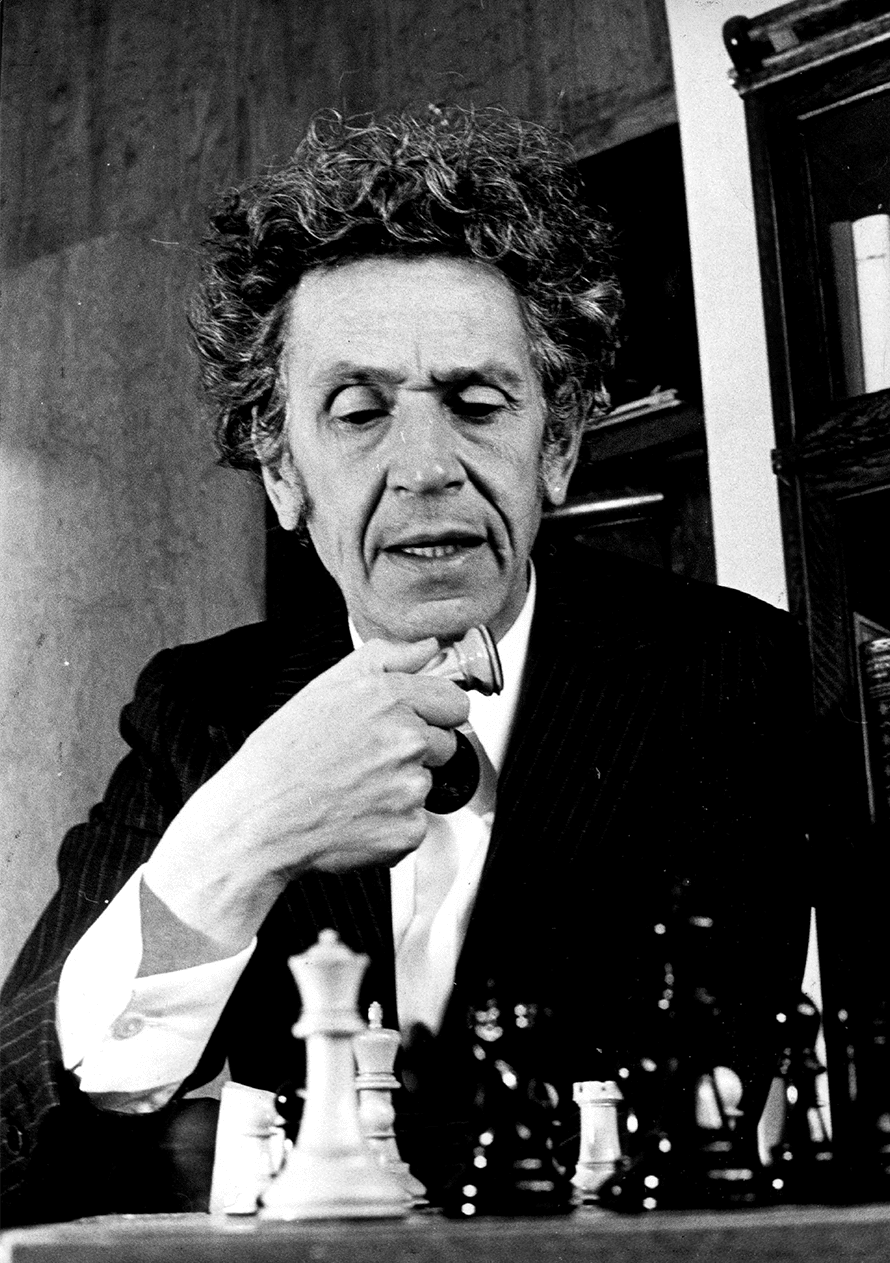

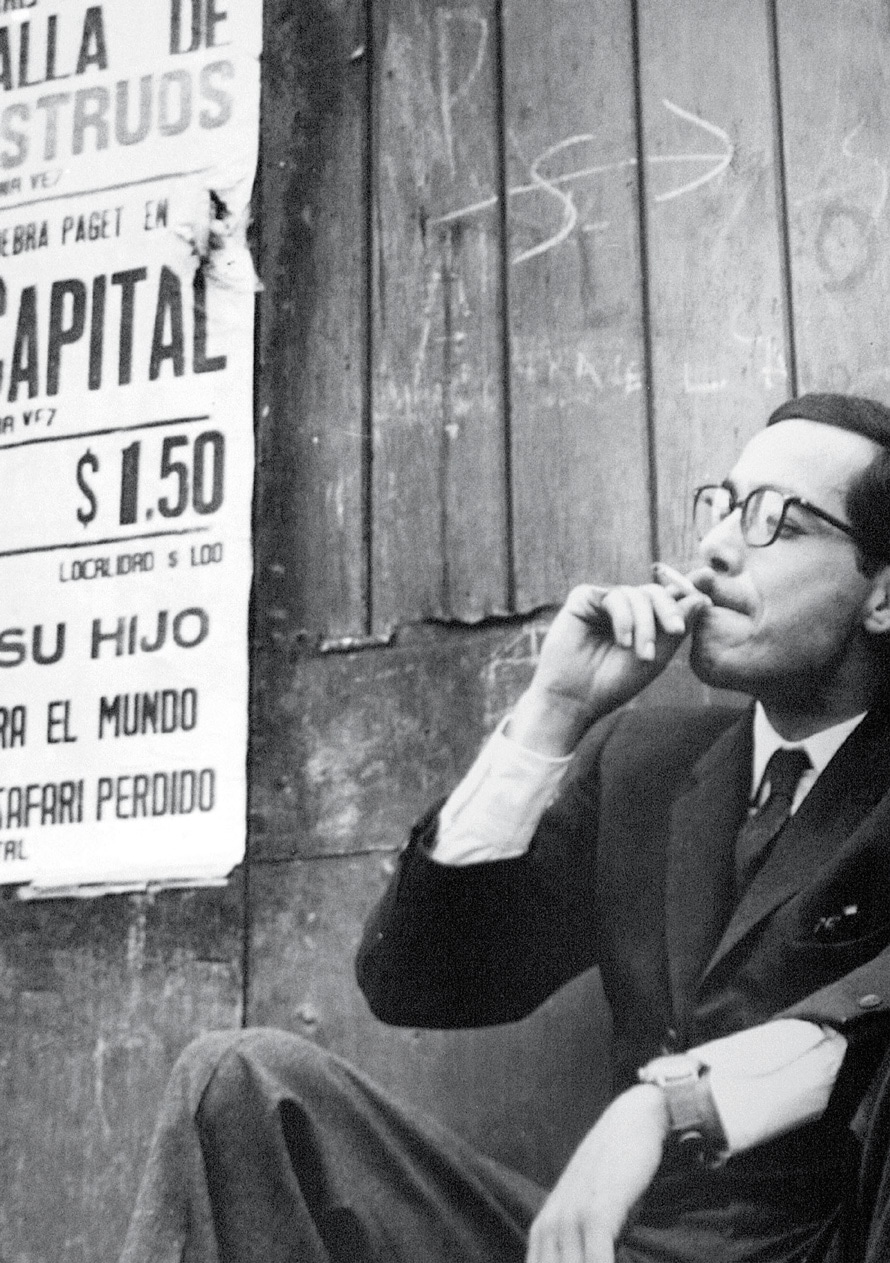

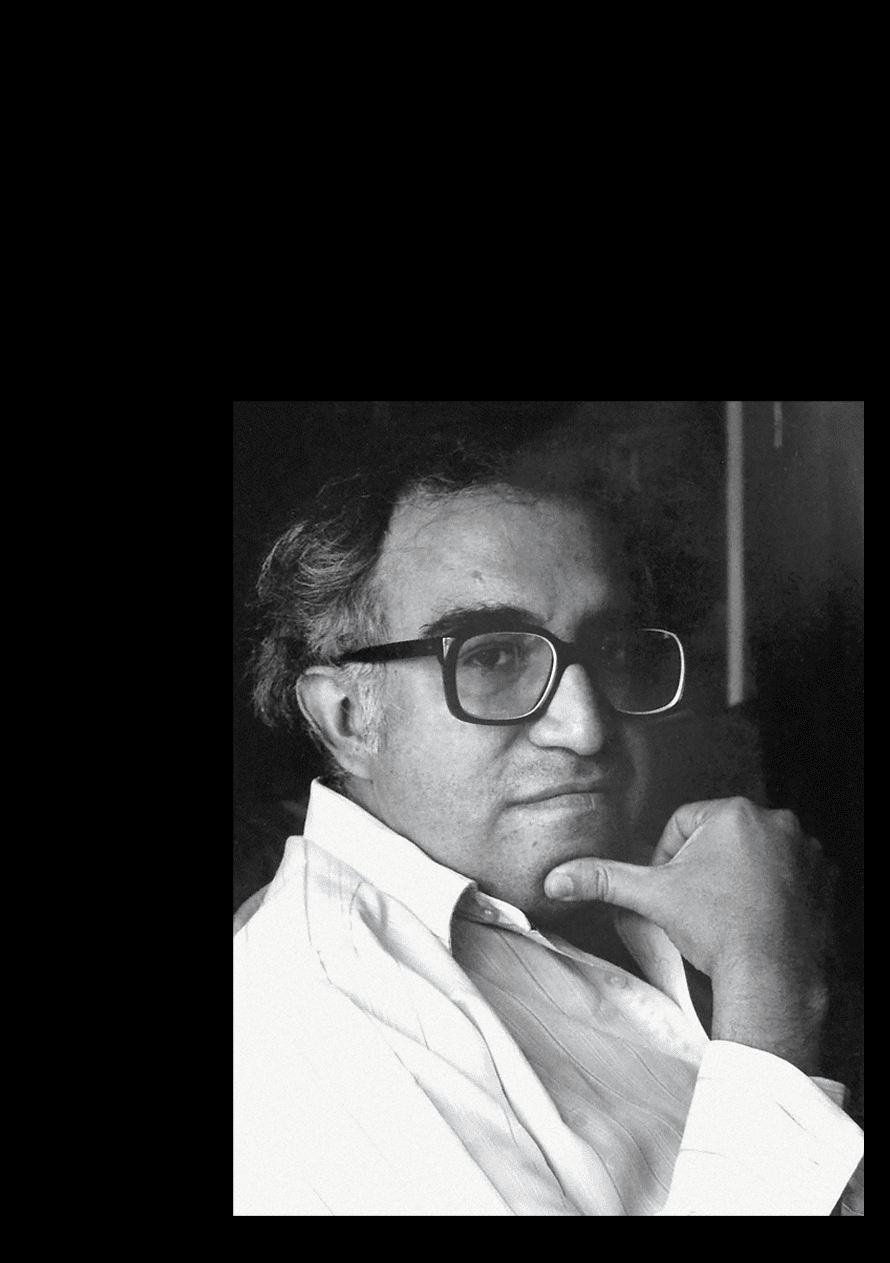

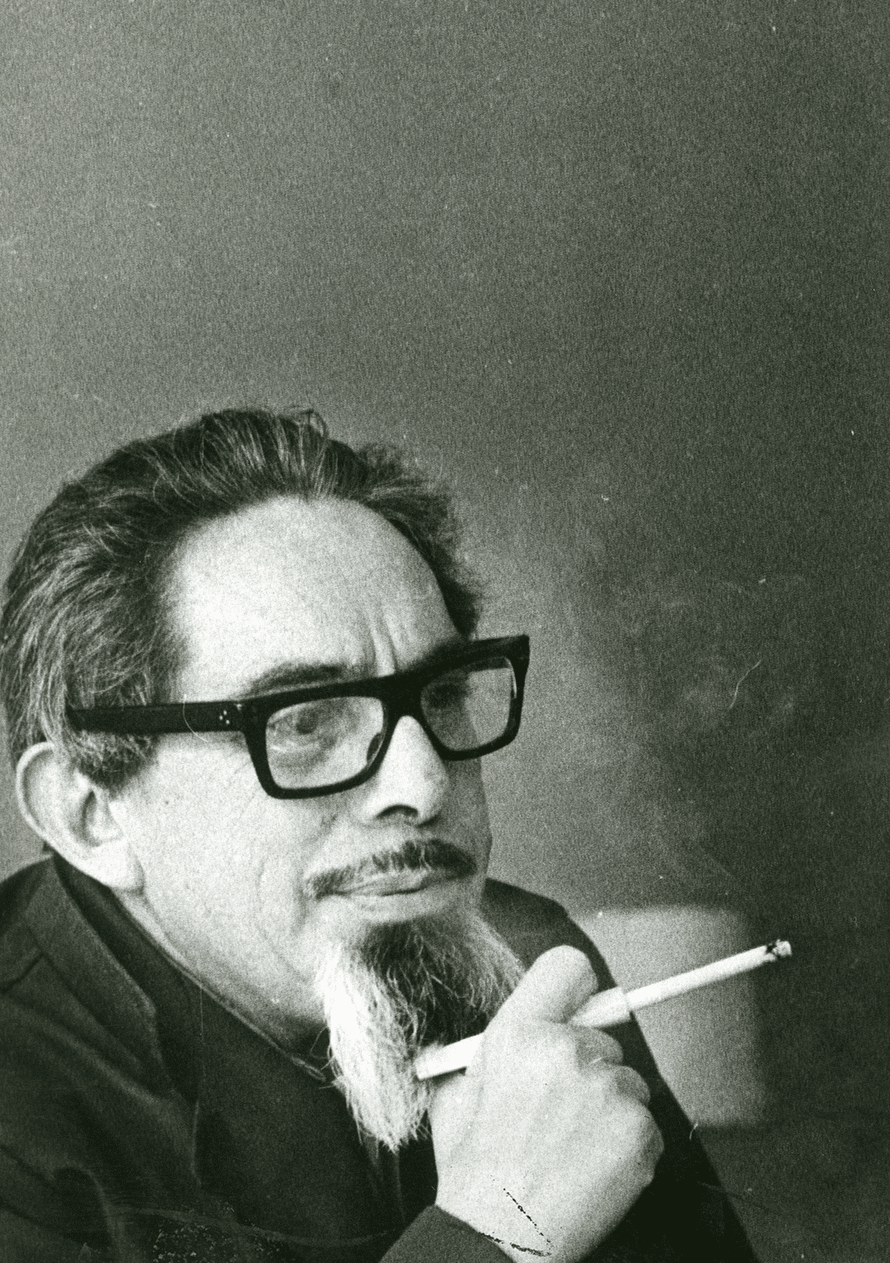

Legend has it that Juan José Arreola (1918-2001) was born with the gift of gab. In his village, Zapotlán El Grande, Jalisco, he was famous for being a reciter who from an early age assumed his passion for language.

Because of the Cristero War, which closed schools run by churches, he had to abandon formal studies and self-taught himself. When he turned 17, he left Zapotlán to go to Mexico City where he studied theatre.

His book Varia invención, published in 1949, placed him in the scene of Mexican literature. This stylistic exercise combining prose and poetry in different voices caught the attention of writer Jorge Luis Borges, who asked to meet the author in one of his visits to Mexico.

According to the Colombian critic Fabio Jurado: “Borges was the first to acknowledge Juan José Arreola as the author who was already revolutionizing and innovating Latin American narrative. That link with Borges makes us perceive in Arreola a presence of universal literature”.4

To speak of Juan José Arreola is to encompass a universe that combined histrionism with the written word, play, wit, laughter, memory and tradition. He is an essential writer in the history of our country’s literature and a reference that left a mark in the world of cultural television, entertainment and dissemination of culture.

Rosario Castellanos (Mexico City, 1925-Tel Aviv, Israel, 1974) occupies a place among the most renowned Mexican writers, nationally and internationally. She was a pioneer of Latin American feminism cultivating all literary genres brilliantly: she wrote eleven poetry collections, three novels, plays, stories, essays and journalistic texts.

Her work was always strongly imbued with an autobiographical tinge, and stood out for her sharp criticism towards a society defined by social disadvantages.

During her childhood in Chiapas, she witnessed the vulnerability of indigenous groups and in her role as a woman writer, diplomat, professor and mother she faced the difficulties of standing out in a field governed by men.

A woman ahead of her own time, she stood up against the marginalization of women, the objectification of the female body, the reduced number of women in professions considered exclusive to men, the wage gap, the mystification of motherhood and the prejudices that weigh against Mexican women.

Denunciation against discrimination marked the essence of her narrative, which is illustrated in El eterno femenino, Balún Canán (Chiapas Award, 1958), Ciudad Real (Xavier Villaurrutia Award, 1960), The Book of Lamentations, Álbum de familia or Poesía no eres tú. She was honored with the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Award (1962), the Carlos Trouyet Prize for Literature (1967), and the Elías Sourasky Prize (1972).

