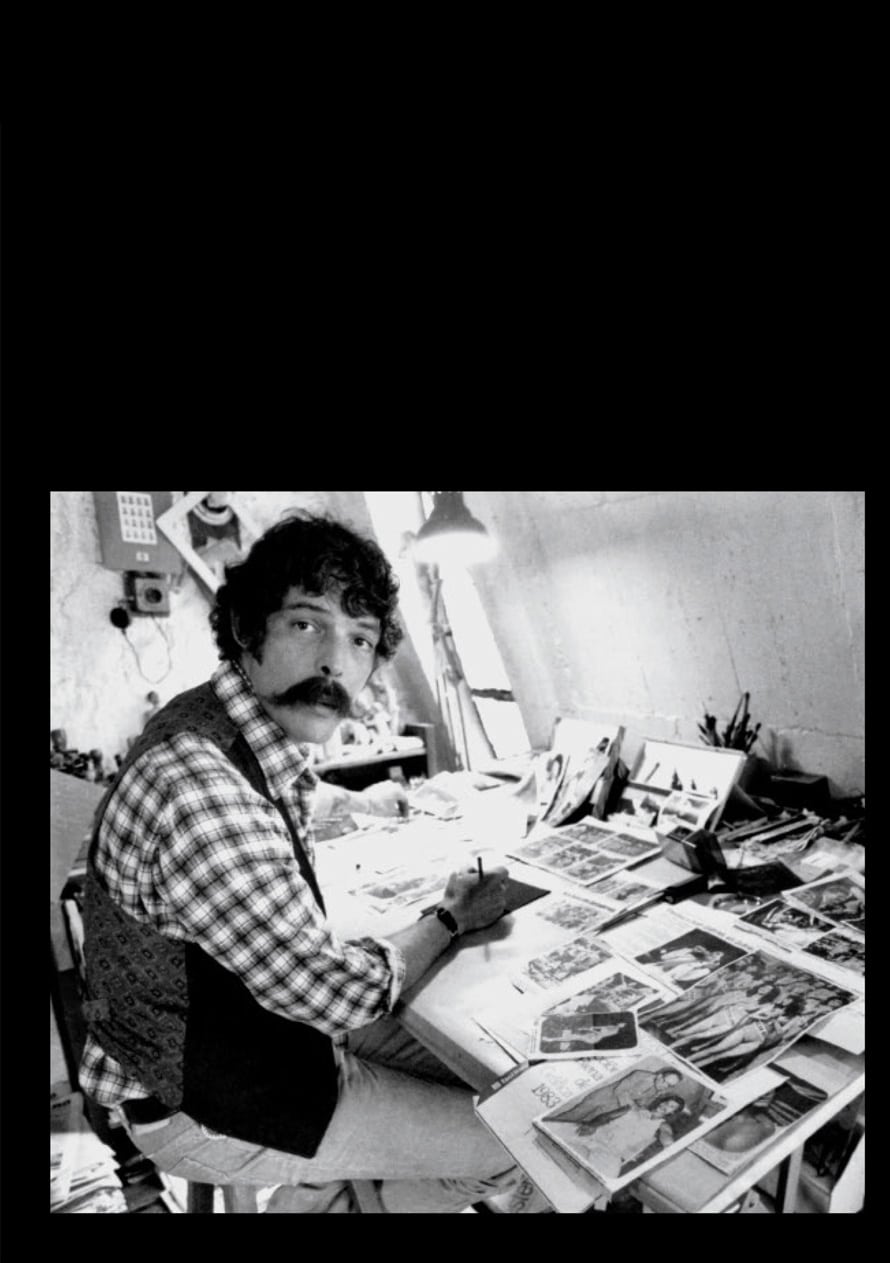

The interests of Felipe Ehrenberg (Mexico City, 1943-Ahuatepec, Morelos, 2017) shifted naturally from graphics to words, from video to performance, and from galleries —or classrooms— to the street. He was a painter, sculptor, engraver, activist, teacher, diplomat, editor, author, and a pioneer of the neographic technique, mimeography and performance.

