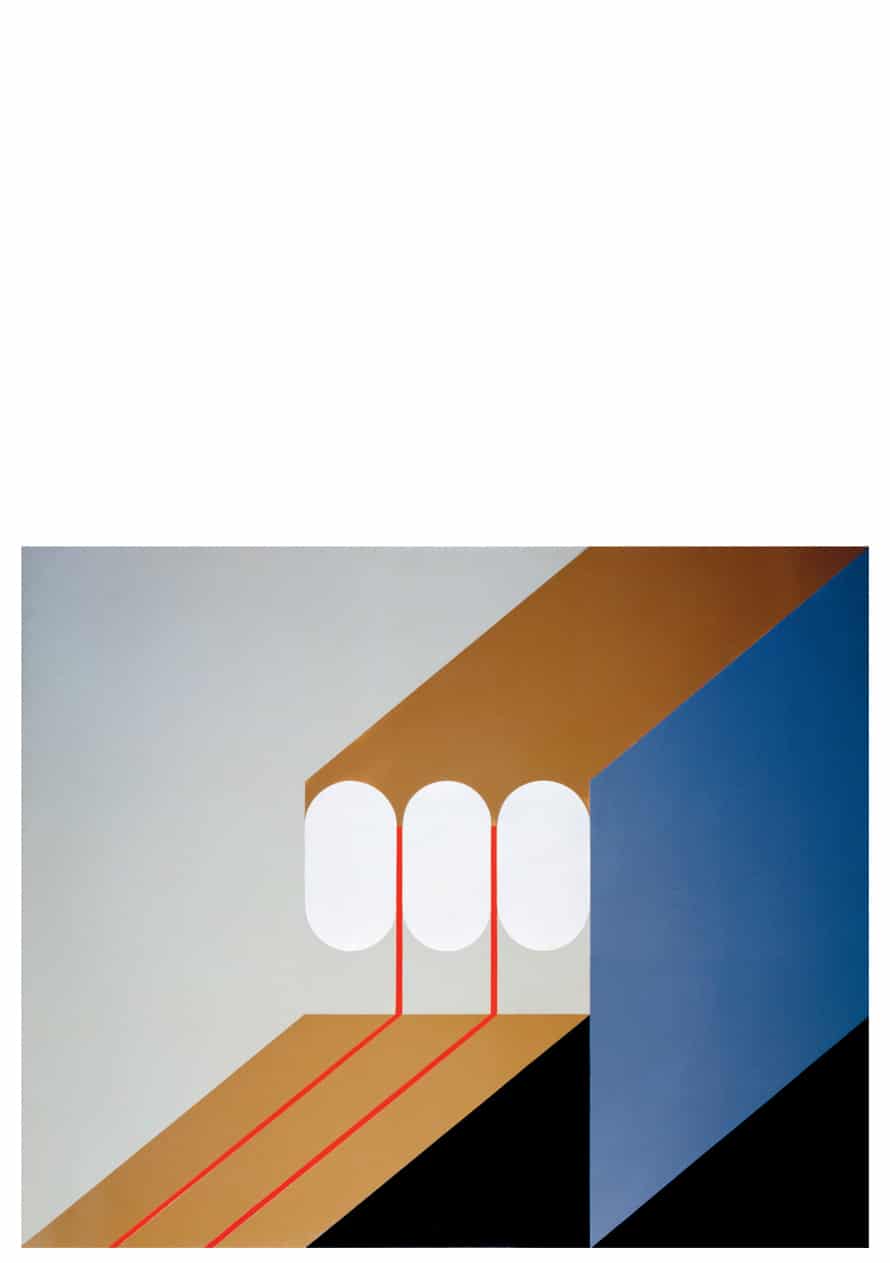

Artist born in Valparaíso, Zacatecas, in 1928; pioneer of abstract art in our country and an essential member of the Rupture Generation, a movement of abstract artists openly confronted with the nationalist tradition of the Mexican School of Painting.