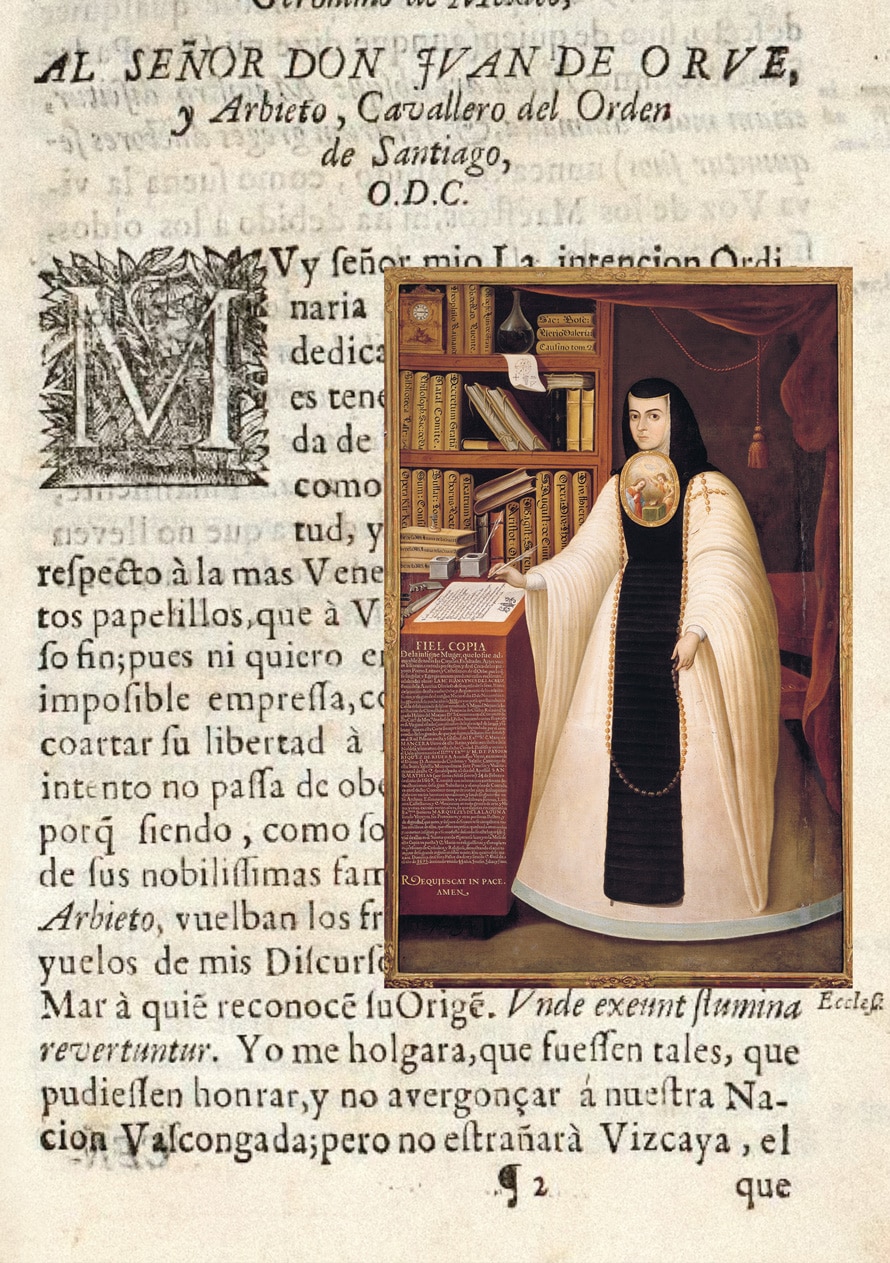

Let it be inscribed here the day, month, and year of my death. I beseech […] my beloved sisters, the nuns here now and those who shall be, commend me to God: I, who have been and remain, the worst that has ever been. I beg their pardon […]. I, the worst woman in the world.18

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana (1648-1695) was born in the Hacienda of San Miguel Nepantla, in the State of Mexico. Erudite, writer and nun narrates in her letter Reply to the Most Illustrious Sor Philotea de la Cruz how she learned to read and write at age three; how at five years old she expressed her desire to go to University and wrote her first poem when she was eight years old.

Considered the Tenth Muse, she was the first great poet of Latin America, but her work was not limited to lyrical poetry, she also explored prose and essay, and wrote several plays. UNESCO declared her literary heritage as Memory of the World.

In addition to being one of the most important writers of the 17th century, she distinguished herself as an advocate of women's rights to access intellectuality. Entering a convent was her only option in order to dedicate herself to writing, so with the conviction that the mind should be filled with ideas rather than beautiful things, she donned the habit in order to stand up for her right to think.

Novelist, poet, essayist, translator and literary critic, Salvador Elizondo (Mexico City, 1932-2006) is one of the most original and innovative writers of his generation. Writer Daniel Sada describes him as “the most unclassifiable author of Mexican narrative”.

In 1965 he received the Xavier Villaurrutia Award for Farabeuf, the foundation stone of one of the most ambitious literary projects of Mexican literature. It revealed a style that took formal experiments to the limit in order to delve into linguistic and philosophical issues, interior life and the construction of reality.

This first novel was followed by The Secret Crypt (1968), El retrato de Zoe y otras mentiras (1969), and El grafógrafo (1972), among others, in addition to Diarios and over one hundred notebooks where he included texts, drawings, photographs, jokes and reflections.

In 1976 he became a member of the Mexican Academy of Language and El Colegio Nacional, where he was a founding member. He also received support from the Ford Foundation to study in New York and San Francisco, as well as the Guggenheim Foundation (1968-1969). In 1990 he received the National Prize for Literature.

