Considered the master of Mexican jungles, the jaguar is the largest feline in America and the third on the planet, surpassed only by the tiger and the lion. From the arid Arizona scrublands to the Misiones jungle in Argentina, the power of the jaguar extended through a vast Mesoamerican territory that, with the passage of civilization, became extinct.

In Mexico it is an animal of great symbolic importance, a metaphor of power and strength that embodies beauty, ferocity and the ambivalence of good and evil.

Its presence was constant in the religion and mythology of pre-Columbian cultures such as the Olmec, Zapotec, Toltec, Maya and Aztec. The sovereigns and great warriors incorporated jaguar’s skin, claws and fangs in their attire and weapons to invoke its power.

As a vestige of this tradition —in states such as Oaxaca, Chiapas and Guerrero— rituals, dances, celebrations and the use of the jaguar mask survive: molded in ceramic or carved in wood and polychromed with tooth, skin, bristle or mirror incrustations in Oaxaca; embroidered with beads, created by the Huicholes; the Olinalá lacquered ones in Guerrero, or the masterfully carved helmets in Teloloapan.

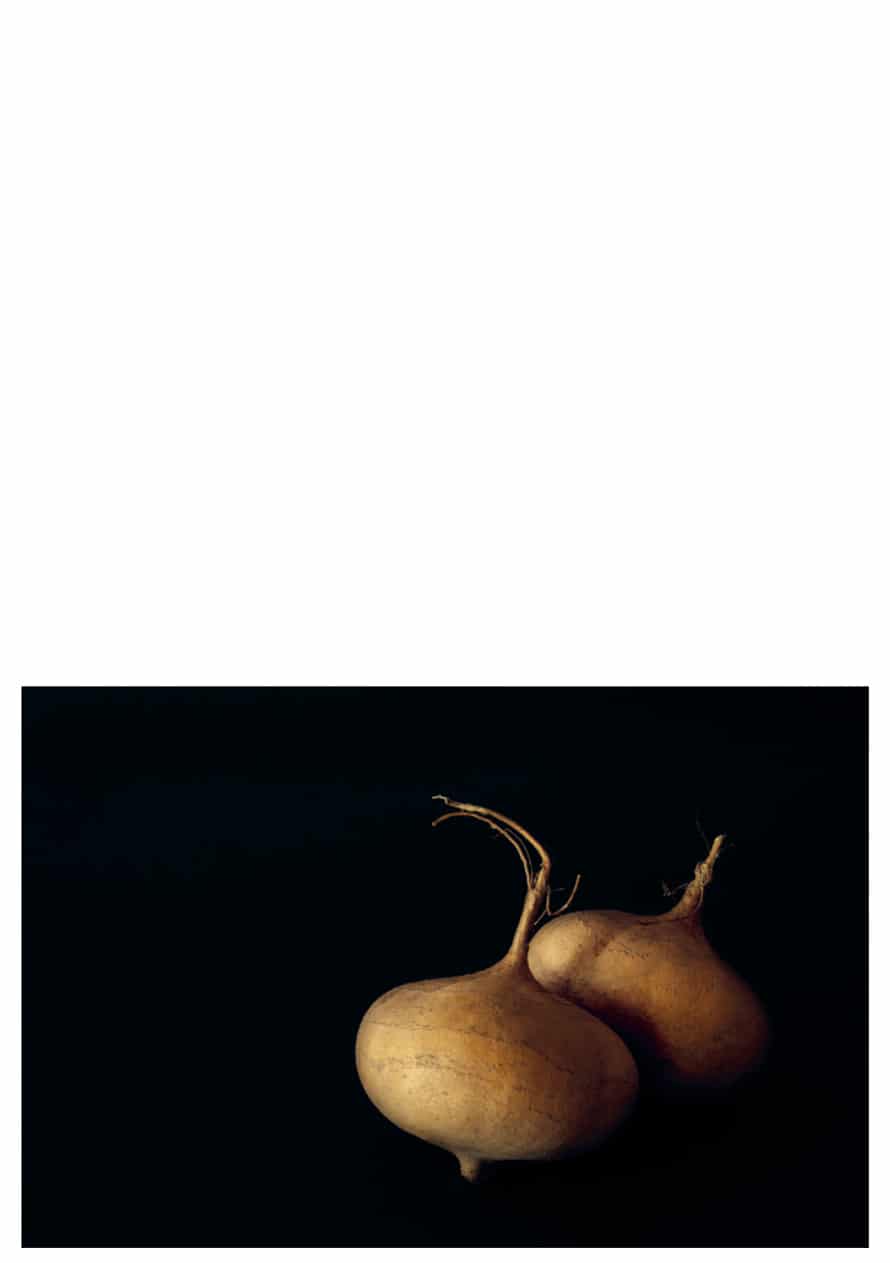

The name of this tuber comes from the Nahuatl word xicamatl, which means “root that gushes juice”. The fleshy and fresh features of its texture made it one of the desserts preferred by the Maya as a means to deal with the heat.

In Natural History of New Spain, Francisco Hernández describes the properties of jícama: “They quench thirst, combat heat and the dryness of the tongue, provide a food very appropriate for those persons who have a fever, and nourish the body [...]. I have heard it is said that these roots have been transported to Spain, preserved with sugar or covered with sand”.26

The Spanish conquerors took this watery root to the Philippine Islands, extending later to many parts of Asia, where it was adopted as an ingredient in several traditional recipes.

Fernando Savater once claimed that José Alfredo Jiménez was “the best poet in Mexico, with the forgiveness of Octavio Paz”,27 and clarified that the phrase was not his but of French writer Jean-Paul Sartre, who once sang Jiménez’s verses “Vámonos, donde nadie nos juzgue...” to Paz, with all the pain in his heart.