He studied at the National School of Painting, Sculpture and Engraving “La Esmeralda”; at the UNAM’s National School of Plastic Arts; at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and the Académie Colarossi, both in Paris.

Felguérez started out in artistic life as a sculptor in Paris, being a pupil of cubist artist Ossip Zadkine. He made his first solo exhibition at the French Institute for Latin America in Mexico City in 1954, and in 1955 he won his first sculpture prize at the Casa de México in Paris.

His pictorial and sculptural production is vast and is distributed inmuseums and private collections in Mexico and abroad; he also has more than 50 murals and sculptures in public spaces. In recognition of his career and artistic contribution, in 1998 the Manuel Felguérez Museum of Abstract Art was founded in Zacatecas, whose collection was largely donated by the artist himself.

Throughout his career he has received the French Government Scholarship (1954); the Second Painting Prize in the First Triennial of New Delhi, India (1968); the Grand Prize of Honor at the 13th São Paulo Biennial in Brazil (1975); the Guggenheim Fellowship (1975); and the National Arts Award in Mexico (1988).

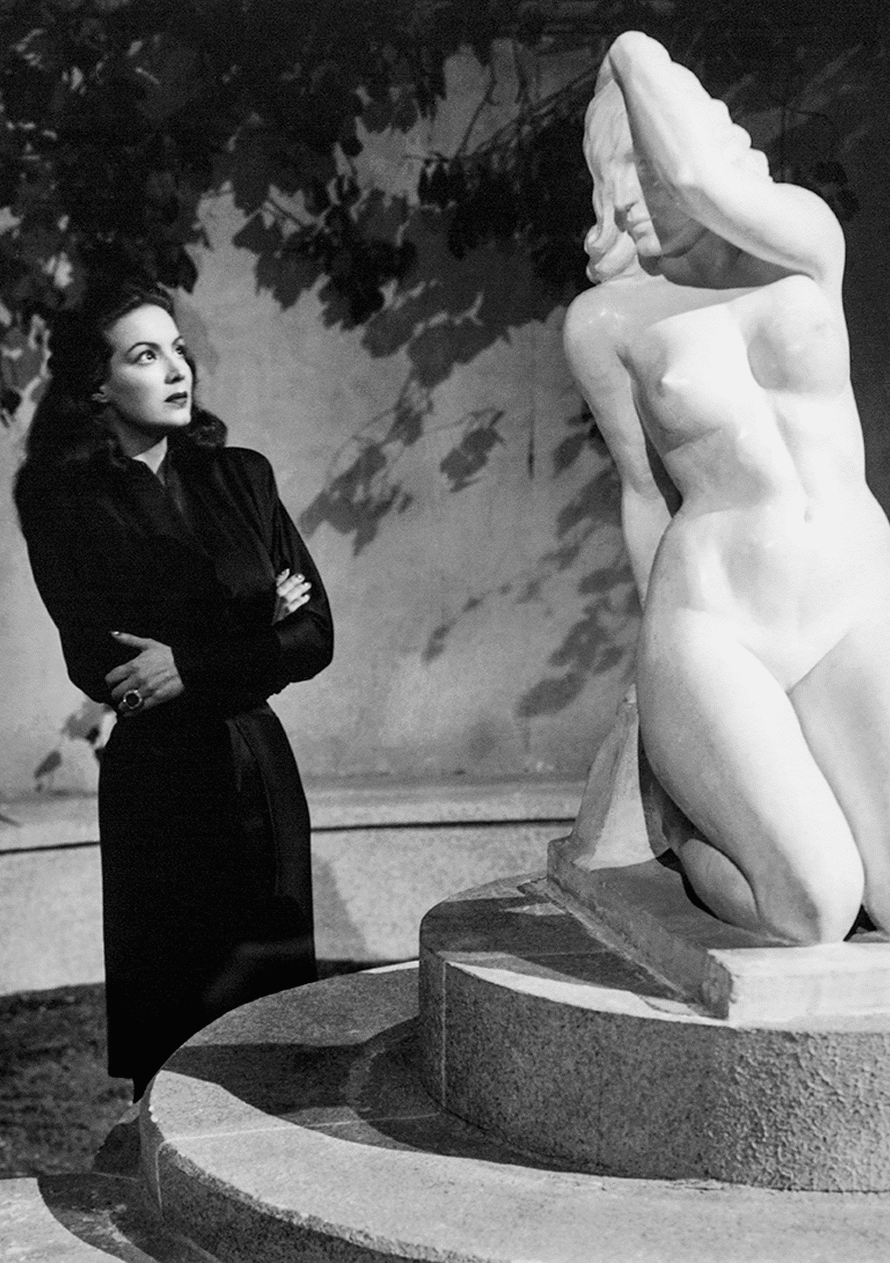

Considered one of the most beautiful women in the world, actress María Félix (Álamos, Sonora, 1914- Mexico City, 2002) always stood out for her impressive personality on and off the big screen.

She debuted in the film The Rock of Souls (1942), which marked the beginning of a successful film career that included 47 films shot in Mexico, Spain, Italy, France and Argentina, among which Tizoc (1957), La bandida (1963) and Doña Bárbara (1943) —for which she would always be remembered as La Doña— are some of the most remarkable.

Some people claim that the close up shot was invented with cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa’s famous approach into her eyes in the film Enamorada (1946).

The memory of the great Mexican film diva is still alive, immortalized in the seventh art, in her controversial interviews and in music, through song “María Bonita”, composed by Agustín Lara.