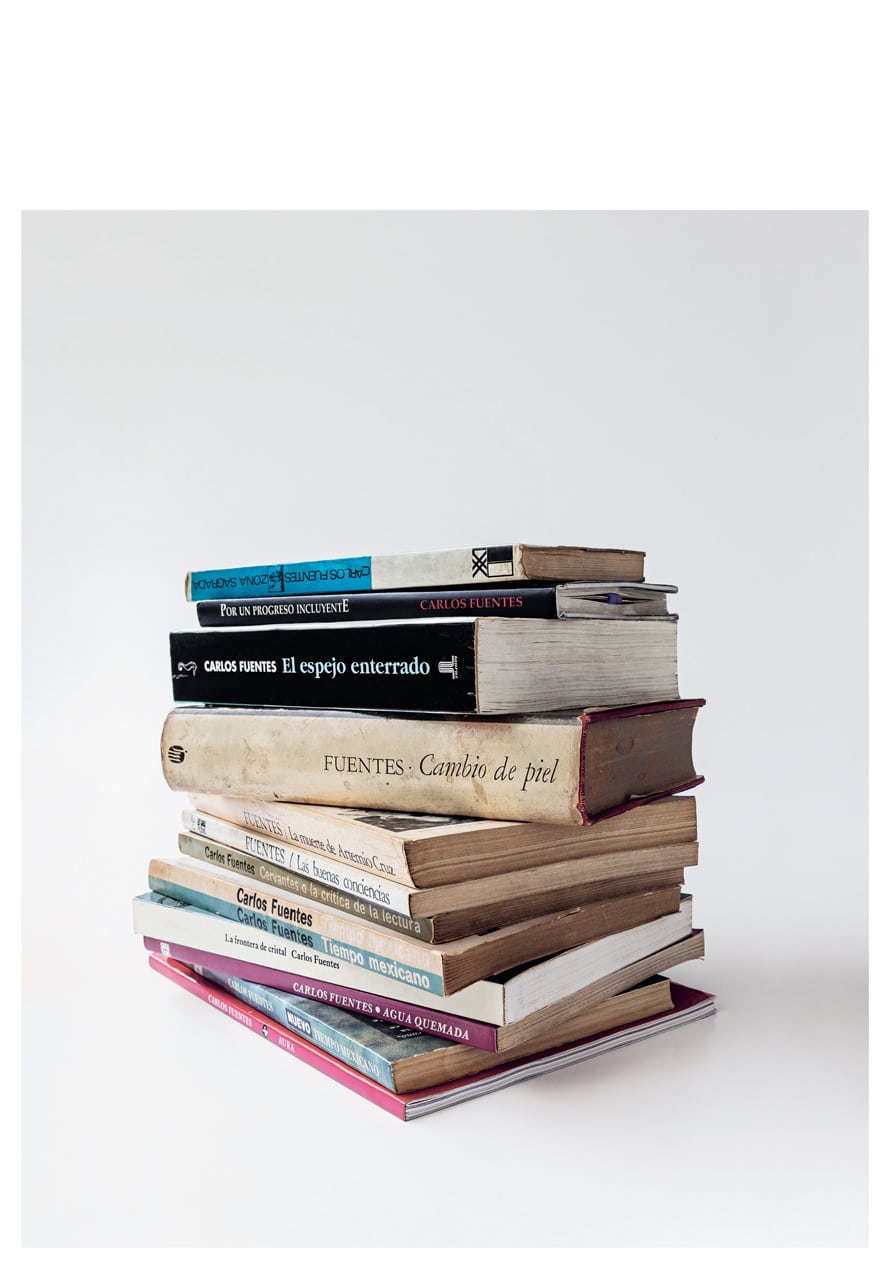

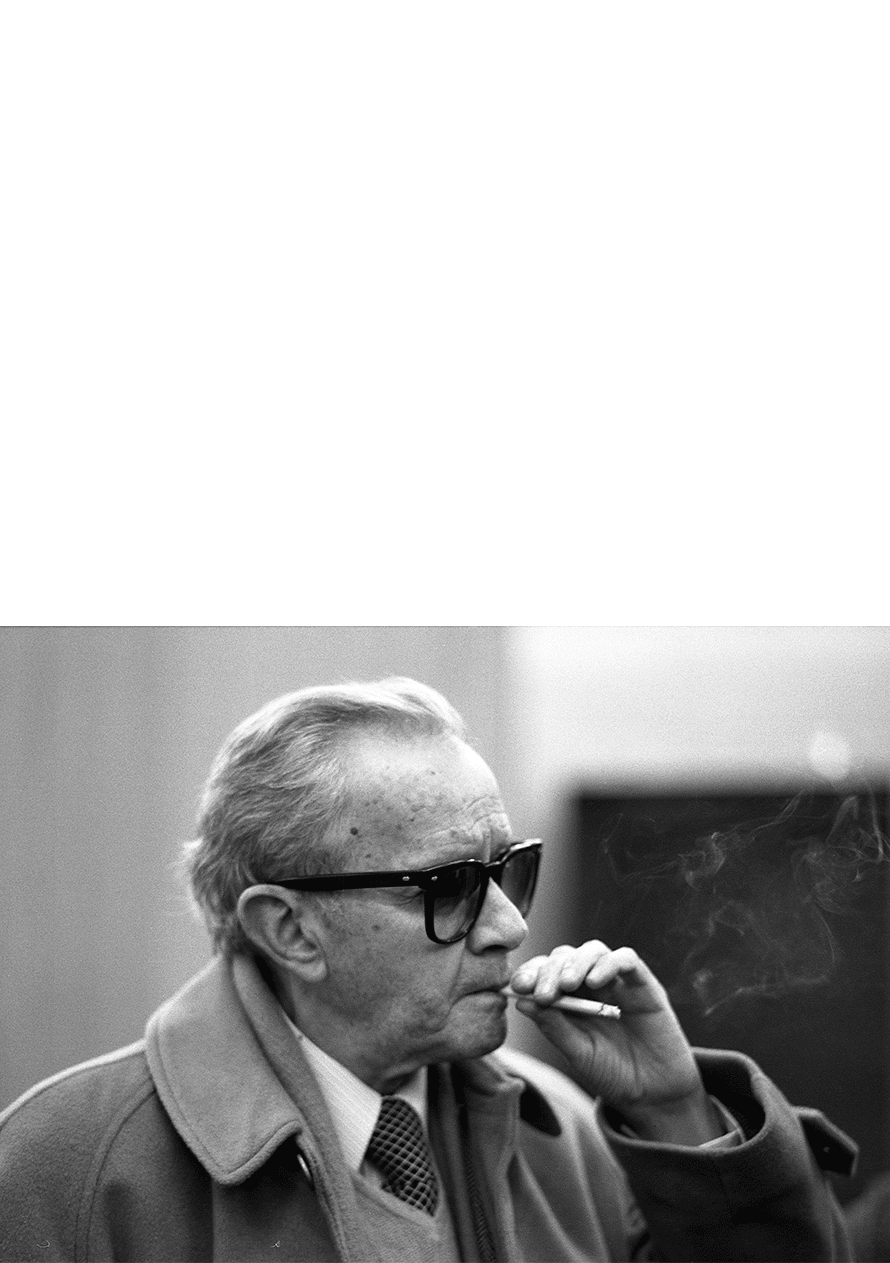

Carlos Fuentes (1928-2012) was a writer and diplomat. He is one of the main representatives of the Latin American Boom, a literary movement that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, and included among its ranks writers such as Julio Cortázar, Mario Vargas Llosa and Gabriel García Márquez.

This explosion of young narrative challenged the established conventions of the Latin American literature of the time and caused the flowering of an aesthetic sense of its own, with a free use of language and subject, which responded to the political and social influence of current affairs in the country of each of its representatives.

In this context, Fuentes was well received since the publication of his first novel, Where the Air is Clear (1958); later, Aura and The Death of Artemio Cruz (1962) consolidated as two of the most important novels in Mexican literature. He is the author of twenty novels and an important number of essays, short stories, plays and screenplays.

Awards were a constant in his life, due to the brilliant development of his career. In addition to several medals and decorations, he obtained over twenty honorary doctoral degrees granted by several universities —among them Harvard and the National Autonomous University of Mexico—, in addition to receiving the National Prize for Science and Arts in Linguistics and Literature (Mexico, 1984), the Miguel de Cervantes Prize (Spain, 1987), the Prince of Asturias Literature Prize (Spain, 1994), and the Grizane Cavour International Prize (1994), among many others.

It is here [in Mexico], where I have written my books, where I have raised my sons, and where I have planted my trees.21

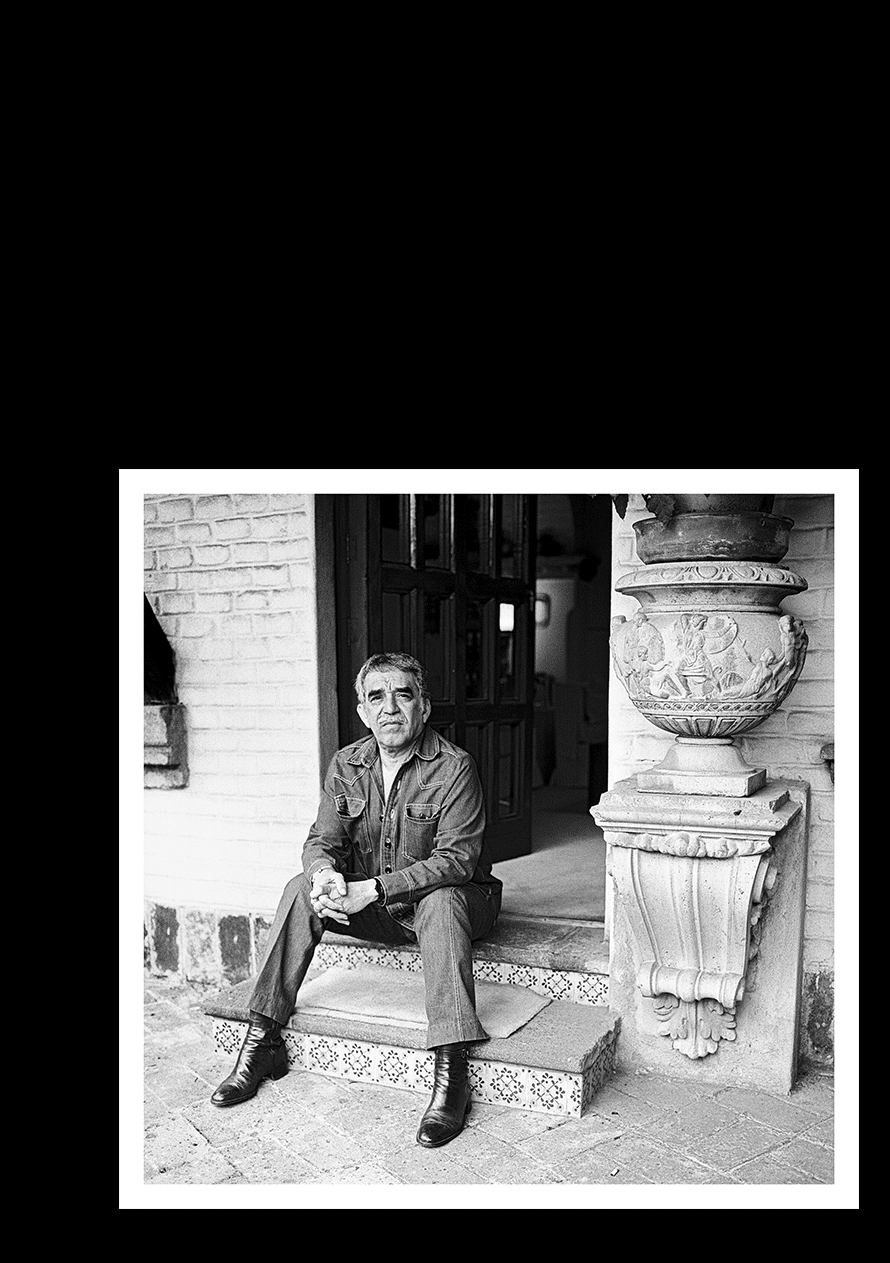

Gabriel García Márquez

Although he was born in Colombia, Gabriel García Márquez (1927-2014) considered Mexico as his “other distinct homeland”. Exiled for political reasons and with twenty dollars in his pocket, he moved to Mexico City in 1961 with his family. Among the streets of this “luciferian city” he found shelter and worked as a journalist, advertising editor, editor and screenwriter.

While driving to Acapulco, the first sentence of One Hundred Years of Solitude came to his mind. “It was so mature”, he recalled, “that I could have dictated the first chapter, word by word, to a typist, right there on the highway to Cuernavaca”.22

Gabo, as he was known, hurried the family vacation to return to home, quit his jobs and sat down to write for eighteen months, while Mercedes, his wife, supported the household. This is how the novel that gave him universal fame and profiled him to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982 was born. That same year, the Mexican government distinguished him with the Order of the Aztec Eagle.

The father of magical realism died at his home in the Pedregal neighborhood and was seen off with a tribute at the Fine Arts Palace, an honor that only the most illustrious Mexicans receive.

Elena Garro (Puebla, Puebla, 1916-Cuernavaca, Morelos, 1998) defined herself as “the restless particle” and so she was: dancer, choreographer, playwright, poet, narrator, screenwriter, journalist, activist... She was never still and she left in her wake a trail of words, which compose one of the most important works of Hispanic American literature.

She is considered the second most important woman in Mexican literature after Sor Juana; precursor of magical realism, which she perfected in her novel Recollections of Things to Come, published in 1963, but written and read a decade earlier in literary circles to which authors such as Gabriel García Márquez belonged.

Her narrative, object of many analyzes and studies, introduced new ways of conceiving time within the story, and her plays such as Felipe Ángeles, Un hogar sólido or El árbol, are considered renovated pieces of Mexican dramaturgy. In journalism she found a potent weapon used in the defense of leader Rubén Jaramillo and the peasant cause.

Unfortunately, her work was overshadowed for a long time by slander, persecution and exile, after an agitated 1968 during which she was openly against the authoritarian and critical regime in opposition to the comfort of intellectual circles.