José Alfredo Jiménez (Dolores Hidalgo, Guanajuato, 1926-Mexico City, 1973) has gone down in history as “the poet of desolation”. For decades, his lyrics have accompanied broken hearts, those who suffer, those in love and those who, despite marginalization, continue to sing, still convinced that “life is worth nothing”.

The lyrics of “Hijo del pueblo” renewed the ranchera genre and his 280 songs make up a living and eternal heritage that spreads in the echoes of mariachis, whether in Garibaldi or in any corner of the world where the chords of “El rey”, “En el último trago”, “Si nos dejan”, “Que te vaya bonito” or “Un mundo raro” are heard.

September 18 has been recorded in the history of Mexican sports as the day Soraya Jiménez Mendivil (1977-2013) became a legend when she crowned herself as the first Mexican woman to win a gold medal in the Olympic Games and —to date— the only Mexican Olympic champion in weightlifting.

It was the year 2000, despite being only 23 years old and facing many difficulties, Soraya managed to go to Sydney, Australia, being practically invisible: registered in a competition “for men”, and away from the spotlight that focused on the Olympic hope placed on others athletes.

Something unusual happened during the course of the weightlifting runs that began to attract the attention of international media. A Mexican woman gradually added weight to the bar and left her opponents behind in the 58-kilogram category. In the last run, with a single movement, Soraya left millions of spectators breathless as she lifted 222.5 kilograms, which she held in the air for more than the ten mandatory seconds.

Unfortunately, the gold medal was not enough to brush away the difficulties faced by the strongest woman in the world; she died at age 35, after constant health complications.

Shortly after her death, the Senate of the Republic paid her a tribute and recognized her career and contributions to Mexican sport, which was received by her parents.

Xiltómatl, a Mesoamerican ingredient, of which the Nahuatl root means “navel”, was domesticated by the Aztecs, who offered the best examples of this fruit, accompanied by flowers and copalli, to Tlazotéotl, goddess of passion and lust.