In England he was founder of the artistic collectives Beau Geste Press and Polygonal Workshop, with which he supported experimental art and neo-Dadaism. In Mexico he helped found the collective Tepito Arte Acá, where not only did he create and teach but, after the 1985 earthquake, he became involved in the coordination of a program to rebuild the neighborhoods of Tepito and San Jacinto, in Mexico City.

He was awarded the Roque Dalton Medal by the Culture and Science Cooperation Council of El Salvador, in 1987. Among other recognitions, he received the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1976 and the Femirama Prize, in Buenos Aires, in 1968. In 1990, he participated as a resident artist in Nexus Press, Atlanta, where he designed and produced his book-object, the Codex Aeroscriptus Ehrenbergensis.

El Chavo del Ocho

“El Chavo del Ocho” is one of the most influential and popular television series in Latin America. Created by actor, writer, producer and musical composer, Roberto Gómez Bolaños, better known as Chespirito, it was broadcasted for the first time on June 20, 1971. They named it after channel 8, the signal where it aired initially, from Televisión Independiente de México, directed at that time by Joaquín Vargas Gómez, before it was incorporated into Televisa.

The program remained on the air for 20 consecutive years, during which its characters El Chavo —Roberto Gómez Bolaños—, La Chilindrina —María Antonieta de las Nieves—, Don Ramón —Ramón Valdés—, Doña Florinda —Florinda Meza—, Professor Jirafales —Rubén Aguirre—, Mr. Barriga —Edgar Vivar—, Quico —Carlos Villagrán—, La Bruja del 71 —Angelines Fernández— and Jaimito, the Postman —Raúl “Chato” Padilla—, lived the gifts and misfortunes within a tenement. Some of its iconic phrases such as “It was accidentally on purpose” and “They have no patience for me”, among many others, were rooted in the Latin American culture.

It is estimated that at its peak an average of 350 million viewers a week watched it. It was dubbed into more than 50 languages and reached countries such as China, Japan, Greece, Morocco and Thailand. The repetitions of its original episodes and the version of “The Animated Chavo” continue to be aired in over 20 countries.