There are many creators —from all periods and artistic disciplines— whose names have been inextricably linked to one of his works, to the iconic piece of his legacy. That is the case of José Gorostiza (Villahermosa, Tabasco, 1901-Mexico City, 1973) and his inexhaustible poem Death Without End, considered an essential composition of literature in Castilian language.

Death Without End was published in 1939 and had an immediate impact on the world of literature, where it was described as “one of the greatest achievements of contemporary poetry”. It is an extensive work, consisting of ten parts where he pours the distress of the individual being in a song of philosophical searches, dedicated equally to existence and to destruction. Its complexity, which continues to be the subject of extensive studies, lies in the fact that it functions at multiple levels, which the poet elaborated with the idea, he said, of “doing something as someone constructing a building, with the criteria of an architect or as the composer who intends to create a symphony”.

Gorostiza belongs to the generation of the Contemporaries, a legion of poets and critics essential for the development of Mexican literature in the 20th century, an example of the “New Mexicans” convinced that Mexicanness was not at odds with universality.

Martín Luis Guzmán (Chihuahua, Chihuahua, 1887-Mexico City, 1976), witness and participant of the Revolution, occupies an important place among chroniclers of the transformation of Mexico during the 20th century. His work influenced the construction of historical narrative and development of contemporary national literature.

Member of Pancho Villa’s troops, politician, journalist and public official, his nature was that of a man of action who only entered into literature when exile took him away from his other tasks.

During his exile in the United States and Spain, he wrote La querella de México (1915) —which spearheaded other texts that question the condition of Mexicans, whose pinnacle is The Labyrinth of Solitude by Octavio Paz—, The Eagle and the Serpent (1928), The Shadow of the Strongman /(1929), and Memoirs of Pancho Villa (1951).

According to writer Juan Villoro, The Shadow of the Strongman is an “inexhaustible and tragically current”25 novel, considered by Federico Campbell as the masterpiece on the criminalization of the Mexican state.

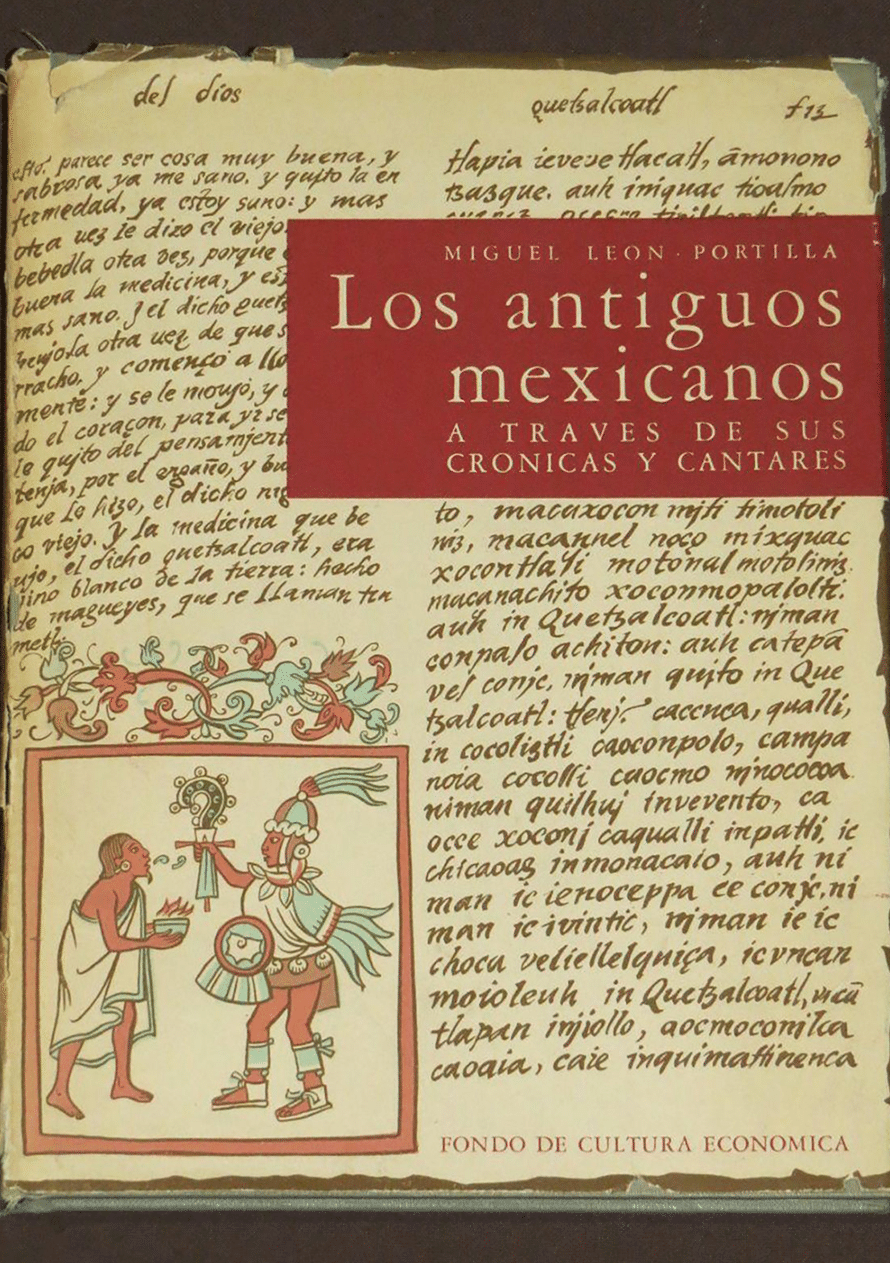

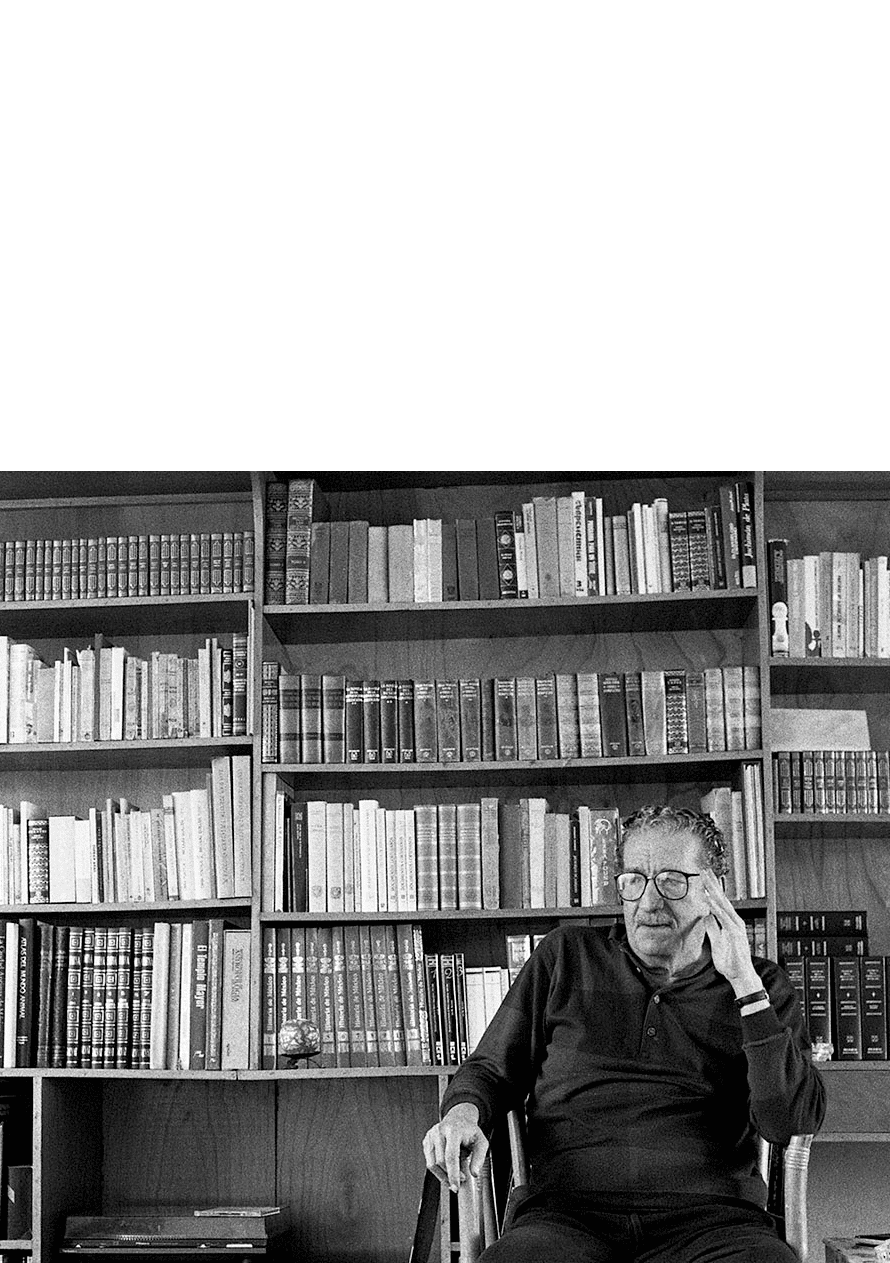

Miguel León-Portilla (Mexico City, 1926) is much more than a philosopher, philologist, historian, researcher, professor and expert on Nahuatl thought and literature. He is a scholar of the indigenous soul, a discoverer and disseminator of the true richness of Mesoamerican peoples.

