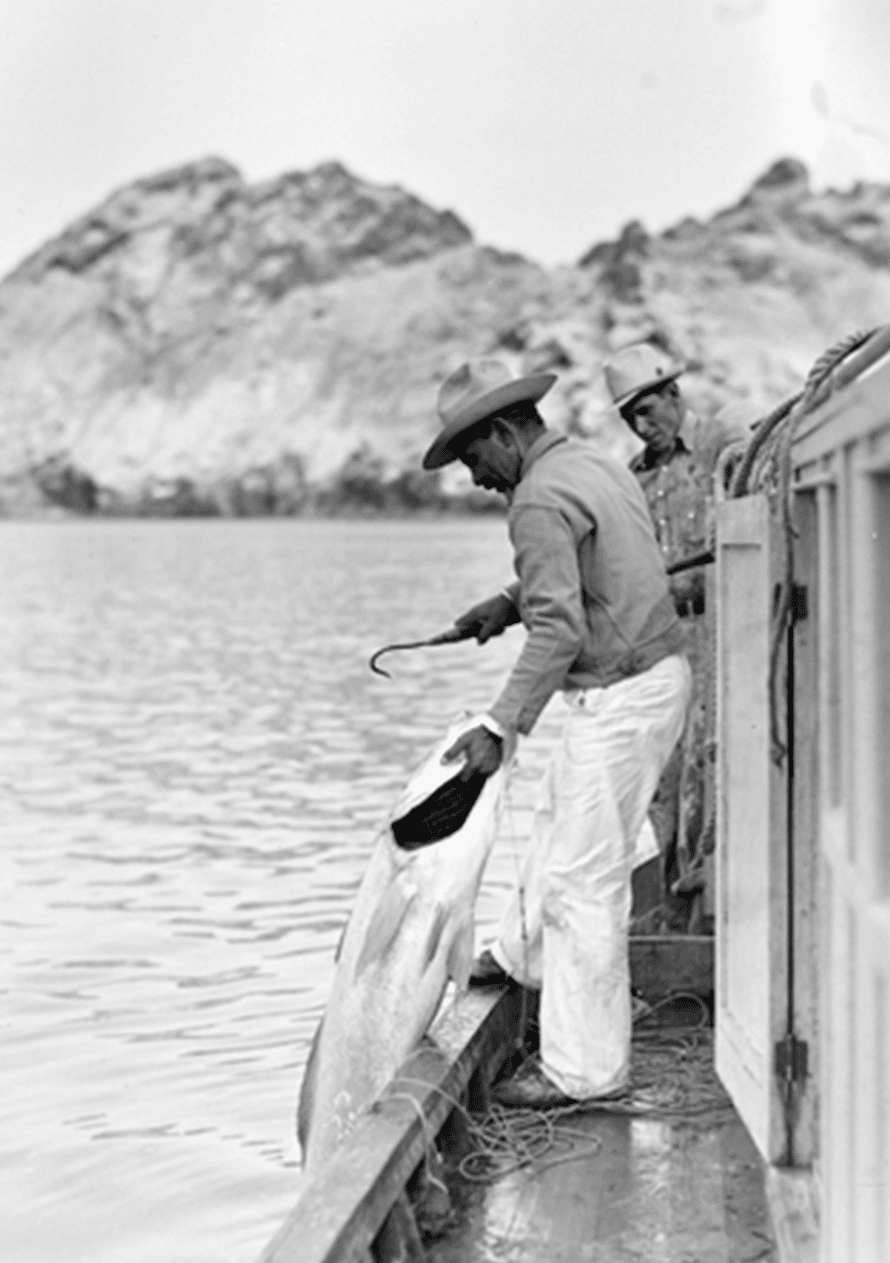

Totoaba macdonaldi is the most famous Mexican fish in the world. This endemic species from the Gulf of California belongs to the drum family; it is a colossal fish that can reach two meters in length and exceed a total weight of over 100 kilograms. This fish is especially coveted in China, where practitioners of traditional medicine say that with its bladder you can make a soup that relieves pregnancy discomfort, enhances sexual appetite and promotes longevity.

Its overexploitation in the eastern market generated severe overfishing, leading totoaba to be officially enlisted as an endangered species in 1975. Unfortunately, this did not stop its consumption, but rather unleashed its clandestine fishing. Illegal trade made it a luxury item that exceeded the price of 8,000 dollars per kilo.

It is currently a protected species and a program for its rescue and conservation has been designed together with the vaquita, a neighboring species and victim of the exploitation of totoaba when caught and drowned in poachers’ nets.

Poet Carlos Pellicer stated that “Mexican people have two obsessions: a liking for death and a love of flowers”. There is a date in the spiritual calendar of Mexicans in which these two elements concur: the Day of the Dead.

It is a celebration without comparison that has its roots in the commemoration of mortuary rituals of pre-Hispanic times in syncretism with the Catholic religious rituals brought by the Spaniards.