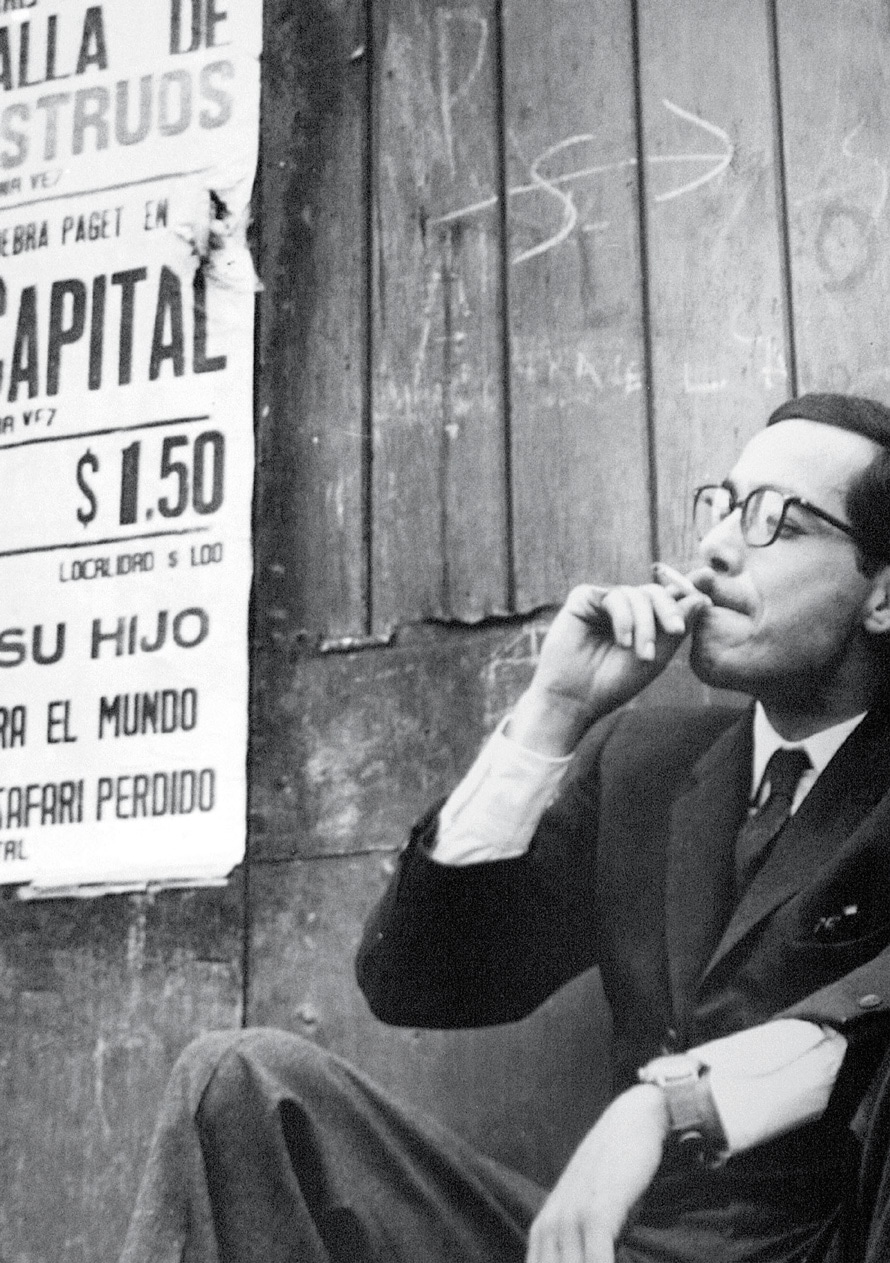

Novelist, poet, essayist, translator and literary critic, Salvador Elizondo (Mexico City, 1932-2006) is one of the most original and innovative writers of his generation. Writer Daniel Sada describes him as “the most unclassifiable author of Mexican narrative”.

In 1965 he received the Xavier Villaurrutia Award for Farabeuf, the foundation stone of one of the most ambitious literary projects of Mexican literature. It revealed a style that took formal experiments to the limit in order to delve into linguistic and philosophical issues, interior life and the construction of reality.

This first novel was followed by The Secret Crypt (1968), El retrato de Zoe y otras mentiras (1969), and El grafógrafo (1972), among others, in addition to Diarios and over one hundred notebooks where he included texts, drawings, photographs, jokes and reflections.

In 1976 he became a member of the Mexican Academy of Language and El Colegio Nacional, where he was a founding member. He also received support from the Ford Foundation to study in New York and San Francisco, as well as the Guggenheim Foundation (1968-1969). In 1990 he received the National Prize for Literature.

Enchiladas are a dish made from soft corn tortillas, lightly fried, rolled or folded in half and covered with sauce; they are usually stuffed with meat, chicken or cheese.

They are one of the most popular specialties of Mexico’s cuisine. There are different versions of enchiladas for each region of the country, which vary depending of the sauce and preparation, although the most popular ones are green, red, and mole enchiladas, garnished with onion rings, cream and grated cheese.

In Mexico City, Swiss enchiladas —green sauce, stuffed with chicken, covered in cheese and baked in the oven— are especially popular. In El Bajío region, the typical enchiladas are the mineras, with guajillo chili and a touch of oregano and cumin; or the ilustradas, the sauce of which is prepared with ancho chili, coriander seeds, cloves and ground cinnamon, among other ingredients.

In Oaxaca enchiladas are prepared either with black mole or Totolapam style, also called enchiladas de coloradito; while in the Huasteca the specialty are the potosinas, where tortilla dough is prepared with chili first. The recipe has so many variations that one could take a gastronomic tour through all the states of the country and find different types of enchiladas in each one.