Rooted in the post-revolutionary nationalist culture, Emilio Fernández Romo (Mineral del Hondo, Coahuila, 1904-Mexico City, 1986), better known as “El Indio”, established himself as one of the most significant filmmakers of the Golden Age of Mexican cinema. He used to state without hesitation: “There is only one Mexico, the one that I invented”.

From a very young age he enrolled in the troops of the delahuertista rebellion that fought against the government of Álvaro Obregón. He was imprisoned, but not for long, because he managed to flee and reach the United States.

During his exile he lived in Los Angeles, where he worked as an extra and stand-in for stars in Hollywood. It is said that during this time he posed as a model for the Oscar statuette at the invitation of his friend Dolores del Río, who considered that his physique was ideal for the sculpture that her husband, art director Cedric Gibbons, had been commissioned to work on.

Upon his return to Mexico and influenced by Sergei Eisenstein, he began a film career that included more than 120 films in which he performed as an actor, director and screenwriter, including: María Candelaria and Flor Silvestre, starring Dolores de Río (1943); The Pearl, the first film in Spanish to win a Golden Globe (1945); and Enamorada (1946), one of the best-known films from our national cinema. It was recently presented at the Cannes Film Festival by director Martin Scorsese in a special screening.

Cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa (Mexico City, 1907-1997) has been granted a glorified status in the Mexican film industry, since his lens composed a chiaroscuro language that defined the idealized image of Mexico providing substance to our memory and identity.

It is said that Diego Rivera named him “the fourth muralist”, because he managed to find on the screen a new media from which “traveling murals” merged their perspective with inspirations taken from the work of José Guadalupe Posada, Leopoldo Méndez, José Clemente Orozco, Tina Modotti, Manuel Álvarez Bravo and other great painters and photographers of the time, representatives of the Taller de Gráfica Popular and of the movement concerned with constructing a nationalistic view through artistic activity.

The first film that credited Figueroa as a co-cinematographer was ¡Que Viva México! (1932), by Sergei Eisenstein, in which he worked with Eduard Tisse, one of his greatest influences.