From Mexico it traveled to the Old World in the hands of Hernán Cortés. In Spain, for a long time its use was reduced to an ornamental plant, because they believed it was poisonous.

It was in Italy where they discovered its quality to adapt and mix with other ingredients, so they named it pomodoro, that is “golden apple”, and perfected its cultivation until it became an increasingly large, juicy, strong fruit of multiple and voluptuous shapes. Presently, over two thousand tomato varieties are known and it is considered one of the most important ingredients on the planet. The current Mediterranean diet and innumerable Mexican dishes would be inconceivable without it.

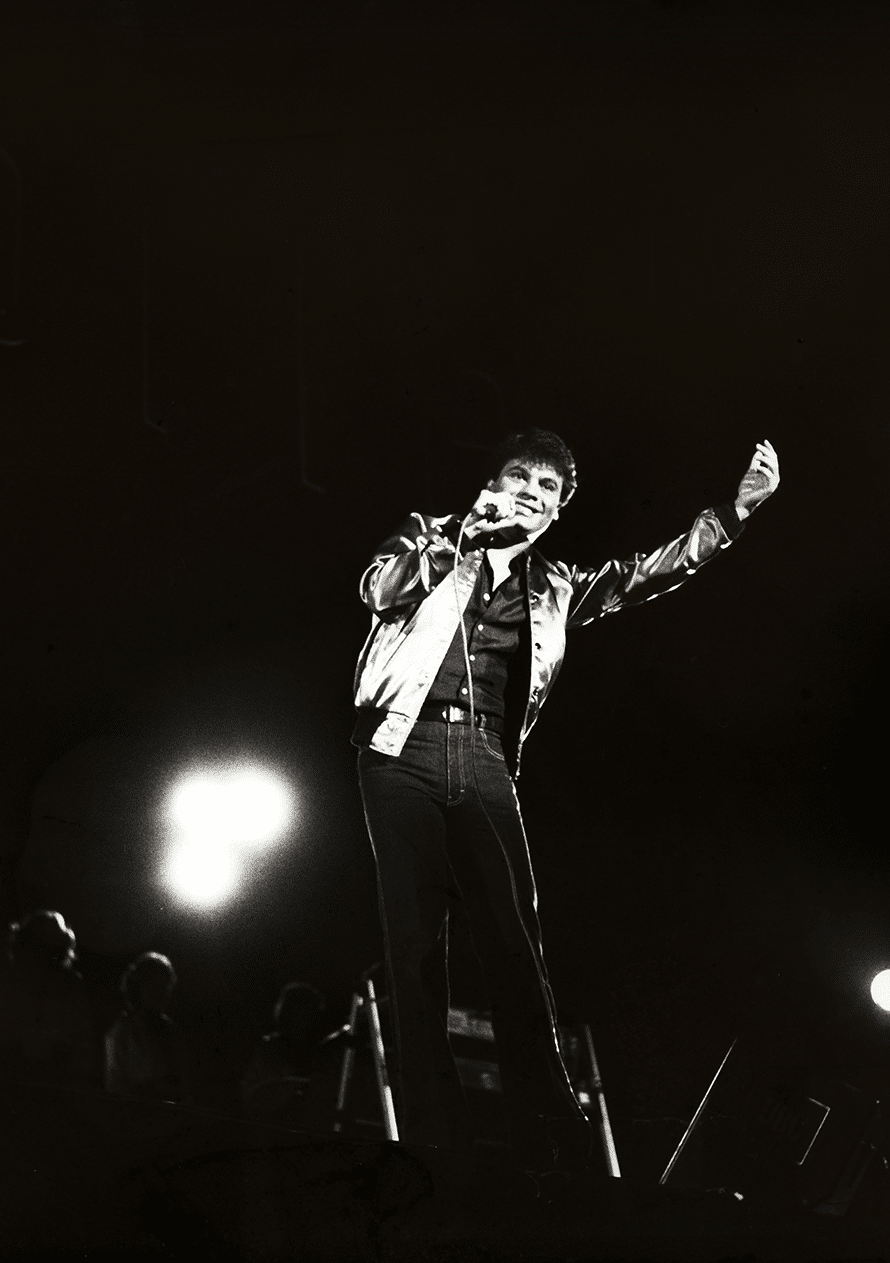

For over 40 years, Juan Gabriel brought his beloved Mexican music to millions, transcending borders and generations. To many Mexicans and people all over the world, his music sounds like home.28