Caesar salad is a must-have dish in the repertoire of hotel menus and in the most important international cuisine restaurants. It is made with lettuce and crisped bread, seasoned with a mixture of garlic, olive oil, anchovies, hard-boiled egg and Parmesan cheese. Although there are several stories about its origin, it is officially known that it was created in Tijuana, Baja California, in 1924, by brothers César and Álex Cardini.

According to the most widespread version, on July 4, 1924, César Cardini was tending a large number of customers in the Hotel Caesar’s restaurant when the kitchen supplies ran out, forcing him to improvise with what little he found in the pantry. Thus, he created a simple but delicious salad diners fell in love with.

Another story tells that the mother of the Cardini brothers already prepared a similar salad with cheese and bread, known in her hometown in Italy, near Lake Maggiore.

On the other hand, the National Chamber of the Restaurant Industry and Seasoned Foods (Canirac) assures that it derived from an Austrian recipe brought to Mexico by Libio Santini, who was assistant chef at the Caesar’s restaurant.

Beyond the controversy of its origin, Caesar salad traveled from Tijuana to the world and although its recipe has been modified with the passage of time to include chicken slices, bacon or other ingredients, its essence remains intact.

According to Diana Kennedy, who recovered the recipe prepared by Álex Cardini, the dish was originally prepared with slices of bread baked in the oven until crisp and smeared with a mixture of crushed garlic with anchovies and olive oil; the whole romaine lettuce leaves are mixed with egg yolk run under hot water, lime juice, Worcester sauce, grated parmesan cheese, salt and pepper, until well combined.