In the indigenous worldview it involves a transitory return of souls, who return home to the world of the living to spend time with family members and feed on the essence of food offered to them on altars placed in their honor.

The souls that come back to Earth are guided by mexican marigold petals —especially Mexican marigolds— that families place next to candles and offerings along a path that goes from the cemetery to their house. The deceased’s favorite dishes are carefully prepared and placed around the family altar and grave, amongst flowers, cut tissue paper, sugar skulls and incense smokers burning copal.

In its most authentic expression, it is an intimate act, a rite of domestic simplicity and deep love for those absent, who not in vain are called the faithful departed. Even in the humblest home, the ceremonial act of liberating the family table from its daily use is fulfilled and, for a short time, turned into an altar, decorated with cut tissue paper of the most festive colors. Mole is prepared, as well as pulque, sweets and bread that the dead person being honored enjoyed the most in life, and whose portraits preside over the celebration.

This tradition, passed on from generation to generation, acquires different dimensions according to the community in which it is carried out. In the Maya, Nahua, Zapotec or Mixtec regions this celebration has great relevance. Touching, mysterious, cheerful, ancestral and unique, our Day of the Dead is today a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

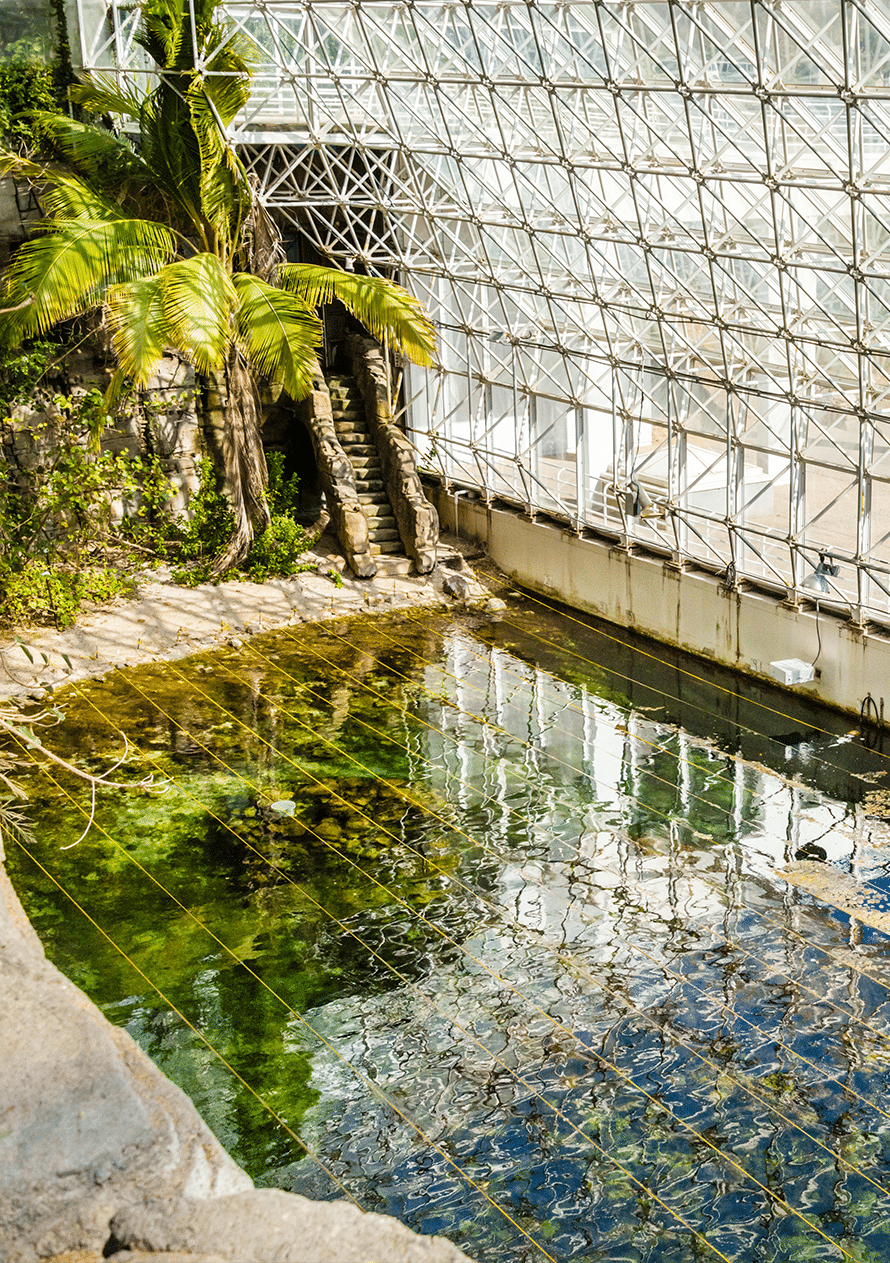

Tridilosa is a construction system based on a mixed three-dimensional structure of concrete and steel, which is composed of tubular elements connected into a pyramidal shape, invented in 1966 by engineer Heberto Castillo Martínez (1928-1997).