Heir to the passion and knowledge of teachers such as Manuel Gamio and Ángel María Garibay, León-Portilla has dedicated his life to rescue the memory, voice and poetry of living native peoples. To undertake this tireless work in defense of the prehispanic world, he committed himself, from a very young age, to the study of Nahuatl and indigenous culture.

Since then, he has held countless chairs, in addition to writing hundreds of articles and around forty books that include: La filosofía náhuatl estudiada en sus fuentes (1956), Los antiguos mexicanos a través de sus crónicas y cantares (1961), Time and Reality in the Thought of the Maya (1968) and The Broken Spears (1959), his most important work. This essential book —translated into 26 languages— rescues chronicles of events of the conquest, written in Nahuatl by natives, which had to wait centuries to come to light.

Apart from an endless number of awards received during his career, Miguel León-Portilla was honored with a national tribute in 2019 given his invaluable contributions to the knowledge of the history of our country.

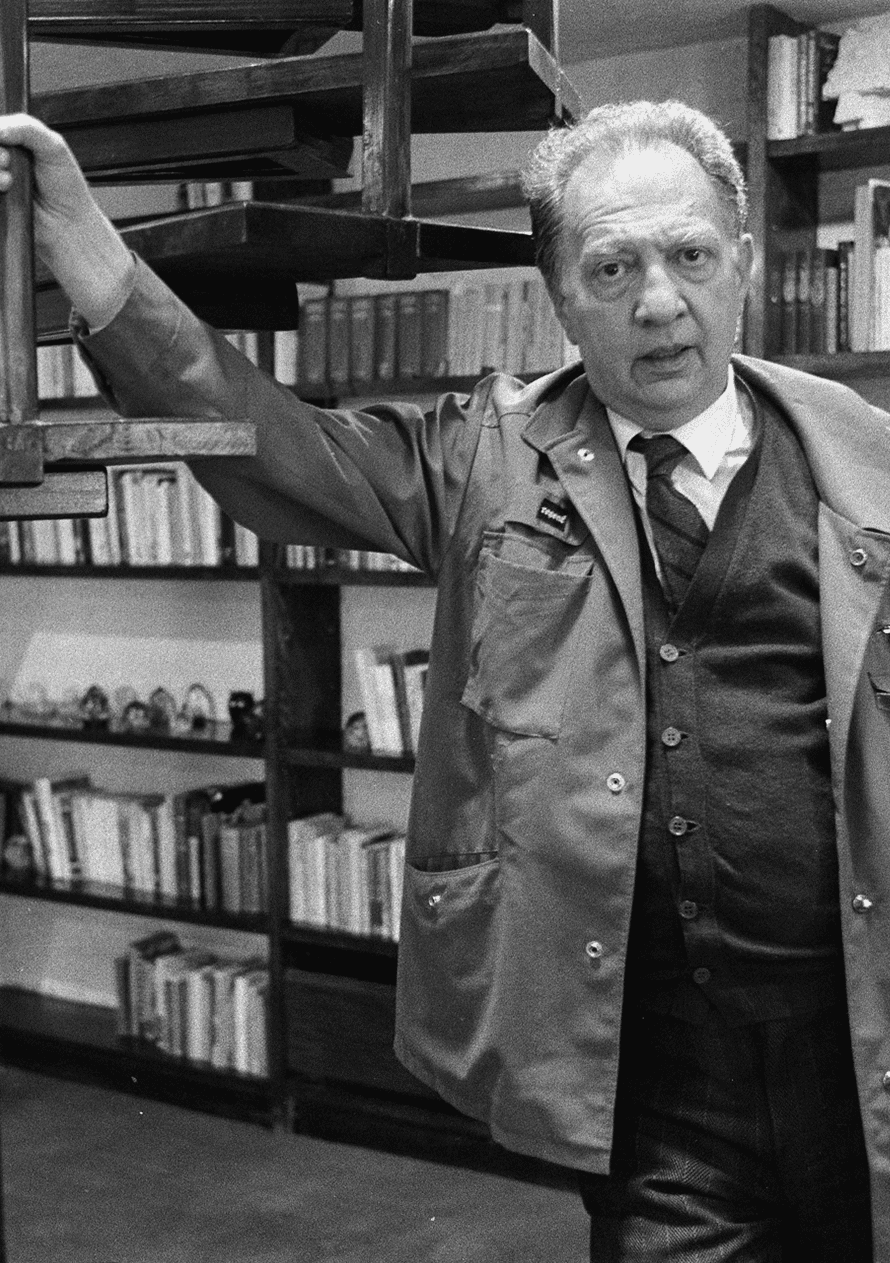

Carlos Monsiváis (Mexico City, 1938–2010) was one of the most influential writers in Latin America. He managed to forge an endless production of millions of words, in thousands of texts that blurred the border between chronicle, journalism and literature, and through which he deciphered Mexican culture.

“Monsi”, as he was known, was essentially a collector. Endowed with a prodigious memory, he could recite entire verses of the Bible, poems, historical data, jokes and all kinds of anecdotes —his own or somebody else’s— which he treasured as well as his collection of books, documents, toys, photographs, cartoons, art and objects that add up to over twenty thousand pieces, now protected in the Museo del Estanquillo.

The “Favorite Son” of the Portales neighborhood in Mexico City, cleverly described city happenings through varied resources, from critical historical analysis to ironic metaphors, praise and mockery, becoming an essential figure in national culture.

His chronicles are part of the education of Mexicans and have shed light on the meaning of Mexicanness. It is said that the city loved him so much that it granted him the gift of ubiquity, so he could see and be seen at the same time in several places. His work is grouped into books such as Días de guardar (1970) and Escenas de pudor y liviandad (1981-1988).

Fernando del Paso (Mexico City, 1935–Guadalajara, Jalisco, 2018) was a peculiar man who knew how to travel and move brilliantly among several worlds. He masterfully practiced narrative, but also poetry, painting, journalism, advertising and even gastronomy.

A lover of literature, colors and humor, since childhood he took advantage of his ambidextrous ability —“ambisinister”, as he called it— to explore his two great passions: drawing and writing. He could literally write with his left hand and simultaneously draw with the right one.

He also moved from the field of intellectual literature to the world of best sellers. While Palinuro de México (1977), his made-up autobiography, earned the reputation of a work reserved for cult readers, News from the Empire (1987) burst in as an immediate sales success that reached all kinds of audiences, and years later was chosen in a survey among a plethora of writers as the most important Mexican novel in three decades.

Both novels he wrote completely by hand, in his long stay between London and Paris —thanks to the support of the Guggenheim Fellowship. At that time, he also served as a radio program producer, writer and broadcaster at the BBC and Radio France. In 2015 he was awarded the Cervantes Prize in recognition of “his contribution to the development of the novel, combining tradition and modernity as Cervantes did in his time”.

In December 1990, the poet, narrator, essayist, translator, editor and great promoter of Mexican literature, Octavio Paz (Mexico City 1914–1998) received the Nobel Prize for Literature that the Swedish Academy awarded him in recognition for his “impassioned writing with wide horizons, characterized by sensuous intelligence and humanistic integrity”.

The body of his work is full of essential essays for contemporary culture. In The Labyrinth of Solitude (1950) he dissected the psychological construction of Mexican people; in The Bow and the Lyre (1956) he tried to decipher the poetic phenomenon; and in The Double Flame (1993) he explored the feeling of love and eroticism, in addition to many other texts dealing with art, society, history and international politics. But, for Paz, everything flowed back into poetry and that is where the axis of his literature and his raison d’être lie. Libertad bajo palabra (1960) brings together his poems written between 1935 and 1957 and covers topics such as loneliness, love, death, solidarity and social contradictions.

The poet who said that “the Nobel Prize is not a passport to immortality”, was distinguished with many awards, but above all recognitions, his legacy is incalculable and permanent. His work made him one of the most lucid Mexicans of the second half of the 20th century, a reference of universal thought, literature and poetry.

Sergio Pitol’s (Puebla, Puebla 1933–Jalapa, Veracruz 2018) literary calling is vitally attached to that of a traveler in transit. His wandering nature took him to many countries as a professor, translator and diplomat or simply as an adventurer in search of universes to narrate.

Every certain mileage he found an excuse to settle in places as different as Beijing or Warsaw, and turn to the knowledge of the local language or the work of a writer, which he later translated into Spanish.

His work as a translator has been fundamental for the knowledge of essential authors such as Henry James, Robert Graves, Anton Chekhov, Witold Gombrowicz or Vladimir Nabokov. The translation of hundreds of books from Polish, English, Italian and French is owed to Pitol.

The journey and interpretation —of languages, worlds, facts or characters—permeated his narrative work and can be appreciated in his stories and in his Trilogy of Memory, consisting of The Art of Flight (1996), The Journey (2000) and The Magician of Vienna (2005).

In 2005, his career was acknowledged with the Cervantes Prize and in 2006 the Instituto Cervantes’ library in Sofia, Bulgaria was inaugurated in his honor.