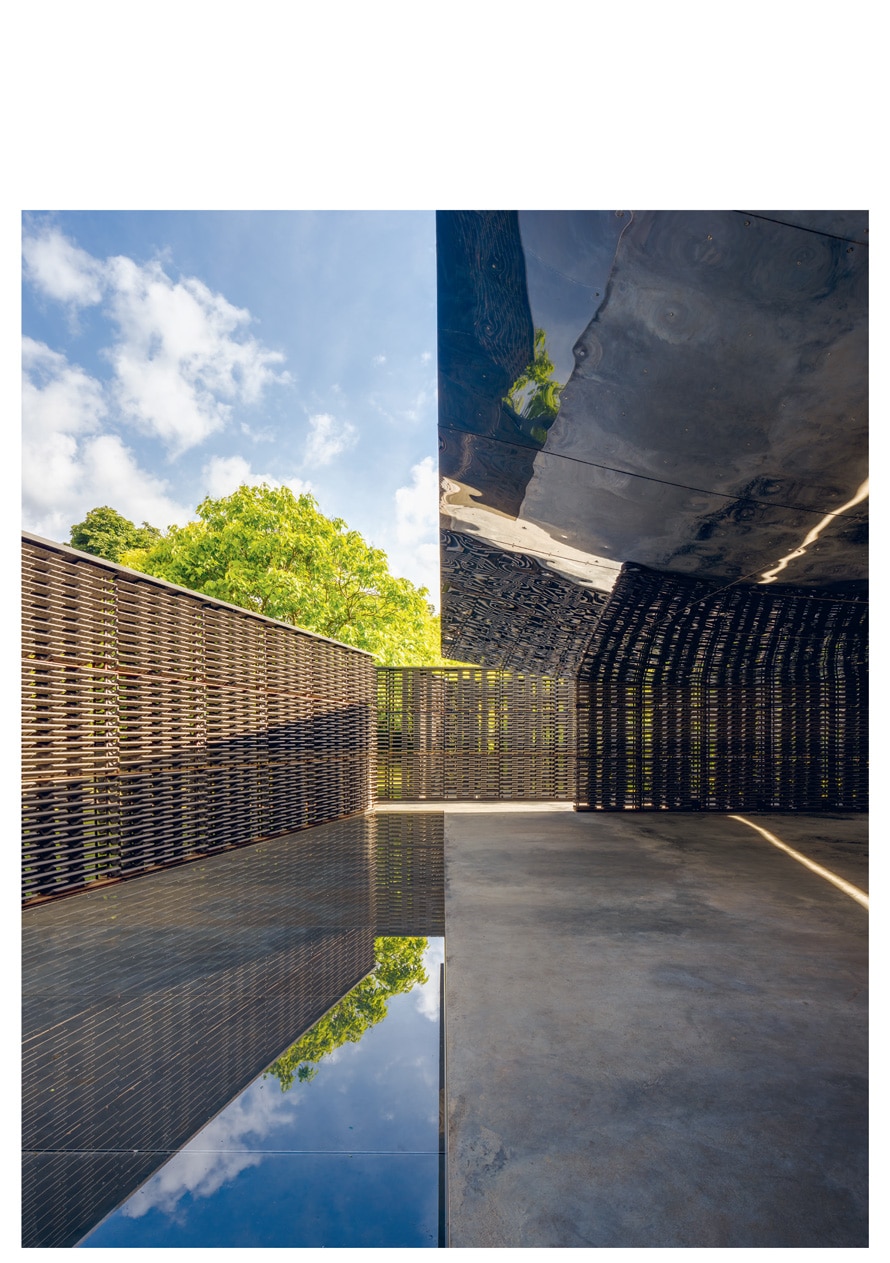

Frida Escobedo (Mexico City, 1979) is one of the most celebrated young promises of Mexican architecture. After studying a postgraduate degree in Art, Design and Public Space at Harvard, she has run her own firm since 2003.

Among other distinctions, she won the Young Architects Forum (2009), awarded by the Architectural Association of New York; she was one of three finalists of the Rolex-Mentor Protégé Award (2013); that same year she was invited to take part in the Lisbon Architecture Triennial and was nominated for the Arc Vision Prize for Women; she participated in the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale in the Swiss Pavilion, and was the winner of the Panorama of Works Award at the 9th Ibero-American Architecture and Urbanism Biennial in Argentina (2014). Her work was exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and at the Chicago Architecture Biennial (2015).