Tridilosa replaces girders and reinforced concrete slabs of conventional systems; its essential difference with the latter is that it does not contain filler concrete, resulting in a much lighter, stronger and cheaper structure, since its use represents considerable savings in the use of materials.

Due to its advantages and versatility it has been used to build more than 200 light bridges and floating docks; it can also be found in buildings such as the World Trade Center and the Chapultepec Tower, in Mexico City, as well as several constructions outside the country including the Biosphere 2 facility in Arizona, United States.

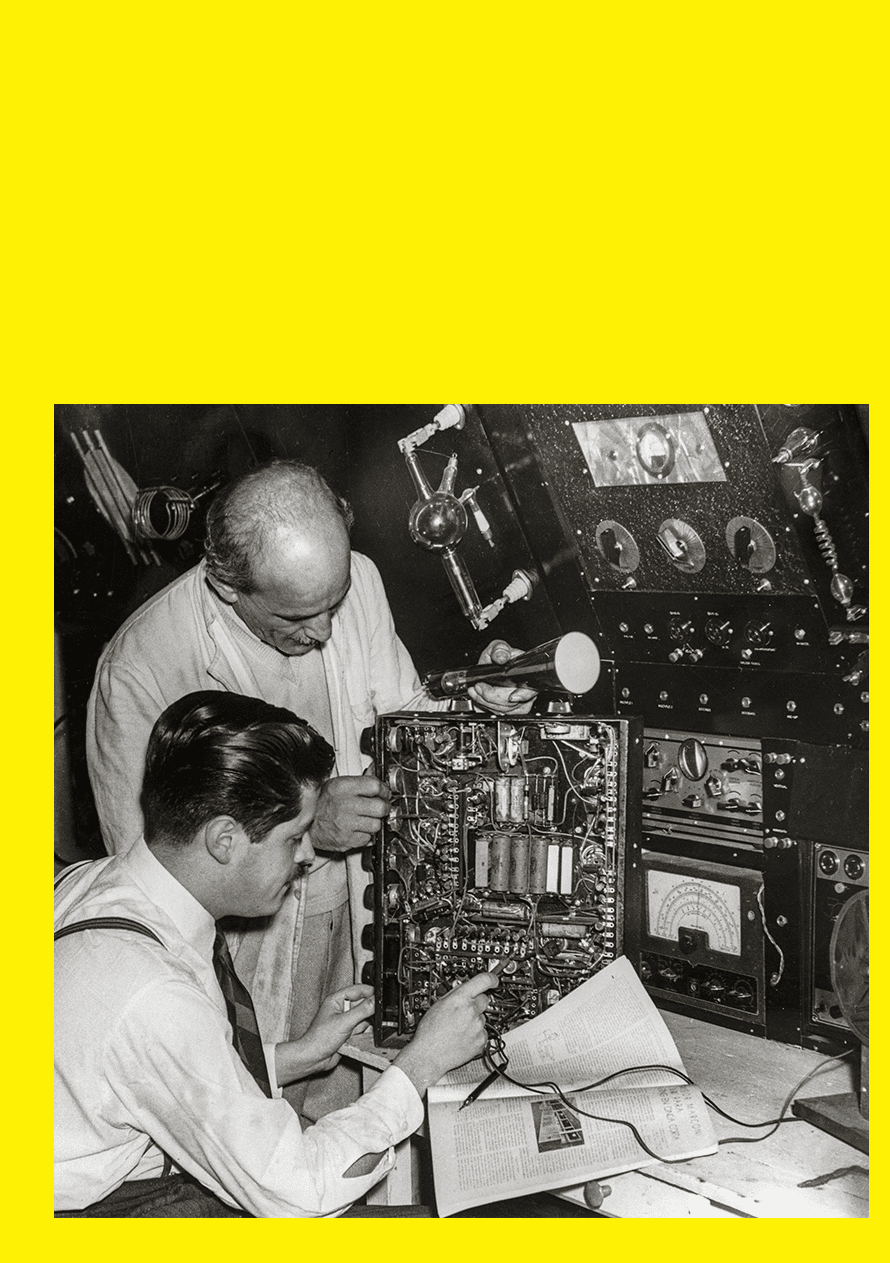

In 1963 the monochromatic screens of Mexican televisions were covered in color thanks to the invention of the versatile Guillermo González Camarena (1917-1965) —inventor, scientist, composer and astronomer— who took several years to perfect the system that revolutionized one of the most important technologies of the past century.

In 1940, when television had been taking over family living rooms for almost two decades, and barely 23 years old, González Camarena obtained the patent in Mexico of the “Trichromatic Sequential Fields System” that used primary colors (red, green and blue) to capture and reproduce images. For twenty years he worked on his invention until, thanks to the concession of Mexican television factory Majestic, he was able to commercially produce color televisions in Mexico.