Barack Obama

According to the records of the Mexican Society of Authors and Composers (SACM) every 40 seconds, one of Juan Gabriel’s (1950-2016) songs of is heard in some corner of the world.

“The Diva of Mexico” made his life an ode to resistance. As Alberto Aguilera Valadez he overcame family abandonment, misfortune and iniquity. Parácuaro, Michoacán, was his birthplace, but the streets of Ciudad Juárez were his up-bringing and school.

In jail he acknowledged the freedom of music and became Juan Gabriel, the phenomenon that passed over all taboos to rise as a standard of dissidence: while his passionate style captivated millions, his mere presence challenged stereotypes from machismo to classism ideas.

Under his authorship there are 1,800 registered songs —sometimes corny, sometimes melodramatic, always endearing— that evoke love, heartbreak, the homeland and the joy of living. The rights to those songs were waived over 1,500 times to be interpreted by singers who recorded them even in English, Turkish, Japanese, German, French, Italian, Tagalog (language of the Philippines), Greek, Papiamentu (from Curaçao) and Portuguese.29

His death represented an international mourning.

The writ of amparo is a contribution of Mariano Otero Mestas (Guadalajara, Jalisco, 1817-1850) to Mexican and international law. This legal tool was developed in the 19th century and guarantees the protection of citizens against possible abuses or arbitrary acts of authority.

In 1842, the jurist was elected as representative in the Constituent Congress, convened to amend the Seven Constitutional Laws of the Centralist Regime of 1836. Otero belonged to the drafting commission and pronounced himself for the establishment of a federal and democratic Republic. His ideas were not well seen by Antonio López de Santa Anna, who closed down Congress and ordered Otero to be detained, along with others involved, who were held incommunicado for 44 days, accused of violating the peace of the Republic.

After his release and having been arrested without a clear crime to condemn him, Mariano Otero considered that a legal instrument should be formulated to protect the rights and guarantees of the people before the authority. With the support of Manuel Crescencio Rejón, he was able to incorporate the writ of amparo into the Constitutive and Reform Act of 1847, establishing it at the federal level. Later it was incorporated into the Constitutions of 1857 and 1917.

With a legal vision ahead of his time, Mariano Otero is appreciated as one of the forefathers of the Mexican State. The writ of amparo opened the possibility for the constitutional protection of human rights that has inspired similar figures in other countries.