His filmography includes 210 titles in a career of just over fifty years, during which he collaborated with directors such as “El Indio” Fernández, Luis Buñuel and Roberto Gavaldón, in films that continue to be a reference like María Candelaria (1943), Enamorada (1946), The Young and the Damned (1950), Soledad’s Shawl (1952) and Macario (1960).

José Antonio Alzate y Ramírez (Ozumba, State of Mexico, 1737-1799) was one of the most distinguished polymaths of his time who invented, in 1790, the “floating automatic shutter”, better known as ballcock.

At the end of the 17th century water waste represented a serious problem for Mexico City, due to the large quantities that spilled out from fountains because they did not have a system that would close them when full. The solution was this simple device that controls the exit of liquid from a container to avoid its waste. Its most common use is in toilet systems and water tanks. It has saved millions of liters of water.

To pay homage to its inventor, for this and many other contributions in various fields, the Antonio Alzate Scientific Society was founded in 1884, which later became the National Academy of Sciences.

Sculptor, designer, illustrator and surrealist painter Pedro Friedeberg was born in Florence, Italy, in 1936, but he claims to have known no other country than Mexico. He disembarked in this country when he was barely three years old and grew up in a rickety house in the San Rafael neighborhood of Mexico City. Later he studied architecture, but while he was being taught angles and functional theories, he dreamed of Gaudí’s sacred geometry and fantastic organic architecture.

He worked for a while with Mathias Goeritz; however, he left the modern movement to join the rebellion of surrealism along with Remedios Varo, Edward James, Wolfgang Paalen and other artists; although only he and Frida Kahlo were acknowledged by André Bretón as part of the surrealist movement.19

In 1962 he created the hand chair, which is both a sculpture and a curious piece of design, originally made of wood finished in gold leaf, recognized and admired worldwide.

He does not remember for sure if the inspiration for this piece came to him through the fragments of a dream or from a Roman statue he saw on the Capitoline Hill, but from that same place other objects arose including tables, lamps, armchairs and countless paintings and artistic pieces in which eyes, hands, feet and psychedelic visions of his creative universe are mixed, full of humor and symbolism.

His exhibitions are innumerable and his “unauthorized” memoirs have been immortalized in the book that he dictated to poet José Miguel Cervantes, titled De vacaciones por la vida.

“Yellow beans, red, white and the smaller ones, those that are marbled, others of very diverse colors, and those that are very big like broad beans, which are referred to in their language as ayecotli”,20 is how Bernardino de Sahagún describes the great variety of beans found in the New Spain.

Beans are a symbol of our national identity and a pillar for the country’s economy; together with chili and maize, they constitute the great Mexican gastronomic triad.

Currently over 150 varieties of beans are known in the world. In France, all types of beans are called haricot, referring to ayecotli.

Beans have been consumed since pre-Hispanic times, taking advantage of all the life cycles of the plant: seedlings eaten as pigweed, green beans —immature pods— and the cooked mature grain.