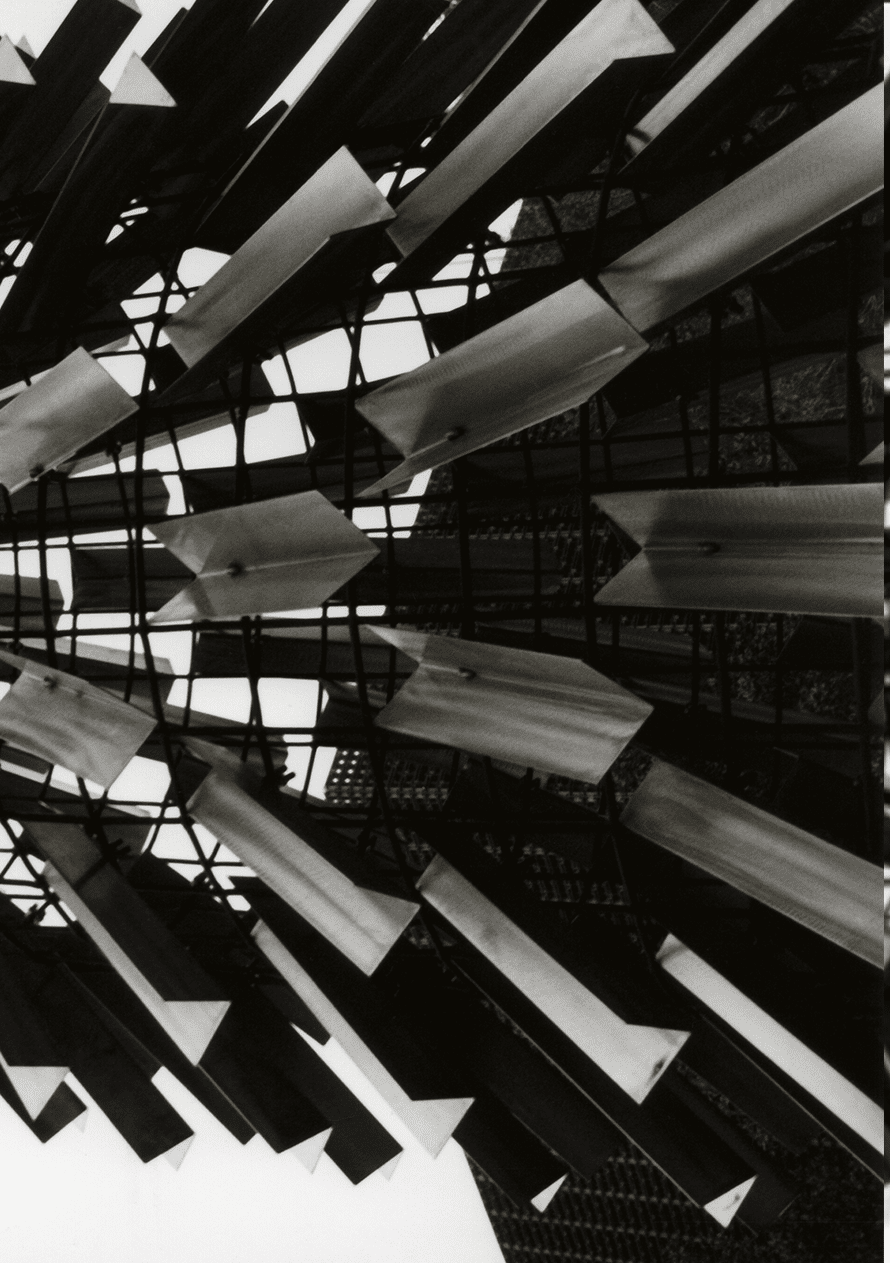

Her most outstanding projects include the restoration of La Tallera, in Cuernavaca, Morelos (2010), a building of invaluable symbolic value, created in the 1960s by David Alfaro Siqueiros; the Civic Stage in Lisbon Architecture Triennial (2013), and her intervention in the Victoria and Albert Museum, in London (2015). She was the first Mexican woman and the second woman in the world chosen to design the Serpentine Pavillion in London (2018).