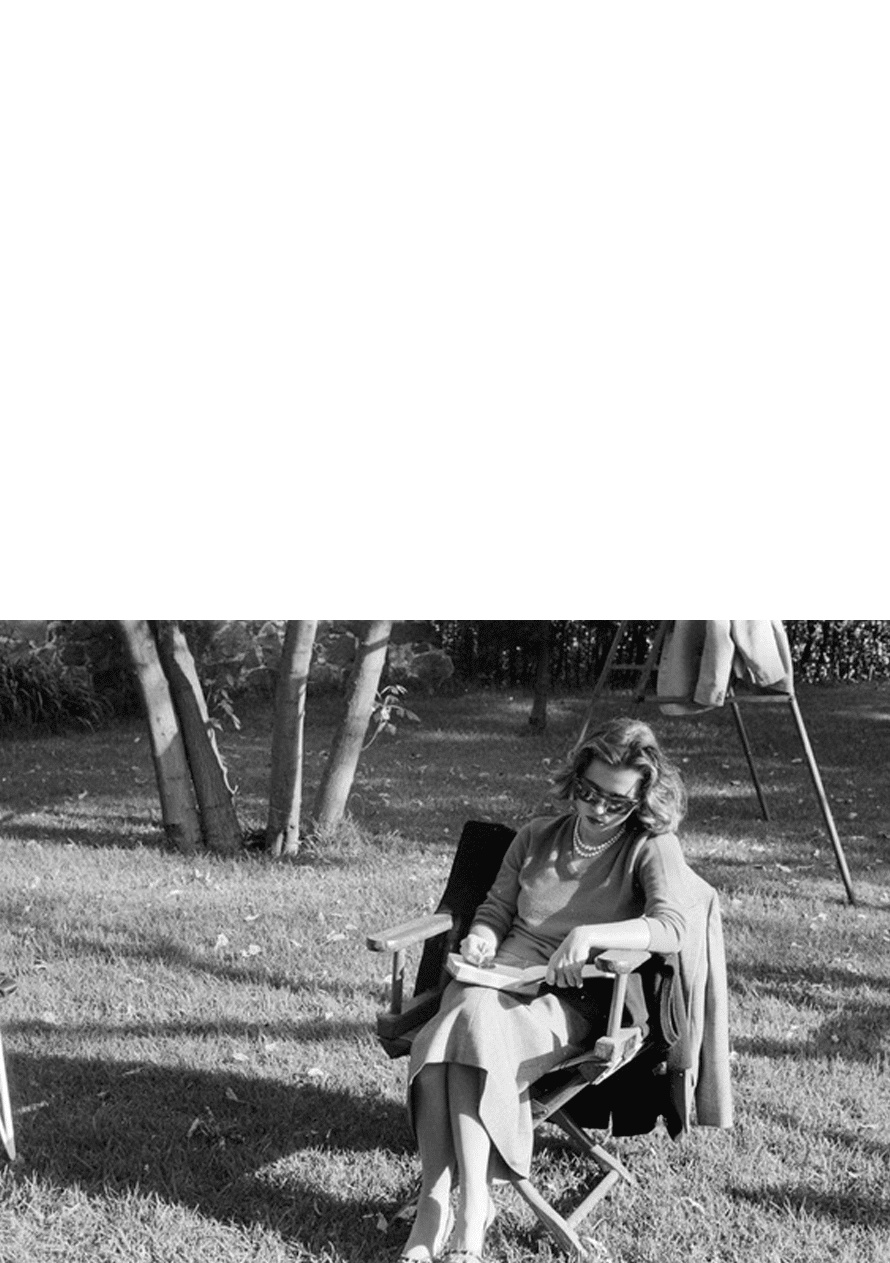

Elena Poniatowska (1932) was born in Paris, France. Her mother, Dolores Amor, born into a Porfirian family exiled in France after the Revolution, married the also exiled Prince Jean Poniatowski, heir to the Polish crown, so Elena was born with the title of Princess of Poland, which —she says— she cared very little about. When World War II broke out, the family returned to Mexico.

At age 18 and by then proven to be “more Mexican than mole”, with a mixture of curiosity and boldness, she began to interview great artists to research their creative process and the social sense of their work. Thus began her career as a journalist that is known for reflecting the feelings of ordinary people.

In 1968 newspaper Novedades refused to publish her report on the October 2nd massacre. That material, enriched, became the book Massacre in Mexico (1971), for which she was awarded the Xavier Villaurrutia Prize, an award she rejected because she considers that the date should be officially commemorated as national mourning.

She has combined her journalistic work with literature, delving in almost all genres: novel, short story, poetry, essay, chronicle, theater and texts for children. In her work, stories about women are notable, including: Tinísima (1991) —on the life of Italian photographer Tina Modotti—, Las soldaderas (1999) or Leonora (2014) —a portrait of Leonora Carrington.

In 2013, she was the first woman to receivethe Cervantes Prize.

It is in few writers that we find such a close and torn relationship between their life and their work as in José Revueltas (Durango, Durango, 1914–Mexico City, 1976). His work truthfully evokes his last name [which in Spanish means in a turmoil]: he was a turbulent man, dissident of the Mexican political system in all its aspect, including those of the left wing, since he did not see in Marxism a faith, but an instrument of social liberation.

His irreducible political militancy led him to be imprisoned on several occasions, both in Lecumberri and on the Islas Marías. These seclusions resulted in his books Los muros del agua (1941) and The Hole (1969), which are integrated into the body of a work consisting of various chronicles, novels and stories that delve into cruelty, impotence and human misery.

He was also a prolific film scriptwriter, a journalist, playwright and, it is said, an extraordinary conversationalist capable of “drinking to sobriety”. His works have been translated into English, Italian, Hungarian, French, German and Polish.

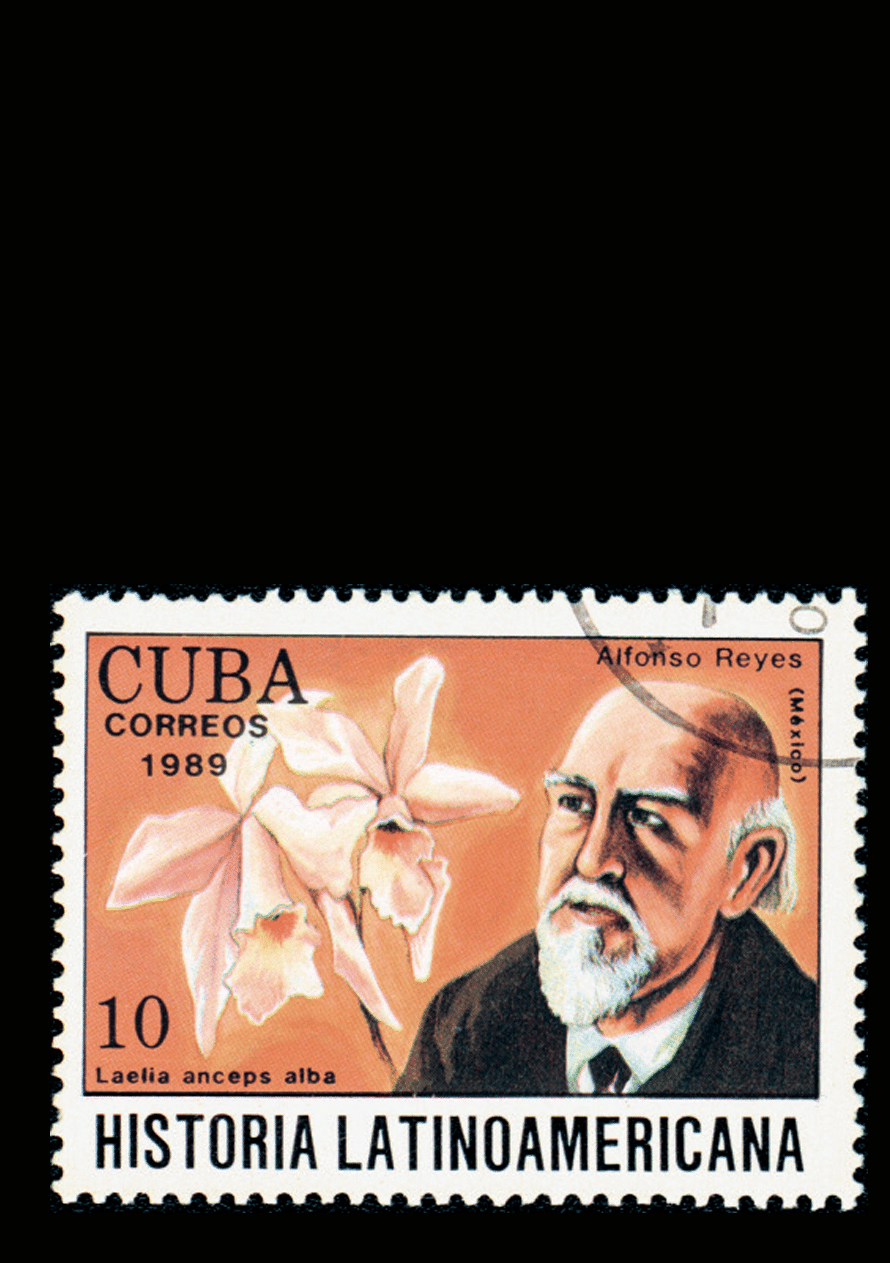

Let us be generously universal so as to be profitably national.42

Alfonso Reyes

Considered a polymath, Alfonso Reyes (Monterrey, Nuevo León, 1889-Mexico City, 1959) was a lawyer, essayist, narrator, poet, playwright, translator, teacher and diplomat. Borges named him “the greatest prose writer in Spanish of any period”43 and he is considered —along with José Vasconcelos— as one of the two greatest Mexican intellectuals of the first half of the 20th century.