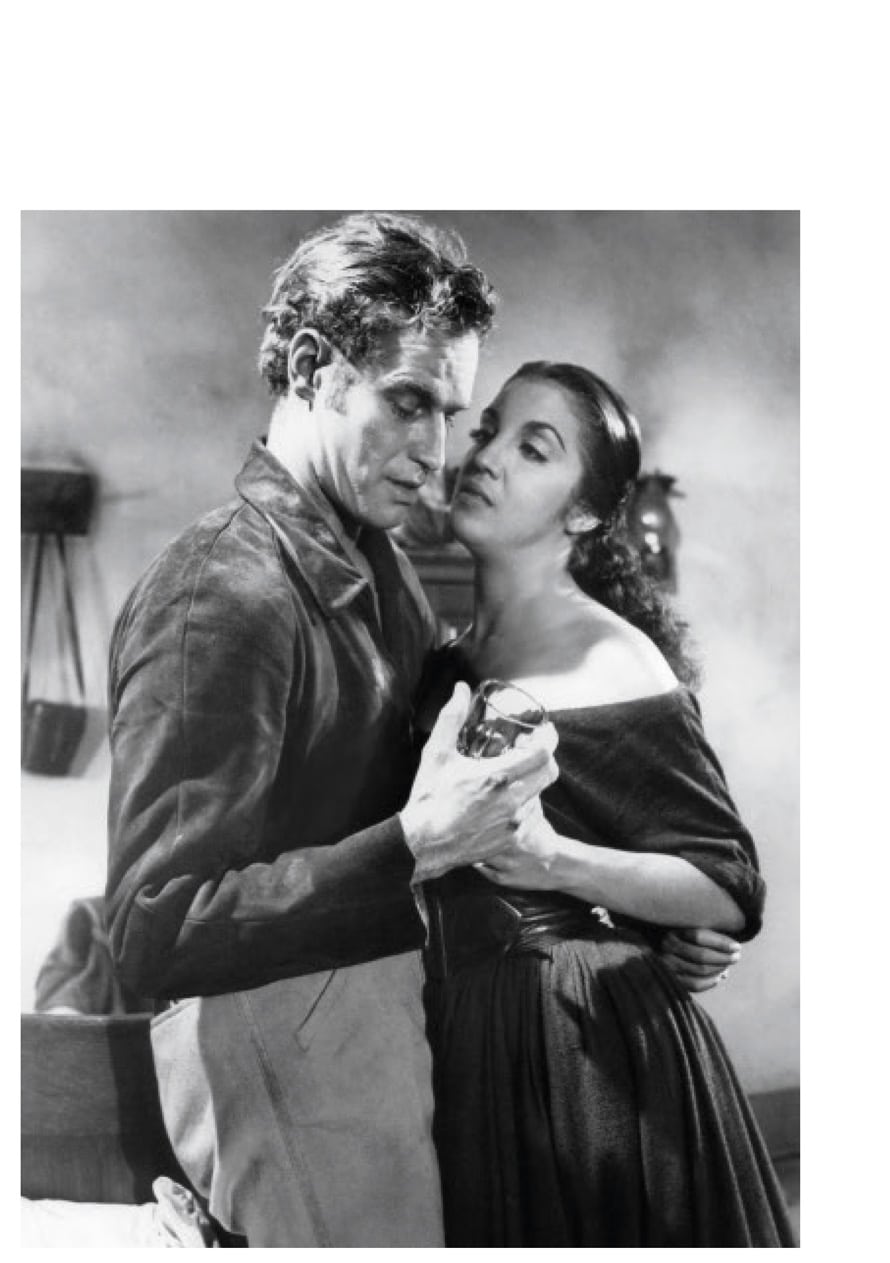

When she was just 15 years old, the talent of María Cristina Jurado García (Guadalajara, Jalisco, 1924- Cuernavaca, Morelos, 2002) caught the attention of director Emilio “El Indio” Fernández, who offered her a role in his debut feature film La isla de la pasión, but the teenager did not have her parents’ permission to act, so she had to reject the part.

Later, in 1943, still without permission, she debuted in the film No matarás, directed by Chano Urueta, and became known as Katy Jurado. By 1951 she had already moved to Hollywood, where she worked as a film columnist, radio journalist and bullfighting critic.

It was actually in a bullfight where she met actor John Wayne and filmmaker Budd Boetticher, who invited her to join the cast of film The Bullfighter and the Lady (1951). Thus began her successful career, becoming a regular character in Western films of the time. Overtime, she was offered more complex roles, and she specialized in playing perverse and seductive women. She worked in over 60 films in which she shared credits with figures such as Charlton Heston, Marlon Brando, Grace Kelly and Elvis Presley.

She was the first Latin American actress to win a Golden Globe, for her performance in the film High Noon (1952), and the first to be nominated for an Academy Award in the category of Best Supporting Actress for her performance in Broken Lance (1954), opening the doors of the movie mecca to her successors.