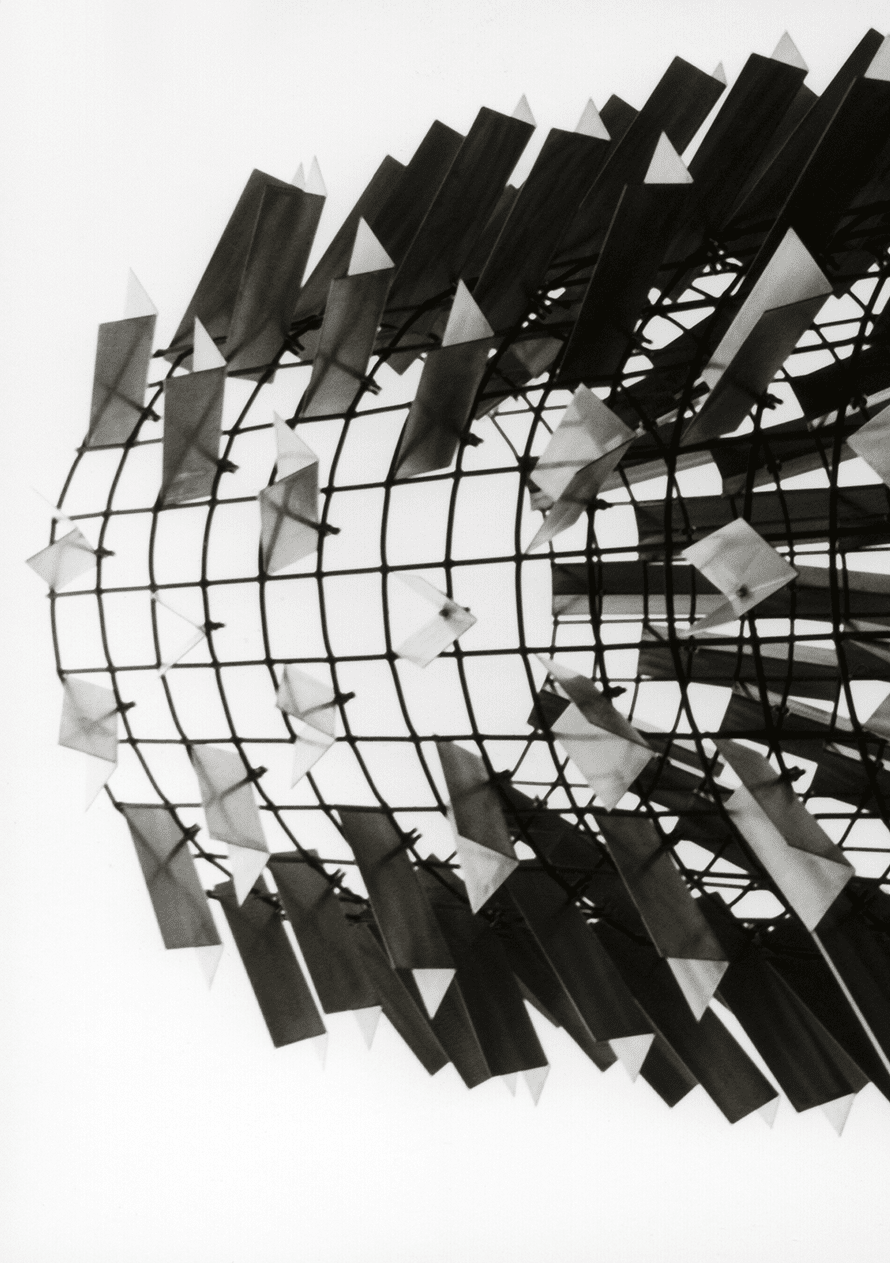

Helen Escobedo (Mexico City, 1934-2010) is remembered as an essential element in the development of the cultural field and museography in our country. With a vision ahead of her time and an authentic passion for artistic work, she pursued the expansion of art spaces from all trenches, as she was a sculptor, designer, museologist, disseminator and museum director.

A precursor of urban art, she traveled through several countries exploring the renewing character of impermanence: social and political nature of art through ephemeral installations, created with a work team and materials found in each place to expose needs, essences and local problems, whether in Tijuana, San Francisco, New Zealand, Cuba, Jerusalem, London or Prague.

In 1997 she completed an art intervention in a park in Hamburg, Germany, with 101 figures made of straw and cloth going towards the train station in the same way as the Jewish community in the Nazi era. This is how Refugees was born, a series that was followed by Exodus and Los Mojados, interventions that evoked the phenomenon of migration in different cultures.

Among her permanent work she participated in the collective creation of the UNAM’s Espacio Escultórico; additionally, her sculpture “Puertas al viento” can be seen along the Route of Friendship, in Mexico City.

Made from maize, esquiate is a multipurpose food: it can be considered a drink or a soup that eases hunger and thirst, while nourishing. The Rarámuris of the Tarahumara mountain range take it daily, since it provides them with enough energy to travel dozens of kilometers without stopping, day and night.

The Tarahumara women thresh the maize —mainly the white crystalline grain, yellow crystalline grain, blue or Chihuahua popping races— and heat it with stream sand in a clay pot called esquitera, until the maize bursts into the shape of popcorn, which they call esquite. From esquite ground on a quern, they extract pinole —roasted ground maize— that they consume dry; when water is added during the grinding they obtain esquiate that can be taken alone, as a drink, or accompanied with flowers or pigweed as a soup.

Thanks to Tarahumara runners’ fame as the best in the world, esquiate has attracted attention, increasing the consumption of pinole as a superfood among the sports community.