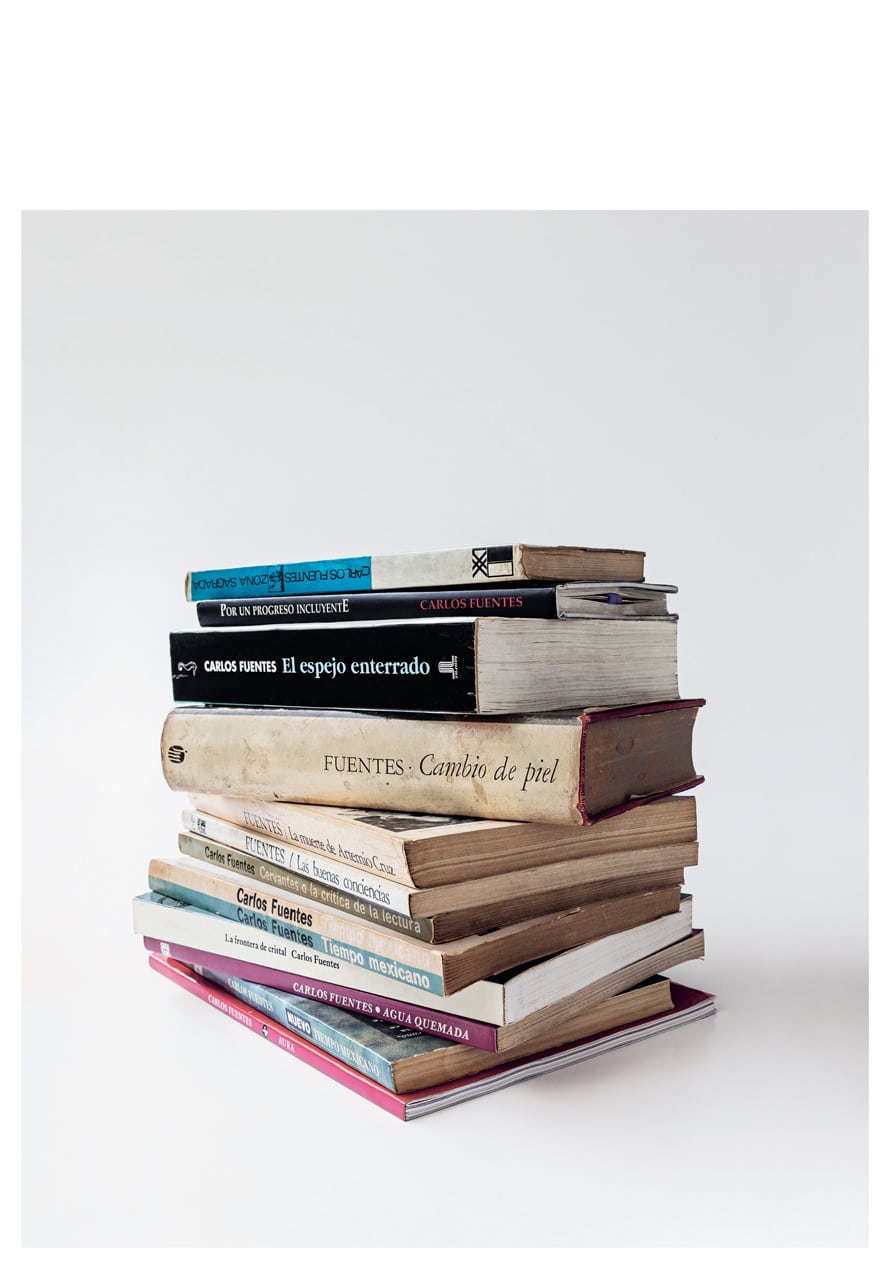

Carlos Fuentes (1928-2012) was a writer and diplomat. He is one of the main representatives of the Latin American Boom, a literary movement that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, and included among its ranks writers such as Julio Cortázar, Mario Vargas Llosa and Gabriel García Márquez.

This explosion of young narrative challenged the established conventions of the Latin American literature of the time and caused the flowering of an aesthetic sense of its own, with a free use of language and subject, which responded to the political and social influence of current affairs in the country of each of its representatives.

In this context, Fuentes was well received since the publication of his first novel, Where the Air is Clear (1958); later, Aura and The Death of Artemio Cruz (1962) consolidated as two of the most important novels in Mexican literature. He is the author of twenty novels and an important number of essays, short stories, plays and screenplays.

Awards were a constant in his life, due to the brilliant development of his career. In addition to several medals and decorations, he obtained over twenty honorary doctoral degrees granted by several universities —among them Harvard and the National Autonomous University of Mexico—, in addition to receiving the National Prize for Science and Arts in Linguistics and Literature (Mexico, 1984), the Miguel de Cervantes Prize (Spain, 1987), the Prince of Asturias Literature Prize (Spain, 1994), and the Grizane Cavour International Prize (1994), among many others.