During his years as a diplomat, he rose as the ambassador of Mexican literature, in his tenure in Spain, France, Argentina and Brazil, where he was known as “The Universal Monterrey-born”.

In 1939 he returned to his homeland to preside over El Colegio de México, a fact that marked the beginning of a work that consolidated him as the great civilizer of the country, which at that time was defined by nationalism —the revolutionary novel and the mural movement prevailed—, with a renewed stability that favored the creation of institutions over which Reyes had a fundamental influence to build modern Mexico.

He advised on the dangers of reducing Mexican culture to exclusive nationalism and, from the institutions, he passed on his passion for universal literature and cleared the culture scene to open its borders.

He received plenty of recognition for his career, including the National Prize in Literature in 1945. That year he was nominated for the first time for the Nobel Prize in Literature, a nomination he would receive four more times.

Juan Rulfo is the only Mexican novelist who has given us an image —not a description— of our landscape. His intuitions and personal obsessions have been embodied in stone, dust, the pepper tree. His vision of this world is, actually, a vision of another world.47

Octavio Paz

Originally from Sayula, Jalisco, Juan Rulfo (1917–1986) is known as “the creator of national sentiments”, a writer who only had to publish two books to register his name among the most important in contemporary literature.

In 1953 he published The Burning Plain and Other Stories. Two years later he put an end to the traditional rural novel with Pedro Páramo, by creating a narrative of meticulous, almost poetic language, which combined reality and fantasy in a setting that became the notion of the Mexican countryside that prevails in the collective imaginary. “It adds up to no more than 300 pages”, Gabriel García Márquez once said, “but I believe they are as everlasting, as the pages that have come down to us from Sophocles”.48

“I came to Comala because I was told that my father, a certain Pedro Páramo, lived here” is the best-known novel opening sentence referenced in the world. By 1986, the year of the death of its creator, it had been translated into 60 languages and its print run in Spanish had reached millions.

The most important tribute is that people read me, that my books become useful. Once, a boy told me that my poetry had accompanied him for three years on the roof of his house while studying law. When he graduated, he thanked me for that time. 49

Jaime Sabines

In the sphere of Mexican poetry, the figure of Chiapas born Jaime Sabines (1926–1999) stands out as one of the poets most appreciated by a multitude of readers that chronicler Carlos Monsiváis once named as “The brotherhood of those that love”.

The vast scope of the work of the creator of “The Lovers” —his reference poem— resides in his human quality. With the use of a natural and unrestricted language his poetry names everyday things and events that cling to the memory of those who quote his verses with the ease of those who talk about their lives.

Distanced from intellectual trends and groups, Sabines left a legacy that remains alive: Some-thing About the Death of Major Sabines (1962) and Tarumba (1979), are his most notable books, and together with anthologies such as Recuento de poemas, they are constantly reissued and studied in countries like Germany, Bulgaria, United States, Cuba, Canada, Chile, France and Spain. His work has been translated into about twenty languages, including Chinese, Russian, Arabic and Italian.

The poetry of Tomás accompanied us in loving bliss but also in heartbreak, abandonment and solitude. For those dark stretches of life, Cantata a solas is […] almost “a survival manual”.51

Enrique Krauze

At the age of thirteen, Tomás Segovia (1927–2011) disembarked in Mexico and found in this country a solidary refuge, like so many exiles from his native Spain, facing a civil war at the time. In Mexico he lived the fullness of his teenage years and he studied until he became one of the great poets of the Spanish language.

His work —which earned him the Guggenheim Fellowship (1950), the Extremadura Creation Award (2007), and the Federico García Lorca International Poetry Prize (2008)— delved deeply into the mythical, the eternal mystery of love, and in an “eager of body” eroticism, of high literary flights.

Among his main works are La Luz provisional (1950), El sol y su eco (1960), Anagnórisis (1967) —long poem of complex structure, emblem of his bibliography—, Cantata a solas (1985) and La casa del nómada (1994).

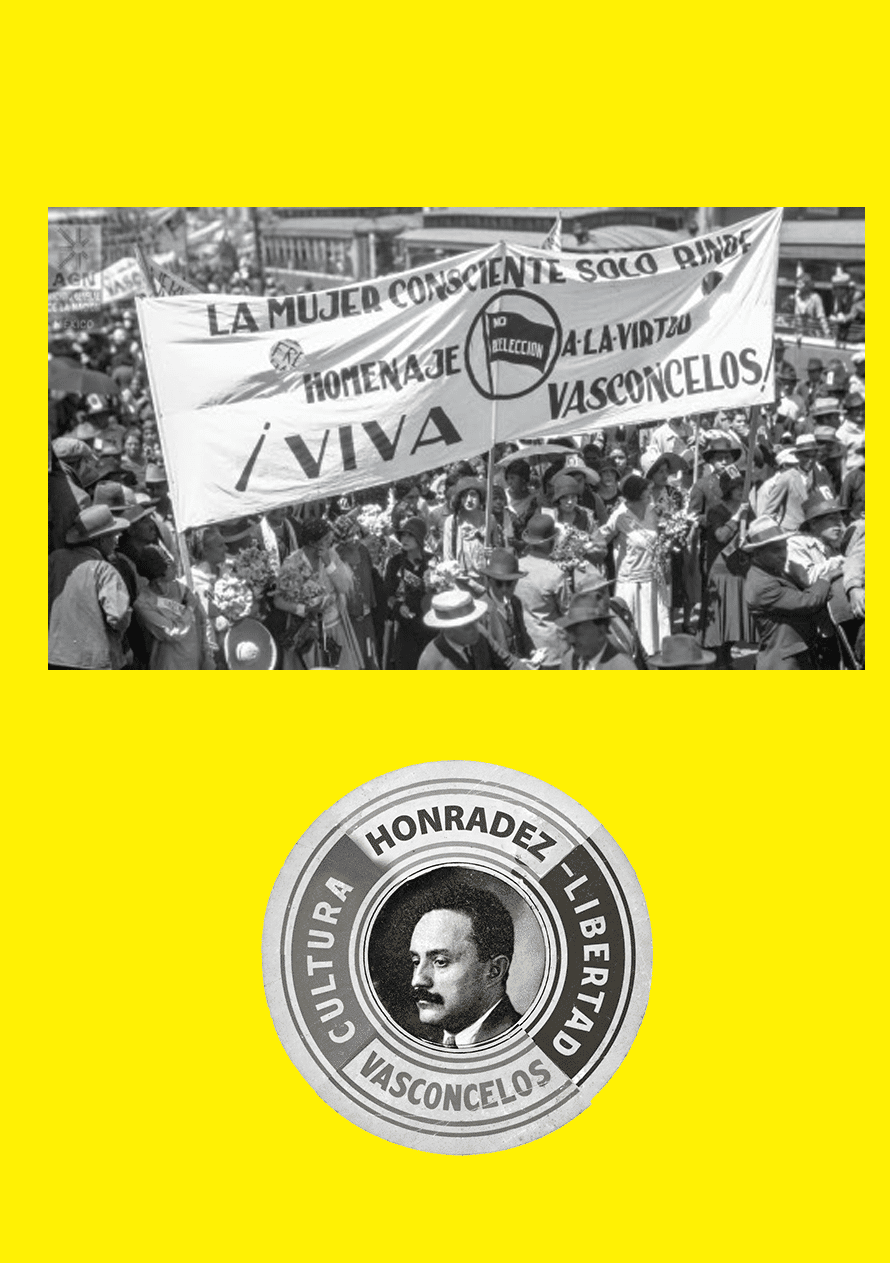

Originally from Oaxaca, José Vasconcelos (1882–1959) was called none other than “Teacher of America’s Youth”. Interested in political life —permanently critical, opposed to the government— he stood out as an academic and philosopher, and left an extensive work recognized with the highest literary value.

His creation includes collected letters, criticism and fiction on a variety of topics, including ethics, aesthetics and metaphysics, highlighting the autobiographical series that begins with his famous A Mexican Ulysses (1935) and the lucid criticism of racism contained in The Cosmic Race (1925).

However, the most famous aspect —perhaps the most important— of his legacy is what gives him a special place in history as an educator. He was our first Minister of Education and, as such, he undertook a campaign for popular education. He founded networks of libraries, normal schools and La Casa del Pueblo schools. He integrated and launched a collection of universal literature in a massive edition —with the works of Homer, Tagore, Goethe, Dante, among other masters of literature— that reached the entire country. He opened official buildings to the muralists in order to make them accessible to the people. He was a member of El Colegio Nacional and the Mexican Academy of Language. In addition, he was Dean of the National University. He can truly be considered an apostle of education.